Syrian Qanat Romani: History, Ecology, Abandonment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Out of Water Civilizations Emerge Focus on Pre-Islamic Persian Empires

INFLUENCE OF WATER MANAGEMENT ON EMPIRES 1 Out of Water Civilizations Emerge Focus on Pre-Islamic Persian Empires Festival of the Passing of the Ice Dragon 8 April 2017 Pentathlon Entry - Literary Arts Research Paper INFLUENCE OF WATER MANAGEMENT ON EMPIRES 2 Abstract Water or the lack of it has the power to create or destroy empires. From prehistory to the current time period this has been shown to be true. The civilizations who have been able to harness water, transport it and conserve it are the societies that have risen to power. The Persian Empires, from the earliest to the last, were masters of water husbandry. They developed an underground transport system called qanats that enabled them to become one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen. Not only has their knowledge of water transport enabled the irrigation of fields, it provided water for domestic purposes in their homes, to air- condition their homes and allowed the use of sewage systems which helped to keep disease at bay. INFLUENCE OF WATER MANAGEMENT ON EMPIRES 3 Out of Water Civilizations Emerge – Focus on Pre-Islamic Persian Empires Water has controlled the rise and fall of great empires. Rome became a great power when it was able to harvest the water from the Mediterranean Sea, China’s Golden Age developed after the completion of the 1100 mile long Grand Canal for transport of goods and irrigation. Domination of the oceans by the Vikings gave rise to their success. Civilizations are driving by the way in which they respond to the challenges of their environment. -

The Clarion of Syria

AL-BUSTANI, HANSSEN,AL-BUSTANI, SAFIEDDINE | THE CLARION OF SYRIA The Clarion of Syria A PATRIOT’S CALL AGAINST THE CIVIL WAR OF 1860 BUTRUS AL-BUSTANI INTRODUCED AND TRANSLATED BY JENS HANSSEN AND HICHAM SAFIEDDINE FOREWORD BY USSAMA MAKDISI The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Simpson Imprint in Humanities. The Clarion of Syria Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The Clarion of Syria A Patriot’s Call against the Civil War of 1860 Butrus al-Bustani Introduced and Translated by Jens Hanssen and Hicham Safieddine Foreword by Ussama Makdisi university of california press University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2019 by Jens Hanssen and Hicham Safieddine This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hanssen, Jens, author & translator. -

The Origin of the Terms 'Syria(N)'

Parole de l’Orient 36 (2011) 111-125 THE ORIGIN OF THE TERMS ‘SYRIA(N)’ & SŪRYOYO ONCE AGAIN BY Johny MESSO Since the nineteenth century, a number of scholars have put forward various theories about the etymology of the basically Greek term ‘Syrian’ and its Aramaic counterpart Sūryoyo1. For a proper understanding of the his- tory of these illustrious names in the two different languages, it will prove useful to analyze their backgrounds separately from one another. First, I will discuss the most persuasive theory as regards the origin of the word ‘Syria(n)’. Secondly, two hypotheses on the Aramaic term Sūryoyo will be examined. In the final part of this paper, a new contextual backdrop and sharply demarcated period will be proposed that helps us to understand the introduction of this name into the Aramaic language. 1. THE ETYMOLOGY OF THE GREEK TERM FOR ‘SYRIA(N)’ Due to their resemblance, the ancient Greeks had always felt that ‘Syr- ia(n)’ and ‘Assyria(n)’ were somehow onomastically related to each other2. Nöldeke was the first modern scholar who, in 1871, seriously formulated the theory that in Greek ‘Syria(n)’ is a truncated form of ‘Assyria(n)’3. Even if his view has a few minor difficulties4, most writers still adhere to it. 1) Cf., e.g., the review (albeit brief and inexhaustive) by A. SAUMA, “The origin of the Word Suryoyo-Syrian”, in The Harp 6:3 (1993), pp. 171-197; R.P. HELM, ‘Greeks’ in the Neo-Assyrian Levant and ‘Assyria’ in Early Greek Writers (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation; University of Pennsylvania, 1980), especially chapters 1-2. -

Proactive Ismaili Imam: His Highness the Aga Khan Part - 2

Aga Khan IV Photo Credit: AKDN.org Proactive Ismaili Imam: His Highness the Aga Khan Part - 2 History: a live broadcast of the past, a joy of the present, and a treasure for the future. History has significant past knowledge, culture, and memories of ancestors wrapped in its womb. The historical monuments, art, music, culture, language, food, and traditional clothes educate people about who they are, where they are, and where they belong in the particular era. Furthermore, the deep roots of history help individuals to see the fruitful stems of growth. The growth in the field of economics, science, architecture, education, and the quality of life of people in this period of modernization. Therefore, destroying history from the lives of the people would be the same as cutting the roots of a tree. No matter how healthy species a tree may be from, it won’t be able to survive without its roots. Thus, history builds a path that leads toward the future. Therefore, without the presence of history, the growth of the future would be unknown. Hence, the proactive Ismaili Imam, the Aga Khan, is actively taking every possible step to preserve history by preserving the historical monuments and improving the quality of life of people within the ambit. One of the best examples of the Aga Khan’s work is in Syria, a country known for its Islamic history. Syria and Islamic civilization go a long way back in history. As His Highness the Aga Khan said, “Those of you who know the history of Syria, the history of cities such as Aleppo, you will know how much they have contributed to the civilisations of Islam, to the practices of Islam, to the search for truth not only within Muslim communities, but with Jewish communities, Christian communities. -

From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East

REVOLUTIONIZING REVOLUTIONIZING Mark Altaweel and Andrea Squitieri and Andrea Mark Altaweel From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East This book investigates the long-term continuity of large-scale states and empires, and its effect on the Near East’s social fabric, including the fundamental changes that occurred to major social institutions. Its geographical coverage spans, from east to west, modern- day Libya and Egypt to Central Asia, and from north to south, Anatolia to southern Arabia, incorporating modern-day Oman and Yemen. Its temporal coverage spans from the late eighth century BCE to the seventh century CE during the rise of Islam and collapse of the Sasanian Empire. The authors argue that the persistence of large states and empires starting in the eighth/ seventh centuries BCE, which continued for many centuries, led to new socio-political structures and institutions emerging in the Near East. The primary processes that enabled this emergence were large-scale and long-distance movements, or population migrations. These patterns of social developments are analysed under different aspects: settlement patterns, urban structure, material culture, trade, governance, language spread and religion, all pointing at population movement as the main catalyst for social change. This book’s argument Mark Altaweel is framed within a larger theoretical framework termed as ‘universalism’, a theory that explains WORLD A many of the social transformations that happened to societies in the Near East, starting from Andrea Squitieri the Neo-Assyrian period and continuing for centuries. Among other infl uences, the effects of these transformations are today manifested in modern languages, concepts of government, universal religions and monetized and globalized economies. -

Distribution List in ENG 22 6.Xlsx

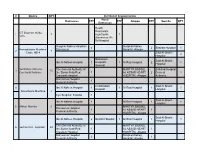

# Device QTY Distribution by governorates Rural Damascus QTY QTY Aleppo QTY Sweida QTY Damascus Health Directorate CT Scanner 16/32- 1 1 countryside 1 slice Damascus /Al- Tal Hospital Surgical Kidney Hospital - Surgical Kidney 2 2 Shahba Hospital 1 Hemodialysis Machine Damascus Hospital -Aleppo 2 7 Code: HE-4 Zaid Al-Shariti 2 Hospital Qalamoun Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 Hospitals 1 Al-Razi Hospital 2 1 Hospital General Ventilators Intensive Authority 3 10 The General Authority of MARTYR BASSEL Salkhad Hospital Care Adult Pediatric the Syrian Arab Red 1 AL ASSAD HEART 2 General 1 Crescent Hospital HOSPITAL -Aleppo Authority Damascus Hospital 1 General Authority Al-Zabadani Zaid Al-Shariti 4 Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital Hospital Anesthesia Machine 5 Eye Surgical hospital 1 Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital 5 Mobail Monitor 5 MARTYR BASSEL Damascus Hospital 1 AL ASSAD HEART 1 General Authority HOSPITAL -Aleppo Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 2 Qutaifa Hospital 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital The General Authority of MARTYR BASSEL 6 Suction Unit , Aspirator 10 the Syrian Arab Red 1 AL ASSAD HEART 1 Crescent Hospital HOSPITAL -Aleppo Damascus Hospital Surgical Kidney 2 1 General Authority Hospital -Aleppo Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 Qatana Hospital 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital The General Authority of MARTYR BASSEL the Syrian Arab Red 1 AL ASSAD HEART 1 Shahba Hospital 1 Crescent Hospital HOSPITAL -Aleppo 7 Ultrasonic Nebulizer 10 General -

Innovating Irrigation Technologies –

Innovating irrigation technologies – Four communities in the Southeastern Arabian Iron Age II 1 Sources of pictures (clockwise): Picture 1: Al-Tikriti 2010, 231 Picture 2: Cordoba and Del Cerro 2018, 95 Picture 3 : Charbonnier et al. 2017, 18 Picture 4: Map created by Anna Lipp, © WAJAP (www.wajap.nl) Contact details: Anna Lipp Hoge Rijndijk 94L 2313 KL Leiden [email protected] 0049 172 762 9184 2 Innovating irrigation technologies - Four communities in the Southeastern Arabian Iron Age II Innovating irrigation technologies. Four communities in the Southeastern Arabian Iron Age II. Anna Lipp MA Thesis Course and course code: MA thesis Archaeology, 4ARX-0910ARCH Supervisor: Dr. Bleda S. Düring Archaeology of the Near East University of Leiden, Faculty of Archaeology Leiden, 12.6.2019 final version 3 Table of contents Acknowlegdements p.4 Glossary p.5 I. Introduction and research questions p.6 II. Region and cultural history p.9 II.1 Geology p.9 II.2 Paleoclimate on the Arabian Peninsula p.11 II.3 Early Arabian Archaeology p.12 II.4 Iron Age Chronologies p.12 II.5 Settlement boom p.15 II.6 Settlement outlines p.18 II.7 Houses p.19 II.8 Columned rooms p.20 II.9 Subsistence activities and trade p.22 II.10 Pottery p.24 III. Theory and examples of irrigation systems, debates in Arabian Archaeology and methodology p.28 III.1 Theoretical approaches to irrigation p.28 III.2 Groundwater irrigation: wells for irrigation purposes p.30 III.3 Qanat-type falaj systems p.34 III.4 Gharrag falaj p.35 III.5 Ground- or surface water irrigation: Runoff irrigation p.36 III.6 Transporting water: mills p.37 III.7 Collecting water: cisterns p.39 III.8 Debates in Arabian Archaeology p.40 III.9 Methodology p.44 IV. -

Security Council Distr.: General 22 December 2016 English Original: Russian

United Nations S/2016/1081 Security Council Distr.: General 22 December 2016 English Original: Russian Letter dated 20 December 2016 from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General I have the honour to transmit herewith information bulletins from the Russian Centre for Reconciliation of Opposing Sides in the Syrian Arab Republic for the period 16-19 December 2016 (see annex). I should be grateful if the text of this letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) V. Churkin 16-22832 (E) 301216 030117 *1622832* S/2016/1081 Annex to the letter dated 20 December 2016 from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General Information bulletin of the Russian Centre for Reconciliation of Opposing Sides in the Syrian Arab Republic (16 December 2016) Reconciliation of opposing sides Over the past 24 hours, four ceasefire regime agreements have been signed with populated areas in Ladhiqiyah governorate (3) and Homs governorate (1). The number of populated areas that have joined the reconciliation process has increased to 1,061. Negotiations on joining the ceasefire regime continued with field commanders of armed groups in Damascus governorate and armed opposition units in Homs, Hama, Aleppo and Qunaytirah governorates. The number of armed groups that have announced their commitment to accepting and fulfilling the terms of the ceasefire is unchanged — it is still 94. Observance of the ceasefire regime Over the past 24 hours, there were 29 reports of shelling by armed group s in Damascus governorate (13), Aleppo governorate (12), Hama governorate (2) and Dar‘a governorate (2). -

Peter Magee Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Bryn Mawr College 101 North Merion Avenue Bryn Mawr PA 19010 USA

1 November 2016 Professor Peter Magee Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Bryn Mawr College 101 North Merion Avenue Bryn Mawr PA 19010 USA EDUCATION 1992-1996: PhD., Cultural Variability, Change and Settlement in Southeastern Arabia, 1300-300 B.C. University of Sydney. 1987-1990: B.A. (Honours Class 1). University of Sydney. APPOINTMENTS Current: Chair and Professor, Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology, Bryn Mawr College Current: Director, Middle Eastern Studies Program, Bryn Mawr College. 2010-2012: Special Assistant to the President of Bryn Mawr College on International Education Initiatives 2006–2013: Associate Professor, Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology, Bryn Mawr College. 2002-2006: Assistant Professor, Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology, Bryn Mawr College. 1998-2001:U2000 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Archaeology, University of Sydney. 1997: Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Research Fellow, Department of Near Eastern Archaeology and Languages, University of Gent, Belgium. 1996: Visiting Lecturer, Department of Archaeology, University of New England, Australia. 1992-1995: Associate Lecturer, Department of Archaeology, University of Sydney. 1995: Museum Assistant, Nicholson Museum, University of Sydney. FIELD EXPERIENCE 1994-Current: Director, Excavations at Muweilah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2007-Current: Director, Excavations at Tell Abraq and Hamriyah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 1997-2001: co-Director with the British Museum, Excavations at Akra, Pakistan. 1994: Survey Director, Russian Excavations at Qana, Yemen. 1989-1993: Student participation in excavations in Australia, Greece, Jordan, Syria and the UAE. RESEARCH AWARDS AND GRANTS 2014: Research Funding Agreement with the Government of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates for excavations at Muweilah and Tell Abraq: Contribution to cover costs of excavation etc. -

ANCIENT NECROPOLIS UNEARTHED Italian Archaeologists Lead Dig Near Palmyra

Home > News in English > News » le news di oggi » le news di ieri » 2008-12-17 12:11 ANCIENT NECROPOLIS UNEARTHED Italian archaeologists lead dig near Palmyra (ANSA) - Udine, December 17 - An Italian-led team of experts has uncovered a vast, ancient necropolis near the Syrian oasis of Palmyra. The team, headed by Daniele Morandi Bonacossi of Udine University, believes the burial site dates from the second half of the third millennium BC. The necropolis comprises around least 30 large burial mounds near Palmyra, some 200km northeast of Damascus. ''This is the first evidence that an area of semi-desert outside the oasis was occupied during the early Bronze Age,'' said Morandi Bonacossi. ''Future excavations of the burial mounds will undoubtedly reveal information of crucial importance''. The team of archaeologists, topographers, physical anthropologists and geophysicists also discovered a stretch of an old Roman road. This once linked Palmyra with western Syria and was marked with at least 11 milestones along the way. The stones all bear Latin inscriptions with the name of the Emperor Aurelius, who quashed a rebellion led by the Palmyran queen Zenobia in AD 272. The archaeologists also unearthed a Roman staging post, or ''mansio''. The ancient building had been perfectly preserved over the course of the centuries by a heavy layer of desert sand. The team from Udine University made their discoveries during their tenth annual excavation in central Syria, which wrapped up at the end of November. The necropolis is the latest in a string of dazzling finds by the team. Efforts have chiefly focused on the ancient Syrian capital of Qatna, northeast of modern-day Homs. -

The Syrian Civil War Student Text

The Syrian Civil War Student Text PREVIEW Not for Distribution Copyright and Permissions This document is licensed for single-teacher use. The purchase of this curriculum unit includes permission to make copies of the Student Text and appropriate student handouts from the Teacher Resource Book for use in your own classroom. Duplication of this document for the purpose of resale or other distribution is prohibited. Permission is not granted to post this document for use online. Our Digital Editions are designed for this purpose. See www.choices.edu/digital for information and pricing. The Choices Program curriculum units are protected by copyright. If you would like to use material from a Choices unit in your own work, please contact us for permission. PREVIEWDistribution for Not Faculty Advisors Faculty at Brown University provided advice and carefully reviewed this curriculum. We wish to thank the following scholars for their invaluable input to this curriculum: Faiz Ahmed Meltem Toksöz Associate Professor of History, Department of History, Visiting Associate Professor, Middle East Studies and Brown University Department of History, Brown University Contributors The curriculum developers at the Choices Program write, edit, and produce Choices curricula. We would also like to thank the following people for their essential contributions to this curriculum: Noam Bizan Joseph Leidy Research and Editing Assistant Content Advisor Talia Brenner Gustaf Michaelsen Lead Author Cartographer Julia Gettle Aidan Wang Content Advisor Curriculum Assistant Front cover graphic includes images by Craig Jenkins (CC BY 2.0), Georgios Giannopoulos (Ggia) (CC BY-SA 4.0), and George Westmoreland. © Imperial WarPREVIEW Museums (Q 12366). -

Weekly Conflict Summary June 30 - July 6, 2016

Weekly Conflict Summary June 30 - July 6, 2016 The conflict events in Syria between 30 June - 6 July again focused primarily on the governorate of Aleppo, where about half of recorded instances of conflict occurred. Most conflict in the governorate happened in the cities of Menbij and Aleppo. On 6 July, the Syrian government announced a nationwide 72-hour ceasefire for Eid al-Fitr. Just hours after the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) declared a ceasefire for Eid al-Fitr, barrel bombs fell on Hureitan, north of Aleppo and pro-government forces have reportedly nearly captured the besieged town of Madaya in Rural Damascus. Government forces also continued their offensive to take control of Kastillo Road and surround the city of Aleppo, succeeding (as of July 7th) in closing the road and effectively besieging the opposition-controlled portion of Aleppo city. Pro-government forces are not, however, in full control of the area and heavy fighting continues with opposition reinforcements trying to push back recent gains. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) offensive for Menbij continues, with a few setbacks. ISIS has launched multiple attempts to break the siege, deploying suicide bombers to the northeast and west of the city to paralyze SDF frontlines. ISIS claims to have recaptured a handful of villages to the north and east of the city, reoccupying villages and hills in the surrounding area. SDF reports that about 600 ISIS fighters remain in Menbij, though this estimate has not been independently verified. On July 2, Jabhat al-Nusra fighters captured the leader of Jaysh al-Tahrir and about 40 of his fighters in Kafr Nobol in Idleb governorate.1 Jaysh al-Tahrir is backed by Western governments and thus joins a long list of similar groups that have been targeted by Jabhat al-Nusra.