Rio Grande Shiner Petition Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carmine Shiner (Notropis Percobromus) in Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Carmine Shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada THREATENED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports COSEWIC 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus and rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. v + 17 pp. Houston, J. 1994. COSEWIC status report on the rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-17 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair, COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. In 1994 and again in 2001, COSEWIC assessed minnows belonging to the rosyface shiner species complex, including those in Manitoba, as rosyface shiner (Notropis rubellus). For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la tête carminée (Notropis percobromus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Notropis Girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis Tetranema)

Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Species Status Assessment Report for the Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) Arkansas River shiner (bottom left) and peppered chub (top right - two fish) (Photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Version 1.0a October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Albuquerque, NM This document was prepared by Angela Anders, Jennifer Smith-Castro, Peter Burck (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – Southwest Regional Office) Robert Allen, Debra Bills, Omar Bocanegra, Sean Edwards, Valerie Morgan (USFWS –Arlington, Texas Field Office), Ken Collins, Patricia Echo-Hawk, Daniel Fenner, Jonathan Fisher, Laurence Levesque, Jonna Polk (USFWS – Oklahoma Field Office), Stephen Davenport (USFWS – New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Mark Horner, Susan Millsap (USFWS – New Mexico Field Office), Jonathan JaKa (USFWS – Headquarters), Jason Luginbill, and Vernon Tabor (Kansas Field Office). Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema), version 1.0, with appendices. October 2018. Albuquerque, NM. 172 pp. Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 INTRODUCTION (CHAPTER 1) The Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) are restricted primarily to the contiguous river segments of the South Canadian River basin spanning eastern New Mexico downstream to eastern Oklahoma (although the peppered chub is less widespread). Both species have experienced substantial declines in distribution and abundance due to habitat destruction and modification from stream dewatering or depletion from diversion of surface water and groundwater pumping, construction of impoundments, and water quality degradation. -

Edna Assay Development

Environmental DNA assays available for species detection via qPCR analysis at the U.S.D.A Forest Service National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation (NGC). Asterisks indicate the assay was designed at the NGC. This list was last updated in June 2021 and is subject to change. Please contact [email protected] with questions. Family Species Common name Ready for use? Mustelidae Martes americana, Martes caurina American and Pacific marten* Y Castoridae Castor canadensis American beaver Y Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus American bullfrog Y Cinclidae Cinclus mexicanus American dipper* N Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel Y Soricidae Sorex palustris American water shrew* N Salmonidae Oncorhynchus clarkii ssp Any cutthroat trout* N Petromyzontidae Lampetra spp. Any Lampetra* Y Salmonidae Salmonidae Any salmonid* Y Cottidae Cottidae Any sculpin* Y Salmonidae Thymallus arcticus Arctic grayling* Y Cyrenidae Corbicula fluminea Asian clam* N Salmonidae Salmo salar Atlantic Salmon Y Lymnaeidae Radix auricularia Big-eared radix* N Cyprinidae Mylopharyngodon piceus Black carp N Ictaluridae Ameiurus melas Black Bullhead* N Catostomidae Cycleptus elongatus Blue Sucker* N Cichlidae Oreochromis aureus Blue tilapia* N Catostomidae Catostomus discobolus Bluehead sucker* N Catostomidae Catostomus virescens Bluehead sucker* Y Felidae Lynx rufus Bobcat* Y Hylidae Pseudocris maculata Boreal chorus frog N Hydrocharitaceae Egeria densa Brazilian elodea N Salmonidae Salvelinus fontinalis Brook trout* Y Colubridae Boiga irregularis Brown tree snake* -

Rio Costilla Habitat Improvement Project

Decision Memo Rio Costilla Habitat Improvement Project USDA Forest Service, Southwestern Region Questa Ranger District, Carson National Forest Taos County, New Mexico (Sections 1, 2, 11, 12, 14, and 15 of Township 30 North, Range 15 East) Background An interdisciplinary analysis on this project was conducted and is documented in a project record. Source documents from the project record are incorporated by reference throughout this decision memo by showing the document number in brackets [PR #]. Please refer to Appendix A for the project record index. The Questa Ranger District of the Carson National Forest, in partnership with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, proposes to improve in- stream habitat conditions within the Rio Costilla [PR #77, 128]. The Valle Vidal Unit of the Carson National Forest attracts hundreds of anglers annually. The Rio Costilla is the largest stream in the Valle Vidal and a favorite among anglers. Anglers travel to this area in large part to pursue the native Rio Grande cutthroat trout. Long-term operations of the Costilla Reservoir and Dam have channelized the Rio Costilla, which has become inadequate for holding fish during low-flow conditions and through the winter. The Rio Costilla has become shallow and wide in many spots, and future efforts to re-establish self-sustaining populations of Rio Grande cutthroat trout may not be successful without active management. Since 2001, Rio Grande cutthroat trout and other native fish population restoration efforts have been ongoing within the upper Rio Costilla watershed. Restoration efforts in this section of the Rio Costilla have included the construction of the Rio Costilla terminal fish barrier in October 2016. -

RFP No. 212F for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub

1 RFP No. 212f for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub Final Report Contributing authors: David S. Ruppel, V. Alex Sotola, Ozlem Ablak Gurbuz, Noland H. Martin, and Timothy H. Bonner Addresses: Department of Biology, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas 78666 (DSR, VAS, NHM, THB) Kirkkonaklar Anatolian High School, Turkish Ministry of Education, Ankara, Turkey (OAG) Principal investigators: Timothy H. Bonner and Noland H. Martin Email: [email protected], [email protected] Date: July 31, 2017 Style: American Fisheries Society Funding sources: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Turkish Ministry of Education- Visiting Scholar Program (OAG) Summary Four hundred mesohabitats were sampled from 36 sites and 20 reaches within the upper Red River drainage from September 2015 through September 2016. Fishes (N = 36,211) taken from the mesohabitats represented 14 families and 49 species with the most abundant species consisting of Red Shiner Cyprinella lutrensis, Red River Shiner Notropis bairdi, Plains Minnow Hybognathus placitus, and Western Mosquitofish Gambusia affinis. Red River Pupfish Cyprinodon rubrofluviatilis (a species of greatest conservation need, SGCN) and Plains Killifish Fundulus zebrinus were more abundant within prairie streams (e.g., swift and shallow runs with sand and silt substrates) with high specific conductance. Red River Shiner (SGCN), Prairie Chub Macrhybopsis australis (SGCN), and Plains Minnow were more abundant within prairie 2 streams with lower specific conductance. The remaining 44 species of fishes were more abundant in non-prairie stream habitats with shallow to deep waters, which were more common in eastern tributaries of the upper Red River drainage and Red River mainstem. Prairie Chubs comprised 1.3% of the overall fish community and were most abundant in Pease River and Wichita River. -

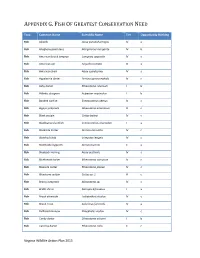

Fish of Greatest Conservation Need

APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Name Scientific Name Tier Opportunity Ranking Fish Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus IV a Fish Allegheny pearl dace Margariscus margarita IV b Fish American brook lamprey Lampetra appendix IV c Fish American eel Anguilla rostrata III a Fish American shad Alosa sapidissima IV a Fish Appalachia darter Percina gymnocephala IV c Fish Ashy darter Etheostoma cinereum I b Fish Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus I b Fish Banded sunfish Enneacanthus obesus IV c Fish Bigeye jumprock Moxostoma ariommum III c Fish Black sculpin Cottus baileyi IV c Fish Blackbanded sunfish Enneacanthus chaetodon I a Fish Blackside darter Percina maculata IV c Fish Blotched chub Erimystax insignis IV c Fish Blotchside logperch Percina burtoni II a Fish Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis IV a Fish Bluebreast darter Etheostoma camurum IV c Fish Blueside darter Etheostoma jessiae IV c Fish Bluestone sculpin Cottus sp. 1 III c Fish Brassy Jumprock Moxostoma sp. IV c Fish Bridle shiner Notropis bifrenatus I a Fish Brook silverside Labidesthes sicculus IV c Fish Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis IV a Fish Bullhead minnow Pimephales vigilax IV c Fish Candy darter Etheostoma osburni I b Fish Carolina darter Etheostoma collis II c Virginia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Fish Carolina fantail darter Etheostoma brevispinum IV c Fish Channel darter Percina copelandi III c Fish Clinch dace Chrosomus sp. cf. saylori I a Fish Clinch sculpin Cottus sp. 4 III c Fish Dusky darter Percina sciera IV c Fish Duskytail darter Etheostoma percnurum I a Fish Emerald shiner Notropis atherinoides IV c Fish Fatlips minnow Phenacobius crassilabrum II c Fish Freshwater drum Aplodinotus grunniens III c Fish Golden Darter Etheostoma denoncourti II b Fish Greenfin darter Etheostoma chlorobranchium I b Fish Highback chub Hybopsis hypsinotus IV c Fish Highfin Shiner Notropis altipinnis IV c Fish Holston sculpin Cottus sp. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Aquatic Fish Report

Aquatic Fish Report Acipenser fulvescens Lake St urgeon Class: Actinopterygii Order: Acipenseriformes Family: Acipenseridae Priority Score: 27 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Gobal Rank: G3G4 — Vulnerable (uncertain rank) State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Ouachita Mountains Arkansas Valley South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plains Acipenser fulvescens Lake Sturgeon 362 Aquatic Fish Report Ecobasins Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - Arkansas River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - St. Francis River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - White River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain (Lake Chicot) - Mississippi River Habitats Weight Natural Littoral: - Large Suitable Natural Pool: - Medium - Large Optimal Natural Shoal: - Medium - Large Obligate Problems Faced Threat: Biological alteration Source: Commercial harvest Threat: Biological alteration Source: Exotic species Threat: Biological alteration Source: Incidental take Threat: Habitat destruction Source: Channel alteration Threat: Hydrological alteration Source: Dam Data Gaps/Research Needs Continue to track incidental catches. Conservation Actions Importance Category Restore fish passage in dammed rivers. High Habitat Restoration/Improvement Restrict commercial harvest (Mississippi River High Population Management closed to harvest). Monitoring Strategies Monitor population distribution and abundance in large river faunal surveys in cooperation -

Arkansas River Shiner Management Plan for the Canadian River 2 from U

FINAL - Submitted for Approval Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) Management Plan for the Canadian River From U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith, Texas © Konrad Schmidt Canadian River Municipal Water Authority June 2005 Arkansas River Shiner Management Plan for the Canadian River 2 from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) Management Plan for the Canadian River from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith, Texas This management plan is a cooperative effort between various local, state, and federal entities. Funding for this plan was provided by the Canadian River Municipal Water Authority. Suggested citation: Canadian River Municipal Water Authority – 2005 – Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) Management Plan for the Canadian River from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith, Texas Preparation of this Plan was accomplished by John C. Williams, acting as Special Advisor under contract to CRMWA. Technical review was provided by Rod Goodwin, Wildlife Biologist and Head of the Water Quality Division of CRMWA. Editorial review was performed by Jolinda Brumley. Cover photograph: Arkansas River Shiner by Ken Collins, USFWS Arkansas River Shiner Management Plan for the Canadian River 3 from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith Table of Contents Introduction and Background …………………………………………………………7 Species Biology ...................................................................................................................9 -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist WATER INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 0908 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 8 IBI sample collection ............................................. 8 Habitat measures............................................... 10 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 15 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 19 Designation of guilds....................................... 20 Results and discussion................................................ 22 Sampling sites and collection results . 22 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 41 1. Number of native species ................................ -

Kansas Stream Fishes

A POCKET GUIDE TO Kansas Stream Fishes ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ By Jessica Mounts Illustrations © Joseph Tomelleri Sponsored by Chickadee Checkoff, Westar Energy Green Team, Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism, Kansas Alliance for Wetlands & Streams, and Kansas Chapter of the American Fisheries Society Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Fish Anatomy • 3 • Species Accounts: Sturgeons (Family Acipenseridae) • 4 ■ Shovelnose Sturgeon • 5 ■ Pallid Sturgeon • 6 Minnows (Family Cyprinidae) • 7 ■ Southern Redbelly Dace • 8 ■ Western Blacknose Dace • 9 ©Ryan Waters ■ Bluntface Shiner • 10 ■ Red Shiner • 10 ■ Spotfin Shiner • 11 ■ Central Stoneroller • 12 ■ Creek Chub • 12 ■ Peppered Chub / Shoal Chub • 13 Plains Minnow ■ Silver Chub • 14 ■ Hornyhead Chub / Redspot Chub • 15 ■ Gravel Chub • 16 ■ Brassy Minnow • 17 ■ Plains Minnow / Western Silvery Minnow • 18 ■ Cardinal Shiner • 19 ■ Common Shiner • 20 ■ Bigmouth Shiner • 21 ■ • 21 Redfin Shiner Cover Photo: Photo by Ryan ■ Carmine Shiner • 22 Waters. KDWPT Stream ■ Golden Shiner • 22 Survey and Assessment ■ Program collected these Topeka Shiner • 23 male Orangespotted Sunfish ■ Bluntnose Minnow • 24 from Buckner Creek in Hodgeman County, Kansas. ■ Bigeye Shiner • 25 The fish were catalogued ■ Emerald Shiner • 26 and returned to the stream ■ Sand Shiner • 26 after the photograph. ■ Bullhead Minnow • 27 ■ Fathead Minnow • 27 ■ Slim Minnow • 28 ■ Suckermouth Minnow • 28 Suckers (Family Catostomidae) • 29 ■ River Carpsucker • -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................