Thesis, Books Are Created and Madee by People, and Not Just Those Involved in the Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P.C. Lauinger; Mary W

GEORGETOWN Newsletter 23 August 1988 621b;;;; AsSOcldtes GEORGETOWN UNIVERSI1Y LIBRARY 37TH & 0 STREETS, NW WASHINGTON , D. C. 20057 P. C. Lauinger - the Passing of a Friend The Artist HimlHer Self It is with genuine sadness that we report the The late James Elder, rare book librarian at the death on February 20, 1988 of Mr. P. C. Law Library of the Library of Congress, system Lauinger, one of the library's staunchest sup atically collected fine art, principally prints and porters and a true gentleman in the best sense of drawings, for more than thirty years. He left a that word. P.c., as he was universally known, collection of more than 1,000 pieces at his death graduated from the College in 1922, and in 1981. Towards the end of his collecting career throughout his lifetime maintained a special he began to specialize in artists' self-portraits. affection for and dedication to his alma mater. His limited means dictated further specialization He served on the Board of Regents, the Univer on the work of living artists and on 20th century sity President's Council under Father Edward American and British printmakers. The library Bunn, S.J., and was appointed in 1968 one of has recently acquired, along with 58 other the first laymen to serve on the University's works, the 392 self-portraits comprising virtually Board of Directors. the entirety of Elder's collection in this field. In 1956 Mr. Lauinger was awarded the John Carroll Award, which the Alumni Association confers annually upon a distinguished alumnus/a in recognition of lifetime achievement and out standing service to Georgetown Univeristy. -

Vertov: Between the Organism and the Machine

Vertov: Between the Organism and the Machine MALCOLM TURVEY In every living being, we find that those things which we call parts are inseparable from the Whole to such an extent, that they can only be conceived in and with the latter; and the parts can neither be the measure of the Whole, nor the Whole be the measure of the parts. — Goethe I The standard reading of the work of Dziga Vertov argues that, due to his affiliation with the Constructivist group of avant-garde artists that emerged in the Soviet Union after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Vertov employed the machine as the model for both his films and the new Soviet society depicted in them. In The Material Ghost, Gilberto Perez writes: [Vertov’s] Man with a Movie Camera [1929] pictures the city as a vast machine seen by the omnipresent seeing machine that is the camera. The structure of Vertov’s films, their aggregate space pieced together in the cutting room out of all the manifold things the mechanical eye can see, suggests the constructions of the engineer so prized in [the] new Soviet society.1 The centrality of the machine to Constructivist theory and practice, as well as to Vertov’s work, is beyond dispute. However, it has obscured the influence of other models on Vertov as he came to make Man with a Movie Camera in the late 1920s, including one that is often thought of as antithetical to the machine, namely, the organism. Most obviously, Man with a Movie Camera is structured according to the daily cycle of a complex living organism such as an animal or human being—sleep, 1. -

{Septcmber 1966} A. J. Davis

{septcmber 1966} SA TURN IB lliFLIGHT PHOTOGRAPHIC lNSTRUMENTATION SYSTEM by A. J. Davis t>,L. ttas&ler, Jr. MEASURING BRANCH ASTRIONICS LA.BORATORY GEORGE C. MARSHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER Huntsville, Alabama Fon INTERNA L USE ONLY MSFC • Form \094 (Mny 1961) GEORGE C. MARSHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER SATURN IB INFLIGHT PHOTOGRAPHIC INSTRUMENTATION SYSTEM By A. J. Davis P. L. Hassler, Jr. Measuring Branch Astrionics Laboratory George C. Marshall Space Flight Center H1mtsville, Alabama ABSTRACT This Internal Note presents the development of the Saturn inflight photo graphic instrumentation program from its original development req_uirement concept to the flight hardware application on Saturn vehicles. A comprehensive description of the inflight photographic instrumentation system is given along with data concerning testing, operation, application, and evaluation of the system after recovery. This Internal Note shows that the system has been successfully developed, that valuable information has been obtained from film retrieved from recovered capsules, and that the system can be used·with a high degree of reliability. NASA-GEORGE C. MARSHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER INTERNAL NOTE SATURN ID INFLIGHT PHOTOGRAPHIC WSTRUMENTATION SYSTEM by A. J. Davis P. L. Hassler, Jr. ASTRIONICS LABORATORY PROPULSION AND VEHICLE ENGINEERING LABORATORY TABLE Or CONTENTS Fage SECTION I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Project Hi.story 1 B. Inflight Photographic Instru�entation System 1 SECTION II. CAMERA AND OPTICAL AIDS 6 A. Camera . 6 B. Timer 7 c. Fiberoptic Bundle 9 D. Lenses . 10 E. Film . 11 F. Lighting . 13 G. Support Structure 21 H. Testing 28 SECTION III. CAPSULE EJECTION SYSTEM 36 A. Component Description 36 B. System Operation . 36 C. -

High Speed Imaging Pr Wilfried Uhring University of Strasbourg and CNRS Icube Laboratory, UMR 7357

NetWare 2015 Keynote : High Speed Imaging Pr Wilfried Uhring University of Strasbourg and CNRS Icube laboratory, UMR 7357 Wilfried Uhring ©ICube Icube, University of Strasbourg and CNRS Outline 2 • Just history and a state of the art … Wilfried Uhring 15:09 Icube, University of Strasbourg and CNRS 3 19th century - Fathers of Photography This image cannot currently be displayed. 1826 - Joseph Niépce – Plate coated with Judea bitumen – Mean exposure time 10 hours • 1838 - Louis Daguerre – Silver plate exposed to chemical vapor – latent image that has to be « fixed » – Daguerréotype – Mean exposure time 30 min – French government bought the invention and give it to the world Boulevard du temple - Paris Wilfried Uhring 15:09 Icube, University of Strasbourg and CNRS 4 19th – Birth of High speed photography • 1878 Eadweard Muybridge – Use of collodion allows short fast exposure time but have to be used before It get dry – Mean exposure time 500µs – Use 24 different cameras triggered by a string Only 24 frames Wilfried Uhring 15:09 Icube, University of Strasbourg and CNRS 19th – birth of cinematography 5 • Louis Le Prince – 1886: Use of multi lens device • Only 16 frames: a recurrent problem in high speed imaging …… – 1888: single lens with stripping film • 10 – 20 frames per second Roundhay Garden Scene Wilfried Uhring 15:09 Icube, University of Strasbourg and CNRS 6 20th century – first real high speed camera • 1926: two high speed camera systems British Heape-Gryll American Francis Jenkins • 4 tonnes, 8 horsepower • 5000 frames per second This image cannot• currently be displayed. Film drum This image cannot currently be displayed. -

Local Motion Picture Exhibition in Auburn, from 1894-1928: A

LOCAL MOTION PICTURE EXHIBITION IN AUBURN, FROM 1894-1928: A CULTURAL HISTORY FROM A COMMUNICATION PERSPECTIVE Danielle E. Williams Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this thesis is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. ______________________ Danielle E. Williams Certificate of Approval: _________________________ _________________________ Susan L. Brinson J. Emmett Winn, Chair Professor Associate Professor Communication and Journalism Communication and Journalism _________________________ _________________________ George Plasketes Stephen L. McFarland Professor Acting Dean Communication and Journalism Graduate School LOCAL MOTION PICTURE EXHIBITION IN AUBURN, FROM 1894-1928: A CULTURAL HISTORY FROM A COMMUNICATION PERSPECTIVE Danielle E. Williams A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Auburn, Alabama August 5, 2004 LOCAL MOTION PICTURE EXHIBITION IN AUBURN, FROM 1894-1928: A CULTURAL HISTORY FROM A COMMUNICATION PERSPECTIVE Danielle E. Williams Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this thesis at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. _______________________ Signature of Author _______________________ Date Copy sent to: Name Date iii VITA Danielle Elizabeth Williams was born September 11, 1980, in Springfield, Massachusetts, to Earle and Patricia Williams. After moving across the country and attending high school in Hendersonville, Tennessee, and Lead, South Dakota, she graduated from Olive Branch High School in Olive Branch, Mississippi, in 1998. In September 1998, Danielle started Auburn University, where she majored in Mass Communication. In addition to her academic studies, she was involved with Eagle Eye News, where she served as an Assistant Director from 2000-2001, and the Auburn Film Society, where she served as President from 2000-2004. -

Louis Le Prince Came Close to Achieving a Successful Process of Cinematography

CINEMATOGRAPHY Pioneers of Early Cinema: Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince (1841-1890?) Though he lacked the financial backing and research facilities of Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers, the acknowledged pioneers of motion pictures and the cinema, and did not live to exploit his invention commercially, Louis Le Prince came close to achieving a successful process of cinematography. Le Prince was born in Metz on 28 August 1841. His father, a French Army officer, was a friend of the photographic inventor, Jacques Louis Mandé Daguerre, and the young Louis often visited his studio. Le Prince studied chemistry and physics at the University of Leipzig then worked as a photographer and painter. In 1866 he met and became friends with John Whitley, a young British engineer. At his invitation, Le Prince came to Britain, to the Yorkshire city of Leeds, where he joined the family engineering firm, Whitley Partners, first as a designer and then as the manager of the valve department. In 1869, Le Prince married Elizabeth Whitley. During the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) Le Prince went to France to enlist in the French Army. In the siege of Paris, he was an officer of Volunteers. On his return to Britain, he and his wife established the Leeds Technical School of Art in Park Square, Leeds. He specialised in the tinting and firing of photographic images on enamel, ceramic and glass. Le Prince moved to New York in 1882 with his family to work on the development and promotion of the Lincrusta wallpaper process, in which John Whitley had an interest. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Newsletter Volume 19 / No

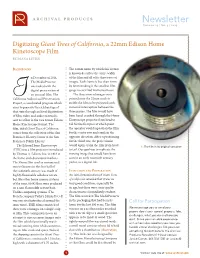

Newsletter Volume 19 / No. 3 / 2015 Digitizing Giant Trees of California, a 22mm Edison Home Kinetoscope Film BY DIANA LITTLE BACKGROUND The 22mm name by which this format is known describes the entire width n December of 2014, of the film and all of its three rows of The MediaPreserve images. Each frame is less than 4mm was tasked with the by 6mm making it the smallest film digital preservation of gauge to ever find mainstream use. an unusual film. The The three rows of images were ICalifornia Audiovisual Preservation printed onto the 22mm stock to Project, a coordinated program which enable the film to be projected with aims to preserve the rich heritage of minimal interruption between the that state through archival digitization three passes. The film would have of film, video and audio materials, been hand-cranked through the Home sent us a film in the rare 22mm Edison Kinetoscope projector from head to Home Kinetoscope format. The tail for the first pass at which point film, titled Giant Trees of California, the operator would reposition the film comes from the collection of the San for the center row and crank in the Francisco History Center at the San opposite direction. After repositioning Francisco Public Library. for the third row, the projectionist The Edison Home Kinetoscope would again crank the film from head 1: The film in its original container (EHK) was a film projector introduced to tail. Our goal was to replicate the by Thomas A. Edison, Inc. in 1912 to moving image that would have been the home and educational markets. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

Visions of Electric Media Electric of Visions

TELEVISUAL CULTURE Roberts Visions of Electric Media Ivy Roberts Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Visions of Electric Media Televisual Culture Televisual culture encompasses and crosses all aspects of television – past, current and future – from its experiential dimensions to its aesthetic strategies, from its technological developments to its crossmedial extensions. The ‘televisual’ names a condition of transformation that is altering the coordinates through which we understand, theorize, intervene, and challenge contemporary media culture. Shifts in production practices, consumption circuits, technologies of distribution and access, and the aesthetic qualities of televisual texts foreground the dynamic place of television in the contemporary media landscape. They demand that we revisit concepts such as liveness, media event, audiences and broadcasting, but also that we theorize new concepts to meet the rapidly changing conditions of the televisual. The series aims at seriously analyzing both the contemporary specificity of the televisual and the challenges uncovered by new developments in technology and theory in an age in which digitization and convergence are redrawing the boundaries of media. Series editors Sudeep Dasgupta, Joke Hermes, Misha Kavka, Jaap Kooijman, Markus Stauff Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Ivy Roberts Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: ‘Professor Goaheadison’s Latest,’ Fun, 3 July 1889, 6. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden -

Creativity at the Workplace

The Law and Economics of Creativity at the Workplace ISSN 1045-6333 THE LAW AND ECONOMICS OF CREATIVITY IN THE WORKPLACE Barak Y. Orbach Discussion Paper No. 356 03/2002 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 The Center for Law, Economics, and Business is supported by a grant from the John M. Olin Foundation. This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ The Law and Economics of Creativity at the Workplace JEL Classes K11, K19, P1 THE LAW AND ECONOMICS OF CREATIVITY AT THE WORKPLACE Barak Y. Orbach* (February, 2002) Abstract Technological and legal developments led to the rise of employed creativity in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The new class of employers claimed the rights in the creative products produced by artists and inventors employed by it and after a short struggle its demands were satisfied: by and large the law acknowledges the rights of employers in creative products produced by workers (employees and contractors), just as it acknowledges the rights of employers in any other products. This legal victory, although took place almost a century ago, is still fiercely debated among scholars and participants in creative industries. In the past century, thousands of disputes between employers and workers over rights in creative products were brought before the courts and inspired voluminous commentary on the topic. Nonetheless, the study of the nature and structure of the law that allocates the rights between employers and workers has generally been neglected. This paper studies the organization of creativity at the workplace, presents a general framework for understanding the present allocation rules, evaluates these rules, and offers simple guidelines for designing better rules, when needed. -

Moving Pictures: the History of Early Cinema by Brian Manley

Discovery Guides Moving Pictures: The History of Early Cinema By Brian Manley Introduction The history of film cannot be credited to one individual as an oversimplification of any his- tory often tries to do. Each inventor added to the progress of other inventors, culminating in progress for the entire art and industry. Often masked in mystery and fable, the beginnings of film and the silent era of motion pictures are usually marked by a stigma of crudeness and naiveté, both on the audience's and filmmakers' parts. However, with the landmark depiction of a train hurtling toward and past the camera, the Lumière Brothers’ 1895 picture “La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon” (“Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory”), was only one of a series of simultaneous artistic and technological breakthroughs that began to culminate at the end of the nineteenth century. These triumphs that began with the creation of a machine that captured moving images led to one of the most celebrated and distinctive art forms at the start of the 20th century. Audiences had already reveled in Magic Lantern, 1818, Musée des Arts et Métiers motion pictures through clever uses of slides http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Magic-lantern.jpg and mechanisms creating "moving photographs" with such 16th-century inventions as magic lanterns. These basic concepts, combined with trial and error and the desire of audiences across the world to see entertainment projected onto a large screen in front of them, birthed the movies. From the “actualities” of penny arcades, the idea of telling a story in order to draw larger crowds through the use of differing scenes began to formulate in the minds of early pioneers such as Georges Melies and Edwin S.