Lives Between Lives Between March 8—May 6, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DANI GAL *1975 Jerusalem, IL Lives in Berlin, DE

DANI GAL *1975 Jerusalem, IL Lives in Berlin, DE Education Depuis 1788 2005 Cooper Union for the Advancment of Science and Art, New York City, USA Freymond-Guth Fine Arts 2000 - 2005 Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste Städelschule, Frankfurt/ Riehenstrasse 90 B Main, DE (Prof. Ayse Erkmen) CH 4058 Basel 1998 - 2000 Bezalel Academy for Art and Design, Jerusalem, IL T +41 (0)61 501 9020 1997 - 1998 Avni Institute, Tel Aviv, IL offi[email protected] www.freymondguth.com Soloshows (selection) 2015 Sono vietate le discussioni politiche, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zürich, CH 2014 The Jewish Museum, New York, USA, cur. Jens Hoffmann Tel Aviv Museum of Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, IL, cur. Ellen Ginton Kunstraum Innsbruck, Innnsbruck, AT, cur. Karin Pernegger Zochrot, Tel Aviv, IL 2013 Kunsthalle St. Gallen, cur. Giovanni Carmine, CH Nacht und Nebel, Turku Art Museum, FIN Failed to Bind, Galerie Kadel Wilborn, Düsseldorf, DE 2012 Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental., Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Dumitrescu‘s Dream - Le Grand Relay, Lap #1, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH 2011 Kunstverein Arnsberg, Arnsberg, DE Fruits, Flowers & Clouds, solo presentation, MAK, Vienna, AT 2010 Chanting Down Babylon, w139 Arts Centre, Amsterdam, NL Dumitrescu‘s Dream, Lüttgenmeijer, Berlin, DE 2009 The Shooting of Officers, Freymond-Guth & Co. Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Chanting Down Babylon, Halle für Kunst, Lüneburg, DE Project Room, Pecci Museum Prato, IT 2007 La Battaglia, Freymond-Guth & Co. Fine Arts, Zurich, CH 2004 Holdup, Or Gallery, Vancouver B.C., CA Groupshows (selection) 2015 Das ist Österreich!, Voralberg Museum, Bregenz, AT Europa. -

To the Press Dani

To the press Dani Gal «Do you suppose he didn't know what he was doing, or knew what he was doing and didn't want anyone to know?» 9 November 2013 – 19 January 2014 Press preview: Friday, 8 November 2013, from 11 a.m. on Opening: Friday, 8 November 2013, 6 p.m. The starting point of the films and sound installations by Dani Gal (*1975, Jerusalem, IL) are mostly existing historical documentaries which the artist examines and subtly manipulates or artistically reconstructs on the basis of his research. In addition to conventional text and image analysis he uses language and sound to exemplify his central themes of history, the writing of history and the associated mechanisms of selection and exclusion which define how certain events are perceived. He is concerned with putting formed opinions on historical events into perspective or giving them new impulses. In his exhibition Dani Gal presents the short film Wie aus der Ferne (As from Afar), co-produced by Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, which is based on a text by Ludwig Wittgenstein about memory images. To what extent are images of a memory different from images that come with expectation from images of a daydream? With this question as a central theme he examines the friendship between Simon Wiesenthal and Albert Speer. The former was a Holocaust survivor who dedicated his life to the search for Nazi criminals, the latter was Hitler’s architect and confidant who showed regret after being sentenced to 20 years imprisonment and was prepared to take responsibility for Nazi crimes. -

Artist Talk Mit Phyllida Barlow Und Lecture Performance Von Dani Gal

DIE KÜNSTLER PHYLLIDA BARLOW UND DANI GAL SPRECHEN IN DER SCHIRN ÜBER IHRE WERKE IN DER AUSSTELLUNG „POWER TO THE PEOPLE“ ARTIST TALK MIT PHYLLIDA BARLOW UND LECTURE PERFORMANCE VON DANI GAL DIENSTAG, 15. MAI 2018 / SAMSTAG, 26. MAI 2018, AB 19 UHR SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT GEBÜHR 9 €, ERMÄSSIGT 7 €, ABENDKASSE, KEIN VORVERKAUF ANMELDUNG: 069.299882-112, [email protected] IN ENGLISCHER SPRACHE Noch bis zum 27. Mai 2018 präsentiert die Schirn mit „Power to the People. Poltische Kunst jetzt“ eine große Ausstellung zur politischen Kunst der Gegenwart. Im Mai sprechen zwei der an der Ausstellung beteiligten Künstler noch einmal in der Schirn über ihr Werk: am 15. Mai 2018, um 19 Uhr findet ein Künstlergespräch mit Phyllida Barlow statt und am 26. Mai 2018, um 19 Uhr hält Dani Gal im Rahmen des SATUDAY BEFORE CLOSING einen performativen Vortrag. Beim Artist Talk mit Phyllida Barlow spricht die Kuratorin Martina Weinhart am 15. Mai 2018, um 19 Uhr mit der britischen Künstlerin über ihr skulpturales Schaffen sowie über ihre Installation Untitled: 100banners2015 (2015), die in der Schirn-Rotunde zu sehen ist. Mit dieser raumgreifenden Installation bezieht sich Barlow auf Fahnen als Symbole von Zusammengehörigkeit und Macht – und für Widerstand gegen Letztere. Typischerweise versinnbildlichen Fahnen Länder, aber sie werden auch bei Paraden oder Protestveranstaltungen genutzt. Barlow entzieht den Fahnen bewusst ihre Bedeutung, denn es ist weder Schrift noch eine Botschaft zu erkennen. Die Banner sind schmucklos und beinahe laienhaft zusammengenäht. Die fragile Befestigung durch Sandsäcke verstärkt zudem den Eindruck des Improvisierten. Mit ihrer Strategie des künstlerischen Dilettantismus gelingt es Barlow, den Träger politischer Bedeutung schlechthin zu entmystifizieren. -

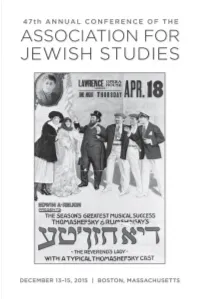

Jewish Studies Program

Association for Jewish Studies c/o Center for Jewish History 15 West 16th Street New York, NY 10011-6301 Phone: (917) 606-8249 Fax: (917) 606-8222 E-mail: [email protected] www.ajsnet.org President AJS Staff Jonathan D. Sarna Rona Sheramy Brandeis University Executive Director Vice President / Membership Ilana Abramovitch and Outreach Conference Program Associate Carol Bakhos Laura Greene UCLA Conference Manager Vice President / Program Karin Kugel Pamela S. Nadell Program Book Designer; Website Manager; American University Managing Editor, AJS Perspectives Vice President / Publications Shira Moskovitz Leslie Morris Program and Membership Coordinator; University of Minnesota Manager, Distinguished Lectureship Program Secretary / Treasurer Amy Weiss Zachary Baker Grants and Communications Coordinator Stanford University Cover Designer Ellen Nygaard The Association for Jewish Studies is a constituent society of the American Council of Learned Societies. The Association for Jewish Studies wishes to thank the Center for Jewish History and its constituent organizations—the American Jewish Historical Society, the American Sephardi Federation, the Leo Baeck Institute, Yeshiva University Museum, and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research—for providing AJS with office space at the Center for Jewish History. Cover credit: The Yiddish theater poster for “The Reverend’s Lady” at the Opera House in Lawrence, Massachusetts, April 18, 1918; Theater and Film Poster Collection of Abram Kanof; P-978; drawer 2C/folder number 30; item number 1967.001.044; American Jewish Historical Society, Boston, MA and New York, NY. Copyright © 2015 No portion of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the express written permission of the Association for Jewish Studies. -

An Die Presse Dani

An die Presse Dani Gal «Do you suppose he didn't know what he was doing, or knew what he was doing and didn't want anyone to know?» 9. November 2013 – 19. Januar 2014 Pressetermin mit Vorbesichtigung: Freitag, 8. November 2013, 11 Uhr Eröffnung: Freitag, 8. November 2013, 18 Uhr Ausgangspunkt der Film- und Toninstallationen von Dani Gal (*1975, Jerusalem, IL) sind meist bereits vorhandene historische Dokumentationen, die der Künstler untersucht und subtil manipuliert oder auf Basis seiner Recherchen künstlerisch rekonstruiert. Neben der konventionellen Text- und Bildanalyse verwendet er Sprache und Ton zur Veranschaulichung seiner zentralen Themen Geschichte, Geschichtsschreibung und damit verbundenen Auswahl- und Ausschlussmechanismen, welche die Sichtweisen über gewisse Ereignisse definieren. Ihm ist es ein Anliegen, gemachte Meinungen zu historischen Geschehnissen zu relativieren oder neue Impulse zu geben. In seiner Einzelausstellung präsentiert Dani Gal den von der Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen koproduzierten Kurzfilm Wie aus der Ferne (As from Afar), der von einem Text von Ludwig Wittgenstein über Gedächtnisbilder ausgeht. Inwiefern unterscheiden sich Bilder einer Erinnerung von Bildern, die von einer Erwartung geweckt werden, von Bildern eines Tagtraums? Mit dieser Frage als Leitgedanke thematisiert er die Freundschaft zwischen Simon Wiesenthal und Albert Speer. Ersterer ist ein Überlebender des Holocaust, der sein Leben der Suche nach Naziverbrechern widmete; letzterer war Hitlers Architekt und Vertrauter, der nach seiner Verurteilung zu 20 Jahren Haft Reue zeigte und Verantwortung für die Verbrechen der Nationalsozialisten zu übernehmen bereit war. Gals dokumentarischer Ansatz und seine poetische Narration beleuchten die Leerstelle zwischen Realität und Darstellung, zwischen Erinnerung und Erfindung, indem sie die Geschichte als offenen Prozess der subjektiven Interpretation entlarven. -

İsimsiz (12. İstanbul Bienali), 2011 Untitled (12Th Istanbul Biennial), 2011 Katalog the Catalogue

İsimsiz (12. İstanbul Bienali), 2011 Untitled (12th Istanbul Biennial), 2011 Katalog The Catalogue 12. İstanbul Bienali Kataloğu İstanbul Kültür Sanat Vakfı ve Yapı Kredi Yayınları tarafından, Vehbi Koç Vakfı’nın katkılarıyla yayımlanmıştır. The Catalogue to the 12th Istanbul Biennial is copublished by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts and Yapı Kredi Publications with the invaluable contribution of Vehbi Koç Foundation. Katalog | The Catalogue Biennial Sponsor Bienal Sponsoru The Catalogue | Katalog İçindekiler / Contents 12 Önsöz Foreword — Bige Örer 14 Giriş Introduction — Jens Hoffmann & Adriano Pedrosa 19 Makaleler Essays 20 Bienal Politikaları Politics of Biennials — Jessica Morgan 36 Kırmızıya Kayma: İki Cepheli Bir Mücadele Shifting to Red: A Struggle on Two Fronts — Julieta González Katalog 50 Dördüncü Eleştiri The Fourth Critique | — João Ribas 62 Soyutlama, Tarihe Meydan Okuyor Abstraction Defies History — Chus Martinez The Catalogue 68 Bu Mekân Artık Bu Yer Değil This Space Is No Longer This Place — Aykut Köksal 81 Söyleşi Conversation 103 Sergi The Exhibition 107 İsimsiz (Soyutlama) Untitled (Abstraction) 161 “İsimsiz” (Ross) “Untitled” (Ross) 197 “İsimsiz” (Pasaport) “Untitled” (Passport) 241 İsimsiz (Tarih) Untitled (History) 289 “İsimsiz” (Ateşli Silahla Ölüm) “Untitled” (Death by Gun) Sanatçılar 146 Zarouhie Abdalian 169 Colter Jacobsen 354 İstanbul’u Hatırlamak Artists 316–7 Bisan Abu-Eisheh 252–3 Voluspa Jarpa Remembering Istanbul 318–9 Eylem Aladoğan 133 Magdalena Jitrik 296–7 Eddie Adams 327 William E. Jones 356 İsimsiz (Film) 177, 274 Jonathas de Andrade 283–4 Tamás Kaszás & Anikó Loránt Untitled (Film) 207 Claudia Andujar 251 Ali Kazma 147–8 Nazgol Ansarinia 138 Annette Kelm 360 İstanbul Kültür Sanat Vakfı 307, 320 Edgardo Aragón 119 Edward Krasinski Istanbul Foundation for 184 Ardmore Ceramic Art Studio 124 Faouzi Laatiris Culture and Arts 275 Marwa Arsanios 123 Runo Lagomarsino 276 Yıldız Moran Arun 232 Tim Lee 361 12. -

Informationen Zu Den Workshops Und Anregungen Für Einen Individuellen Ausstellungsbesuch Mit Schulklassen

Informationen zu den Workshops und Anregungen für einen individuellen Ausstellungsbesuch mit Schulklassen Dani Gal «Do you suppose he didn't know what he was doing, or knew what he was doing and didn't want anyone to know?» (9. November 2013 – 19. Januar 2014) Inhalt Einführung 1 Workshops in der Ausstellung Informationen zur Ausstellung, Inhalt der Workshops, Zeitraum, Zielgruppen, Zeitaufwand, Ablauf 2 Individueller Besuch mit Schulklassen Zeitaufwand in der Kunst Halle und Nachbearbeitung in der Schule 4 Ausstellungsrundgang Informationen und Impulse 5 Anhang: Anmeldeformular zu den Workshops Impressum Vermittlungskonzept: Cynthia Gavranic, Kunstvermittlerin Texte zur Ausstellung: Giovanni Carmine, Direktor und Maren Brauner, Assis- tenzkuratorin Photos: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gunnar Meier Vorderseite: Dani Gal, Wie aus der Ferne (As from Afar), 2013 (Filmstill) Einführung "Das kann ich auch!" und "Wieso soll das hier Kunst sein?" sind zwei der häufig gehörten Bemerkungen im Kontext von zeitgenössischer Kunst. Dabei kann diese zahlreiche Kompetenzen der SchülerInnen stärken. Studien haben ergeben, dass der Umgang mit zeitgenössischer Kunst und Künstlern das ge- samte Lernverhalten fördert, dass die Dialogbereitschaft und das Respektie- ren von anderen Positionen entwickelt werden und dass Verantwortungsbereit- schaft sowie Empathie wachsen können. Zeitgenössische Kunst kann nicht mit Kriterien wie "das ist schön", "der kann gut malen" oder "das hänge ich mir ins Wohnzimmer" bewertet werden. Sie erfordert eine Bereitschaft, sich auf sie einzulassen und sie erst einmal genau zu betrachten. Dabei geht es in erster Linie nicht um das "Verstehen" der Kunstwerke, sondern vielmehr um die individuellen Denkprozesse, welche sie anregen. Ziel der vorliegenden Sammlung von Impulsen für den Ausstellungsbesuch und die gestalterische und Themen vertiefende Nachbearbeitung in der Schule ist, die SchülerInnen erlebnisreich mit den Gedankenwelten und Arbeitspro- zessen junger zeitgenössischer KünstlerInnen vertraut zu machen. -

Deliverable D2.4 As

Ref. Ares(2021)220364 - 11/01/2021 Deliverable D2.4 Database of Films, Artworks, and other Visual Culture Products Lead-beneficiary OFM Work Package No. and Title WP2 Curation and advanced digitization of assets Work Package Leader OFM Relevant Task Task 2.8 Curation and advanced digitization of popular culture content Task Leader HUJI Main Author(s) HUJI (Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Lital Henig, Noga Stiassny) Contributor(s) DFF (Kerstin Herlt, David Kleingers, Bianca Sedmak) HUJI (Talia Litvinov, Shir Ventura, Julia Marie Wittorf) LBI/HUJI (Fabian Schmidt) LBI (Ingo Zechner) Reviewer(s) LBI (Ingo Zechner, Sema Colpan) OFM (Anna Högner, Michael Loebenstein) Dissemination Level Public Due Date M24 (2020-12) Version (No., Date) V1.9, 2021-01-11 This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 822670. www.vhh-project.eu Database of Films, Artworks and other Visual Culture Content Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 3 2. THE VHH POPULAR CULTURE COLLECTION ................................................................ 4 2.1. Migrating images ........................................................................................................ 5 2.2. Representations of the Holocaust in popular culture ............................................... 7 2.3. VHH Premium Content ........................................................................................... -

DANI GAL *1975 Jerusalem, IL Lives in Berlin, DE

DANI GAL *1975 Jerusalem, IL Lives in Berlin, DE Education Depuis 1788 2005 Cooper Union for the Advancment of Science and Art, New York City, USA Freymond-Guth Fine Arts 2000 - 2005 Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste Städelschule, Frankfurt/ Riehenstrasse 90 B Main, DE (Prof. Ayse Erkmen) CH 4058 Basel 1998 - 2000 Bezalel Academy for Art and Design, Jerusalem, IL T +41 (0)61 501 9020 1997 - 1998 Avni Institute, Tel Aviv, IL offi[email protected] www.freymondguth.com Soloshows (selection) 2017 Hegemon, Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf, DE 2015 Videoart at Midnight, Babylon, Berlin, DE Sono vietate le discussioni politiche, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zürich, CH 2014 The Jewish Museum, New York, USA, cur. Jens Hoffmann Tel Aviv Museum of Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, IL, cur. Ellen Ginton Kunstraum Innsbruck, Innnsbruck, AT, cur. Karin Pernegger Zochrot, Tel Aviv, IL 2013 Kunsthalle St. Gallen, cur. Giovanni Carmine, CH Nacht und Nebel, Turku Art Museum, FIN Failed to Bind, Galerie Kadel Wilborn, Düsseldorf, DE 2012 Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental., Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Dumitrescu‘s Dream - Le Grand Relay, Lap #1, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH 2011 Kunstverein Arnsberg, Arnsberg, DE Fruits, Flowers & Clouds, solo presentation, MAK, Vienna, AT 2010 Chanting Down Babylon, w139 Arts Centre, Amsterdam, NL Dumitrescu‘s Dream, Lüttgenmeijer, Berlin, DE 2009 The Shooting of Officers, Freymond-Guth & Co. Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Chanting Down Babylon, Halle für Kunst, Lüneburg, DE Project Room, Pecci Museum Prato, IT 2007 La Battaglia, Freymond-Guth & Co. Fine Arts, Zurich, CH 2004 Holdup, Or Gallery, Vancouver B.C., USA Groupshows (selection) 2017 Lives Between, Kadist, San Francisco, USA Kult! Legenden, Stars und Bildikonen, Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen, Friedrichshafen, DE 2016 Heart of Noise, Innsbruck, AT Collection on Display: Momentary Monuments, Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich, CH Private Offices, Nancy Rosen, NY, USA 2015 Das ist Österreich!, Voralberg Museum, Bregenz, AT Europa. -

The Time That Remains 2018.10.27 - 2018.11.24

THE TIME 剩余的时间 | 房间 6 号 THAT REMAINS Room No.6 剩余的时间 | 房间 6 号 The Time That Remains 2018.10.27 - 2018.11.24 Grey Cube of Goethe - Institut China, 798 Art District, Bejing 歌德学院灰盒子空间,北京 798 艺术区 Artists | Dani Gal | Judith Hopf | Bjørn Melhus | Hila Peleg Julian Rosefeldt | Clemens von Wedemeyer Deng Dekuan | Hu Tao | Jiang Li | Tang Chao | Wang Haiqing | Payne Zhu Curator | Ma Wen 艺术家 | 丹尼·戈尔 | 朱迪斯·霍普夫 | 比约恩·梅尔胡斯 | 希拉·法勒 朱利安·罗斯菲德 | 克莱门斯·冯·魏德迈 邓德宽 | 胡滔 | 蒋力 | 唐潮 | 王海清 | 佩恩恩 策展人 | 马文 导言 展览 " 剩余的时间 | 房间 6 号 ",从阿甘本的著作《剩余的时间 - 解读罗马书》借用了标题,他通 过对罗马书的第一句话 10 个词的分析,阐释了时间是三维的,而不是线性的,让人马上联想到时 间的空间性。 同样从罗马书中获得了启示的马丁路德,通过对圣经的翻译,促成了现代德语的形成。一般认为 歌德学院只是一个德语学习的机构,而在中国它的含义有着明显的不同,从 1988 到 2004 年它 是唯一允许存在的外来文化机构。可以说在过去的 30 年里,它成为了很多人试图了解多元文化, 追求精神自由的庇护所。很明显艺术与自身的辩论,艺术与现实的对抗,总是伴随着失败,分歧, 风险 ..... 歌德灰盒子的空间语境在于,它位处曾是 1951 年由东德参与设计的军事工业厂区,建筑物具有典 型的包豪斯风格,空间改造设计是由 Albert Speer + Partner 完成,这也是一个悖论的混合体。 时间和空间的虚构是影像作品的重要的材料,影像可以把过去变为一种 " 拯救性记忆 ",它通过捕 捉每一个瞬间,刺破了线性时间,把过去重新召唤到当下,使之充满救赎的可能性。剩余的时间 意味着救赎的不在场,它无法被拯救,可是又随时会到来。每一个当下都是潜在事件的发生点, 发生随时会到来,时间随时会终结。过去并不是进步主义叙事中的一个低级阶段,它从来都是和 当下相关。 这个展览不想成为遵循某一论点的展览,而是去发散,去追问在未来或者说在剩余的时间中,在 异质空间的不断生产中,不同语境下的文化交流,在残酷的现实中,在废墟里和荒漠中,还有什 么可能性? 而残留者,就是和时间构成脱节,倒错关系的人,就是展览作品的作者,片中的人物,及观者。 他们通过与时代的疏离,去捕捉一个还没有过的当下,去追问到底什么残留了下来。 灰盒子展览空间如同一个小型电影院,12 部影像作品分别被投射出来,这个空间被随时替换成不 同的 12 个场景,它切开了一个通往另一个世界的窗口,通往作品中的起居室,监狱,浴室,厨房 , " 伪 " 房间 ..... 展览由三部分组成,共同展现对“时间的结构,空间的身份,事件的显现,行动的策略,还没有 过的当下”等问题的思考。 第一部分选择了 6 个工作生活在德国的艺术家 , 包括 Dani Gal | Judith Hopf | Bj rn Melhus | Hila Peleg | Julian Rosefeldt | Clemens von Wedemeyer。他们的作品从不同的时间线,不ø 同的空间身份,他们各自的故事与历史交织在一起, 形成了一个多解读性的网状结构。空间的身 份被切割成不同层面,瞬间的真实与虚构与空间和场所的复杂性被编织到一起。 第二部分,通过网络,招募了 6 个不超过 30 岁的中国艺术家邓德宽 | 胡滔 | 蒋力 | 唐潮 | 王海清 | 佩恩恩,他们的作品同样与房间相关,在过去的 30 年中,中国社会实体空间与虚拟空间的剧烈 变迁成为了每个人的生活非常重要的部分。艺术家们通过打开不同的时间线,在当下的生存方式 中刺入个体经验,以一种独特的方式悬置了规则。 第三部分,在 2018 年 10 月 27 号的开幕式之后,邀请两位学者吴冠军教授,姜宇辉教授与策展 人马文进行对谈,对剩余的时间及身体与空间关系等进行解读。2108 年 10 月 28 号邀请 6 个不 同身份的居民,即兴的讲述他们和房间的故事,上演“大脑电影 Cinema of Brain”。 马文 Introduction The title of the exhibition "The Time That Remains: Room No.6" borrowed from a book by Giorgio Agamben. -

Putting Rehearsals to the Test

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 19 Putting Rehearsals to the Test Practices of Rehearsal in Fine Arts, Film, Theater, Theory, and Politics Sabeth Buchmann Ilse Lafer Constanze Ruhm (Eds.) Putting Rehearsals to the Test Practices of Rehearsal in Fine Arts, Film, Theater, Theory, and Politics Putting Rehearsals to the Test Practices of Rehearsal in Fine Arts, Film, Theater, Theory, and Politics Sabeth Buchmann Ilse Lafer Constanze Ruhm (Eds.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) Volume 19 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present this new volume in the publication series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. The series, published in cooperation with our highly committed partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of con temporary thought about art practices and art theories. The volumes in the series comprise collected contributions on subjects that form the focus of dis course in terms of art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is pub lished in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Authors of high international repute are invited to write con tributions dealing with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities such as international conferences, lecture series, institutespecific research focuses, or research projects serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. With Putting Rehearsals to the Test: Practices of Rehearsal in Fine Arts, Film, Theater, Theory, and Politics we are launching volume nineteen of the series. -

Any Resemblance to Real Persons, Living Or Dead, Is Purely Coincidental

Jean-Claude Freymond-Guth Limmatstrasse 270 Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. 8005 Zürich, Switzerland DANI GAL T +41 (0)44 240 04 81 offi[email protected] www.freymondguth.com Wed - Fr 12 – 18hrs 1 September - 13 October 2012 Saturday 12 – 17hrs Or by appointment Opening 31 August 2012, 18hrs We are very pleased to open our new gallery space at Löwenbräu in Zurich with a solo show by Dani Gal (*1975, Jerusalem, lives in Berlin). Gal has received much attention and acclaim in the past years through his participation at the Venice Biennal and Istanbul Biennal in 2011 as well a.o. institutional shows at Frankfurter Kunstverein, New Museum NY, Zabludowicz Collection London, Kunsthalle Vienna and Wattis Institute San Francisco this year. He is currently nominated for the Nationalgalerie Award for Young Art in Berlin. By means of intensive research and examination of historical images, texts and sound docu- ments of past and/or current political and cultural occurrences, Gal interrogates how personal and collective history and memorization is produced, selected and passed on through time and space. For this exhibition Gal works with the excessive media coverage of one of the most iconic terror attacks which took place during the Munich Olympics in 1972 - September 5th marks the 40th anniversary of the attack. More than ten films, both fiction and documentary, have re- enacted this event. Using these films as a reference point, Gal creates the film installation Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental., that consists of two video pieces and one object.