Blue-Grey Taildropper Slug Prophysaon Coeruleum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Assessment for Cryptomastix Hendersoni

Conservation Assessment for Cryptomastix hendersoni, Columbia Oregonian Cryptomastix hendersoni, photograph by Bill Leonard, used with permission. Originally issued as Management Recommendations February 1999 by John S. Applegarth Revised Sept 2005 by Nancy Duncan Updated April 2015 By: Sarah Foltz Jordan & Scott Hoffman Black (Xerces Society) Reviewed by: Tom Burke USDA Forest Service Region 6 and USDI Bureau of Land Management, Oregon and Washington Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Cryptomastix hendersoni - Page 1 Preface Summary of 2015 update: The framework of the original document was reformatted to more closely conform to the standards for the Forest Service and BLM for Conservation Assessment development in Oregon and Washington. Additions to this version of the Assessment include NatureServe ranks, photographs of the species, and Oregon/Washington distribution maps based on the record database that was compiled/updated in 2014. Distribution, habitat, life history, taxonomic information, and other sections in the Assessment have been updated to reflect new data and information that has become available since earlier versions of this document were produced. A textual summary of records that have been gathered between 2005 and 2014 is provided, including number and location of new records, any noteworthy range extensions, and any new documentations on FS/BLM land units. A complete assessment of the species’ occurrence on Forest Service and BLM lands in Oregon and Washington is also provided, including relative abundance on each unit. Cryptomastix hendersoni - Page 2 Table of Contents Preface 1 Executive Summary 4 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 6 II. Classification and Description 7 A. -

Haida Gwaii Slug,Staala Gwaii

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Haida Gwaii Slug Staala gwaii in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2013 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2013. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Haida Gwaii Slug Staala gwaii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 44 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Kristiina Ovaska and Lennart Sopuck of Biolinx Environmental Research Inc., for writing the status report on Haida Gwaii Slug, Staala gwaii, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Dwayne Lepitzki, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Molluscs Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Limace de Haida Gwaii (Staala gwaii) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Haida Gwaii Slug — Photo by K. Ovaska. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2013. Catalogue No. CW69-14/673-2013E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-22432-9 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – May 2013 Common name Haida Gwaii Slug Scientific name Staala gwaii Status Special Concern Reason for designation This small slug is a relict of unglaciated refugia on Haida Gwaii and on the Brooks Peninsula of northwestern Vancouver Island. -

(Gastropoda: Eupulmonata: Onchidiidae) from Iran, Persian Gulf

Zootaxa 4758 (3): 501–531 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4758.3.5 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2F2B0734-03E2-4D94-A72D-9E43A132D1DE Description of a new Peronia species (Gastropoda: Eupulmonata: Onchidiidae) from Iran, Persian Gulf FATEMEH MANIEI1,3, MARIANNE ESPELAND1, MOHAMMAD MOVAHEDI2 & HEIKE WÄGELE1 1Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2Iranian Fisheries Science Research Institute (IFRO), 1588733111, Tehran, Iran. E-mail: [email protected] 3Corresponding author Abstract Peronia J. Fleming, 1822 is an eupulmonate slug genus with a wide distribution in the Indo-Pacific Ocean. Currently, nine species are considered as valid. However, molecular data indicate cryptic speciation and more species involved. Here, we present results on a new species found in the Persian Gulf, a subtropical region with harsh conditions such as elevated salinity and high temperature compared to the Indian Ocean. Peronia persiae sp. nov. is described based on molecular, histological, anatomical, micro-computer tomography and scanning electron microscopy data. ABGD, GMYC and bPTP analyses based on 16S rDNA and cytochrome oxidase I (COI) sequences of Peronia confirm the delimitation of the new species. Moreover, our 14 specimens were carefully compared with available information of other described Peronia species. Peronia persiae sp. nov. is distinct in a combination of characters, including differences in the genital (ampulla, prostate, penial hooks, penial needle) and digestive systems (lack of pharyngeal wall teeth, tooth shape in radula, intestine of type II). -

Interior Columbia Basin Mollusk Species of Special Concern

Deixis l-4 consultants INTERIOR COLUMl3lA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN cryptomasfix magnidenfata (Pilsbly, 1940), x7.5 FINAL REPORT Contract #43-OEOO-4-9112 Prepared for: INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECT 112 East Poplar Street Walla Walla, WA 99362 TERRENCE J. FREST EDWARD J. JOHANNES January 15, 1995 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 ‘(206) 527-6764 INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN Terrence J. Frest & Edward J. Johannes Deixis Consultants 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 (206) 527-6764 January 15,1995 i Each shell, each crawling insect holds a rank important in the plan of Him who framed This scale of beings; holds a rank, which lost Would break the chain and leave behind a gap Which Nature’s self wcuid rue. -Stiiiingfieet, quoted in Tryon (1882) The fast word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: “what good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. if the biota in the course of eons has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first rule of intelligent tinkering. -Aido Leopold Put the information you have uncovered to beneficial use. -Anonymous: fortune cookie from China Garden restaurant, Seattle, WA in this “business first” society that we have developed (and that we maintain), the promulgators and pragmatic apologists who favor a “single crop” approach, to enable a continuous “harvest” from the natural system that we have decimated in the name of profits, jobs, etc., are fairfy easy to find. -

Soil Calcium Availability Influences Shell Ecophenotype Formation in the Sub-Antarctic Land Snail, Notodiscus Hookeri

Soil Calcium Availability Influences Shell Ecophenotype Formation in the Sub-Antarctic Land Snail, Notodiscus hookeri Maryvonne Charrier1*, Arul Marie2, Damien Guillaume3, Laurent Bédouet4, Joseph Le Lannic5, Claire Roiland6, Sophie Berland4, Jean-Sébastien Pierre1, Marie Le Floch6, Yves Frenot7, Marc Lebouvier8 1 Université de Rennes 1, Université Européenne de Bretagne, UMR CNRS 6553, Campus de Beaulieu, Rennes, France, 2 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Plateforme de Spectrométrie de Masse et de Protéomique, UMR CNRS 7245, Département Régulation Développement et Diversité Moléculaire, Paris, France, 3 Université de Toulouse, Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées, Géosciences Environnement Toulouse, UMR 5563 (CNRS/UPS/IRD/CNES), Toulouse, France., 4 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Biologie des Organismes et Ecosystèmes Aquatiques, UMR CNRS 7208 / IRD 207, Paris, France, 5 Université de Rennes 1, Université Européenne de Bretagne, Service Commun de Microscopie Electronique à Balayage et micro-Analyse, Rennes, France, 6 Université de Rennes 1, Université Européenne de Bretagne, Sciences Chimiques de Rennes, UMR CNRS 6226, Campus de Beaulieu, Rennes, France, 7 Institut Polaire Français Paul Émile Victor, Technopôle Brest-Iroise, Plouzané, France, 8 Université de Rennes 1, Université Européenne de Bretagne, UMR CNRS 6553, Station Biologique, Paimpont, France Abstract Ecophenotypes reflect local matches between organisms and their environment, and show plasticity across generations in response to current living conditions. Plastic responses in shell morphology and shell growth have been widely studied in gastropods and are often related to environmental calcium availability, which influences shell biomineralisation. To date, all of these studies have overlooked micro-scale structure of the shell, in addition to how it is related to species responses in the context of environmental pressure. -

The Slugs of Bulgaria (Arionidae, Milacidae, Agriolimacidae

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK INSTYTUT ZOOLOGII ANNALES ZOOLOGICI Tom 37 Warszawa, 20 X 1983 Nr 3 A n d rzej W ik t o r The slugs of Bulgaria (A rionidae , M ilacidae, Limacidae, Agriolimacidae — G astropoda , Stylommatophora) [With 118 text-figures and 31 maps] Abstract. All previously known Bulgarian slugs from the Arionidae, Milacidae, Limacidae and Agriolimacidae families have been discussed in this paper. It is based on many years of individual field research, examination of all accessible private and museum collections as well as on critical analysis of the published data. The taxa from families to species are sup plied with synonymy, descriptions of external morphology, anatomy, bionomics, distribution and all records from Bulgaria. It also includes the original key to all species. The illustrative material comprises 118 drawings, including 116 made by the author, and maps of localities on UTM grid. The occurrence of 37 slug species was ascertained, including 1 species (Tandonia pirinia- na) which is quite new for scientists. The occurrence of other 4 species known from publications could not bo established. Basing on the variety of slug fauna two zoogeographical limits were indicated. One separating the Stara Pianina Mountains from south-western massifs (Pirin, Rila, Rodopi, Vitosha. Mountains), the other running across the range of Stara Pianina in the^area of Shipka pass. INTRODUCTION Like other Balkan countries, Bulgaria is an area of Palearctic especially interesting in respect to malacofauna. So far little investigation has been carried out on molluscs of that country and very few papers on slugs (mostly contributions) were published. The papers by B a b o r (1898) and J u r in ić (1906) are the oldest ones. -

On the Distribution and Food Preferences of Arion Subfuscus (Draparnaud, 1805)

Vol. 16(2): 61–67 ON THE DISTRIBUTION AND FOOD PREFERENCES OF ARION SUBFUSCUS (DRAPARNAUD, 1805) JAN KOZ£OWSKI Institute of Plant Protection, National Research Institute, W³adys³awa Wêgorka 20, 60-318 Poznañ, Poland (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: In recent years Arion subfuscus (Drap.) is increasingly often observed in agricultural crops. Its abun- dance and effect on winter oilseed rape crops were studied. Its abundance was found to be much lower than that of Deroceras reticulatum (O. F. Müll.). Preferences of A. subfuscus to oilseed rape and 19 other herbaceous plants were determined based on multiple choice tests in the laboratory. Indices of acceptance (A.I.), palat- ability (P.I.) and consumption (C.I.) were calculated for the studied plant species; accepted and not accepted plant species were identified. A. subfuscus was found to prefer seedlings of Brassica napus, while Chelidonium maius, Euphorbia helioscopia and Plantago lanceolata were not accepted. KEY WORDS: Arion subfuscus, abundance, oilseed rape seedlings, herbaceous plants, acceptance of plants INTRODUCTION Pulmonate slugs are seroius pests of plants culti- common (RIEDEL 1988, WIKTOR 2004). It lives in low- vated in Poland and in other parts of western and cen- land and montane forests, shrubs, on meadows, tral Europe (GLEN et al. 1993, MESCH 1996, FRANK montane glades and sometimes even in peat bogs. Re- 1998, MOENS &GLEN 2002, PORT &ESTER 2002, cently it has been observed to occur synanthropically KOZ£OWSKI 2003). The most important pest species in such habitats as ruins, parks, cemeteries, gardens include Deroceras reticulatum (O. F. Müller, 1774), and and margins of cultivated fields. -

BRYOLOGICAL INTERACTION-Chapter 4-6

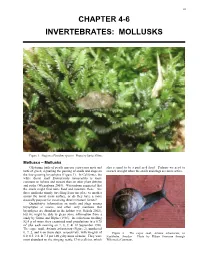

65 CHAPTER 4-6 INVERTEBRATES: MOLLUSKS Figure 1. Slug on a Fissidens species. Photo by Janice Glime. Mollusca – Mollusks Glistening trails of pearly mucous criss-cross mats and also seemed to be a preferred food. Perhaps we need to turfs of green, signalling the passing of snails and slugs on searach at night when the snails and slugs are more active. the low-growing bryophytes (Figure 1). In California, the white desert snail Eremarionta immaculata is more common on lichens and mosses than on other plant detritus and rocks (Wiesenborn 2003). Wiesenborn suggested that the snails might find more food and moisture there. Are these mollusks simply travelling from one place to another across the moist moss surface, or do they have a more dastardly purpose for traversing these miniature forests? Quantitative information on snails and slugs among bryophytes is scarce, and often only mentions that bryophytes are abundant in the habitat (e.g. Nekola 2002), but we might be able to glean some information from a study by Grime and Blythe (1969). In collections totalling 82.4 g of moss, they examined snail populations in a 0.75 m2 plot each morning on 7, 8, 9, & 12 September 1966. The copse snail, Arianta arbustorum (Figure 2), numbered 0, 7, 2, and 6 on those days, respectively, with weights of Figure 2. The copse snail, Arianta arbustorum, in 0.0, 8.5, 2.4, & 7.3 per 100 g dry mass of moss. They were Stockholm, Sweden. Photo by Håkan Svensson through most abundant on the stinging nettle, Urtica dioica, which Wikimedia Commons. -

The Ecology of Mitcham Common 1984 Report

THE ECOLOGY OF MITCHAM COMMON THE(A ECOLOGY report on the statusOF MITCHAM of the flora and COMMON fauna) The final report of the "Ecological Survey of Mitcham Common" Supervised by: R.K.A. Morris BSc. FRES Participating authors: R.D. Dunn BSc. A.M. Harvey BSc. J.A. Hollier BSc. ARCS. FRES. C.M. Johnstone Cert. Ecol. Cons. A.D. Sclater BSc. FRES. C. Wilson BSc. Funded by: The Manpower Services Commission Administered by: Merton Community Programme Agency Sponsored by: The Mitcham Common Conservators and the London Borough of Merton Department of Recreation and Arts Report completed and submitted: September 1984. Crown Copyright. Cover photograph: Seven Islands Pond from Mill Hill, September 1974 (Photo Dr P.G. Morris) iv 2016 version This report was produced by a team of recent graduates, employed under the 'Community Programme' and funded by the Manpower Services Commission. The objectives of the Programme were to provide the long-term unemployed with opportunities to train or re- train, so that they might get more permanent work. This Programme funded a considerable number of environmental jobs, and provided the stepping stone for many ecologists to move into mainstream jobs. I have lost contact with most of the team members of this project, but am aware that at least one (apart from me) went onto a successful career in an ecological discipline. Looking back to the year of 1983-84, it is difficult to appreciate the achievement of the team. We commenced work in September 1983 and were due to report in late August 1984. The timing was unfortunate because we were unable to make best use of the year, with the winter occupying most of the project. -

Fauna of New Zealand Ko Te Aitanga Pepeke O Aotearoa

aua o ew eaa Ko te Aiaga eeke o Aoeaoa IEEAE SYSEMAICS AISOY GOU EESEAIES O ACAE ESEAC ema acae eseac ico Agicuue & Sciece Cee P O o 9 ico ew eaa K Cosy a M-C aiièe acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa EESEAIE O UIESIIES M Emeso eame o Eomoogy & Aima Ecoogy PO o ico Uiesiy ew eaa EESEAIE O MUSEUMS M ama aua Eiome eame Museum o ew eaa e aa ogaewa O o 7 Weigo ew eaa EESEAIE O OESEAS ISIUIOS awece CSIO iisio o Eomoogy GO o 17 Caea Ciy AC 1 Ausaia SEIES EIO AUA O EW EAA M C ua (ecease ue 199 acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 38 Naturalised terrestrial Stylommatophora (Mousca Gasooa Gay M ake acae eseac iae ag 317 amio ew eaa 4 Maaaki Whenua Ρ Ε S S ico Caeuy ew eaa 1999 Coyig © acae eseac ew eaa 1999 o a o is wok coee y coyig may e eouce o coie i ay om o y ay meas (gaic eecoic o mecaica icuig oocoyig ecoig aig iomaio eiea sysems o oewise wiou e wie emissio o e uise Caaoguig i uicaio AKE G Μ (Gay Micae 195— auase eesia Syommaooa (Mousca Gasooa / G Μ ake — ico Caeuy Maaaki Weua ess 1999 (aua o ew eaa ISS 111-533 ; o 3 IS -7-93-5 I ie 11 Seies UC 593(931 eae o uIicaio y e seies eio (a comee y eo Cosy usig comue-ase e ocessig ayou scaig a iig a acae eseac M Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Māoi summay e y aco uaau Cosuas Weigo uise y Maaaki Weua ess acae eseac O o ico Caeuy Wesie //wwwmwessco/ ie y G i Weigo o coe eoceas eicuaum (ue a eigo oaa (owe (IIusao G M ake oucio o e coou Iaes was ue y e ew eaIa oey oa ue oeies eseac -

The Physical Properties of the Pedal Mucus of the Terrestrial Slug, Ariolimax Columbianus

J. exp. Biol. (1980), 88, 375-393 375 With 15 figures ^Printed in Great Britain THE PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF THE PEDAL MUCUS OF THE TERRESTRIAL SLUG, ARIOLIMAX COLUMBIANUS BY MARK W. DENNY* AND JOHN M. GOSLINE Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, V6T 1W5 (Received 8 May 1980) SUMMARY The pedal mucus of gastropods functions in locomotion by coupling the movements of the foot to the substratum. The pedal mucus of the terrestrial slug, Ariolimax columbianus, is suited to this role by the following unusual physical properties. 1. At small deformations the mucus is a viscoelastic solid with a shear modulus of 100-300 Pa. 2. The mucus shows a sharp yield point at a strain of 5-6, the yield stress increasing with increasing strain rate. 3. At strains greater than 6 the mucus is a viscous liquid (rj = 30-50 poise). 4. The mucus recovers its solidity if allowed to ' heal' for a period of time, the amount of solidity recovered increasing with increasing time. INTRODUCTION The ventral surface of a gastropod's foot is separated from the sub-stratum by a thin layer of mucus. In many cases this mucus layer is left behind as the animal crawls, forming the slime trail that is characteristic of terrestrial snails and slugs. The importance of this pedal mucus in the locomotion and adhesion of gastropods has been known for a considerable time. Barr (1926) reports that slugs deprived of pedal mucus by cauterizing the suprapedal mucus gland can neither crawl nor adhere. Later authors (Lissman, 1945; Jones, 1973, 1975; Miller, 1974) speculate that pedal mucus serves as an adhesive in all gastropods, coupling the force of foot movements to the substratum. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Patellogastropoda (Mollusca: Gastropoda)

^03 Marine Biology (2000) 137: 183-194 ® Spnnger-Verlag 2000 M. G. Harasevvych A. G. McArthur A molecular phylogeny of the Patellogastropoda (Mollusca: Gastropoda) Received: 5 February 1999 /Accepted: 16 May 2000 Abstract Phylogenetic analyses of partiaJ J8S rDNA formia" than between the Patellogastropoda and sequences from species representing all living families of Orthogastropoda. Partial 18S sequences support the the order Patellogastropoda, most other major gastro- inclusion of the family Neolepetopsidae within the su- pod groups (Cocculiniformia, Neritopsma, Vetigastro- perfamily Acmaeoidea, and refute its previously hy- poda, Caenogastropoda, Heterobranchia, but not pothesized position as sister group to the remaining Neomphalina), and two additional classes of the phylum living Patellogastropoda. This region of the Í8S rDNA Mollusca (Cephalopoda, Polyplacophora) confirm that gene diverges at widely differing rates, spanning an order Patellogastropoda comprises a robust clade with high of magnitude among patellogastropod lineages, and statistical support. The sequences are characterized by therefore does not provide meaningful resolution of the the presence of several insertions and deletions that are relationships among higher taxa of patellogastropods. unique to, and ubiquitous among, patellogastropods. Data from one or more genes that evolve more uni- However, this portion of the 18S gene is insufficiently formly and more rapidly than the ISSrDNA gene informative to provide robust support for the mono- (possibly one or more