THE BIG CHUNK of ICE: Another Adventure of the Mad Scientists of Mammoth Falls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

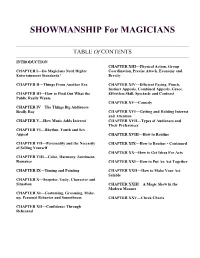

SHOWMANSHIP for MAGICIANS

SHOWMANSHIP For MAGICIANS TABLE Of CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER XIII—Physical Action, Group CHAPTER I—Do Magicians Need Higher Coordination, Precise Attack, Economy and Entertainment Standards? Brevity CHAPTER II—Things From Another Era CHAPTER XIV—Efficient Pacing, Punch, Instinct Appeals, Combined Appeals, Grace, CHAPTER III—How to Find Out What the Effortless Skill, Spectacle and Contrast Public Really Wants CHAPTER XV—Comedy CHAPTER IV—The Things Big Audiences Really Buy CHAPTER XVI—Getting and Holding Interest and Attention CHAPTER V—How Music Adds Interest CHAPTER XVII—Types of Audiences and Their Preferences CHAPTER VI—Rhythm, Youth and Sex Appeal CHAPTER XVIII—How to Routine CHAPTER VII—Personality and the Necessity CHAPTER XIX—How to Routine - Continued of Selling Yourself CHAPTER XX—How to Get Ideas For Acts CHAPTER VIII—Color, Harmony, Sentiment, Romance CHAPTER XXI—How to Put An Act Together CHAPTER IX—Timing and Pointing CHAPTER XXII—How to Make Your Act Salable CHAPTER X—Surprise, Unity, Character and Situation CHAPTER XXIII—A Magic Show in the Modern Manner CHAPTER XI—Costuming, Grooming, Make- up, Personal Behavior and Smoothness CHAPTER XXV—Check Charts CHAPTER XII—Confidence Through Rehearsal INTRODUCTION The fact that I feel there to be a definite need for this book is evidenced by my having written it. While this work is intended primarily for magicians, there is very much here, particularly the analysis of audience preferences and appeals, which applies to entertainers generally. There is a right way and a wrong way of doing anything. But the right way of yesterday is not necessarily the right way of today. -

Cinéma, De Notre Temps

PROFIL Cinéma, de notre Temps Une collection dirigée par Janine Bazin et André S. Labarthe John Ford et Alfred Hitchcock Le loup et l’agneau le 4 juillet 2001 Danièle Huillet et Jean-Marie Straub le 11 juillet 2001 Aki Kaurismäki le 18 juillet 2001 Georges Franju, le visionnaire le 25 juillet 2001 Rome brûlée, portrait de Shirley Clarke le 1er août 2001 Akerman autoportrait le 8 août 2001 23.15 tous les mercredis du 4 juillet au 8 août Contact presse : Céline Chevalier / Nadia Refsi - 01 55 00 70 41 / 70 40 [email protected] / [email protected] La collection Cinéma, de notre temps Cinéma, de notre temps, collection deux fois née*, c'est tout le contraire d'un pèlerinage à Hollywood, " cette marchande de coups de re v o l v e r et (…) de tout ce qui fait circuler le sang ". C'est la tentative obstinée d'éclairer et de montre r, dans chacun des films qui la composent, comment le cinéma est bien l'art de notre temps et combien il est, à ce titre, redevable de bien autre chose que de réponses mondaines, de commentaires savants ou de célébrations. La programmation de cette collection est l'occasion de de constater combien ces " œuvres de télévision " échappent aux outrages du temps et constituent une constellation unique au monde dans le ciel du 7è m e a rt . Thierry Garrel Directeur de l'Unité de Programmes Documentaires à ARTE France *En 1964, Janine Bazin et André S Labarthe créent Cinéastes de notre temps. -

Houlton Times, June 22, 1921

Camping, Fishing and the Roads Were Never Better in Aroostook Than N ow -Com P m A ^ Z jT SHIRE TOWN OF AROOSTOOK TIMES AROOSTOOK COUNT) April 13, 1860 To BOULTON TIMES December 27, 19l6 VOL. LX I HOULTON, MAINE, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22, U)21 No. 25 STRONG-HUSSEY ODD FELLOWS The home of Mr. and Mrs. Benj. ANDERSON-OLIVER T. Hussey on the Ludlow road was FIELD DAY OF AROOSTOOK At 12 o'clock at the home of Mr. the scene of a very pretty wedding Miles MeElwee on Green street. H0LSTE1NFR1ESIAN JNTERTAIN June 15th, at 4 o’clock, when their Afliyln, (laughter of Mrs. Jennie Oliver J daughter Viola M. was married to was uni:ed in marriage to I)onald | HELD DAY HELD ! Cecil H. Strong. Rev. A. M. Thomp- TELEPHONE COMPANY Anderson, son of Mr. and Mrs. C. M. j -------- - Vistfng Degree Teams Work j son, pastor of the Congregational Anderson of North street, by Rev. A f Q P If ■ | church performed the single ring Henry Speed, pastor of the Baptist ; I/WIICF Of uU IM nil f 31*111 llO S t Two Degrees j ceremony before the immediate rela- Business and Pleasure Combined Make the Day One Long church, who performed the single j tives. / j ring service. to Farmers The long looked for event in Odd The bridal party stood under an to be Remembered The bride wore a blue traveling suit _____ Fellows circles, the Dirtrict meeting arch of cedar and white roses. The with hat to match and wore a corsage j That the Field Day of the Encampment branch of the bride wore a navy blue suit, black The second annual Field Day of Powers, Directors Simon Friedman, boqu<>t wt white roses and sweet peas. -

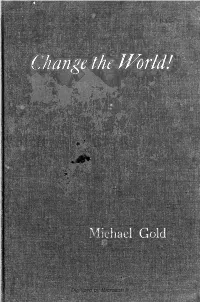

Goldchangetheworld36.Pdf

/, From the collection of the n z m o Prelinger i a v JJibrary San Francisco, California 2006 CHANGE THE WORLD! Change the World! Michael Gold FOREWORD BY ROBERT FORSYTHE INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS NEW YORK COPYRIGHT, 1936, BY INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS CO., INC ACKNOWLEDGMENT Most these selections of were -first pub- lished as columns in the Daily Worker. Others are reprinted from the New Masses. "Mussolini's Nightmare" is from Anvil. PRINTED IN THB U. 8. A. UNION LABOR THROUGHOUT Designed by Robert Joepky CONTENTS FOREWORD, BY ROBERT FORSYTHE 7 MUSSOLINI'S NIGHTMARE 11 HOW THEY PICKED A HERO 16 A LOVE NOTE FROM THE K.K.K. 19 GERTRUDE STEIN! A LITERARY IDIOT 23 MR. BOOLEY AND THE PIGEONS 27 ANGELO HERNDON GOES TO THE CHAIN GANG 31 NEW ESCAPES FROM THE SOVIETS 35 THE MIDDLE CLASS AND WAR 39 A NIGHT IN THE MILLION DOLLAR SLUMS 45 THE GUN IS LOADED, DREISER! 50 THE FABLE OF THE IDEAL GADGET 60 DEATH OF A GANGSTER 64 THE HAUNTED FIREHOUSE 67 HE WAS A MAN 71 ANOTHER SUICIDE 75 FREMONT OLDER: LAST OF THE BUFFALOES 78 A SAMSON OF THE BRONX 84 HELL IN A DRUGSTORE 88 ART YOUNG : ONE-MAN UNITED FRONT 91 THE MINERS OF PECS 94 BASEBALL IS A RACKET 98 A CONVERSATION IN OUR TIME 101 AT A MINER'S WEDDING 105 THAT MOSCOW GOLD AGAIN 109 PASSION AND DEATH OF VAN GOGH 113 NIGHT IN A HOOVERVILLE 115 FOR A NEW WORLD FAIR 120 SORROWS OF A SCAB 123 5 IN A HOME RELIEF STATION 127 THEY REFUSE TO SHARE THE GUILT 130 CAN A SUBWAY BE BEAUTIFUL? 133 HOMAGE TO AN OLD HOUSE PAINTER 136 THE WORLD OF DREAMS 139 BARNYARD POET 143 THE HEARSTS OF 1776 147 DOWN WITH THE SKYSCRAPERS! -

John Ford Birth Name: John Martin Feeney (Sean Aloysius O'fearna)

John Ford Birth Name: John Martin Feeney (Sean Aloysius O'Fearna) Director, Producer Birth Feb 1, 1895 (Cape Elizabeth, ME) Death Aug 31, 1973 (Palm Desert, CA) Genres Drama, Western, Romance, Comedy Maine-born John Ford originally went to Hollywood in the shadow of his older brother, Francis, an actor/writer/director who had worked on Broadway. Originally a laborer, propman's assistant, and occasional stuntman for his brother, he rose to became an assistant director and supporting actor before turning to directing in 1917. Ford became best known for his Westerns, of which he made dozens through the 1920s, but he didn't achieve status as a major director until the mid-'30s, when his films for RKO (The Lost Patrol [1934], The Informer [1935]), 20th Century Fox (Young Mr. Lincoln [1939], The Grapes of Wrath [1940]), and Walter Wanger (Stagecoach [1939]), won over the public, the critics, and earned various Oscars and Academy nominations. His 1940s films included one military-produced documentary co-directed by Ford and cinematographer Gregg Toland, December 7th (1943), which creaks badly today (especially compared with Frank Capra's Why We Fight series); a major war film (They Were Expendable [1945]); the historically-based drama My Darling Clementine (1946); and the "cavalry trilogy" of Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950), each of which starred John Wayne. My Darling Clementine and the cavalry trilogy contain some of the most powerful images of the American West ever shot, and are considered definitive examples of the Western. Ford also had a weakness for Irish and Gaelic subject matter, in which a great degree of sentimentality was evident, most notably How Green Was My Valley (1941) and The Quiet Man (1952), which was his most personal film, and one of his most popular. -

American Cinematographer (1922)

— — Announcement We TAKE great pride in announcing the fact that each day finds us doing something new—doing something no other laboratory has done before—improving upon old processes, perfecting new ones and above all, actually giving our clientele the utmost perfection in laboratory work. OlJR Experimental Laboratory, maintained solely for your benefit, is prepared at all times to assist you in the solution of many difficult problems and its co-operation is offered you gratis. W HEN we say that every department of our laboratory is in charge of an expert we are not merely "stating" something because it seems the customary thing to do. We say it because it is true and invite your thorough investigation. What do you think about this? Is IT worth your while to try a laboratory that not only has high ideals of workmanship, but inflexibly maintains them? The Kosmos Laboratories are under the personal supervision of Doctor Elmore R. Walters. Kosmos Film Laboratories llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllll II I II II I I I.IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIHIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII1IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII»^ DEVELOPING — PRINTING — TITLES Specializing in Color Work SINGLE, DOUBLE and TRIPLE TONES 22 Different Tints 4811 FOUNTAIN AVENUE Phone Hollywood 3266 Los Angeles, Cal. Vol. 2 February 1, 1922 No. 26 The American Cinematographer The Voice of the Motion Picture Cameramen of America; the men who make the pictures SILAS E. SNYDER, Editor Associate Editors—ALVIN WYCKOFF, H. LYMAN BROENING, KARL BROWN, PHILIP H. WHITMAN An educational and instructive publication espousing progress and art in motion picture pho- tography while fostering the industry We cordially invite news articles along instructive and constructive lines of motion picture photography from our members and directors active in the motion picture industry. -

Sangre Fácil

PROJECCIÓ 167 Antiga Audiència, dimarts 11 de març de 2003 Las uvas de la ira The Grapes of Wrath, John Ford, 1940 Aquest film és el relat més impressionant sobre la depressió que hi va haver a Estats Units durant els anys 30. Tota una crida a la solidaritat. A Las uvas de la ira una família de grangers intenta És un dels sis pilars del temple Hollywood, un Fitxa tècnica sobreviure a l’Amèrica de la gran depressió, després de d’aquells homes que va modelar el rostre del que els hagin expropiat les terres. Amb un vell camió cinema. Fitxa tècnica recorreran tot l’Estat a la cerca de terres on puguin Realitzador: John Ford La simplicitat és una de les virtuts predominants a treballar com a jornalers. La seva situació és crítica, ja que Productor: Darryl F.Zanuck les 140 pel·lícules que va rodar entre el 1917 i el no hi ha feina i són molts els qui es troben en la mateixa Muntatge: Gregg Toland 1966, tot un exemple de direcció d’actors. situació. Guió: John Steinbeck i Nunally Johnson Simplicitat d’una acció concentrada i depurada Fotografia: Gregg Toland Aquest film, basat en la novel·la de John fins a la perfecció, digna de tots els elogis dels Música: Alfred Newman Steinbeck és, fonamentalment, una dura crítica al cineastes, crítics i públic de tot el món. La carrera Companyia productora: Twentieth Century Fox somni americà que tant ens volen vendre. Ens de John Ford es podria dividir en quatre períodes: Nacionalitat: Estats Units mostra la vertadera realitat d’una època de L’època muda (1917-1928). -

British Ship Losses Cut by Two-Thirds

Average Daily Clrculatfen Far the Month of Angnst, 1P4I 6,762 Member of the Andit Oeoaaioaal Ught rata taalght a a i Boraon af Clrenlatlou Wedaeaday; wanner toalght: viaw- ly rlalag temperatore n ’rhridaj Manchester— City of Village Charm l ■ VOL. LX ., NO. 308 (Claaaiaed Advertialog On Page 12) MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1941 (FOURTEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CE Wreck of Swiss Freight Train Laid to Land Mines Roosevelt and Hull British Ship Losses Confer on Change Cut by Two-Thirds; In Neutrality Law m Talk on All Phrases of Rescue Man Raid International S i t ii a • Gern lan Cities tion; Secretary Re During Fire fuses to Tell of Any Hamburg and Stettin At Britain Seizes Initiative tacked in Their Heav War A treacly Specific Recommenda At Bristol In Air and Has Sev» iest Bombing of War tions on Arming Ships. Faces Nation eral Times Considered^ In Overnight Raids of W'ashington, Sept. 30.—(/P) T' Others Cratcl Down Invasion of German- Hundreds of Planes; —For an hour and 45 min Ladders While Blaxe\ T Bar Is Told Dominated Continentg utes, President Roosevelt aijd ‘.Many I^arge Fires’ Set Sweeps Gridley Ho-' (.hurrhill Tells Com- Secretary of State Hull con On Dorks, Railway Hyan Asserts Germany mons in Optimistic ferred on all phases of the tef; Loss $200,000. international situation today, Station in Stettin. Has Started Hdstili. War Review Today. presumably with emphasis on Bristol, Sept. 30.—(/P)_One pei^ London, Sept. 30.—(/P>__ tie*; Gommerce on son was rescued by firemen, two revision of the neutrality law. -

ES12.2.1948.Pdf

HAIL C. I. T. Words and Music by MANTON M. BARNES'n. .... Esprissavo . .... t: .. ... .. .. .. -G .. ... .. • .. In South· erft Cal • , • for - nia With grace and splen· dor bound- ... ,.. ~ . - I I I I l' I ,. ,.. - ... .,. .. .. .. ~ ..... ..... .. Where the loft - y moun-tain peaks Look out to lands be - yond. Proud -Iy stands our a" .. ., a .. h. • • I , II' I ~ I I " ( " -4 111 ... ... • .. .. \01'"", I I Al - I'M Ma· ter Glo - ri·ous to see. yoafse ollr Yoi - ces h~iI - lng. , . :t J J I I I -J ~' I I' J I I I ~ I ~ I I I ... • • ~ . • ,. --' ... -G -6 W" U Q'" • .. .. .hail- ing. hail-Ing thee:- Eeh·oes ring-ing while we're slng-ing 0- ver land and • fh'] - - • \ , . J--i I I If I .... !' I I .. 1 t., v'" , If .... ... ... ... ... - '\Ii' sea; The hans of fame re-sound thy name No • ble C. t. T. ( 1 a. -tr ., . ~ Copyrlsht HCM.X.IX b~ Manton K. Barnes IN THIS ISSUE A non-alumnus is responsible for the publication of Hail CI.T. (across the page) in this issue of E &: S. By some devious means this gentle man had crashed the gate at a recent alumni function and was quietly play ing the piano when the crowd bore down on him and called for Hail CLT. The pianist was agreeable enough, but asked for a copy of the r u f S h a /I You F r e e sheet music. This proved to be an The T h impossible request, and, while the pianist learned to play the song by ear, the search he started went on for several days. -

Overview of Newspaper Article Summaries

Overview of Newspaper Article Summaries Billings Gazette – Billings, MT: Summary and Articles from 08/18/1959 to 08/28/1959 Bozeman Daily Chronicle – Bozeman, MT: Summary and Articles from 08/18/1959 to 10/24/1935 Summary and Articles from 10/21/1964 to 10/23/1964 Deseret News – Salt Lake City, UT: Summary and Articles from 08/18/1959 to 08/24/1959 Montana Standard – Butte, MT: Summary and Articles from 08/18/1959 to 08/25/1959 Salt Lake Tribune – Salt Lake City, UT: Summary and Articles from 08/18/1959 to 08/23/1959 Summary of Newspaper Articles Back to Overview Billings Gazette – Billings, MT (last date searched 08/28/1959) Headline: Billings Rocked By Sharp Quake; Entire Northwest Area Is Reported Jolted Date: 08/18/1959 Info Categories: E, H, N, P Headline: West Yellowstone Entrance, Norris Cutoff Road Closed Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: B, G, I, L, P Headline: Park's Heaviest Quake Damage At Old Faithful Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: B, G, H, I, L, P Headline: Billings Matron Victim Of Quake Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: A, E, I, L, N, P Headline: Local Photographer Reports Temblor Cracked Mountains Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: A, G, I, L, P Headline: Billings Father Sights Son, Friends Safe In Quake Area Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: A, B, G, L, N, P Headline: Flies Over Area Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: A, G, L, P Headline: Anacondan Tells Of Discovering Woman Who Survived Slide Horror Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: A, G, P Headline: Citadel Aid Goes To Stricken Area Date: 08/19/1959 Info Categories: -

Nigeria in the Ring: Boxing, Masculinity, and Empire in Nigeria, 1930-1957

NIGERIA IN THE RING: BOXING, MASCULINITY, AND EMPIRE IN NIGERIA, 1930-1957 By MICHAEL GENNARO A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Michael Gennaro To my parents, both Northern and Southern – whom I am sure never thought in their wildest dreams they would have a child teach them so much about boxing in Nigeria. To them I owe my love of sports, history, pasta, and learning. Keep on Loving ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Since I started this dissertation project, I have been asked, for what feels like a million times, the same question (with all its variants) by all who hear about the topic of boxing in Nigeria: “are you yourself a boxer?” As a male, 6’1,” and 230 lbs., the question seems like the most obvious one to ask. Although I have never laced up the gloves and stepped into the ring, this dissertation and Ph.D. about boxing was, to me, very similar to a boxing career: one could say it resembles the buildup, preparation, training, rising up the rankings, and, ultimately, a championship boxing match. It required years of training, long hours away from family and friends, heartache, pain, disappointment, and in the end, success. In that way, let me both explain my road to this point, acknowledge those that helped me in some way towards my big fight for the dissertation and Ph.D. “title.” Without the help, support, and love of so many, my training would have been in vain. -

Ficha Técnica

EL CABALLO DE HIERRO FICHA TÉCNICA Director John Ford Guión Charles Kenyon y John Russell Producción William Fox Productor John Ford Fotografía George Schneiderman y George Guffey Música Adaptación de Christopher Caliendo DATOS TÉCNICOS Título original The Iron Horse Género Western Versión Muda, con subtítulos en castellano Duración 130 minutos Año de producción 1924, EE.UU: Formato 35 mm. 1:1,33. Blanco y negro Estreno 28/08/1924, en EE.UU. Localizaciones Beale’s Cut, Newhall (California); Chatsworth, Los Ángeles (California); Dodge Flat, Wadsworth (Nevada); Truckee (California) Distribución DVD Fox . FICHA ARTISTICA Intérpretes Personajes George O’Brien Davy Brandon Magde Bellamy Miriam Marsh Cyril Chadwick Peter Jesson Fred Kholer Bauman Gladys Hulette Rubi James Marcus Juez Haller James Welch Schultz J. Farrell MacDonald Cpl. Casey Walter Rogers El General Dodge Carlos Eduardo Toro Abraham Lincoln Francis Power Sargento Slattery George Waggner William Cody “Buffalo Bill” PRESENTACIÓN El presidente Lincoln ha autorizado la construcción de un enlace entre las líneas ferroviarias de la Union Pacific y la Central Pacific. Un contratista (Will Walling) y un topógrafo (George O'Brien) emprenden un viaje con el objetivo de trazar la ruta idónea, sin embargo, aunque consiguen localizar un paso montañoso que permitiría el establecimiento de una conexión mucho más rápida de lo que se había esperado, el riesgo de que los nativos ataquen a los trabajadores amenaza de estropear el ambicioso proyecto. Davy Brandon trabaja en las obras de la línea del ferrocarril transcontinental, entre 1863 y 1869, y se enamora de la hija del ingeniero ninguno, Miriam. Durante un topetazo con los indios descubre al guerrero manco que asesinó tiempo atrás a su padre.