Dissertation June 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libations: the Sexy Side of Cognac

Love & Libations: The Sexy Side of Cognac B y: Yolanda Shoshana During Valentine’s Day season most people focus on Champagne. That’s totally understandable because it’s one sexy wine. I want to encourage you to try something other than sparkling wine. How about adding Cognac into your libation rotation? It’s that time of year, February, also known as the month of love. Though at Cupid’s Pulse we bring the love year-round. Cognac is produced in a very charming city of the same name in France. French is the language of lovers so think of it as the spirit of “love in a bottle”. For so long people have thought of Cognac as an older man’s drink, but it couldn’t be further from the truth. The spirit has a vibrant history of being the libation of choice by kings, queens, and aristocrats. Now, most people think of rappers when they see Cognac. It’s true than many famous singers/rappers love Cognac. However, it’s also enjoyed by men and women around the world, especially in Japan and the US. Besides being known for luxury, it’s rather seductive. It’s easy to find it as an ingredient in cocktails at fancy hotel bars and even dive bars have gotten into serving classy Cognac drinks. People have caught on to how delightful and versatile Cognac can be. Related Link: Love & Libations: Autumn + Red Wine = Love Ready to get it in? Here are some celebrity-inspired suggestions: Branson Cognac Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson is always up to something. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

June 26, 1995

Volume$3.00Mail Registration ($2.8061 No. plusNo. 1351 .20 GST)21-June 26, 1995 rn HO I. Y temptation Z2/Z4-8I026 BUM "temptation" IN ate, JUNE 27th FIRST SIN' "jersey girl" r"NAD1AN TOUR DATES June 24 (2 shows) - Discovery Theatre, Vancouver June 27 a 28 - St. Denis Theatre, Montreal June 30 - NAC Theatre, Ottawa July 4 - Massey Hall, Toronto PRODUCED BY CRAIG STREET RPM - Monday June 26, 1995 - 3 theUSArts ireartstrade of and andrepresentativean artsbroadcasting, andculture culture Mickey film, coalition coalition Kantorcable, representing magazine,has drawn getstobook listdander publishing companiesKantor up and hadthat soundindicated wouldover recording suffer thatKantor heunder wasindustries. USprepared trade spokespersonCanadiansanctions. KeithThe Conference for announcement theKelly, coalition, nationalof the was revealed Arts, expecteddirector actingthat ashortly. of recent as the a FrederickPublishersThe Society of Canadaof Composers, Harris (SOCAN) Authors and and The SOCANand Frederick Music project.the preview joint participation Canadian of SOCAN and works Harris in this contenthason"areGallup the theconcerned information Pollresponsibilityto choose indicated about from.highway preserving that to He ensure a and alsomajority that our pointedthere culturalthe of isgovernment Canadiansout Canadian identity that in MusiccompositionsofHarris three MusicConcert newCanadian Company at Hallcollections Toronto's on pianist presentedJune Royal 1.of Monica Canadian a Conservatory musical Gaylord preview piano of Chatman,introducedpresidentcomposers of StevenGuest by the and their SOCAN GellmanGaylord.speaker respective Foundation, and LouisThe composers,Alexina selections Applebaum, introduced Louie. Stephen were the originatethatisspite "an 64% of American the ofKelly abroad,cultural television alsodomination policies mostuncovered programs from in of place ourstatisticsscreened the media."in US; Canada indicatingin 93% Canada there of composersdesignedSeriesperformed (Explorations toThe the introduceinto previewpieces. -

Sylvester You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sylvester You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) Country: Netherlands Released: 1978 Style: Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1654 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1505 mb WMA version RAR size: 1941 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 755 Other Formats: VOC WMA VOX FLAC DMF MP3 DTS Tracklist A You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) 6:34 B Dance (Disco Heat) 5:47 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Fantasy Records Made By – Festival Records Pty. Ltd. Published By – Copyright Control Published By – Castle Credits Producer – Harvey Fuqua Notes Produced by Harvey Fuqua for Honey Records Productions. Made in Australia by Festival Records Pty. Ltd. ℗ Fantasy Records, U.S.A. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A runout): SMX53617 2A Matrix / Runout (Side B runout): SMX53618 2A Matrix / Runout (Side A label): MX53617 Matrix / Runout (Side B label): MX53618 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year You Make Me Feel BZC 4405, BZ Fantasy, BZC 4405, BZ Sylvester (Mighty Real) / Dance Germany 1978 4405 Fantasy 4405 (Disco Heat) (12") You Make Me Feel 9135 Sylvester Carrere 9135 France 1990 (Mighty Real) (12") You Make Me Feel FTC 160 Sylvester Mighty Real (7", Fantasy FTC 160 UK 1978 Single, Promo) You Make Me Feel K 7247 Sylvester Fantasy K 7247 New Zealand 1978 (Mighty Real) (7") You Make Me Feel K052Z-61678 Sylvester Fantasy K052Z-61678 Netherlands 1978 (Mighty Real) (12") Related Music albums to You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) by Sylvester Sylvester - Living Proof Sylvester - Step II Byron Stingily - You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) Part I Various - Disco Dancin' 78 Various - Disco Heat Various - Billboard Top Dance Hits 1978 Jimmy Somerville - Mighty Real Sylvester - Stars. -

PDF Download Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall Kindle

JUDY GARLANDS JUDY AT CARNEGIE HALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Manuel Betancourt | 144 pages | 14 May 2020 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781501355103 | English | New York, United States Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall PDF Book Two of her classmates in school were Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. In fact when you see there are tributes to a band that never existed The Rutles and The Muppet Show you could argue this one has run its course Her father was a butcher. Actor Psycho. Actor Alexis Zorbas. The following year, he played the lead character in the first Mickey McGuire short film. Minimal wear on the exterior of item. Self Great Performances. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab Any international shipping and import charges are paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. Actress The Shining. Carol Channing was born January 31, , at Seattle, Washington, the daughter of a prominent newspaper editor, who was very active in the Christian Science movement. He was married to Thomas Kirdahy. Marilyn Monroe was an American actress, comedienne, singer, and model. Actor Pillow Talk. Alone Together. Romantic Sad Sentimental. He first took the stage as a toddler in his parents vaudeville act at 17 months old. Moving to the center of the stage, she sings with emotion as her gloved hand paints the air above her head. He made his first film appearance in Tell Your Friends Share this list:. Kay Thompson Soundtrack Funny Face Sleek, effervescent, gregarious and indefatigable only begins to describe the indescribable Kay Thompson -- a one-of-a-kind author, pianist, actress, comedienne, singer, composer, coach, dancer, choreographer, clothing designer, and arguably one of entertainment's most unique and charismatic Dropped out of high school at the age of fifteen My Profile. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Handout 2 - Sylvester Biography Sylvester Was Born September 6, 1947, in the Watts Neighbor- Hood of Los Angeles, California

Handout 2 - Sylvester Biography Sylvester was born September 6, 1947, in the Watts neighbor- hood of Los Angeles, California. He spent most of his childhood in a church until his preteen years, when news of his sexuality spread throughout the community. Sylvester, whose childhood nickname was “Dooni,” was not completely accepted by his mother and eventually left home as a teenager, but returned home several times before leaving Watts by 1970. Sylvester found acceptance from his grandmother and as a member of the group the Disquotays, which featured black drag queens and trans women. In the late 1960s, Sylvester accompa- nied members of the Disquotays around Los Angeles. He began to dress in drag, even appearing in his graduation picture in a blue chiffon dress and beehive hairdo. His style was often described as androgynous, combining both feminine and masculine influences. After the Disquotays disbanded, Sylvester moved to San Francisco, and soon joined the drag troupe the Cockettes. After the Cockettes gained some popularity from San Francisco locals, celebrities, and publications like Rolling Stone, the show went on the road, travelling to cities with prominent drag and LGBTQ+ scenes. Sylvester’s performance during the Cockette’s shows often attracted the most attention. He claimed to have sought inspiration from black performers and singers Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday, and was offered his own recording contract after he left the Cockettes. Sylvester began recording and performing with a rock band known together as Sylvester and the Hot Band. And while they opened for famous musicians such as David Bowie, Sylvester and the Hot Band were commercially unsuccessful. -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Eyez on Me 2PAC – Changes 2PAC - Dear Mama 2PAC - I Ain't Mad at Cha 2PAC Feat

2 UNLIMITED- No Limit 2PAC - All Eyez On Me 2PAC – Changes 2PAC - Dear Mama 2PAC - I Ain't Mad At Cha 2PAC Feat. Dr DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN - California Love 311 - Amber 311 - Beautiful Disaster 311 - Down 3 DOORS DOWN - Away From The Sun 3 DOORS DOWN – Be Like That 3 DOORS DOWN - Behind Those Eyes 3 DOORS DOWN - Dangerous Game 3 DOORS DOWN – Duck An Run 3 DOORS DOWN – Here By Me 3 DOORS DOWN - Here Without You 3 DOORS DOWN - Kryptonite 3 DOORS DOWN - Landing In London 3 DOORS DOWN – Let Me Go 3 DOORS DOWN - Live For Today 3 DOORS DOWN – Loser 3 DOORS DOWN – So I Need You 3 DOORS DOWN – The Better Life 3 DOORS DOWN – The Road I'm On 3 DOORS DOWN - When I'm Gone 4 NON BLONDES - Spaceman 4 NON BLONDES - What's Up 4 NON BLONDES - What's Up ( Acoustative Version ) 4 THE CAUSE - Ain't No Sunshine 4 THE CAUSE - Stand By Me 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Amnesia 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Don't Stop 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER – Good Girls 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Jet Black Heart 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER – Lie To Me 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - She Looks So Perfect 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Teeth 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - What I Like About You 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER - Youngblood 10CC - Donna 10CC - Dreadlock Holiday 10CC - I'm Mandy ( Fly Me ) 10CC - I'm Mandy Fly Me 10CC - I'm Not In Love 10CC - Life Is A Minestrone 10CC - Rubber Bullets 10CC - The Things We Do For Love 10CC - The Wall Street Shuffle 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Closer To The Edge 30 SECONDS TO MARS - From Yesterday 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Kings and Queens 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Teeth 30 SECONDS TO MARS - The Kill (Bury Me) 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Up In The Air 30 SECONDS TO MARS - Walk On Water 50 CENT - Candy Shop 50 CENT - Disco Inferno 50 CENT - In Da Club 50 CENT - Just A Lil' Bit 50 CENT - Wanksta 50 CENT Feat. -

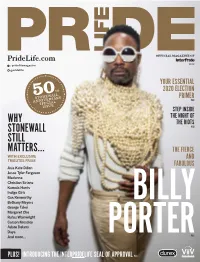

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

LGBTQ Role Models & Symbols

LGBTQ ROLE MODELS & SYMBOLS lgbtq Role Models Advocacy 4 Education 28 Stella Christie-Cooke Costa Kasimos Denise Cole Susan Rose Nancy Ruth Math & Science 31 Arts & Entertainment 9 Rachel Carson Trey Anthony Magnus Hirschfeld Jacinda Beals Alan Turing Georgina Beyer Leon Chisholm Religion 35 Portia DeGeneres Rev. Dr. Brent Hawkes, Christopher House C.M. Robert Joy Jane Lynch Sports 37 Greg Malone Rick Mercer John Amaechi Seamus O’Regan Martina Navratilova Gerry Rogers Mark Tewksbury Tommy Sexton Lucas Silveira Wanda Sykes This section includes profiles of a number of people who are active locally and nationally, or who have made contributions to history, or who are well-known personalities. Many have links to Newfoundland and Labrador. Public figures who are open about being members of the LGBTQ communities help to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues and foster acceptance in the general population. AdvocAcy Stella returned to Happy Valley-Goose Bay at the beginning of her career as a social worker in 2007. It soon became very clear to her that, despite Canada’s progress in legally recognizing the rights of queer individuals, there continued to be many gaps in the system and many individuals continued to struggle with a sense of isolation. Identifying as a queer person of Aboriginal ancestry, Stella continued to experience this first hand. Witnessing the impact this was having on her community, she became very motivated to bring others together to help address these gaps and create a sense of unity b. April 23, 1984 throughout Labrador. In 2009, Stella co-founded Labrador’s Safe Alliance, a group focused Stella Christie-Cooke was born in Winnipeg, on providing support and Manitoba. -

Sylvester Step II Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sylvester Step II mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul Album: Step II Country: US Released: 1978 Style: Soul, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1196 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1310 mb WMA version RAR size: 1615 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 522 Other Formats: MIDI AA AHX VOX ASF APE WAV Tracklist Hide Credits You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) A1 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Tip Wirrick*, SylvesterWritten-By – Wirrick*, Sylvester Dance (Disco Heat) (Cont.) A2 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Eric Robinson Written-By – Robinson*, Orsborn* B1 Dance (Disco Heat) (Concl.) I Took My Strength From You (Cont.) B2 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – SylvesterWritten-By – Bacharach - David* C1 I Took My Strength From You (Concl.) C2 You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) (Epilogue) Grateful C3 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Michael C. Finden*, SylvesterWritten-By – Finden*, Sylvester Was It Something That I Said D1 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – SylvesterWritten-By – Fuqua*, Sylvester Just You And Me Forever D2 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Eric Robinson Bass – James Jamerson Jr.Drums – James GadsonWritten-By – Robinson*, Orsborn* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Fantasy Records Copyright (c) – Fantasy Records Recorded At – Fantasy Studios Recorded At – Conway Studios Recorded At – Clark-Brown Audio Mixed At – Fantasy Studios Mastered At – Kendun Recorders Produced For – Honey Records Productions Credits Arranged By [Strings And Horns] – Leslie Drayton Art Direction – Phil Carroll Backing Vocals – Izora Rhodes*, Martha Wash Bass – Bob Kingson (tracks: A1 to B3) Concertmaster, Contractor [String Contractor] – Charles Veal* Contractor [Horn Contractor] – George Bohanon Design – Dennis Gassner Drums – Randy Merritt (tracks: A1 to B3) Engineer [Assistant] – Wally Buck Engineer [Recording] – Buddy Bruno, Eddie Bill Harris Guitar – Tip Wirrick* Lead Vocals, Piano [Acoustic] – Sylvester Mastered By [Mastering] – George Horn Organ, Electric Piano, Clavinet – Michael C.