How to Deter Pedestrian Deaths: a Utilitarian Perspective on Careless Driving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; Death of Two Or More) Penal Law § 125.14 (4) (Committed on Or After Nov

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; Death of Two or More) Penal Law § 125.14 (4) (Committed on or after Nov. 1, 2007) The (specify) count is Aggravated Vehicular Homicide. Under our law, a person is guilty of Aggravated Vehicular Homicide when he or she engages in Reckless Driving1 and commits the crime of Vehicular Manslaughter in the Second Degree2 and causes the death of more than one 3 person. The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: A person ENGAGES IN RECKLESS DRIVING when that person drives or uses any motor vehicle,4 in a manner which unreasonably interferes with the free and proper use of a public highway, road, street, or avenue, or unreasonably endangers users of a public highway, road, street, or avenue.5 1 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined by section twelve hundred twelve of the vehicle and traffic law.” That definition is utilized in this charge in the definition of “reckless driving.” 2 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined in section 125.12 of this article.” 3 At this point, the statute states “other person.” For purposes of clarity, the word “other” modifying “person” has been omitted. 4 At this point, the statute continues: “motorcycle or any other vehicle propelled by any power other than a muscular power or any appliance or accessory thereof.” (Vehicle & Traffic Law § 1212). Such language has been omitted here due to the all encompassing term “motor vehicle.” The additional statutory language should, however, be inserted if that type of vehicle is at issue. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of OHIO 2008 STATE of OHIO, Case No. 07

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO 2008 STATE OF OHIO, Case No. 07-2424 Plaintiff-Appellee, On Appeal from the -vs- Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals, Eighth Appellate District MARCUS DAVIS, Court of Appeals Defendant-Appellant Case No. 88895 MEMORANDUM OF AMICUS CURIAE FRANKLIN COUNTY PROSECUTOR RON O'BRIEN IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE STATE OF OHIO'S MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION RON O'BRIEN 0017245 ROBERT L. TOBIK 0029286 Franklin County Prosecuting Attorney Cuyahoga County Public Defender STEVEN L. TAYLOR 0043876 PAUL A. KUZMINS 0074475 (Counsel of Record) (Counsel of Record) Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Assistant Public Defender SETH L. GILBERT 0072929 1200 West Third Street Assistant Prosecuting Attorney 100 Lakeside Place 373 South High Street, 13`h Floor Cleveland, Ohio 44113 Columbus, Ohio 43215 Phone: 216/448-8388 Phone: 614/462-3555 Fax: 614/462-6103 Counsel for Defendant-Appellant E-mail: [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae Franklin County Prosecutor Ron O'Brien WILLIAM D. MASON 0037540 Cuyahoga County Prosecuting Attorney THORIN O. FREEMAN 0079999 (Counsel of Record) Assistant Prosecuting Attorney The Justice Center, 8th Floor 1200 Ontario Street Cleveland, Ohio 44113 Phone: 216/443-7800 Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellee State of Ohio MEMORANDUM OF AMICUS CURIAE FRANKLIN COUNTY PROSECUTOR RON O'BRIEN IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE STATE OF OHIO'S MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION In State v. Colon, 118 Ohio St.3d 26, 2008-Ohio-1624 ("Colon P'), the defendant stood convicted on a robbery charge under R.C. 2911.02(A)(2), alleging that, in attempting or committing a theft offense or fleeing therefrom, defendant attempted, threatened, or actually inflicted physical harm on the victim. -

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; BAC .18) Penal Law § 125.14 (1) (Committed on Or After Nov

AGGRAVATED VEHICULAR HOMICIDE (Reckless Driving; Vehicular Manslaughter; BAC .18) Penal Law § 125.14 (1) (Committed on or after Nov. 1, 2007) (Revised January, 2013) 1 The (specify) count is Aggravated Vehicular Homicide. Under our law, a person is guilty of Aggravated Vehicular Homicide when he or she engages in Reckless Driving2 and commits the crime of Vehicular Manslaughter in the Second Degree3 and does so4 while operating a motor vehicle while he or she has .18 of one per centum or more by weight of alcohol in his or her blood as shown by chemical analysis of his or her blood, breath, urine or saliva.5 The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: A person ENGAGES IN RECKLESS DRIVING when that 1 The 2013 revision was for the purpose of inserting into the charge the law as applied to a reckless driving charge where the driver is also alleged to have been intoxicated. See footnote eight and the text it references. 2 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined by section twelve hundred twelve of the vehicle and traffic law.” That definition is utilized in this charge in the definition of “reckless driving.” 3 At this point, the statute continues: “as defined in section 125.12 of this article.” 4 The "and does so" is substituted for the statutory language of: "and commits such crimes." The reference to "crimes" in the context of this statute is not correct. While "reckless driving" is a crime, the statute does not recite that the offender must commit the "crime" of "reckless driving"; rather, the statute recites that the offender must "engage" in "reckless driving." 5 At this point, the statute continues “made pursuant to the provisions of section eleven hundred ninety-four of the vehicle and traffic law.” person drives or uses any motor vehicle,6 in a manner which unreasonably interferes with the free and proper use of a public highway, road, street, or avenue, or unreasonably endangers users of a public highway, road, street, or avenue.7 Intoxication, absent more, does not establish reckless driving. -

Tortious Speech David A

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 47 | Issue 1 Article 3 Winter 1-1-1990 Tortious Speech David A. Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation David A. Anderson, Tortious Speech, 47 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 71 (1990), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol47/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TORTIOUS SPEECH DAVID A. ANDERSON* When most of the communications torts were developing, it was thought that tortious speech required no constitutional protection. If the speech occurred in advertising, the tort rules of liability were doubly insulated from constitutional attack, because it was also believed that commercial speech required no constitutional protection. The courts and occasionally the leg- islatures developed nonconstitutional rules to adjust between the social, economic, and personal interests protected by these torts and the conflicting values of free speech. Except in defamation, these state law rules are still the dominant means of accommodating these competing interests. Since New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,' however, we have known that the constitution protects some tortious speech. Since the 1970s we have known also that the constitution protects some commercial speech. As a consequence, all the communications torts are now vulnerable to constitu- tional scrutiny. -

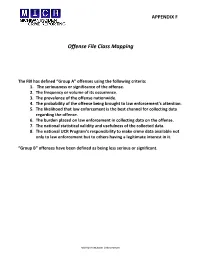

Offense File Class Mapping

APPENDIX F Offense File Class Mapping The FBI has defined “Group A” offenses using the following criteria: 1. The seriousness or significance of the offense. 2. The frequency or volume of its occurrence. 3. The prevalence of the offense nationwide. 4. The probability of the offense being brought to law enforcement’s attention. 5. The likelihood that law enforcement is the best channel for collecting data regarding the offense. 6. The burden placed on law enforcement in collecting data on the offense. 7. The national statistical validity and usefulness of the collected data. 8. The national UCR Program’s responsibility to make crime data available not only to law enforcement but to others having a legitimate interest in it. “Group B” offenses have been defined as being less serious or significant. MICHIGAN INCIDENT CRIME REPORT APPENDIX F Offense File Class Mapping Chart File MICR Offense Group NIBRS Class Description (A or B) Class Description 01000 Sovereignty Group B 90Z All Other 02000 Military Group B 90Z All Other 03000 Immigration Group B 90Z All Other 09001 Murder/Non‐Negligent Manslaughter Group A 09A Murder/Non‐Negligent Manslaughter 09002 Negligent Homicide/Manslaughter Group A 09B Negligent Manslaughter 09003 Negligent Homicide Vehicle/Boat/ Snowmobile/ORV Group B 90Z All Other 09004 Justifiable Homicide Group A 09C Justifiable Homicide 10001 Kidnapping/Abduction Group A 100 Kidnapping/Abduction 10002 Parental Kidnapping Group A 100 Kidnapping/Abduction 11001 Sexual Penetration Penis/Vagina CSC1 Group A 11A Forcible Rape 11002 -

Sanctions for Drunk Driving Accidents Resulting in Serious Injuries And/Or Death

Sanctions for Drunk Driving Accidents Resulting in Serious Injuries and/or Death State Statutory Citation Description of Penalty Alabama Ala. Code §§ 13A-6-20 & Serious Bodily Injury: Driving under the influence that result in the 13A-5-6(a)(2) serious bodily injury of another person is assault in the first degree, Ala. Code § 13A-6-4 which is a Class B felony. These felonies are punishable by no more than 20 years and no less than two years incarceration. Criminally Negligent Homicide: A person commits the crime of criminally negligent homicide by causing the death of another through criminally negligent conduct. If the death is caused while operating a motor vehicle while under the influence, the punishment is increased to a Class C felony, which is punishable by a prison term of no more than 10 years or less than 1 year and one day. Alaska Alaska Stat. §§ Homicide by Vehicle: Vehicular homicide can be second degree 11.41.110(a)(2), murder, manslaughter, or criminally negligent homicide, depending 11.41.120(a), & on the facts surrounding the death (see Puzewicz v. State, 856 P.2d 11.41.130(a) 1178, 1181 (Alaska App. 1993). Alaska Stat. Ann. § Second degree murder is an unclassified felony and shall be 12.55.125 (West) imprisoned for not less than 15 years nor more than 99 years Manslaughter is a class A felony and punishable by a sentence of not more than 20 years in prison. Criminally Negligent Homicide is a class B felony and punishable by a term of imprisonment of not more than 10 years. -

Insufficient Concern: a Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability

Insufficient Concern: A Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability Larry Alexandert INTRODUCTION Most criminal law theorists and the criminal codes on which they comment posit four distinct forms of criminal culpability: purpose, knowl- edge, recklessness, and negligence. Negligence as a form of criminal cul- pability is somewhat controversial,' but the other three are not. What controversy there is concerns how the lines between them should be drawn3 and whether there should be additional forms of criminal culpabil- ity besides these four.' My purpose in this Essay is to make the case for fewer, not more, forms of criminal culpability. Indeed, I shall try to demonstrate that pur- pose and knowledge can be reduced to recklessness because, like reckless- ness, they exhibit the basic moral vice of insufficient concern for the interests of others. I shall also argue that additional forms of criminal cul- pability are either unnecessary, because they too can be subsumed within recklessness as insufficient concern, or undesirable, because they punish a character trait or disposition rather than an occurrent mental state. Copyright © 2000 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Incorporated (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. f Warren Distinguished Professor of Law, University of San Diego. I wish to thank all the participants at the Symposium on The Morality of Criminal Law and its honoree, Sandy Kadish, for their comments and criticisms, particularly Leo Katz and Stephen Morse, who gave me comments prior to the event, and Joshua Dressler, whose formal Response was generous, thoughtful, incisive, and prompt. -

SIMPLIFICATION of CRIMINAL LAW: KIDNAPPING Analysis of Responses to Consultation Paper No

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 200 (Analysis of Responses) SIMPLIFICATION OF CRIMINAL LAW: KIDNAPPING Analysis of Responses to Consultation Paper No 200 29 January 2014 KIDNAPPING: ANALYSIS OF RESPONSES 1.1 This minute analyses the responses to Consultation Paper No 200, Simplification of Criminal Law: Kidnapping. The questions for consultation may be summarised as follows. (1) Whether the offences of false imprisonment and kidnapping, or either of them, should be replaced by statute. (2) Whether “force or fraud” should continue to exist as a separate condition of liability or should be treated simply as evidence of lack of consent. (3) Whether there should be a condition of “lawful excuse”, leaving to the general law the question of what is a lawful excuse. (4) Whether the fault element should be “intention or subjective recklessness”. (5) Whether honest belief in consent should be a complete defence or whether the belief should be reasonable. (6) Whether the new offence or offences should be triable either way. (7) Whether the new offence or offences should take the form of: (a) Model 1: one offence covering all forms of deprivation of liberty; (b) Model 2: separate offences of detention and kidnapping; (c) Model 3: one basic offence of deprivation of liberty and one aggravated offence where any of a list of named factors or intentions is present. THE INDIVIDUAL RESPONSES Anthony Edwards 1.2 Taking the questions in the same order, his responses are as follows. (1) Both offences should be replaced. (2) Force or fraud should be evidence of lack of consent. (3) There should be a condition “without lawful excuse”. -

Ballot Language for Initiative No. 188 (I-188)

BALLOT LANGUAGE FOR INITIATIVE NO. 188 (I-188) INITIATIVE NO. 188 A LAW PROPOSED BY INITIATIVE PETITION I-188 creates the criminal offense of vehicular manslaughter. A person commits the crime of vehicular manslaughter if the person kills a human being or unborn child while operating a vehicle recklessly, carelessly, with depraved indifference, or with gross negligence. A person convicted of vehicular manslaughter could be punished with up to a $50,000 fine, incarceration for up to 20 years, or both. The driver’s license of the convicted person would be suspended for one year either after release from incarceration or upon the person’s sentencing if incarceration is not imposed. I-188 allows a court to order the convicted person to pay child support for each minor child of the deceased person. [] YES ON INITIATIVE I-188 [] NO ON INITIATIVE I-188 THE COMPLETE TEXT OF INITIATIVE NO. 188 (I-188) Be it enacted by the People of the state of Montana: NEW SECTION. Section 1. Vehicular manslaughter. (1) A person commits the offense of vehicular manslaughter if the person: (a) operates a vehicle recklessly or carelessly or with depraved indifference or with gross negligence likely to cause the death of or great bodily harm to another; and (b) the operation of the vehicle results in the killing of a human being or an unborn child by any injury to the mother. (2) A person convicted of vehicular manslaughter is guilty of a felony and shall punished by: (a) a fine in an amount not to exceed $50,000, incarceration for a term not to exceed 20 year, or both; and (b) suspension of the person's driver's license for a period of 1 year to begin upon the person's release from incarceration or upon the person's sentencing if incarceration is not imposed. -

Intoxication and Recklessness 22

INTOXICATION AND RECKLESSNESS I. INTRODUCTION An issue which periodically falls to be determined by the courts is the question of whether or not intoxication is relevant to an issue of recklessness. The pro blem arises when the definition of an offence allows proof of recklessness as a sufficient mens rea. The question is then whether evidence of intoxication can be allowed to negative recklessness. Until the decision of the House of lords in R v Caldwell; 1 recklessness had a more or less fixed meaning in common law which distinguished it from the other states of mind. Generally. it would seem to lie somewhere between "negligence" and "intention" and in its natural sense to imply the conscious and unreasonable running of risk. However, the apparent effect of Caldwell and its sister case R v Lawrence2 (an appeal heard immediately after Caldwell and also involving consideration of a meaning of recklessness) has been to extend the meaning of "recklessness' to include inadvertent negligence. If this is a ,cor rect view of these. cases then. as Professor Glanville Williams has expressed it. "they work a profoundly regrettable change in the criminallaw".3 We can note. at this point. that the general effect of these two cases is to attach a much firmer objective meaning to the concept of recklessness than it has obviously been given in a series of decisions in the English Court of Appeal. As far as intoxication is concerned, the effect of Caldwell is to declare that nearly· all crimes, can beqommitted recklessly and that evidence of voluntary intol(icationvvill not assist to save people charged with these offences from conviction. -

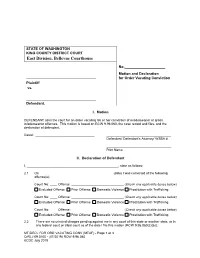

Motion and Declaration for Order Vacating Conviction Plaintiff Vs

STATE OF WASHINGTON KING COUNTY DISTRICT COURT No. Motion and Declaration for Order Vacating Conviction Plaintiff vs. Defendant. I. Motion DEFENDANT asks the court for an order vacating his or her conviction of misdemeanor or gross misdemeanor offenses. This motion is based on RCW 9.96.060, the case record and files, and the declaration of defendant. Dated: Defendant/ Defendant's Attorney/ WSBA # Print Name II. Declaration of Defendant I, , state as follows: 2.1. On _________________________________________(date) I was convicted of the following offense(s): Count No: ____ Offense: _____________________________ (Check any applicable boxes below) Excluded Offense Prior Offense Domestic Violence Prostitution with Trafficking Count No: ____ Offense: _____________________________ (Check any applicable boxes below) Excluded Offense Prior Offense Domestic Violence Prostitution with Trafficking Count No: ____ Offense: _____________________________ (Check any applicable boxes below) Excluded Offense Prior Offense Domestic Violence Prostitution with Trafficking 2.2 There are no criminal charges pending against me in any court of this state or another state, or in any federal court or tribal court as of the date I file this motion (RCW 9.96.060(2)(b)); MT/DECL FOR ORD VACATING CONV (MTAF) - Page 1 of 3 CrRLJ 09.0100 - (07/2019) RCW 9.96.060 KCDC July 2019 2.3 Excluded Offenses: The offense for which I was convicted is a misdemeanor offense and not one of the following offenses (RCW 9.96.060(2)(c)-(e)): A violation of chapter 9A.44 RCW (sex offenses), except for failure to register as a sex offender under RCW 9A.44.132 A violation of chapter 9.68 RCW (obscenity and pornography) A violation of chapter 9.68A RCW (sexual exploitation of children) A violent offense as defined in RCW 9.94A.030 or an attempt to commit a violent offense Driving while under the influence (“DUI”), RCW 46.61.502 Actual physical control while under the influence, RCW 46.61.504 Operating a railroad, etc. -

Crimes Against Property

9 CRIMES AGAINST PROPERTY Is Alvarez guilty of false pretenses as a Learning Objectives result of his false claim of having received the Congressional Medal of 1. Know the elements of larceny. Honor? 2. Understand embezzlement and the difference between larceny and embezzlement. Xavier Alvarez won a seat on the Three Valley Water Dis- trict Board of Directors in 2007. On July 23, 2007, at 3. State the elements of false pretenses and the a joint meeting with a neighboring water district board, distinction between false pretenses and lar- newly seated Director Alvarez arose and introduced him- ceny by trick. self, stating “I’m a retired marine of 25 years. I retired 4. Explain the purpose of theft statutes. in the year 2001. Back in 1987, I was awarded the Con- gressional Medal of Honor. I got wounded many times by 5. List the elements of receiving stolen property the same guy. I’m still around.” Alvarez has never been and the purpose of making it a crime to receive awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, nor has he stolen property. spent a single day as a marine or in the service of any 6. Define forgery and uttering. other branch of the United States armed forces. The summer before his election to the water district board, 7. Know the elements of robbery and the differ- a woman informed the FBI about Alvarez’s propensity for ence between robbery and larceny. making false claims about his military past. Alvarez told her that he won the Medal of Honor for rescuing the Amer- 8.