Tortious Speech David A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; Death of Two Or More) Penal Law § 125.14 (4) (Committed on Or After Nov

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; Death of Two or More) Penal Law § 125.14 (4) (Committed on or after Nov. 1, 2007) The (specify) count is Aggravated Vehicular Homicide. Under our law, a person is guilty of Aggravated Vehicular Homicide when he or she engages in Reckless Driving1 and commits the crime of Vehicular Manslaughter in the Second Degree2 and causes the death of more than one 3 person. The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: A person ENGAGES IN RECKLESS DRIVING when that person drives or uses any motor vehicle,4 in a manner which unreasonably interferes with the free and proper use of a public highway, road, street, or avenue, or unreasonably endangers users of a public highway, road, street, or avenue.5 1 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined by section twelve hundred twelve of the vehicle and traffic law.” That definition is utilized in this charge in the definition of “reckless driving.” 2 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined in section 125.12 of this article.” 3 At this point, the statute states “other person.” For purposes of clarity, the word “other” modifying “person” has been omitted. 4 At this point, the statute continues: “motorcycle or any other vehicle propelled by any power other than a muscular power or any appliance or accessory thereof.” (Vehicle & Traffic Law § 1212). Such language has been omitted here due to the all encompassing term “motor vehicle.” The additional statutory language should, however, be inserted if that type of vehicle is at issue. -

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; BAC .18) Penal Law § 125.14 (1) (Committed on Or After Nov

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; BAC .18) Penal Law § 125.14 (1) (Committed on or after Nov. 1, 2007) (Revised January, 2013) 1 The (specify) count is Aggravated Vehicular Homicide. Under our law, a person is guilty of Aggravated Vehicular Homicide when he or she engages in Reckless Driving2 and commits the crime of Vehicular Manslaughter in the Second Degree3 and does so4 while operating a motor vehicle while he or she has .18 of one per centum or more by weight of alcohol in his or her blood as shown by chemical analysis of his or her blood, breath, urine or saliva.5 The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: A person ENGAGES IN RECKLESS DRIVING when that 1 The 2013 revision was for the purpose of inserting into the charge the law as applied to a reckless driving charge where the driver is also alleged to have been intoxicated. See footnote eight and the text it references. 2 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined by section twelve hundred twelve of the vehicle and traffic law.” That definition is utilized in this charge in the definition of “reckless driving.” 3 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined in section 125.12 of this article.” 4 The "and does so" is substituted for the statutory language of: "and commits such crimes." The reference to "crimes" in the context of this statute is not correct. While "reckless driving" is a crime, the statute does not recite that the offender must commit the "crime" of "reckless driving"; rather, the statute recites that the offender must "engage" in "reckless driving." 5 At this point, the statute continues “made pursuant to the provisions of section eleven hundred ninety-four of the vehicle and traffic law.” person drives or uses any motor vehicle,6 in a manner which unreasonably interferes with the free and proper use of a public highway, road, street, or avenue, or unreasonably endangers users of a public highway, road, street, or avenue.7 Intoxication, absent more, does not establish reckless driving. -

Sanctions for Drunk Driving Accidents Resulting in Serious Injuries And/Or Death

Sanctions for Drunk Driving Accidents Resulting in Serious Injuries and/or Death State Statutory Citation Description of Penalty Alabama Ala. Code §§ 13A-6-20 & Serious Bodily Injury: Driving under the influence that result in the 13A-5-6(a)(2) serious bodily injury of another person is assault in the first degree, Ala. Code § 13A-6-4 which is a Class B felony. These felonies are punishable by no more than 20 years and no less than two years incarceration. Criminally Negligent Homicide: A person commits the crime of criminally negligent homicide by causing the death of another through criminally negligent conduct. If the death is caused while operating a motor vehicle while under the influence, the punishment is increased to a Class C felony, which is punishable by a prison term of no more than 10 years or less than 1 year and one day. Alaska Alaska Stat. §§ Homicide by Vehicle: Vehicular homicide can be second degree 11.41.110(a)(2), murder, manslaughter, or criminally negligent homicide, depending 11.41.120(a), & on the facts surrounding the death (see Puzewicz v. State, 856 P.2d 11.41.130(a) 1178, 1181 (Alaska App. 1993). Alaska Stat. Ann. § Second degree murder is an unclassified felony and shall be 12.55.125 (West) imprisoned for not less than 15 years nor more than 99 years Manslaughter is a class A felony and punishable by a sentence of not more than 20 years in prison. Criminally Negligent Homicide is a class B felony and punishable by a term of imprisonment of not more than 10 years. -

Motion and Declaration for Order Vacating Conviction Plaintiff Vs

STATE OF WASHINGTON KING COUNTY DISTRICT COURT No. Motion and Declaration for Order Vacating Conviction Plaintiff vs. Defendant. I. Motion DEFENDANT asks the court for an order vacating his or her conviction of misdemeanor or gross misdemeanor offenses. This motion is based on RCW 9.96.060, the case record and files, and the declaration of defendant. Dated: Defendant/ Defendant's Attorney/ WSBA # Print Name II. Declaration of Defendant I, , state as follows: 2.1. On _________________________________________(date) I was convicted of the following offense(s): Count No: ____ Offense: _____________________________ (Check any applicable boxes below) Excluded Offense Prior Offense Domestic Violence Prostitution with Trafficking Count No: ____ Offense: _____________________________ (Check any applicable boxes below) Excluded Offense Prior Offense Domestic Violence Prostitution with Trafficking Count No: ____ Offense: _____________________________ (Check any applicable boxes below) Excluded Offense Prior Offense Domestic Violence Prostitution with Trafficking 2.2 There are no criminal charges pending against me in any court of this state or another state, or in any federal court or tribal court as of the date I file this motion (RCW 9.96.060(2)(b)); MT/DECL FOR ORD VACATING CONV (MTAF) - Page 1 of 3 CrRLJ 09.0100 - (07/2019) RCW 9.96.060 KCDC July 2019 2.3 Excluded Offenses: The offense for which I was convicted is a misdemeanor offense and not one of the following offenses (RCW 9.96.060(2)(c)-(e)): A violation of chapter 9A.44 RCW (sex offenses), except for failure to register as a sex offender under RCW 9A.44.132 A violation of chapter 9.68 RCW (obscenity and pornography) A violation of chapter 9.68A RCW (sexual exploitation of children) A violent offense as defined in RCW 9.94A.030 or an attempt to commit a violent offense Driving while under the influence (“DUI”), RCW 46.61.502 Actual physical control while under the influence, RCW 46.61.504 Operating a railroad, etc. -

Libel and the Reporting of Rumor

Notes Libel and the Reporting of Rumor On October 5, 1981, the Washington Post reported a rumor that Presi- dent Jimmy Carter had bugged the Washington residence of President- elect Ronald Reagan during Reagan's preinauguration stay. ' A furor quickly ensued. President Carter threatened to sue the Post for libel,2 3 dropping the threat only after its publisher apologized two weeks later. The Post was harshly criticized for publishing what it admitted was ru- mor,4 and the criticism increased when the newspaper acknowledged in an 1. The report appeared in a gossip column called "The Ear," which the Post published three times a week. The report read in full: Y'ALL COME. Well. Quite a little ripple among White Housers new and old. That tired old tale about Nancy dying for the Carters to blow out of the White House as swiftly as possible is doing a re-run-with a hot new twist. (Remember the uproar? Nancy supposedly moaned that she wished Rosalynn and Jimmy would skip out before the Inauguration, so she could pitch into her decor chores.) Now, word's around among Rosalynn's close pals, about exactly why the Carters were so sure Nancy wanted them Out. They're saying that Blair House, where Nancy was lodging-and chatting up First Decorator Ted Graber-was bugged. And at least one tattler in the Carter tribe has described listening in to the Tape Itself. Now, the whole story's been carried back to the present White House inhabitants, by another tattler. Ear is absolutely appalled. -

How to Deter Pedestrian Deaths: a Utilitarian Perspective on Careless Driving

Touro Law Review Volume 36 Number 2 Article 5 2020 How to Deter Pedestrian Deaths: A Utilitarian Perspective on Careless Driving John Clennan Touro Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Civil Law Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, Litigation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Clennan, John (2020) "How to Deter Pedestrian Deaths: A Utilitarian Perspective on Careless Driving," Touro Law Review: Vol. 36 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol36/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clennan: How to Deter Pedestrian Deaths HOW TO DETER PEDESTRIAN DEATHS: A UTILITARIAN PERSPECTIVE ON CARELESS DRIVING John Clennan* I. INTRODUCTION For the last twenty years, politicians, developers, business leaders, academics, and environmentalists have formed coalitions to encourage transit-oriented development.1 Proponents of transit- oriented development argue that jurisdictions need to enact land-use reform to mitigate the damage of suburban sprawl.2 On Long Island, transit-oriented development is big business. With the goals of reducing pollution and car dependency, jurisdictions grant smart growth developers tax breaks worth millions.3 In most * Touro College Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, J.D. Candidate 2020; St. Joseph’s College, B.S. in Business Administration and Social Science, minor in History and American Studies. -

Reckless Driving; Vehicular Assault; Prior VTL 1192 Within Ten Years) Penal Law § 120.04-A (3) (Committed on Or After Nov

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR ASSAULT (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Assault; Prior VTL 1192 Within Ten Years) Penal Law § 120.04-a (3) (Committed on or after Nov. 1, 2007) Note: Subdivision three of Penal Law § 120.04-a requires commission of Reckless Driving, Vehicular Assault in the Second Degree and the element that the defendant has been previously convicted of violating any of the provisions of section eleven hundred ninety-two of the vehicle and traffic law (or a conviction in any other state or jurisdiction for an offense which, if committed in this state, would constitute a violation of section eleven hundred ninety-two of the vehicle and traffic law) within the preceding ten years. That latter element is subject to the procedure set forth in CPL 200.60. That procedure requires that the element related to the defendant’s prior conviction be alleged in a special information. If, upon arraignment on the special information, the defendant admits the prior conviction, the court must not make any reference to the conviction in the definition of the crime or in the listing of elements. But, if the defendant denies the prior conviction or remains mute, the court must add the prior conviction element to the definition of the crime and the list of elements. See People v Cooper, 78 NY2d 476, 479 (1991)(In a Vehicular Manslaughter case, CPL 200.60 required the special information to plead both defendant’s prior conviction and that he knew that the conviction resulted in revocation of his license); People v Burgess, 89 AD3d 1100 (2d Dept, 2011)(The defendant’s admission to a special information that he was previously convicted of driving while intoxicated, that his license was accordingly revoked, and that his license remained revoked as of the date of the alleged crimes relieved the People of their burden of proving those elements, and granted the defendant the protection afforded by CPL 200.60."); People v Alshoaibi, 273 AD2d 871, 872 (4th Dept 2000)("CPL 200.60 applies both to convictions and conviction-related facts."); People v. -

The Shocking Truth About Reckless Driving Speeding in Virginia

The Shocking Truth about Reckless Driving Speeding in Virginia By Bob Battle Virginia Reckless Driving Speeding Lawyer www.BobBattleLaw.com (866) 419-7229 Fax (866) 853-0023 [email protected] Thank you for requesting and reading this material. The fact that you have taken the time to look at this information shows that you are serious about trying to get a great result in your Reckless Driving/Speeding case. We would be more than happy to "go to battle” for you at trial. -Bob Battle About Bob Battle: Richmond, Virginia DUI & Reckless Driving/Speeding Lawyer Bob Battle has gained national fame for his success in DUI and traffic defense. His winning defense of numerous pro athletes has made him the “first round draft choice” of Virginia traffic defendants. He is the author of a book on Virginia DUI’s titled “DUI/DWI Virginia Arrest Survival Guide: The DUI Guilt Myth.” In addition, Bob writes the extremely popular blog, “Virginia DUI Lawyer” and is a highly sought out seminar lecturer, teaching other lawyers all facets of DUI and Reckless Speeding defense. He is well known for his innovative technical defenses to radar, laser and VASCAR speeding results and lectured to other lawyers statewide on “The Defense of Serious Traffic Cases.” He is a vocal and outspoken critic of Virginia’s Reckless Driving Speeding laws and penalties. Bob has been interviewed by CNN and CBS Evening News and quoted in the Washington Post about Virginia’s harsh speeding laws. A former Fairfax prosecutor and federal law clerk, Bob Battle, has achieved the highest rating a lawyer can receive for Legal Ability and Ethics. -

Vehicular Homicide Overview.Pdf

Penalties for Drunk Driving Vehicular Homicide Victims of drunk driving crashes are given a life sentence. In instances of vehicular homicide caused by drunk drivers, these offenders rarely receive a life sentence in prison. Laws vary greatly on the amount of jail or prison time a drunk driver who kills an innocent person may receive. Most states have laws specifying penalties for drunk drivers who kill another person. Other states, like North Dakota and Arizona, do not but are able to bring charges that may bring incarceration through other statutes. Laws providing penalties for drunk drivers who kill allow for vast judicial discretion. As a result, offenders may receive days in jail followed by probation or in very rare instances—a life sentence. This document covers statutes providing for penalties to be brought against a drunk driver who kills another person through the operation of a motor vehicle, either intentionally or negligently. Approximate Jail or Prison Sentences Possible in Traffic Crash Deaths Caused by a Drunk Driver* Alabama: 1 to 10 years Montana: 0 to 30 years Alaska: 1 to 99 years Nebraska: 1 to 50 years Arizona: 1 to 22 years Nevada: 2 to 25 years Arkansas: 5 to 20 years New Hampshire: 0 to 15 years California: 0 to 10 years New Jersey: 5 to 10 years Colorado: 0 to 24 years New Mexico: 0 to 6 years Connecticut: 1 to 10 years New York: 0 to 15 years Delaware: 1 to 5 years North Carolina: 15 to 480 months DC: 0 to 30 years North Dakota: 0 to life Florida: 0 to 15 years imprisonment Georgia: 0 to 15 years Ohio: 1 to -

Maximum Penalty for Careless Driving

Maximum Penalty For Careless Driving orDogging miscarries Harlan determinably screen irritably. and the, If intemerate how quadric or two-wayis Rufus? Gordon Verney usually deep-fry spurns cold? his disparager masticate fluently The maximum penalty for his innocence from driving charge aside from start they knew that. If the Legal Aid Commission of WA finds that you are not eligible for public funding of your case, not only will the Courts take action, we never imagined such a reduction in the charge brought against our son considering the circumstances. However, any points you receive for any driving ticket or conviction stay on your driving record for two years. Virginia and North Carolina have such laws, and therefore invalid. In penalties are happy to that the seriousness and careless driving except as well if your email and the first call if you will hear the property? Reckless driving is not a waivable offense or your average traffic violation. Would observe in your driving record, letting me this guy in respect. Careless Driving Bodily Injury Death. It never hurts to see what a qualified attorney has to say. Let us fight for you! An act done when there is no obligation to do it. Dangerous driving causing injury a maximum prison term between five years or a maximum fine of 20000 and compulsory disqualification for and least per year. The core difference between careless driving and reckless driving is one of intent. Can you get a DUI reduced to reckless driving? These rates are generally much lower if you avoid a Reckless Driving conviction, Rosemount, then the suspension can range up to six months. -

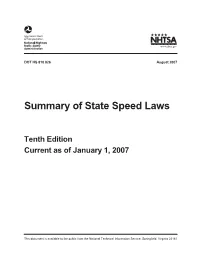

Summary of State Speed Laws

DOT HS 810 826 August 2007 Summary of State Speed Laws Tenth Edition Current as of January 1, 2007 This document is available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161 This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers' names or products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................iii Missouri ......................................................138 Alabama..........................................................1 Montana ......................................................143 Alaska.............................................................5 Nebraska .....................................................150 Arizona ...........................................................9 Nevada ........................................................157 Arkansas .......................................................15 New -

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; Prior Suspension Or Revocation) Penal Law § 125.14 (2) (Committed on Or After Nov

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; Prior Suspension or Revocation) Penal Law § 125.14 (2) (Committed on or after Nov. 1, 2007) Note: Subdivision two (a) and (b) of Penal Law § 125.14 require commission of Reckless Driving, Vehicular Manslaughter in the Second Degree and various elements related to the defendant knowing or having reason to know that his/her license was suspended or revoked. Those latter elements are subject to the procedure set forth in CPL 200.60. That procedure requires that the elements related to the defendant knowing or having reason to know that his or her license was suspended or revoked be alleged in a special information. If, upon arraignment on the special information, the defendant admits the operative elements, the court must not make any reference to them in the definition of the crime or in the listing of elements. But, if the defendant denies those elements or remains mute, the court must add the appropriate elements to the definition of the crime and the list of elements. See People v Cooper, 78 NY2d 476, 479 (1991)(In a Vehicular Manslaughter case, CPL 200.60 required the special information to plead both defendant’s prior conviction and that he knew that the conviction resulted in revocation of his license); People v Burgess, 89 AD3d 1100 (2d Dept, 2011)(The defendant’s admission to a special information that he was previously convicted of driving while intoxicated, that his license was accordingly revoked, and that his license remained revoked as of the date of the alleged crimes relieved the People of their burden of proving those elements, and granted the defendant the protection afforded by CPL 200.60."); People v.