Dispensational Modernism by Brendan Pietsch Graduate Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameron Townsend: Good News in Every Language Free

FREE CAMERON TOWNSEND: GOOD NEWS IN EVERY LANGUAGE PDF Janet Benge,Geoff Benge | 232 pages | 05 Dec 2001 | YWAM Publishing,U.S. | 9781576581643 | English | Washington, United States William Cameron Townsend - Only One Hope He graduated from a Presbyterian school and attended Occidental College in Los Angeles for a time but did not graduate. He joined the National Guard inpreparing to go to war for his country. Before he had any assignments from the military, he spent some time with Stella Zimmerman, a missionary who was on furlough. You are needed in Central America! Cameron Townsend was unhappy about being called a coward and chose to pursue the missions call instead. He requested to be released from soldier service and to be allowed to become a Cameron Townsend: Good News in Every Language overseas instead. Over the next year he traveled through Latin America. During this time, he met another missionary who felt called to Latin America named Elvira. The two married in July He spread the Gospel in Spanish but felt that this was not accessible to the indigenous people of the country. For this reason, he went to Santa Catarina and settled in a Cakchiquel community where he learned the native language. He spent fourteen years there, learning and then translating the Bible into the local language. He started a school and medical clinic, and set up a generator of electricity, a plant to process coffee, and a supply store for agriculture. Townsend felt that the standard missionary practices neglected some of the needs of the people, as well as ignoring the cultures and languages of many of the groups. -

The Glory of God and Dispensationalism: Revisiting the Sine Qua Non of Dispensationalism

The Journal of Ministry & Theology 26 The Glory of God and Dispensationalism: Revisiting the Sine Qua Non of Dispensationalism Douglas Brown n 1965 Charles Ryrie published Dispensationalism Today. In this influential volume, Ryrie attempted to explain, I systematize, and defend the dispensational approach to the Scriptures. His most notable contribution was arguably the three sine qua non of dispensationalism. First, a dispensationalist consistently keeps Israel and the church distinct. Second, a dispensationalist consistently employs a literal system of hermeneutics (i.e., what Ryrie calls “normal” or “plain” interpretation). Third, a dispensationalist believes that the underlying purpose of the world is the glory of God.2 The acceptance of Ryrie’s sine qua non of dispensationalism has varied within dispensational circles. In general, traditional dispensationalists have accepted the sine qua non and used them as a starting point to explain the essence of dispensationalism.3 In contrast, progressive dispensationalists have largely rejected Ryrie’s proposal and have explored new ways to explain the essential tenants of Douglas Brown, Ph.D., is Academic Dean and Senior Professor of New Testament at Faith Baptist Theological Seminary in Ankeny, Iowa. Douglas can be reached at [email protected]. 2 C. C. Ryrie, Dispensationalism Today (Chicago: Moody, 1965), 43- 47. 3 See, for example, R. Showers, There Really Is a Difference, 12th ed. (Bellmawr, NJ: Friends of Israel Gospel Ministry, 2010), 52, 53; R. McCune, A Systematic Theology of Biblical Christianity, vol. 1 (Allen Park, MI: Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary, 2009), 112-15; C. Cone, ed., Dispensationalism Tomorrow and Beyond: A Theological Collection in Honor of Charles C. -

2015-2016 National Scar Committee Standing Scien

MEMBER COUNTRY: USA NATIONAL REPORT TO SCAR FOR YEAR: 2015-2016 Activity Contact Name Address Email Web Site NATIONAL SCAR COMMITTEE Senior Program Officer, Staff to Delegation U.S. Polar Research Board The National National Academy of Academies Polar Laurie Geller [email protected] http://dels.nas.edu/prb/ Sciences Research Board 500 Fifth Street NW (K-649) Washington DC 20001 SCAR DELEGATES School of Earth Sciences Ohio State University 1 Delegate/ President, Terry Wilson 275 Mendenhall Lab [email protected] Executive Committee 125 S Oval Mall Columbus, OH 43210 Departments of Biology and Environmental Science HR 347 2 Alternate Delegate Deneb Karentz University of San Francisco [email protected] 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117- 1080 STANDING SCIENTIFIC GROUPS GEOSCIENCES Director Byrd Polar Research 1 Chief Officer of Laboratory W Berry Lyons [email protected] Geosciences SSG The Ohio State University 1090 Carmack Road Columbus, OH 43210-1002 1 Activity Contact Name Address Email Web Site Associate Professor of Geological Sciences University of Alabama 2 Samantha Hansen [email protected] 2031 Bevill Bldg. Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 Department of Geosciences Earth and Environmental Systems Institute Prof Sridhar 3 Pennsylvania State [email protected] Anandakrishnan University 442 Deike Building University Park, PA 16802 PHYSICAL SCIENCES Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences 1 Dr John Cassano University of Colorado at [email protected] Boulder 216 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 The Glaciers Group 4th Floor -

Opening God's Word to the World

AMERICAN BIBLE SOCIETY | 2013 ANNUAL REPORT STEWARDSHIP God’S WORD GOES FORTH p.11 HEALING TRAUMA’S WOUNDS p.16 THE CHURCh’S ONE FOUNDATION p.22 OPENING GOd’s WORD TO THE WORLD A New Chapter in God’s Story CONTENTS Dear Friends, Now it is our turn. As I reflect on the past year at American Bible Society, I am Nearly, 2,000 years later, we are charged with continuing this 4 PROVIDE consistently reminded of one thing: the urgency of the task before important work of opening hands, hearts and minds to God’s God’s Word for Millions Still Waiting us. Millions of people are waiting to hear God speak to them Word. I couldn’t be more excited to undertake this endeavor with through his Word. It is our responsibility—together with you, our our new president, Roy Peterson, and his wife, Rita. 6 Extending Worldwide Reach partners—to be faithful to this call to open hands, hearts and Roy brings a wealth of experience and a passionate heart for 11 God’s Word Goes Forth minds to the Bible’s message of salvation. Bible ministry from his years as president and CEO of The Seed This task reminds me of a story near the end of the Gospel Company since 2003 and Wycliffe USA from 1997-2003. He of Luke. Jesus has returned to be with his disciples after the has served on the front lines of Bible translation in Ecuador and resurrection. While he is eating fish and talking with his disciples, Guatemala with Wycliffe’s partner he “opened their minds to understand the Scriptures.” Luke 24.45 organization SIL. -

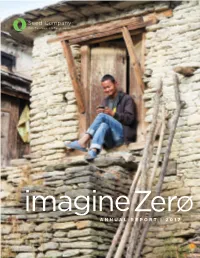

ANNUAL REPORT | 2017 | ANNUAL REPORT Imagine Imagine

Ø Zer ANNUAL REPORT | 2017 | ANNUAL REPORT imagine SEED COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT | 2017 GREETINGS IN JESUS’ NAME SAMUEL E. CHIANG | President and CEO 2 3 _ _ We praise God for Fiscal Year 2017. With the unaudited numbers in, I’m humbled and happy to report that FY17 contribution income totaled $35.5 million — a $1.1 million increase over FY16, God provided. God increased our ministry reach. God paved the way for truly despite the immense loss of the illumiNations 2016 gathering. unprecedented partnership. And God steered us through difficulty where there seemed to be no good way through. A New Day in Nigeria During all of FY17, we watched God shepherd Seed Company through innovation, In the first and second quarter of FY17, a series of unfortunate events led Seed Company to dissolve its partnership with a long-term partner in Africa. However, acceleration and generosity. We invite you to celebrate with us and focus upon God. from a grievous and very trying situation, God brought redemption that only He could provide. FROM THE PRESIDENT When the dissolution of the partnership was completed, we naturally assumed Seed Company continues our relentless pursuit of Vision 2025. I am reminded we would have to curb our involvement in Africa’s most populous nation, home that the founding board prayerfully and intentionally recorded the very first to more than 500 living languages. God had other plans. board policy: The board directs management to operate Seed Company in an The Lord surprised us. We watched the Lord stir new things into motion for the outcomes-oriented manner. -

Is God an American?

IS GOO AN AMERICAN? An Anthropological Perspective on the Missionary Work of the Summer Institute of Linguistics Edited by S11ren Hvalkof and Peter Aaby IWGINSI IS GOD AN AMERICAN? This is a joint publication by the following two organizations: INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS (IWGIA) Fiolstrrede I 0, DK- 1171 Copenhagen K, Denmark. SURVIVAL INTERNATIONAL 36 Craven Street, London WC2N 5NG, England. Copyright 1981 by S~ren Hvalkof, Peter Aaby, IWGIA and Survival International. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be. reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means without permission of the editors. ISSN 0105-4503 ISBN 87-980717-2-6 First published 1981 by IWGIA and Survival International. Printed in Denmark by Vinderup Bogtrykkeri A/S. Front cover by H. C. Poulsen. IS GOD AN AMERICAN? An Anthropological Perspective on the Missionary Work ofthe Summer Institute ofLinguistics EDITED BY &tren Hvalkof and Peter Aaby INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Objectives IWGIA is a politically independent, international organization concerned with the oppression of indigenous peoples in many countries. IWGIA's objective is to secture the future of the indigenous peoples in concurrence with their own efforts and desires: 1. By examining their situation, and publishing information about it. 2. By furthering international understanding, knowledge and involvement in the indigenous peoples' situation. 3. By fighting racism and securing political, economic and social right, as well as establishing the indigenous peoples' right to self-determination. 4. By arranging humanitarian projects and other forms of support of in digenous peoples and ethnic groups with a view of strengthening their social, cultural and political situation. -

American Baptist Foreign Mission

American Baptist Foreign Mission ONE-HUNDRED-NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT Presented by the Board o f Managers at the Annual Meeting held in W ashington, D. C., M ay 23-28, 1933 Foreign Mission Headquarters 152- Madison Avenue New York PRINTED BY RUMFORD PRESS CONCORD. N. H. U .S . A - CONTENTS PAGE OFFICERS ................................................................................................................................... 5 GENERAL AGENT, STATE PROMOTION DIRECTORS .................... 6 BY-LAWS ..................................................................................................................................... 7 -9 PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 11 GENERAL REVIEW OF THE YEAR .................................................................1 5 -5 7 T h e W o r l d S it u a t i o n ................................................................................................ 15 A r m e d C o n f l ic t in t h e F a r E a s t ..................................................................... 16 C iv i l W a r in W e s t C h i n a ...................................................................................... 17 P h il ip p in e I ndependence ....................................................................................... 17 I n d ia ’ s P o l it ic a l P r o g r a m ..................................................................................... 18 B u r m a a n d S e p a r a t i o n ............................................................................................. 18 R ig h t s o f P r o t e s t a n t M is s io n s in B e l g ia n C o n g o ............................... 19 T h e W o r l d D e p r e s s io n a n d M i s s i o n s ........................................................... 21 A P e n t e c o s t A m o n g t h e P w o K a r e n s ........................................................... -

Xviith CENTURY

1596. — Bear Island (Beeren Eylandt — Björnöja) is discovered by Barentz who killed a white bear there. Visited in 1603 by Stephen Bennett who called it Cherk IsL after his employer Sir F. Cherie, of the Russian Company. Scoresby visited it in 1822. It was surveyed in 1898 by A. G. Nathorst’s Swedish Arctic expedition. N 1596. — On June 17, W. Barentz and the Dutch, expedition in search of a N.-E. passage, sights West Spitzbergen. He called Groeten Inwick what is now Ice fjord (Hudson’s Great indraught in 1607) a name which was given to it by Poole in 1610. Barentz thought that Spitzbergen was part of Greenland. Barentz also discovered Prince Charles Foreland which he took to be an island and which was called Black point Isle by Poole in 1610. It was in 1612 that English Whalers named it after Prince Charles, son of James VI of Scotland, who became Charles I later. In 1607-1610, following the reports made by Hudson, of the Muscovy Company, a whaling industry was established in Spitzbergen. The scientific exploration of Spitz bergen has been going on ever since 1773, which was the year of Captain Phipps’s British expedition in which Horatio Nelson, took part. Explored by Sir Martin 丨Cònway.in 1896. By the Prince of Monaco and Doctor W. S. Bruce in 1906. By the Scottish Spitzbergen Syndicate of Edinburgh in 1920 and by the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. 1598. ~• The Dutch admiral Jacob Cornel is van Necq, commanding the “ Mauritius” takes possession of Mauritius and pursues his voyage of Dutch colonisation to the Moluccas (Amboina) then to Te mate in 1601 with the “ Amsterdam ” and “ Utrecht ”,whilst the Hispano-Portuguese had settled at Tidor. -

Amillennialism Reconsidered Beatrices

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1,185-210. Copyright 0 2005 Andrews University Press. AMILLENNIALISM RECONSIDERED BEATRICES. NEALL Union College Lincoln, Nebraska Introduction G. K. Beale's latest commentary on Revelation and Kim Riddlebarger's new book A Casefor Ami~~ennialismhave renewed interest in the debate on the nature of the millennium.' Amillennialism has an illustrious history of support from Augustine, theologians of the Calvinistic and ~utheran confessions, and a long line of Reformed theologians such as Abraham Kuyper, Amin Vos, H. Ridderbos, A. A. Hoekema, and M. G. line? Amillennialists recognize that a straightforward reading of the text seems to show "the chronologicalp'ogression of Rev 19-20, the futurity of Satan's imprisonment,the physicality of 'the first resurrection' and the literalness of the one thousand years" (emphasis supplied).) However, they do not accept a chronologicalprogression of the events in these chapters, preferring instead to understand the events as recapitulatory. Their rejection of the natural reading of the text is driven by a hermeneutic of strong inaugurated eschatology4-the paradox that in the Apocalypse divine victory over the dragon and the reign of Christ and his church over this present evil world consist in participating with Christ in his sufferings and death? Inaugurated eschatology emphasizes Jesus' victory over the powers of evil at the cross. Since that monumental event, described so dramatically in Rev 12, Satan has been bound and the saints have been reigning (Rev 20). From the strong connection between the two chapters (see Table 1 below) they infer that Rev 20 recapitulates Rev 12. -

Founding Friends 12 from Pacific to George Fox 14 a Time for Growth 20

The magazine of George Fox University | Winter 2016 Founding Friends 12 From Pacific to George Fox 14 A Time for Growth 20 EDITOR Jeremy Lloyd ART DIRECTOR Darryl Brown COPY EDITOR Sean Patterson PHOTOGRAPHER Joel Bock CONTRIBUTORS Ralph Beebe Melissa Binder Kimberly Felton Tashawna Gordon Barry Hubbell Richard McNeal Arthur Roberts Brett Tallman George Fox Journal is published two times a year by George Fox University, 414 N. Meridian St., Newberg, OR, 97132. Postmaster: Send address changes to Journal, George Fox University, 414 N. Meridian St. #6069, Newberg, OR 97132. PRESIDENT Robin Baker EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, ENROLLMENT AND MARKETING Robert Westervelt DIRECTOR OF MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS Rob Felton This issue of the George Fox Journal is printed on 30 per- cent post-consumer recycled paper that is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council to be from well-managed forests and recycled wood and fiber. Follow us: georgefox.edu/social-media George Fox Journal Winter 2016 Book Review: My Calling to Ministry 17 4 Bruin Notes The Harmony Tree 8 By Tashawna Gordon 28 Annual Report to Donors OUR VISION By Richard McNeal 36 Alumni Connections To be the Christian Minthorn Hall Then and Now 18 university of choice CELEBRATING 125 YEARS 10 A New Era: Record 50 Donor Spotlight known for empowering students to achieve It All Began in 1891 12 Enrollment 20 exceptional life outcomes. By Ralph Beebe By Melissa Binder OUR VALUES From Pacific to George Fox 14 Blueprint for Success: By Arthur Roberts p Students First Music and Engineering 24 p Christ in Everything It’s About the People 15 By Brett Tallman p Innovation to Improve Outcomes By Peggy Fowler Into the Fire: Blazing a Path Before Be Known 16 for Female Firefighters 26 By Kimberly Felton COVER PHOTO By Barry Hubbell From the archives: Wood-Mar Hall under construction in 1911. -

Millennialism, Rapture and “Left Behind” Literature. Analysing a Major Cultural Phenomenon in Recent Times

start page: 163 Stellenbosch Theological Journal 2019, Vol 5, No 1, 163–190 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2019.v5n1.a09 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2019 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Millennialism, rapture and “Left Behind” literature. Analysing a major cultural phenomenon in recent times De Villers, Pieter GR University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article represents a research overview of the nature, historical roots, social contexts and growth of millennialism as a remarkable religious and cultural phenomenon in modern times. It firstly investigates the notions of eschatology, millennialism and rapture that characterize millennialism. It then analyses how and why millennialism that seems to have been a marginal phenomenon, became prominent in the United States through the evangelistic activities of Darby, initially an unknown pastor of a minuscule faith community from England and later a household name in the global religious discourse. It analyses how millennialism grew to play a key role in the religious, social and political discourse of the twentieth century. It finally analyses how Darby’s ideas are illuminated when they are placed within the context of modern England in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century. In a conclusion some key challenges of the place and role of millennialism as a movement that reasserts itself continuously, are spelled out in the light of this history. Keywords Eschatology; millennialism; chiliasm; rapture; dispensationalism; J.N. Darby; Joseph Mede; Johann Heinrich Alsted; “Left Behind” literature. 1. Eschatology and millennialism Christianity is essentially an eschatological movement that proclaims the fulfilment of the divine promises in Hebrew Scriptures in the earthly ministry of Christ, but it also harbours the expectation of an ultimate fulfilment of Christ’s second coming with the new world of God that will replace the existing evil dispensation. -

4.1 Eschatological Chronology

The Need for Teaching the Eschatological Gospel of Both Comings of Jesus Christ in the 21st Century . 4.1 ESCHATOLOGICAL CHRONOLOGY Part 1 laid out the biblical and theological foundation for this study of the Eschatological Gospel of Both Comings of the Lord Jesus Christ by defining pertinent terms and concepts. Then both the Old and New Testaments’ usage of the Eschatological Gospel and related concepts was addressed (e.g., kingdom of God/heaven, age or world to come, salvation history, kairos versus chronos time, Parousia/Second Coming of Jesus, etc.). This was done in light of the Parable of the Wheat and Tares/Weeds showing that both the kingdom of God (based on the orthodox Eschatological Gospel) and the kingdom of Satan (based on the heretical/“false” gospel) were to coexist on the earth until “the end of the age.” Part 2 then reviewed the historical foundation of the Eschatological Gospel throughout the Church Age. The firm and sure foundation laid by Jesus and His Apostles was the starting point, which was immediately followed by the Early Church Fathers, and then stretched well into the eighth century. There remained a small stream of Eschatological Gospel teaching spanning the rest of the Medieval Church Period, that led up to the Pre-Reformation Period and the beginning of the resurgence of the doctrine. This then continued to build through the Reformation and Post-Reformation periods well into the eighteenth century and culminated with the “birth” of Dispensationalism through Edward Irving and John Nelson Darby in the 1830s. This exploded throughout the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century; which in turn led to the founding of several churches, evangelical ministries and even one seminary upon the Eschatological Gospel (e.g., Plymouth Brethren, Christian and Missionary Alliance, Assemblies of God, Dispensational Baptists, Church of the International Foursquare Gospel, Billy Graham’s and Oral Roberts’ ministries, and Dallas Theological Seminary).