Topography and Hydrography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Field Development-A3-EN-02112020 Copy

FIELD DEVELOPMENTS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC NORTH EAST AND NORTH WEST SYRIA ٢٠٢٠ November ٢ - October ٢٧ Violations committed by ١,٠٩١ the Regime and its Russian ally of the ceasefire truce ٢٠٢٠ November ٢ Control Parties ;٢٠٢٠ March ٥ After the Turkish and Russian Presidents reached the ceasefire truce agreement in Idleb Governorate on the warplanes of the regime and its Russian ally didn’t bomb North Western Syria ever since; yet the regime continued Russian warplanes have ;٢٠٢٠ June ٢ targeting the cities and towns there with heavy artillery and rocket launchers; on again bombed northwestern Syria, along with the regime which continued targeting NW Syria with heavy artillery and ١,٠٩١ rocket launchers. Through its network of enumerators, the Assistance Coordination Unit ACU documented violations of the truce committed by the regime and its Russian ally as of the date of this report. There has been no change in the control map over the past week; No joint Turkish-Russian military patrols were carried the regime bombed with heavy ,٢٠٢٠ October ٢٧ on ;٢٠٢٠ November ٢ - October ٢٧ out during the period between artillery the area surrounding the Turkish observation post in the town of Marj Elzohur. The military actions carried out ٣ civilians, including ٢٣ civilians, including a child and a woman, and wounded ٨ by the Syrian regime and its allies killed Regime .women ٣ children and Opposition group The enumerators of the Information Management Unit (IMU) of the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) documented in Opposition group affiliated by Turkey (violations of the truce in Idleb governorate and adjacent Syrian democratic forces (SDF ٦٨ m; ٢٠٢٠ November ٢ - October ٢٧ the period between countrysides of Aleppo; Lattakia and Hama governorates. -

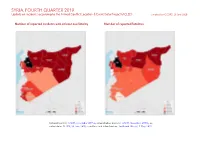

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Civilians in Hama

Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama www.stj-sy.org Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama Two young men were kidnapped by the National Defense Militia; the other 11, belonging to the same family, were abducted by a security service in Hama city. The abductees were all released in return for a ransom Page | 2 Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama www.stj-sy.org In November 2018 and February 2019, 13 civilians belonging to two different families were kidnapped by security services and the militias backing them in Hama province. The kidnapped persons were all released after a separate ransom was paid by each of the families. Following their release, a number of the survivors, 11 to be exact, chose to leave Hama to settle in Idlib province. The field researchers of Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ contacted several of the abduction survivors’ relatives, who reported that some of the abductees were subjected to severe torture and deprived of medications, which caused one of them an acute health deterioration. 1. The Kidnapping of Brothers Jihad and Abduljabar al- Saleh: The two young men, Jihad, 28-year-old, and Abduljabar, 25-year-old, are from the village of al-Tharwat, eastern rural Hama, from which they were displaced after the Syrian regular forces took over the area late in 2017, to settle in an IDP camp in Sarmada city. The brothers, then, decided to undergo legalization of status/sign a reconciliation agreement with the Syrian government to obtain passports and move in Saudi Arabia, where their family is based. -

Syria, a Country Study

Syria, a country study Federal Research Division Syria, a country study Table of Contents Syria, a country study...............................................................................................................................................1 Federal Research Division.............................................................................................................................2 Foreword........................................................................................................................................................5 Preface............................................................................................................................................................6 GEOGRAPHY...............................................................................................................................................7 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS....................................................................................8 NATIONAL SECURITY..............................................................................................................................9 MUSLIM EMPIRES....................................................................................................................................10 Succeeding Caliphates and Kingdoms.........................................................................................................11 Syria.............................................................................................................................................................12 -

To Read the Full Report As a PDF, Follow This Link

Arbitrary Deprivation of Truth and Life An accurate, transparent, and non-discriminatory approach must be adopted by the Syrian State when issuing “death statements” 1 2 Executive Summary Hostilities forced Samar al-Hasan, 40, and her family to flee their home in Ma'arrat al-Nu'man city and settle in a makeshift camp in Harem city, within rural Idlib province. Before the family fled, Samar’s husband was killed in a regime rocket attack on their neighborhood. Now, Samar lives with her children in her family’s tent, unable to afford taking care of her children or herself without help. One source of her financial troubles is the Syrian government’s refusal to give Samar her husband’s death statement, a document which would allow her and her children to access her husband’s will. The wrinkles on Samar’s forehead speak of her suffering since her husband’s death in 2018. Even as she wistfully recalls for Syrians for Truth and Justice the comfortable years she spent in Ma'arrat al-Nu'man with her husband, she knows they will never return. A “death statement” formally documents the death of a person. Obtaining a death statement allows a widow to remarry – if she wishes – after the passage of her “Iddah”.1 A death statement is also required to initiate a ‘determination of heirship’ procedure by the deceased's heirs (incl. the wife, children, parents, and siblings). In Syria, “death statements” are distinct from “death certificates”. A death certificate is the document that confirms the occurrence of death, issued by the responsible local authorities or the institution in which the death took place, such as hospitals and prisons, or by the “Mukhtar” – the village or district chief, who keeps a local civil registry. -

Proactive Ismaili Imam: His Highness the Aga Khan Part - 2

Aga Khan IV Photo Credit: AKDN.org Proactive Ismaili Imam: His Highness the Aga Khan Part - 2 History: a live broadcast of the past, a joy of the present, and a treasure for the future. History has significant past knowledge, culture, and memories of ancestors wrapped in its womb. The historical monuments, art, music, culture, language, food, and traditional clothes educate people about who they are, where they are, and where they belong in the particular era. Furthermore, the deep roots of history help individuals to see the fruitful stems of growth. The growth in the field of economics, science, architecture, education, and the quality of life of people in this period of modernization. Therefore, destroying history from the lives of the people would be the same as cutting the roots of a tree. No matter how healthy species a tree may be from, it won’t be able to survive without its roots. Thus, history builds a path that leads toward the future. Therefore, without the presence of history, the growth of the future would be unknown. Hence, the proactive Ismaili Imam, the Aga Khan, is actively taking every possible step to preserve history by preserving the historical monuments and improving the quality of life of people within the ambit. One of the best examples of the Aga Khan’s work is in Syria, a country known for its Islamic history. Syria and Islamic civilization go a long way back in history. As His Highness the Aga Khan said, “Those of you who know the history of Syria, the history of cities such as Aleppo, you will know how much they have contributed to the civilisations of Islam, to the practices of Islam, to the search for truth not only within Muslim communities, but with Jewish communities, Christian communities. -

Flash Update | Monitoring Violence Against Healthcare Health Sector

Flash Update | Monitoring violence against healthcare Health Sector | Syria Hub Flash Update # 36 Date: 06/06/2019 Time of the incident: between 6.15 to 7.30 p.m. Location North-West Hama, Mahardah City HF Name & Type Al-Mahabah private hospital Attack type Violence with heavy weapons Incident On Thursday 6 June between 6.15 to 7.30 p.m., Al-Mahabah private hospital in North West Hama was reportedly targeted by Indirect rockets three times. Prior Health Facility The hospital was fully functioning, partially damaged, provided: 120 condition out-consultations (x-ray), 350-400 surgical operations (including CSs), 75-80 normal deliveries, 30 babies in incubator, 50 hospitalized patients during May 2019 Impact . The hospital was reportedly partially damaged, as follow: - Main façade, most glasses of the hospital were destroyed. - Some rooms (emergency room, general surgery, one patient room) have become out of service. - 10 air conditioners were destroyed. Victims of the Attack Total Deaths: (0) Health Care Providers: 0 Auxiliary Health Staff: 0 Patients: 0 Others: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Males: 0 Females: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Age < 15 years: 0 Age ≥ 15 years: 0 Total Injuries: (0) Health Care Providers: 0 Auxiliary Health Staff: 0 Patients: 0 Others: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Males: 0 Females: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Age < 15 years: 0 Age ≥ 15 years: 0 Disclaimer: The information presented in this document do not imply the opinion of the World Health Organization. Information were gathered through adopted tools (i.e., HeRAMS) & other sources of information, and all possible means have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this document. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. -

URGENT ACTION SYRIAN FATHER of THREE MISSING for 1403 DAYS Today Is Ali Mohammed Mostafa’S 55Th Birthday

UA: 101/17 Index: MDE 24/6176/2017 Syria 5 May 2017 URGENT ACTION SYRIAN FATHER OF THREE MISSING FOR 1403 DAYS Today is Ali Mohammed Mostafa’s 55th birthday. He is a father of three who has been forcibly disappeared for nearly four years, and his family still has no information about his fate or whereabouts. On 2 July 2013, Ali went missing after being taken from his family home in Damascus. On 2 July 2013, Ali Mohammed Mostafa, a businessman originally from Masyaf in Hama countryside, was at his family home in Damascus when he was arrested by Syrian government forces. On that morning, the neighbors informed his wife upon her arrival home that Syrian government forces raided the house, wrecked the furniture, tore clothes and papers, and arrested Ali at around 10:00 am. Since then, and despite various and continuous requests, Ali’s family has not received any confirmed information about his fate or whereabouts, which remain unknown. Ali Mohammed Mostafa was detained twice before. In 2006, he was arrested by Syrian government forces after attempting to resolve a local dispute in his town. Then, when the protests started in Syria in 2011, Ali participated in peaceful demonstrations and in a local committee created to provide aid to internally displaced people who had fled the violence in Hama. For this, he was detained in August 2011 for a month and a half. A close family member told Amnesty: “We do not know whether he is dead or alive. It torments us every day. Our only wish is that Ali celebrates his 56th birthday among us”. -

From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East

REVOLUTIONIZING REVOLUTIONIZING Mark Altaweel and Andrea Squitieri and Andrea Mark Altaweel From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East This book investigates the long-term continuity of large-scale states and empires, and its effect on the Near East’s social fabric, including the fundamental changes that occurred to major social institutions. Its geographical coverage spans, from east to west, modern- day Libya and Egypt to Central Asia, and from north to south, Anatolia to southern Arabia, incorporating modern-day Oman and Yemen. Its temporal coverage spans from the late eighth century BCE to the seventh century CE during the rise of Islam and collapse of the Sasanian Empire. The authors argue that the persistence of large states and empires starting in the eighth/ seventh centuries BCE, which continued for many centuries, led to new socio-political structures and institutions emerging in the Near East. The primary processes that enabled this emergence were large-scale and long-distance movements, or population migrations. These patterns of social developments are analysed under different aspects: settlement patterns, urban structure, material culture, trade, governance, language spread and religion, all pointing at population movement as the main catalyst for social change. This book’s argument Mark Altaweel is framed within a larger theoretical framework termed as ‘universalism’, a theory that explains WORLD A many of the social transformations that happened to societies in the Near East, starting from Andrea Squitieri the Neo-Assyrian period and continuing for centuries. Among other infl uences, the effects of these transformations are today manifested in modern languages, concepts of government, universal religions and monetized and globalized economies. -

DEATH by CHEMICALS RIGHTS the Syrian Government’S Widespread and Systematic Use WATCH of Chemical Weapons

HUMAN DEATH BY CHEMICALS RIGHTS The Syrian Government’s Widespread and Systematic Use WATCH of Chemical Weapons Death by Chemicals The Syrian Government’s Widespread and Systematic Use of Chemical Weapons Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34693 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34693 Death by Chemicals The Syrian Government’s Widespread and Systematic Use of Chemical Weapons Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 6 To the UN Security Council ...................................................................................................... -

ANCIENT NECROPOLIS UNEARTHED Italian Archaeologists Lead Dig Near Palmyra

Home > News in English > News » le news di oggi » le news di ieri » 2008-12-17 12:11 ANCIENT NECROPOLIS UNEARTHED Italian archaeologists lead dig near Palmyra (ANSA) - Udine, December 17 - An Italian-led team of experts has uncovered a vast, ancient necropolis near the Syrian oasis of Palmyra. The team, headed by Daniele Morandi Bonacossi of Udine University, believes the burial site dates from the second half of the third millennium BC. The necropolis comprises around least 30 large burial mounds near Palmyra, some 200km northeast of Damascus. ''This is the first evidence that an area of semi-desert outside the oasis was occupied during the early Bronze Age,'' said Morandi Bonacossi. ''Future excavations of the burial mounds will undoubtedly reveal information of crucial importance''. The team of archaeologists, topographers, physical anthropologists and geophysicists also discovered a stretch of an old Roman road. This once linked Palmyra with western Syria and was marked with at least 11 milestones along the way. The stones all bear Latin inscriptions with the name of the Emperor Aurelius, who quashed a rebellion led by the Palmyran queen Zenobia in AD 272. The archaeologists also unearthed a Roman staging post, or ''mansio''. The ancient building had been perfectly preserved over the course of the centuries by a heavy layer of desert sand. The team from Udine University made their discoveries during their tenth annual excavation in central Syria, which wrapped up at the end of November. The necropolis is the latest in a string of dazzling finds by the team. Efforts have chiefly focused on the ancient Syrian capital of Qatna, northeast of modern-day Homs.