Reaffirming the Educational Role of Australian Children's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Above: These images appear in an article by Dr Patricia Clarke (see ANHG 93.4.10). Left: Jennie Scott Wilson, c.1888. Centre: Jennie Scott Wilson on her wedding day, 1897. Right: Jennie Scott Griffiths, Brisbane, 2 May 1920. [Papers of Jennie Scott Griffiths, nla.cat-vn1440105] Below: Miscellaneous Receipts, Tickets, Cards and Conference Badges, 1916–1920 [Papers of Jennie Scott Griffiths, nla.cat-vn1440105] AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 93 July 2017 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 September 2017. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 93.1.1 Fairfax Media: job cuts, strike and acquisition proposal Fairfax Media was in the headlines for three big reasons in the first week in May: (1) it announced it was going to cut one-quarter of its metropolitan journalistic staff; (2) its metropolitan journalists went out on strike for an “unprecedented” seven days; and (3) it received a proposal from a private equity firm interested in acquiring its metropolitan assets, principally Domain and its major mastheads, such as the Sydney Morning Herald, Age and Australian Financial Review. -

The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News

Pikkert. Function after Form … The McMaster Journal of Communication Volume 4, Issue 1 2007 Article 6 Function after Form: The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News Owen Pikkert McMaster University Copyright © 2007 by the authors. The McMaster Journal of Communication is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). http://digitalcommons.mcmaster.ca/mjc The McMaster Journal of Communication. Volume 4 [2007], Issue 1, Article 6 Function after Form: The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News Owen Pikkert Abstract This paper analyzes the impact of television news upon political mobilization and awareness. In particular, it places a strong emphasis on the inherent inability of episodic news to form a cognitive framework through which to understand current events. The paper begins with preliminary statements on the significance of television news and describes the limits of the paper’s scope. It then examines the correlation of episodic television news with political cynicism, the trivialization of news content, and the formation of a pro-establishment attitude among viewers. A greater stress is placed upon the way in which television news is presented than upon news content or on the paucity of social capital. In conclusion, an argument is made for the imposition of sound bite quotas, with the desire to counter the handicaps of the episodic medium. KEYWORDS: Episodic, news, television, trivialization, political bias, pro- establishment, political cynicism, television medium, reporting, sound bite, post-structuralism The McMaster Journal of Communication. Volume 4 [2007], Issue 1, Article 6 The McMaster Journal of Communication 2007 Volume 4, Issue 1 Function after Form: The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News Owen Pikkert McMaster University Introduction elevision, as a channel for expression and public debate, is crucial to the health of a democratic state. -

Is the Government Listening? Now That the Uproar and Shouting About Alleged Bias Has Died Down, There Is Only One Issue Paramount for the ABC - Funding

Friends of the ABC (NSW) Inc. qu a rt e r ly news l e t t e r Se ptember 2005 Vol 15, No. 3 in c o rp o rat i n g ba ck g round briefing na tional magaz i n e up d a t e friends of the abc Is the Government listening? Now that the uproar and shouting about alleged bias has died down, there is only one issue paramount for the ABC - funding. The corporation has not been backward putting its case forward - notably the collapse of drama production to just 20 hours per annum. In the Melbourne Age, Director of ABC TV Sandra Levy referred to circumstances as "critical and tragic." around, low-cost end - we've pretty "We have all those important well done everything we can." obligations to indigenous programs, religious programs, science, arts, Costs up children’s programs ... things that the dramatically commercial networks don't, and yet Once the launch pad for great we probably battle along with about Australian drama, revelations that the a quarter of what they spend in a ABC's drama output has dwindled year - the disproportion is massive." from 100 hours four years ago to just Ms Levy's concerns have been 14 hours this year have received a lot echoed by managing director Russell of media attention. Balding and chairman Donald Ms Levy estimates that an hour McDonald, who have spent the past could cost anywhere from $500,000 few weeks publicly lamenting the to $2 million, 10 to 50 times more gravity of the funding crisis. -

ABC TV 2015 Program Guide

2014 has been another fantastic year for ABC sci-fi drama WASTELANDER PANDA, and iview herself in a women’s refuge to shine a light TV on screen and we will continue to build on events such as the JONAH FROM TONGA on the otherwise hidden world of domestic this success in 2015. 48-hour binge, we’re planning a range of new violence in NO EXCUSES! digital-first commissions, iview exclusives and We want to cement the ABC as the home of iview events for 2015. We’ll welcome in 2015 with a four-hour Australian stories and national conversations. entertainment extravaganza to celebrate NEW That’s what sets us apart. And in an exciting next step for ABC iview YEAR’S EVE when we again join with the in 2015, for the first time users will have the City of Sydney to bring the world-renowned In 2015 our line-up of innovative and bold ability to buy and download current and past fireworks to audiences around the country. content showcasing the depth, diversity and series, as well programs from the vast ABC TV quality of programming will continue to deliver archive, without leaving the iview application. And throughout January, as the official what audiences have come to expect from us. free-to-air broadcaster for the AFC ASIAN We want to make the ABC the home of major CUP AUSTRALIA 2015 – Asia’s biggest The digital media revolution steps up a gear in TV events and national conversations. This year football competition, and the biggest football from the 2015 but ABC TV’s commitment to entertain, ABC’s MENTAL AS.. -

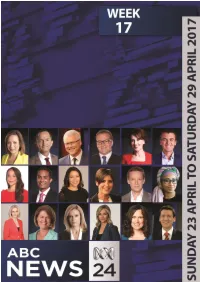

ABC News 24 Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABCNEWS24 Program Guide: National: Week 17 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 23 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 24 April 2017 .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 25 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Wednesday, 26 April 2017 .................................................................................................................................. 17 Thursday, 27 April 2017 ...................................................................................................................................... 20 Friday, 28 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................... 23 Saturday, 29 April 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 26 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 31 2 | P a -

ABC Special Coverage As Garma Festival Turns 20

Media Release: 25 July 2018 ABC special coverage as Garma Festival turns 20 In a special year for the Garma Festival – its 20th anniversary – the ABC is proud to again participate in this iconic event as Official Media Partner, as well as presenting a special programming slate to Australians nationally. The ABC will also assist NITV with its coverage. 2018 Garma will be held from 3-6 August at Gulkula in North-East Arnhem Land. This year’s theme is Yuwalk Lakaraŋa – or truth-telling. ABC Managing Director Michelle Guthrie said: “Garma takes pride of place on the ABC’s national calendar of events. The annual festival is a major celebration of Indigenous culture and conversations and the ABC is proud to play a role in ensuring its success. “The ABC broadcasts live from one of most culturally significant gatherings in Australia so that the message of Garma – this year Yuwalk Lakaraŋa – travels far beyond the sacred Yolngu site. “We have renewed our commitment to Garma this year not only because it brings Indigenous Australians together to talk frankly with each other, but because it helps focus attention on the issues most relevant to Indigenous communities.” This year for the first time we take our content making skills into the community, hosting the ABC Digital Storytelling Workshop at the Garma Youth Forum. ABC content makers will teach young Australians how to tell the stories that matter to them and how they can have an impact on the world through storytelling, newsmaking and filmmaking. The workshop will be delivered by a team of Indigenous ABC content makers – Shahni Wellington (ABC Darwin), Molly Hunt (ABC Kimberley), Dan Bourchier (ABC Canberra) and Jack Evans (Behind the News presenter), with support from ABC Director of Entertainment and Specialist David Anderson, Indigenous Strategies Project Officer Tahnee Jash and BTN’s Emma Davis. -

— Get the Real Story with Tvnews

Informit TVNews — Get the real story with TVNews When the pursuit of truth is paramount, Informit TVNews is a vital educational resource for those seeking stories with integrity and diversity about the world around us. Search, stream and track the stories that matter to you from quality news and related current affairs stories broadcast by Australian free-to-air networks in this award-winning database. Collection highlights Key subjects Key titles – Access to a persistent archive of news content – Current Affairs – 60 Minutes dating back to 2007 – Documentary – ABC News – Includes unique, factual and authentic content only – News – A Current Affair – Essential resource for students, lecturers and – Current Events – Australian Story researchers – Media Studies – Behind The News – Track the stories that matter to you with our email – Personal Interest – Foreign Correspondent alert service Stories – Media Watch – Embed videos within your Learning Management – International Affairs – Q&A System – Insiders – Create clips of personalised selections, – Asia Pacific News pin favourites and share content – 7:30 – All copyright clearances covered under – Compass the Screenrights licence of your institution – Ad-free, always – No hardware or administration costs – New programs added daily Start searching now search.informit.org informit.org To request a free trial or quote, visit informit.org/trial-and-quote For more information, contact Informit | Email [email protected] | Call +61 39925 8210 — Get curated content delivered to you with -

The Gallipoli Story

Episode 10 Teacher Resource 28th April 2015 Anzac Centenary 1. Discuss the BtN Gallipoli story in pairs. Record the main Students will identify and discuss the historical origins of Anzac Day. Students will examine points of your discussion and share them with the class. the symbols and traditions associated with Anzac Day. 2. How many Australian soldiers fought at Gallipoli? 3. Describe the plan that Britain came up with to defeat Germany. 4. Which area did Britain want to take control of? 5. Where in Turkey were Australian and New Zealand soldiers History – Year 3 sent in? Days and weeks celebrated or commemorated in Australia (including Australia Day, ANZAC 6. The Gallipoli campaign became a stalemate. What does that Day, Harmony Week, National Reconciliation mean? Week, NAIDOC week and National Sorry Day) and the importance of symbols and emblems 7. What happened at the Battle of Lone Pine? (ACHHK063) 8. What was a `drip rifle’ and how did it help Australian soldiers? History – Years 4 - 7 9. How long did the Gallipoli campaign last? Sequence historical people and 10. What do you understand more clearly since watching the events (ACHHS081) (ACHHS098) (ACHHS117) (ACHHS205) Gallipoli story? Use historical terms (ACHHS082) (ACHHS099) (ACHHS118) (ACHHS206) History – Year 5 Identify and locate a range of relevant sources (ACHHS101) History – Years 5 & 6 Discussion Locate information related to inquiry questions in a range of sources Hold a classroom discussion recording (ACHHS102) (ACHHS121) students’ responses on the class white board. -

Digital Edition

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 1 JANUARY 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL THIRD TIME LUCKY? Political gridlock sends Israel back to the polls yet again THE EMPIRE BUILDER LEGAL HEIGHTS JEREMY AND THE UNRWA JEWS CONUNDRUMS Qassem Soleimani, the mastermind behind The Golan, international law and the Trump Ad- Why UK Labour’s The ins and outs of Iran’s regional adventurism .............. PAGE 19 ministration ......PAGE 30 leader strikes fear into Australia’s aid to the a long-established controversial UN community .....PAGE 25 body .............. PAGE 27 NAME OF SECTION WITH COMPLIMENTS AND BEST WISHES FROM GANDEL GROUP CHADSTONE SHOPPING CENTRE 1341 DANDENONG ROAD CHADSTONE VIC 3148 TEL: (03) 8564 1222 FAX: (03) 8564 1333 WITH COMPLIMENTS L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 2 AIR – January 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 1 REVIEW JANUARY 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR looks at how Israel ended up heading toward its third election in a year ON THE COVER Ton March 2 – and what might finally break the prolonged political stalemate in A woman votes at a polling Jerusalem. station in Rosh Haayin, Is- rael, Sept. 17, 2019. (Photo: We lead with veteran Israeli journalist Shmuel Rosner’s attempt to untangle the AAP/ Sebastian Scheiner) various complex circumstances that led to this impasse, while Ahron Shapiro explains the details of the different parties’ political demands and promises which meant a unity government could not be formed, as had been widely expected. In addition, Amotz Asa-El looks at the attempt to challenge current PM Binyamin Netanyahu’s leadership of the Likud party touched off by longtime rival Gideon Sa’ar. -

Full Australia Remembers Gallipoli Coverage Is Available Here

CONTENTS Introduction 3 ABC News 15 ABC Online 4 ABC + ABC News 24 16 ABC Television 5 ANZAC Day Coverage 17 ABC 6 Current Affairs Highlights 18 ABC2 8 ABC Radio 19 ABC3 9 Gallipoli The First Day: Centenary Edition App 21 ABC TV Education 11 Untold Stories From WWI Memorials 22 iview 14 A Century of Service 23 ABC Commercial 24 Programming Calendar 25-28 abc.net.au/anzac Every year, in presenting Anzac Day services and commemorations, yourself in significant events that have helped shape our national the ABC offers every Australian a way to connect and reflect upon identity. some of the most significant moments in the nation’s history. The day is an opportunity to think about the past, the present and the Over coming weeks you will find the very best of ABC programming— values that we share. This role is a matter of great pride and honour drama, documentary and discussion—across every ABC platform, for the ABC as the national broadcaster. television, radio and digital. This Anzac Day content is part of the ABC’s five year commitment to commemorating the centenary of In 2015, Anzac Day takes on greater significance as we mark the WWI. Centenary of Gallipoli. As always, the ABC will help Australians all over the country to participate in services and events which I want to thank both Senator the Hon. Michael Ronaldson, Minister recognise the contributions of the men and women who have for Veterans’ Affairs, the Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for served our nation. the Centenary of Anzac and the Special Minister of State and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, with whose assistance and great Anzac Day and the landings at Gallipoli offer a range of meanings. -

ABC NEWS Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABC NEWS Program Guide: National: Week 19 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 7 May 2017 .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Monday, 8 May 2017 ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Tuesday, 9 May 2017 .......................................................................................................................................... 14 Wednesday, 10 May 2017................................................................................................................................... 17 Thursday, 11 May 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 20 Friday, 12 May 2017 ............................................................................................................................................ 23 Saturday, 13 May 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 26 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 31 2 | P a g e ABC NEWS -

6 July 2018 5 Community News No Lanolin Which Makes It Hypoallergenic

6TH JULY 2018 – 20TH JULY 2018 VOL 35 – ISSUE 14 Sandstone MARK VINT Bathroom renovations MARK VINT starting from Sales open 7 days 9651 2182 $9,900 Buy Direct From the Quarry FAMILY OWNED & OPERATED 9651270 New Line2182 Road Prices Local Experienced 270Dural New NSW Line 2158 Road starting from tilers, vinyl installers 9652 1783 [email protected] NSW 2158 $59+gst/sq m to service the SOFA [email protected]: 84 451 806 754 for tiling Hills district. Gabion Spalls $16.50/T (min) STORE ABN: 84 451 806 754 1800 733 809 75mm - 150mm for baskets WWW.DURALAUTO.COM Visit us at unit 3A/827 Old Northern Road, Dural NSW 2158 WWW.DURALAUTO.COM www.duraltiles.com.au 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie MADE TO ORDER LOUNGE & SOFAS FRIENDSHIP, FELLOWSHIP AND FUN IN RETIREMENT What are you waiting for? Come and join PROBUS! WHAT IS PROBUS? Community News Community Probus provides you with the opportunity to meet with fellow retirees on a regular basis, listen to interesting speakers and join together in activities, all in the company of new friends. There are over 1,700 Probus Clubs with more than 125,000 Probus Club members all over Australia and New Zealand. You can join a mixed Probus Club or Clubs for Ladies or Men, the choice is yours. Membership is open to any member of the community who is retired or semi-retired and is looking for friendship, fellowship and fun. Great reasons to join PROBUS • Enjoy the fellowship of retirees in your community • Listen to interesting guest speakers • Attend monthly meetings in your local area • Participate