The Politics of Hudud Law Implementation in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

Senarai Penuh Calon Majlis Tertinggi Bagi Pemilihan Umno 2013 Bernama 7 Oct, 2013

Senarai Penuh Calon Majlis Tertinggi Bagi Pemilihan Umno 2013 Bernama 7 Oct, 2013 KUALA LUMPUR, 7 Okt (Bernama) -- Berikut senarai muktamad calon Majlis Tertinggi untuk pemilihan Umno 19 Okt ini, bagi penggal 2013-2016 yang dikeluarkan Umno, Isnin. Pengerusi Tetap 1. Tan Sri Badruddin Amiruldin (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Timbalan Pengerusi Tetap 1. Datuk Mohamad Aziz (Penyandang) 2. Ahmad Fariz Abdullah 3. Datuk Abd Rahman Palil Presiden 1. Datuk Seri Mohd Najib Tun Razak (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Timbalan Presiden 1. Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Naib Presiden 1. Datuk Seri Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi (Penyandang) 2. Datuk Seri Hishammuddin Tun Hussein (Penyandang) 3. Datuk Seri Mohd Shafie Apdal (Penyandang) 4. Tan Sri Mohd Isa Abdul Samad 5. Datuk Mukhriz Tun Dr Mahathir 6. Datuk Seri Mohd Ali Rustam Majlis Tertinggi: (25 Jawatan Dipilih) 1. Datuk Seri Shahidan Kassim (Penyandang/dilantik) 2. Datuk Shamsul Anuar Nasarah 3. Datuk Dr Aziz Jamaludin Mhd Tahir 4. Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob (Penyandang) 5. Datuk Raja Nong Chik Raja Zainal Abidin (Penyandang/dilantik) 6. Tan Sri Annuar Musa 7. Datuk Zahidi Zainul Abidin 8. Datuk Tawfiq Abu Bakar Titingan 9. Datuk Misri Barham 10. Datuk Rosnah Abd Rashid Shirlin 12. Datuk Musa Sheikh Fadzir (Penyandang/dilantik) 13. Datuk Seri Ahmad Shabery Cheek (Penyandang) 4. Datuk Ab Aziz Kaprawi 15. Datuk Abdul Azeez Abdul Rahim (Penyandang) 16. Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed 17. Datuk Sohaimi Shahadan 18. Datuk Seri Idris Jusoh (Penyandang) 19. Datuk Seri Mahdzir Khalid 20. Datuk Razali Ibrahim (Penyandang/dilantik) 21. Dr Mohd Puad Zarkashi (Penyandang) 22. Datuk Halimah Mohamed Sadique 23. -

Politik Dimalaysia Cidaip Banyak, Dan Disini Sangkat Empat Partai Politik

122 mUah Vol. 1, No.I Agustus 2001 POLITICO-ISLAMIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA IN 1999 By;Ibrahim Abu Bakar Abstrak Tulisan ini merupakan kajian singkat seJdtar isu politik Islam di Malaysia tahun 1999. Pada Nopember 1999, Malaysia menyelenggarakan pemilihan Federal dan Negara Bagian yang ke-10. Titik berat tulisan ini ada pada beberapa isupolitik Islamyang dipublikasikandi koran-koran Malaysia yang dilihat dari perspektifpartai-partaipolitik serta para pendukmgnya. Partai politik diMalaysia cidaip banyak, dan disini Sangkat empat partai politik yaitu: Organisasi Nasional Malaysia Bersatu (UMNO), Asosiasi Cina Ma laysia (MCA), Partai Islam Se-Malaysia (PMIP atau PAS) dan Partai Aksi Demokratis (DAP). UMNO dan MCA adalah partai yang berperan dalam Barisan Nasional (BA) atau FromNasional (NF). PASdan DAP adalah partai oposisipadaBarisanAltematif(BA) atau FromAltemattf(AF). PAS, UMNO, DAP dan MCA memilikipandangan tersendiri temang isu-isu politik Islam. Adanya isu-isu politik Islam itu pada dasamya tidak bisa dilepaskan dari latar belakang sosio-religius dan historis politik masyarakat Malaysia. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ ^ <•'«oJla 1^*- 4 ^ AjtLtiLl jS"y Smi]?jJI 1.^1 j yLl J J ,5j^I 'jiil tJ Vjillli J 01^. -71 i- -L-Jl cyUiLLl ^ JS3 i^LwSr1/i VjJ V^j' 0' V oljjlj-l PoUtico-Islnndc Issues bi Malays bi 1999 123 A. Preface This paper is a short discussion on politico-Islamic issues in Malaysia in 1999. In November 1999 Malaysia held her tenth federal and state elections. The paper focuses on some of the politico-Islamic issues which were pub lished in the Malaysian newsp^>ers from the perspectives of the political parties and their leaders or supporters. -

July-December, 2010 International Religious Freedom Report » East Asia and Pacific » Malaysia

Malaysia Page 1 of 12 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » International Religious Freedom » July-December, 2010 International Religious Freedom Report » East Asia and Pacific » Malaysia Malaysia BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR July-December, 2010 International Religious Freedom Report Report September 13, 2011 The constitution protects freedom of religion; however, portions of the constitution as well as other laws and policies placed some restrictions on religious freedom. The constitution gives the federal and state governments the power to "control or restrict the propagation of any religious doctrine or belief among persons professing the religion of Islam." The constitution also defines ethnic Malays as Muslim. Civil courts generally ceded authority to Sharia (Islamic law) courts on cases concerning conversion from Islam, and Sharia courts remained reluctant to allow for such conversions. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the government during the reporting period. Muslims generally may not legally convert to another religion, although members of other religions may convert to Islam. Officials at the federal and state government levels oversee Islamic religious activities, and sometimes influence the content of sermons, use mosques to convey political messages, and prevent certain imams from speaking at mosques. The government maintains a dual legal system, whereby Sharia courts rule on religious and family issues involving Muslims and secular courts rule on other issues pertaining to both Muslims and the broader population. Government policies promoted Islam above other religions. Minority religious groups remained generally free to practice their beliefs; however, over the past several years, many have expressed concern that the civil court system has gradually ceded jurisdictional control to Sharia courts, particularly in areas of family law involving disputes between Muslims and non-Muslims. -

THERE's "INVISIBLE HANDS" in DY PRESIDENT's CONTEST, SAYS JOHARI (Bernama 14/08/1998)

14 AUG 1998 PBB-Contest THERE'S "INVISIBLE HANDS" IN DY PRESIDENT'S CONTEST, SAYS JOHARI KUCHING, Aug 14 (Bernama) -- State Industrial Development Minister Datuk Abang Johari Tun Openg said today there are "invisible hands" involved in the the three-cornered contest for the deputy presidency of the Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB) at the party polls on Aug 28. Abang Johari is challenging two other PBB leaders, incumbent deputy president Datuk Abang Abu Bakar Mustapha and state minister Datuk Adenan Satem in the first such contest for the post in 12 years. "I am contesting not only against my good friend Datuk Adenan Satem but also invisible hands who are financially strong but dare not come out to contest for the post" he told reporters here. Both Abang Johari and Adenan are party vice presidents. Adenan, the Agriculture and Food Industries minister, received 32 nominations for the post, Abang Johari 14 nominations while Abang Abu Bakar managed to obtain only one nomination. Abang Johari appeared emotional at the news conference when he talked of the tactics used by the "financially strong invisible hands" to influence the outcome of the contest for the party's No. 2 post. Before the start of the news conference, Abang Johari asked: " Where's Borneo Post....it's no point if only the Sarawak Tribune and Utusan Sarawak are present". The Borneo Post is regarded here as the more "independent" of Sarawak newspapers and is popular for publishing dissenting views from members of the ruling parties and as well as the opposition. Abang Johari spoke of tactics being used by the "invisible hands" to influence the outcome of the polls, including by spreading word that because Adenan had received a nomination from the Asajaya division headed by party president and Chief Minister Tan Sri Abdul Taib Mahmud, he (Adenan) had Taib's backing. -

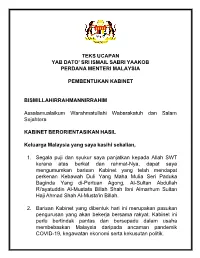

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

Should Qisas Be Considered a Form of Restorative Justice?

UC Berkeley Berkeley Journal of Middle Eastern & Islamic Law Title Restorative Justice in Islam: Should Qisas Be Considered a Form of Restorative Justice? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0mn7f78c Journal Berkeley Journal of Middle Eastern & Islamic Law, 4(1) Author Hascall, Susan C. Publication Date 2011-04-01 DOI 10.15779/Z385P40 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN ISLAM Restorative Justice in Islam: Should Qisas Be Considered a Form of Restorative Justice? Susan C. Hascall* INTRODUCTION The development of criminal punishments in the West is a subject of interest for scholars in various fields.1 One of the foundational ideas has been that the movement away from corporal punishment to other forms of punishment, such as imprisonment, has been an improvement. But, such ideas have not gone unquestioned. In Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison, Michel Foucault asserts that the movement away from the punishment of the body and towards the imprisonment of the body through the widespread institution of the prison has resulted in an even more heinous form of punishment: the punishment of the soul.2 In addition, Foucault contends that the focus on rehabilitation in prisons encourages criminality.3 Although he does not directly advocate restorative justice ideas, his criticism of the prison system has given rise * Assistant Professor of Law, Duquesne University, B.A. Texas A&M University, M.A. The Wichita State University, J.D. Washburn University. The author would like to thank her research assistant, Carly Wilson, for all her help with this article. -

Trends in Southeast Asia

ISSN 0219-3213 2016 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia THE EXTENSIVE SALAFIZATION OF MALAYSIAN ISLAM AHMAD FAUZI ABDUL HAMID TRS9/16s ISBN 978-981-4762-51-9 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 762519 Trends in Southeast Asia 16-1461 01 Trends_2016-09.indd 1 29/6/16 4:52 PM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) was established in 1968. It is an autonomous regional research centre for scholars and specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia. The Institute’s research is structured under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS) and Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and through country- based programmes. It also houses the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), Singapore’s APEC Study Centre, as well as the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and its Archaeology Unit. 16-1461 01 Trends_2016-09.indd 2 29/6/16 4:52 PM 2016 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia THE EXTENSIVE SALAFIZATION OF MALAYSIAN ISLAM AHMAD FAUZI ABDUL HAMID 16-1461 01 Trends_2016-09.indd 3 29/6/16 4:52 PM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2016 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. The author is wholly responsible for the views expressed in this book which do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher. -

The Theory of Punishment in Islamic Law a Comparative

THE THEORY OF PUNISHMENT IN ISLAMIC LAW A COMPARATIVE STUDY by MOHAMED 'ABDALLA SELIM EL-AWA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Law March 1972 ProQuest Number: 11010612 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010612 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 , ABSTRACT This thesis deals with the theory of Punishment in Islamic law. It is divided into four ch pters. In the first chapter I deal with the fixed punishments or Mal hududrl; four punishments are discussed: the punishments for theft, armed robbery, adultery and slanderous allegations of unchastity. The other two punishments which are usually classified as "hudud11, i.e. the punishments for wine-drinking and apostasy are dealt with in the second chapter. The idea that they are not punishments of "hudud11 is fully ex- plained. Neither of these two punishments was fixed in definite terms in the Qurfan or the Sunna? therefore the traditional classification of both of then cannot be accepted. -

Dan Tuan Guru Haji Abdul Hadi Awang (TGHH)

AL-BASIRAH Volume 10, No 2, pp. 17-36, Dec 2020 AL-BASIRAH البصرية Journal Homepage: https://ejournal.um.edu.my/index.php/ALBASIRAH Aliran Islah Dalam Tafsir al-Qur’ān: Analisis Terhadap Elemen Pemikiran Islah Tuan Guru Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat (TGNA) dan Tuan Guru Haji Abdul Hadi Awang (TGHH) Mohd Ridwan Razali1 Mustaffa Abdullah2 Mohd Muhiden Abd Rahman3 Mohamad Azrien Mohamed Adnan4 ABSTRAK Kajian ini adalah kajian kualitatif yang menumpukan kaedah analisis dokumen. Didapati kedua-dua tokoh yang terlibat dalam kajian ini dikenali dalam oleh masyarakat Islam di Malaysia sebagai ahli politik. Bahkan tidak ramai yang mengenali mereka berdua sebagai antara ulama tersohor yang giat menyebarkan dakwah kepada masyarakat Islam melalui kuliah-kuliah agama dan penghasilan karya-karya dalam bidang tafsir al- Quran. Analisis kajian menunjukkan kedua-dua tokoh tersebut cenderung mentafsirkan ayat-ayat al-Quran mengikut aliran islah. Hal ini dapat dikenal pasti melalui penelitian yang mendalam terhadap ayat-ayat al- Quran yang terpilih yang ditafsirkan oleh kedua-dua tokoh tersebut dengan berdasarkan bentuk-bentuk islah yang dicadangkan oleh Muhammad ‘Abd al-‘Azīm al-Zarqānī. Hasil daripada analisis kajian menunjukkan kebanyakan ayat-ayat al-Quran yang ditasfirkan oleh kedua- dua tokoh tersebut banyak menyentuh keenam-enam bentuk-bentuk islah yang dicadangkan oleh al-Zarqānī iaitu melibatkan elemen akidah (Iṣlāḥ al-‘Aqā'id), ibadat (Iṣlāḥ al-'Ibādah), akhlak (Iṣlāḥ al-Akhlāq), pengurusan harta (Iṣlāḥ al-MāI), politik (Iṣlāḥ al-Siyāsah) dan kemasyarakatan (Iṣlāḥ al-Ijtimā'). Kata kunci: Tafsir al-Qur’ān, Pemikiran Islah, Tuan Guru Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat, Tuan Guru Haji Abdul Hadi Awang 1 Calon sarjana Usuluddin di Jabatan al-Quran dan al-Hadith, Akademi Pengajian Islam Universiti Malaya. -

Actress with a Big Heart

20% jump Double in clinical blow for TELLING IT AS IT IS page waste page jobseeker 2 3 INSIDE ON WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 4, 2020 No. 7652 PP 2644/12/2012 (031195) www.thesundaily.my FOOD FOR THOUGHT ... A police officer feeds a cat found loitering outside Plaza Hentian Kajang yesterday while patrolling the complex, which is now under an enhanced movement control order. EPF lifeline? █ BY ALISHA NUR MOHD NOOR [email protected] oDebate hots up over proposal to ETALING JAYA: The proposal to allow employees to dip into their allow withdrawal from Account 1 retirement fund has turned into a debate of meeting short-term needs such as medical fees or to meet their immediate financial Ppecuniary needs versus long-term financial purchase a house. needs,” he told theSun yesterday. security. Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin “This is better than a one-off Unions are all for giving workers access Yassin had said earlier that more people withdrawal that can have a to their Employees Provident Fund (EPF) were seeking the green light to withdraw negative impact on overall Account 1 but employers have warned that from Account 1 of their EPF savings. dividends,” he added. such a move could be devastating for the However, he said, it would be difficult In May, the EPF approved country’s future. to implement given that the government applications from 3.5 The Malaysian Trades Union Congress has already disbursed billions in cash million contributors to (MTUC) has suggested that cash-strapped aid. withdraw RM500 each from EPF contributors be allowed a monthly Halim conceded that it is a tough their Account 2 under the i- withdrawal from their Account 1 savings to decision for EPF to make given that it Lestari scheme. -

Political Development As a Factor for Election of Young Legislative Candidates in the 2019 General Election in Jambi Province

Political Development as a Factor for Election of Young Legislative Candidates in the 2019 General Election in Jambi Province Dori Efendi 1, Nopyandri 2 {[email protected] 1} Universitas Jambi, Indonesia 1 Universitas Jambi, Indonesia 2 Abstract. In the democracy era every candidate has the oportunity to be elected in the General Election constestation. The electability of this young legislative candidate can be accessed through political development. This is because political development in Indonesia goes to the stage of “civil administration”, namely political progress and order. This research discusses how to develop politics as a major factor in the election of young legislative candidates in the 2019 elections and how to get them elected? This article answers these questions. Presupposition that is built to answer the above questions that is the strategy of young legislative candidates in building image, popularity and good personal electability will attract people to vote for them and succeed in attracting the sympathy of novice voters to vote for them. Their election in this election is also a representation of increasing political education, maturity of voters and more mature democracy. Keywords: Political Development, Young Legislative Candidates, 2019 Election. 1 Introduction After the new order, Indonesia politics was marked by many changes. One of them was the simultaneous general election which covered the election of the President, the Regional Representative Board (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah (DPD), the House of People’s