The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Above: These images appear in an article by Dr Patricia Clarke (see ANHG 93.4.10). Left: Jennie Scott Wilson, c.1888. Centre: Jennie Scott Wilson on her wedding day, 1897. Right: Jennie Scott Griffiths, Brisbane, 2 May 1920. [Papers of Jennie Scott Griffiths, nla.cat-vn1440105] Below: Miscellaneous Receipts, Tickets, Cards and Conference Badges, 1916–1920 [Papers of Jennie Scott Griffiths, nla.cat-vn1440105] AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 93 July 2017 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 September 2017. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 93.1.1 Fairfax Media: job cuts, strike and acquisition proposal Fairfax Media was in the headlines for three big reasons in the first week in May: (1) it announced it was going to cut one-quarter of its metropolitan journalistic staff; (2) its metropolitan journalists went out on strike for an “unprecedented” seven days; and (3) it received a proposal from a private equity firm interested in acquiring its metropolitan assets, principally Domain and its major mastheads, such as the Sydney Morning Herald, Age and Australian Financial Review. -

“Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4239–4257 1932–8036/20160005 Doing “Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News DEBING FENG1 Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China Unlike print news that is static and mainly composed of written text, television news is dynamic and needs to be delivered with diversified presentational modes and forms. Drawing upon Bakhtin’s heteroglossia and Goffman’s production format of talk, this article examined the presentational forms and strategies deployed in BBC News at Ten and CCTV’s News Simulcast. It showed that the employment of different presentational elements and forms in the two programs reflects two contrasting types of news discourse. The discourse of BBC News tends to present different, and even confrontational, voices with diversified presentational forms, such as direct mode of address and “fresh talk,” thus likely to accentuate the authenticity of the news. The other type of discourse (i.e., CCTV News) seems to prefer monologic news presentation and prioritize studio-based, scripted news reading, such as on-camera address or voice- overs, and it thus creates a single authoritative voice that is likely to undermine the truth of the news. Keywords: authenticity, mode of address, presentational elements, voice, television news The discourse of television news has been widely studied within the linguistic world. Early in the 1970s, researchers in the field of critical linguistics (CL; e.g., Fowler, 1991; Fowler, Hodge, Kress, & Trew, 1979; Hodge & Kress, 1993) paid great attention to the ideological meaning of news by drawing upon a kit of linguistic tools such as modality, transitivity, and transformation. -

Is the Government Listening? Now That the Uproar and Shouting About Alleged Bias Has Died Down, There Is Only One Issue Paramount for the ABC - Funding

Friends of the ABC (NSW) Inc. qu a rt e r ly news l e t t e r Se ptember 2005 Vol 15, No. 3 in c o rp o rat i n g ba ck g round briefing na tional magaz i n e up d a t e friends of the abc Is the Government listening? Now that the uproar and shouting about alleged bias has died down, there is only one issue paramount for the ABC - funding. The corporation has not been backward putting its case forward - notably the collapse of drama production to just 20 hours per annum. In the Melbourne Age, Director of ABC TV Sandra Levy referred to circumstances as "critical and tragic." around, low-cost end - we've pretty "We have all those important well done everything we can." obligations to indigenous programs, religious programs, science, arts, Costs up children’s programs ... things that the dramatically commercial networks don't, and yet Once the launch pad for great we probably battle along with about Australian drama, revelations that the a quarter of what they spend in a ABC's drama output has dwindled year - the disproportion is massive." from 100 hours four years ago to just Ms Levy's concerns have been 14 hours this year have received a lot echoed by managing director Russell of media attention. Balding and chairman Donald Ms Levy estimates that an hour McDonald, who have spent the past could cost anywhere from $500,000 few weeks publicly lamenting the to $2 million, 10 to 50 times more gravity of the funding crisis. -

Sound Bite Democracy

Sound Bite Democracy by Daniel C. Hallin tyranny of the sound stories and the role of the journalist in bite has been universally putting them together. Today,TV news is denounced as a leading much more "mediated"by journaliststhan cause of the low state of it was during the 1960s and early 70s. An- America's political dis- chors and reporterswho once played a rel- course. "Ifyou couldn't say atively passive role, frequently doing little it in less than 10 seconds," former gover- more than setting the scene for the candi- nor Michael Dukakis declared after the date or other newsmaker whose speech 1988 presidential campaign, "it wasn't would dominate the report, now more ac- heard because it wasn't aired." Somewhat tively "package"the news. This new style of chastened, the nation's television networks reporting is not so much a product of now are suggesting that they will be more journalistic hubris as the result of several generous in covering the 1992 campaign, converging forces- technological, politi- and some candidateshave alreadybeen al- cal, and economic- that have altered the lowed as much as a minute on the evening imperativesof TV news. news. However, a far more radical change To appreciatethe magnitude of this ex- would be needed to returneven to the kind traordinarychange, it helps to look at spe- of coverage that prevailed in 1968. cific examples. On October 8, 1968, Walter During the Nixon-Humphrey contest Cronkiteanchored a CBS story on the cam- that year, nearly one-quarterof all sound paigns of RichardNixon and Hubert Hum- bites were a minute or longer, and occa- phrey that had five sound bites averaging sionally a major political figure would 60 seconds. -

CMST 132 – Techniques & Technology of Propaganda Spring

CMST 132 – Techniques & Technology of Propaganda Spring 2019 INSTRUCTOR: Michael Korolenko PHONE: 425-564-4109 OFFICE HOURS: By Appointment TEXTBOOK: AMUSING OURSELVES TO DEATH, by Neil Postman COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course focuses on the technological and communicative techniques of film and video that allow information to be targeted at specific individuals and groups, to create opinions, generate sales, develop propaganda, and other goals of media persuasion. It is the goals to: 1) increase student awareness of media persuasion by examining a variety of historical and current media campaigns; 2) demonstrate the techniques and technologies of media-based persuasion; 3) give students the opportunity to test and validate persuasion techniques with simple media presentations; and 4) assist in the development of critical analysis skills as applied to the production of media messages. This will be accomplished through online "lectures", discussions, written assignments, and a variety of film and video clips. THE ONLINE COURSE will be presented in the form of a museum or World’s Fair exhibit dealing with the technology of persuasion and propaganda. Each area will contain different forms of propaganda: print, television, etc. as well as the types of propaganda and persuasion we face in our technological society: political, product-oriented, philosophically oriented, etc. COURSE LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of the class, the student will be able to: 1. define the terms: media, persuasion, propaganda, technology application, symbol, metaphor, "yellow journalism," editorial, sound bite, manipulation, soft sell, motivation, instructional training, education, hands-on, virtual reality, educational television, documentary film/video, docudrama, advertising, infomercial. 2. list and explain the significance of five or more historical examples of media persuasion and propaganda between 1600 and 1990. -

Society Persuasion In

PERSUASION IN SOCIETY HERBERT W. SIMONS with JOANNE MORREALE and BRUCE GRONBECK Table of Contents List of Artwork in Persuasion in Society xiv About the Author xvii Acknowledgments xix Preface xx Part 1: Understanding Persuasion 1. The Study of Persuasion 3 Defining Persuasion 5 Why Is Persuasion Important? 10 Studying Persuasion 14 The Behavioral Approach: Social-Scientific Research on the Communication-Persuasion Matrix 15 The Critical Studies Approach: Case Studies and “Genre-alizations” 17 Summary 20 Questions and Projects for Further Study 21 2. The Psychology of Persuasion: Basic Principles 25 Beliefs and Values as Building Blocks of Attitudes 27 Persuasion by Degrees: Adapting to Different Audiences 29 Schemas: Attitudes as Knowledge Structures 32 From Attitudes to Actions: The Role of Subjective Norms 34 Elaboration Likelihood Model: Two Routes to Persuasion 34 Persuasion as a Learning Process 36 Persuasion as Information Processing 37 Persuasion and Incentives 38 Persuasion by Association 39 Persuasion as Psychological Unbalancing and Rebalancing 40 Summary 41 Questions and Projects for Further Study 42 3. Persuasion Broadly Considered 47 Two Levels of Communication: Content and Relational 49 Impression Management 51 Deception About Persuasive Intent 51 Deceptive Deception 52 Expression Games 54 Persuasion in the Guise of Objectivity 55 Accounting Statements and Cost-Benefit Analyses 55 News Reporting 56 Scientific Reporting 57 History Textbooks 58 Reported Discoveries of Social Problems 59 How Multiple Messages Shape Ideologies 59 The Making of McWorld 63 Summary 66 Questions and Projects for Further Study 68 Part 2: The Coactive Approach 4. Coactive Persuasion 73 Using Receiver-Oriented Approaches 74 Being Situation Sensitive 76 Combining Similarity and Credibility 79 Building on Acceptable Premises 82 Appearing Reasonable and Providing Psychological Income 85 Using Communication Resources 86 Summary 88 Questions and Projects for Further Study 89 5. -

ABC TV 2015 Program Guide

2014 has been another fantastic year for ABC sci-fi drama WASTELANDER PANDA, and iview herself in a women’s refuge to shine a light TV on screen and we will continue to build on events such as the JONAH FROM TONGA on the otherwise hidden world of domestic this success in 2015. 48-hour binge, we’re planning a range of new violence in NO EXCUSES! digital-first commissions, iview exclusives and We want to cement the ABC as the home of iview events for 2015. We’ll welcome in 2015 with a four-hour Australian stories and national conversations. entertainment extravaganza to celebrate NEW That’s what sets us apart. And in an exciting next step for ABC iview YEAR’S EVE when we again join with the in 2015, for the first time users will have the City of Sydney to bring the world-renowned In 2015 our line-up of innovative and bold ability to buy and download current and past fireworks to audiences around the country. content showcasing the depth, diversity and series, as well programs from the vast ABC TV quality of programming will continue to deliver archive, without leaving the iview application. And throughout January, as the official what audiences have come to expect from us. free-to-air broadcaster for the AFC ASIAN We want to make the ABC the home of major CUP AUSTRALIA 2015 – Asia’s biggest The digital media revolution steps up a gear in TV events and national conversations. This year football competition, and the biggest football from the 2015 but ABC TV’s commitment to entertain, ABC’s MENTAL AS.. -

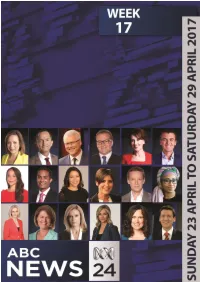

ABC News 24 Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABCNEWS24 Program Guide: National: Week 17 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 23 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 24 April 2017 .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 25 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Wednesday, 26 April 2017 .................................................................................................................................. 17 Thursday, 27 April 2017 ...................................................................................................................................... 20 Friday, 28 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................... 23 Saturday, 29 April 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 26 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 31 2 | P a -

Framing Malaysia in the News Coverage of Indonesian Television

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 7 No 2 S1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy March 2016 Framing Malaysia in the News Coverage of Indonesian Television Hamedi M. Adnan Amri Dunan Department of Media Studies, Faculty of Art and Social Sciences of Malaya University, 50603 Kuala Lumpur [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n2s1p45 Abstract During the administration period of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), Indonesia-Malaysia relationship became worse due to certain issues. There are three important issues affected relationship between Indonesia-Malaysia—political issue (Ambalat issue), economic issue (Indonesian migrant worker-TKI) and cultural issue (Pendet dance). The question rise up in Indonesia- Malaysia relationship caused by the response and the sensitively from Indonesian which affected by the media framing, included media television. This research is to identify how framing is created and identify the media television framing. This research uses framing analysis of ‘Television News’ model developed from Gamson & Mogdiliani (1989) model and uses the inductive qualitative analysis process developed from the model of Van Gorp (2005/2010). The model refers to the identification method in verbal framing or nonverbal framing with the matrix method. In-depth interviews were conducted to 12 peoples— each four from television stations Metro TV, TV One and TVRI. Each of them consists of a reporter, cameraman, producer and redaction leader. This in-depth interview proposed to know ‘how’ and ‘why’ the verbal and nonverbal framing is done by the stations. Triangulation between framing analysis of ‘television news’ model, in-depth interview and the observation shows that the basic ideology such as nationalism from the media owner affect the media framing on Malaysia. -

ABC Special Coverage As Garma Festival Turns 20

Media Release: 25 July 2018 ABC special coverage as Garma Festival turns 20 In a special year for the Garma Festival – its 20th anniversary – the ABC is proud to again participate in this iconic event as Official Media Partner, as well as presenting a special programming slate to Australians nationally. The ABC will also assist NITV with its coverage. 2018 Garma will be held from 3-6 August at Gulkula in North-East Arnhem Land. This year’s theme is Yuwalk Lakaraŋa – or truth-telling. ABC Managing Director Michelle Guthrie said: “Garma takes pride of place on the ABC’s national calendar of events. The annual festival is a major celebration of Indigenous culture and conversations and the ABC is proud to play a role in ensuring its success. “The ABC broadcasts live from one of most culturally significant gatherings in Australia so that the message of Garma – this year Yuwalk Lakaraŋa – travels far beyond the sacred Yolngu site. “We have renewed our commitment to Garma this year not only because it brings Indigenous Australians together to talk frankly with each other, but because it helps focus attention on the issues most relevant to Indigenous communities.” This year for the first time we take our content making skills into the community, hosting the ABC Digital Storytelling Workshop at the Garma Youth Forum. ABC content makers will teach young Australians how to tell the stories that matter to them and how they can have an impact on the world through storytelling, newsmaking and filmmaking. The workshop will be delivered by a team of Indigenous ABC content makers – Shahni Wellington (ABC Darwin), Molly Hunt (ABC Kimberley), Dan Bourchier (ABC Canberra) and Jack Evans (Behind the News presenter), with support from ABC Director of Entertainment and Specialist David Anderson, Indigenous Strategies Project Officer Tahnee Jash and BTN’s Emma Davis. -

Where the Red Line Is Drawn Was Perceived by Many to Be Self-Evident and Universal, but Interestingly Enough Perceived Differently in Kampala and Gulu

Political Science, Advanced Course C Department of Government Bachelor Thesis Autumn 2016 Where the R ed Line is Drawn A study on Self- censorship in Ugandan Media Author: Joanna Hellström Supervisor: Johanna Söderström Pages: 49 Words: 13 945 Abstract Coercion and repressive legislation are widely recognised measures employed by hybrid regimes as a way of stifling the media. This thesis illustrates the long shadow cast by these measures by examining the impact of transgressions on self-censorship among Ugandan journalists, and how these are weighed against their notion of professionalism. Self- censorship is experienced as an unwanted, but vital practice that moves in tandem with the level of political tension, being an extraordinary rather than general measure. The study was conducted in the summer of 2016, founded by a Minor Field Study scholarship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). List of Abbreviations AMB African Media Barometer CBS Central Broadcasting Service HRNJ-U Human Rights Network for Journalists- Uganda HRW Human Rights Watch ICT Information and Communications Technology RDC Resident District Commissioner RSF Reporters Without Borders UCC Uganda Communications Commission 2 Acknowledgements I would like to start by expressing my deepest appreciation to my supervisor Johanna Söderström for her guidance and unyielding belief in my capability. Furthermore, I am heavily indebted to the Uganda Radio Network, who warmly welcomed me and went out of their way to contribute to my work with their knowledge; Sam Gummah, Sylvia Nsubuga Nankya, Douglas Mutumba, Alex Otto, Olive Eyotaru, Leonard Namukasa and Isaac Mugera. I give my warmest regards to Moses Odokonyero at Northern Uganda Media Club, Grace Nataabalo at the African Centre for Media Excellence, Kenneth Ntende and Robert Ssempala at Human Rights Network for Journalists, for providing me with an invaluable contextual background. -

Communications Campaign Best Practices

Communications Campaign Best Practices Authors Contributing Editors © January 2008, Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) and the Movement Advancement Project (MAP). All rights reserved. Communications Campaign 1 Best Practices Communications Campaign Best Practices Introduction 3 Effective Communications Campaigns 3 Elements of an Effective Communications Campaign 3 Setting a Campaign Objective 3 Three Things to Consider When Setting Campaign Objectives 3 Target Audience 7 This Campaign Isn’t About You 7 The General Public Isn’t a Target Audience 7 Five Ways to Narrow Your Target Audience 7 Messaging and Creative Development 9 If You Can’t Test It, Don’t Run It 9 Messaging and Creative Should Be Based on Research 9 Six Steps to Effective Messaging and Creative 9 Stay on Message! 11 Market Research Overview 13 Why You Should Understand Market Research 13 Hiring a Good Market Research or Political Polling Firm 13 Market Research Basics 14 Qualitative Market Research 17 In-Depth Interviews 17 Focus Groups 17 Five Deadly Focus Group Mistakes 18 Elicitation Techniques 19 A Note about Online Research 19 Limitations of Qualitative Research 19 Quantitative Market Research 21 Sample Selection 21 Survey Design 22 Question Sequencing 23 Question Scales 24 Clear, Unbiased Questions 24 Split Samples 25 Interpreting Results 25 Survey Types 26 Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Research 26 Creative Testing 29 2 Basic Creative Testing 29 What to Test 30 Limitations 30 Media Planning 31 Creating a Media Plan 31 Buying Media 32 Post-Buy