The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 11 23 Aug , 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mixed Martial Arts

BAB II. REWA FIGHT GYM DAN MIXED MARTIAL ARTS II.1 Pengertian MMA MMA (Mixed Martial Arts) adalah olahraga beladiri campuran yang menggabungkan teknik memukul, menendang, membanting dan mengunci dari beberapa jenis bela diri. MMA Dipromosikan oleh kompetisi global yakni Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) pada tahun 1993, yang dikembangakan oleh Rorion Gracie, John Millius, dan Art Davie. Jenis beladiri yang sering digunakan dalam MMA contohnya Kickoxing, muay thai, karate, taekwondo, judo, jujitsu dan Wrestling. Hal yang menjadi identitas MMA yakni keunggulan teknik beladiri yang rumit untuk melumpuhkan lawan. (sumber: tribunnewswiki.com diakses tanggal 05/12/2020) Gambar II.1.1 Beladiri MMA Sumber: arsip Indosport (diakses pada tanggal 30/042020) II.2 Sejarah MMA MMA sebagai olah raga modern berhubungan dengan sejarah kemunculan kompetisi beladiri, salah satunya adalah UFC. Ultimate Fighting Championship ( UFC ) adalah perusahaan promosi seni bela diri campuran Amerika (MMA) yang berpusat di Las Vegas, Nevada , yang dimiliki dan dioperasikan oleh perusahaan induk William Morris Endeavour . Ini adalah perusahaan promosi MMA terbesar di dunia dan menampilkan beberapa petarung tingkat tertinggi dalam olahraga ini dalam daftar tersebut. UFC memproduksi acara di seluruh dunia yang menampilkan dua belas divisi berat (delapan divisi pria dan empat divisi wanita) dan mematuhi Peraturan Unified of Mixed Martial Arts . Pada 2020, UFC telah mengadakan lebih dari 500 acara . (sumber: https://www.ufc.com/history-ufc diakses pada tanggal 11 april 2020 pukul 12:54) 5 Peserta diperkenakan menggunakan seragam sesuai dengan disiplin bela diri yang didalaminya, bahkan juga diperbolehkan untuk menggunakan satu sarung tinju saja. Pertandingan akan diberhentikan apabila seorang lawan menyerah atau anggota petarung mengibarkan handuk untuk menghentikan pertarungan. -

B Wjfc; Ation .Score Lxx>K Today, a *L9-41 In

(PIIOSE 8800) Monday. 22, PAGE 20 SPORTS DETROIT EV E NINO TIME S CHERRY SPORTS December 1941 Hudson Team Heads 3-Man Event Pointe Swordsmen Win Greater Detroit Inter-Church Basket Ball The Grosso Pointe Sword Club Department 750 of Hudson Mo- 260 and a total of 1628. King’s ran add the Michigan plaque fenc- Praised n Shaul and ing tors today in an- was next with 210 tournament to trophy leads the third Theater DIVISION its list Has No Recess nua three-man championship 1725. The team is Joe Skonieczny, MEN'S today, but the Pointe team had 1 Nardtn Pk. Mrth. 39 Whitfield Mrth 3* tournament conducted at Chene- Ziggy Pluczyski, Bruno Konieczny. Baptlat «;i <;racr 31 strong opposition from the Salle Because the schedule must bo N'wratrrn Mrth TromhJy Recreation, with pins Sobczak. fifth with 158 and 1649, Stmtmoor Bapt. 41 Naxarvnr 28 de Tuscan Club, winning by only Pin completed before the city bowling Soovol Blue* 30 Dexter Baptlit 20 one point. Bill Osis, For over’average counting instead of has Anthony Baptlat Eugene Jaku- Times Rama. John Kowal- Scene! White* 43 *ld Klver 2d tournament begins in April. actual pinfall in determining the ski and Robert Konieczni. H P Preeby. 4d Trinity Oray* Id bowski and Dave Merriman com* W'd’d Ave. Pree. 23 Metro. Meth. 33 the winning team. Greater Detroit League will have Winners. Trinity Eagle* IS Church of Chrlat 29 posed Ten H P Baptlet IP Calvary Evan 25 teams competed. no suspension during the holiday Ken Bernheiner, Don Greko- Squash Title First Baptlet 11 St. -

164Th Infantry News: September 1998

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons 164th Infantry Regiment Publications 9-1998 164th Infantry News: September 1998 164th Infantry Association Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation 164th Infantry Association, "164th Infantry News: September 1998" (1998). 164th Infantry Regiment Publications. 55. https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 164th Infantry Regiment Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE 164TH INFANTRY NEWS Vot 38 · N o, 6 Sepitemlber 1, 1998 Guadalcanal (Excerpts taken from the book Orchids In The Mud: Edited by Robert C. Muehrcke) Orch id s In The Mud, the record of the 132nd Infan try Regiment, edited by Robert C. Mueherke. GUADALCANAL AND T H E SOLOMON ISLANDS The Solomon Archipelago named after the King of Kings, lie in the Pacific Ocean between longitude 154 and 163 east, and between latitude 5 and 12 south. It is due east of Papua, New Guinea, northeast of Australia and northwest of the tri angle formed by Fiji, New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides. The Solomon Islands are a parallel chain of coral capped isles extending for 600 miles. Each row of islands is separated from the other by a wide, long passage named in World War II "The Slot." Geologically these islands are described as old coral deposits lying on an underwater mountain range, whi ch was th rust above the surface by long past volcanic actions. -

Name: Jack Sharkey Career Record: Click Alias: Boston Gob Birth Name

Name: Jack Sharkey Career Record: click Alias: Boston Gob Birth Name: Joseph Paul Zukauskas Nationality: US American Birthplace: Binghamton, NY Hometown: Boston, MA Born: 1902-10-06 Died: 1994-08-17 Age at Death: 91 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Reach: 72 inches Division: Heavyweight Trainer: Tony Polazzolo Manager: Johnny Buckley Annotated Fight Record Photo (with megaphone) Biography Overview A fast and well-schooled fighter with no lack of heart and determination, Jack Sharkey is nonetheless overshadowed by the other heavyweight champions of his era. Sharkey’s indefatigable willingness to fight any opponent is best illustrated by his distinction in being the only man to have faced both Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis in prizefights. Though he consistently fought the best, Jack did not always win when up against the true upper crust of the division. In fact, his finest performances are perhaps his losses to Dempsey and Max Schmeling. Outspoken about his own confidence in his abilities and often surly or uncooperative in business, Jack had the talent to back up his ego. He remained a constant presence at or near the top of the heavyweight division for nearly a decade and solidified in his place in boxing lore by becoming heavyweight champion. Early Years Born Joseph Paul Zukauskas, the son of Lithuanian immigrants, Sharkey was born in Binghamton, New York but moved to Boston, Massachusetts as a young man. Sources report little of his early life until, at the outset of the First World War, teenaged Joseph repeatedly tried to enlist in the Navy. Turned down because of his age, he was not able to enlist until after the end of the war. -

'Aper Hawaii Needs” Toll of Innocent Bystander

—___ ___ __ UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII Sec. 562, P. LIBRARY Single Issue u. s. POS HONOLULU, T. H. U PA._ . 10c Honolulu, T. H. I 'aper Hawaii Needs ” $5.00 per year Permit No. 1 89 I by subscription VOL. I, NO. 4 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY AUG. 26, 1948 IZUKA ADMITS LYING; Witch Hunt Takes Toll PAMPHLET WAS GHOSTED Ichiro Izuka faced the cross-examination of Attorney Richard Gladstein in the Reinecke hearing, now in its third week at Honolulu’s Federal building, for the second successive day (Tuesday). of Innocent Bystander It was not until Izuka had left the Communist Party that he came to the conclusion the party advocated force and violence, the self-styled ex-Communist stated. A Book Salesman Loses Job He said he had been a Communist Party member for eight years. For Attending Public Hearing This statement made by the prosecution’s star witness Monday An encyclopaedia salesman was discharged from his job morning was only one of several because he had attended several sessions of the public hearing surprising revelations made during the course of his testimony. Under conducted by the Department of Public Instruction which is intensive probing by Mr. Gladstein, pursuing dismissal proceedings against Dr. and Mrs. John concerning— the widely—distributed- _ Reinecke_______ :.............. .... .. .............. - __ pamphlet, “The Truth About Com The Reineckes were suspended from their teaching posi- munism in Hawaii,” Mr. Izuka ad tions on charges of lacking the mitted, “I did not write it.” ideals of democracy because they reproached by this same manager Secret Pact are alleged Communists. -

Borah Denounces G. 0. P. Dry Plank

yO L. F4» NO. 224. (CUMrtflflrt Advtrtlaiiig od F»fB 10.X sourk ifewGHB j u ^ e 2 1 , 19 3 2 . (TWELVE PAGES) PEfidB TEEEB C!ENTS • - ’ ' v ’ BORAH DENOUNCES New York Hails Amelia IF U.S. TRIED G. 0. P. DRY PLANK M INVASION Sontor, Abo, h Answer To FEDERAL EMPLOYES Sort of Monroe Doctrine Democradc'S^ker of tte Qoestioii, Soys He W31 Not Enunciated By Former Ltbnzzi Is Sentenced ARE GIVEN WARNING Honse Gives Ont Fomial Support HooTor On P ht- Japanese Enyoy To Amer Statement To P r e » form R ecent Adopted. Most Take No Active Part In ica At Dinner For Grew. Bridgeport, Jirae 21.—(AP) —<<^another man, that he had been lur MakiDg Clear Ifis Views / WMhIngton. June 21.—(AP) — Politics Or They Will Lose Pleading guilty to murder in the ed by the murdered woman and that T okyo, June 21— (A P )— ^Viscount second degree, (zuy^ Edmund U briz- no jury would find him gidlty of There a furore of political Od Various Natkmal Prolh Kikujiro Ishil, former 'ambassador zi, 34 year old, bald-headed, be premediated mur^eri the first degree queetioninfl^ today in the wake of Their Jobs. spectacled fruit store clerk of Nor murder charge which woul . have to the United States, enunciated, a 4 Senator Borah's dramatic announce- walk, was sentenced to life imprison made ths death penalty mandatory sort of Monroe Doctrine for Asia to- Ions — Observers .See meat that President Hoover will ment at Wethersfield by Judge was withdrawn.' Washington, June 21 — (AP) — night at a dinner for Joseph C. -

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

Senate Resolution No. 1653 Senator TEDISCO BY: Billy Petrolle Posthumously Upon the HONORING Occasion of Being Inducted I

Senate Resolution No. 1653 BY: Senator TEDISCO HONORING Billy Petrolle posthumously upon the occasion of being inducted into the Schenectady School District Athletic Hall of Fame WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to pay tribute to outstanding athletes who have distinguished themselves through their exceptional performance, attaining unprecedented success and the highest level of personal achievement; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern and in full accord with its long-standing traditions, this Legislative Body is justly proud to honor Billy Petrolle posthumously upon the occasion of being inducted into the Schenectady School District Athletic Hall of Fame on Monday, September 16, 2019, at Glen Sanders Mansion, Scotia, New York; and WHEREAS, Billy Petrolle was raised in Schenectady, New York, where he attended public school and started boxing as an amateur at just 15 years old; and WHEREAS, Known as Fargo Express, Billy Petrolle began his illustrious pro boxing career in 1922; once rated as the top challenger for the welterweight, junior-welterweight and lightweight titles, he fought for the World Lightweight Title on November 4, 1932, at Madison Square Garden; and WHEREAS, With other notable fights against Barney Ross and Kid Berg, Billy Petrolle knocked out Battling Battalino in front of 18,000 fans at Madison Square Garden on March 24, 1932, and defeated Jimmy McLarnin at MSG on November 21, 1930; and WHEREAS, Participating in ten current or past World Championships, Billy Petrolle won five of them; in addition to -

Up Against the Ropes: Peter Jackson As ''Uncle Tom" in America

Up against the Ropes Peter Jackson As “Uncle Tom” in America Susan F. Clark When Peter Jackson, Australia’s heavyweight champion, arrived in America in 1888, he was known as “The Black Prince”; by the time he left for home, 12 years later, he was more often thought of as “Uncle Tom.” How this per- fect fighting machine came to be identified with America’s well-known sym- bol of acquiescence is a story that illuminates the cultural, social, and racial environment of late 19th-century America. It is a narrative that features the highly commercial, image-conscious worlds of boxing and theatre against a background of extreme racial prejudice. Most importantly, it is a cautionary tale that reflects the dangerous and mutable ability of popular entertainments to endow damaging stereotypes with a semblance of truth. Peter Jackson came to the United States looking for a fight. He was a de- termined, disciplined, and talented boxer who was optimistic that he could defeat America’s finest boxers. The battle that Jackson fought in America was one he was ill-equipped to fight, for it had little to do with his technical skill or physical prowess. It was a struggle against America’s long-standing racial schism, which divided Americans by the color of their skin. When Jackson, a novice to American culture, allowed his manager to convince him to be “whipped to death” nightly before packed houses as Uncle Tom in a touring production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, his battle in America was all but over. Never again would he be taken seriously as a heavyweight contender. -

Boxing Men: Ideas of Race, Masculinity, and Nationalism

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Boxing Men: Ideas Of Race, Masculinity, And Nationalism Robert Bryan Hawks University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hawks, Robert Bryan, "Boxing Men: Ideas Of Race, Masculinity, And Nationalism" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1162. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1162 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOXING MEN: IDEAS OF RACE, MASCULINITY, AND NATIONALISM A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of Mississippi's Center for the Study of Southern Culture by R. BRYAN HAWKS May 2016 Copyright © 2016 by R. Bryan Hawks ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Jack Johnson and Joe Louis were African American boxers who held the title of World Heavyweight Champion in their respective periods. Johnson and Louis constructed ideologies of African American manhood that challenged white hegemonic notions of masculinity and nationalism from the first decade of the twentieth century, when Johnson held the title, through Joe Louis's reign that began in the 1930's. This thesis investigates the history of white supremacy from the turn of the twentieth century when Johnson fought and does so through several lenses. The lenses I suggest include evolving notions of masculinity, Theodore Roosevelt's racially deterministic agendas, and plantation fiction. -

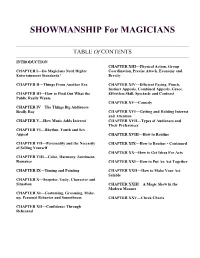

SHOWMANSHIP for MAGICIANS

SHOWMANSHIP For MAGICIANS TABLE Of CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER XIII—Physical Action, Group CHAPTER I—Do Magicians Need Higher Coordination, Precise Attack, Economy and Entertainment Standards? Brevity CHAPTER II—Things From Another Era CHAPTER XIV—Efficient Pacing, Punch, Instinct Appeals, Combined Appeals, Grace, CHAPTER III—How to Find Out What the Effortless Skill, Spectacle and Contrast Public Really Wants CHAPTER XV—Comedy CHAPTER IV—The Things Big Audiences Really Buy CHAPTER XVI—Getting and Holding Interest and Attention CHAPTER V—How Music Adds Interest CHAPTER XVII—Types of Audiences and Their Preferences CHAPTER VI—Rhythm, Youth and Sex Appeal CHAPTER XVIII—How to Routine CHAPTER VII—Personality and the Necessity CHAPTER XIX—How to Routine - Continued of Selling Yourself CHAPTER XX—How to Get Ideas For Acts CHAPTER VIII—Color, Harmony, Sentiment, Romance CHAPTER XXI—How to Put An Act Together CHAPTER IX—Timing and Pointing CHAPTER XXII—How to Make Your Act Salable CHAPTER X—Surprise, Unity, Character and Situation CHAPTER XXIII—A Magic Show in the Modern Manner CHAPTER XI—Costuming, Grooming, Make- up, Personal Behavior and Smoothness CHAPTER XXV—Check Charts CHAPTER XII—Confidence Through Rehearsal INTRODUCTION The fact that I feel there to be a definite need for this book is evidenced by my having written it. While this work is intended primarily for magicians, there is very much here, particularly the analysis of audience preferences and appeals, which applies to entertainers generally. There is a right way and a wrong way of doing anything. But the right way of yesterday is not necessarily the right way of today. -

Childrens Syllabus White

Childrens Syllabus White - Pro Blue Revised - March 2019 White (Gloves Recommended) Probation Orange (Nunchakus Required) Progress Check 1 Progress Check 1 Jab Inner Crescent Kick Cross Back Fist Front Kick Jab,Cross,Inner Crescent Kick(Rear)(Adv),Back Fist(Lead) Progress Check 2 Progress Check 2 Roundhouse Kick Back Kick Toes point down to the ground and look at target High Outer Block From horse stance Axe Kick Lower Outer Block From horse stance Jab,Cross,Front Kick(Rear)(St),Back Kick(Lead) Middle Outer Block From horse stance Nunchakus Demonstrate basic control, spinning and strikes Progress Check 3 Progress Check 3 Jab,Cross,Front Kick Combo 3 Jab, Hook(Lead), Cross Jab,Cross,Roundhouse Lower Inner Block From horse stance Jab,Cross,Jab Level Notes - For grading instructors will be testing syllabus from progress check 1 to 3. Combos are Level Notes - Weapons begin as of this level starting with padded Nunchaku. Students must NOT assessed on fluency and sharpness of technique. Students are also assessed on their behaviour and leave weapons laying around and must ask for permission before using them. effort through out the warm up and stretch. Probation Yellow (Gloves Required) Orange (Nunchakus Required) Progress Check 1 Progress Check 1 Hook Punch Body Jab Stationary lead straight punch to body Push Kick Twisting Kick Stand With Guard Stand from the ground without using hands Jab, Cross, Twisting Kick(Rear)(Adv), Body Rip(Rear) Jab,Cross,Hook(Lead),Push Kick(Rear) Progress Check 2 Progress Check 2 Side Thrust Kick Look at target and