Peter Snell Institute of Sport: Managing Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tricks of the Trade for Middle Distance, Distance & XC Running

//ÀVÃÊvÊÌ iÊ/À>`iÊvÀÊÀVÃÊvÊÌ iÊ/À>`iÊvÀÊ ``iÊ ÃÌ>Vi]ÊÊ``iÊ ÃÌ>Vi]ÊÊ ÃÌ>ViÊ>`ÊÊ ÃÌ>ViÊ>`ÊÊ ÀÃÃ ÕÌÀÞÊ,Õ} ÀÃÃ ÕÌÀÞÊ,Õ} Ê iVÌÊvÊÌ iÊÊ iÃÌÊ,Õ}ÊÀÌViÃÊvÀÊÊ * ÞÃV>Ê `ÕV>ÌÊ }iÃÌÊ>}>âi ÞÊ VÊÃÃ How to Navigate Within this EBook While the different versions of Acrobat Reader do vary slightly, the basic tools are as follows:. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Make Page Print Back to Previous Actual Fit in Fit to Width Larger Page Page View Enlarge Size Page Window of Screen Reduce Drag to the left or right to increase width of pane. TOP OF PAGE Step 1: Click on “Bookmarks” Tab. This pane Click on any title in the Table of will open. Click any article to go directly to that Contents to go to that page. page. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Double click then enter a number to go to that page. Advance 1 Page Go Back 1 Page BOTTOM OF PAGE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Tricks of the Trade for MD, Distance & Cross-Country Tricks of the Trade for Middle Distance, Distance & Cross-Country Running By Dick Moss (All articles are written by the author, except where indicated) Copyright 2004. Published by Physical Education Digest. All rights reserved. ISBN#: 9735528-0-8 Published by Physical Education Digest. Head Office: PO Box 1385, Station B., Sudbury, Ontario, P3E 5K4, Canada Tel/Fax: 705-523-3331 Email: [email protected] www.pedigest.com U.S. Mailing Address Page 3 Box 128, Three Lakes, Wisconsin, 54562, USA ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Tricks of the Trade for MD, Distance & Cross-Country This book is dedicated to Bob Moss, Father, friend and founding partner. -

© 21St Century Math Projects

© 21st Century Math Projects Project Title: Mile Run Standard Focus: Data Analysis, Patterns, Algebra & Time Range: 3-4 Days Functions Supplies: TI Graphing Technology Topics of Focus: - Scatterplots - Creating and Applying Regression Functions - Interpolation & Extrapolation of Data Benchmarks: 4. For a function that models a relationship between two quantities, interpret key Interpreting F-IF features of graphs and tables in terms of the quantities, and sketch graphs showing key Functions features given a verbal description of the relationship. 6. Calculate and interpret the average rate of change of a function (presented Interpreting F-IF symbolically or as a table) over a specified interval. Estimate the rate of change from a Functions graph.★ Building Functions F-BF 1. Write a function that describes a relationship between two quantities.★ Interpreting 6a. Fit a function to the data; use functions fitted to data to solve problems in the Categorical and S-ID context of the data. Use given functions or choose a function suggested by the context. Quantitative Data Emphasize linear and exponential models. Interpreting Categorical and S-ID 6c. Fit a linear function for a scatter plot that suggests a linear association. Quantitative Data Procedures: A.) Students will use Graphing Calculator Technology to make scatterplots using data from the “Mile Run Chart”. (Graphing Calculator Instructions insert included) B.) Students will complete the three parts of the Mile Run Project. © 21st Century Math Projects The Mile Run In 1593, the English Parliament declared that 5,280 feet would equal 1 mile. Ever since, a mile run has become a staple fitness test everywhere -- from militaries to the high school gyms. -

Marathon Championship

CLUB KIWIFRUIT FUND RAISING PICK As reported in Ramblings newsletter, 6th June, 1992. The annual Shallcross kiwifruit pick was once again offered to Tauranga Ramblers to give our funds a much needed boost so that we can subsidise club days, Bar-B-Q’s, Pinto, buses, newsletters and travel to major events. All in all club members receive more than their subscriptions cover, therefore we need full support from all participants for our fund-raising efforts. The club is very appreciative of the chances to earn this money and a special thanks go to Bill and Marge Shallcross for this fruit picking opportunity. It certainly beats selling raffle tickets and gives us the chance to do something other than one’s usual job or studies. It is quite an education especially the way different people see the hairy berries – their shapes and sizes I’ll leave to your imagination. Colin Clifton commented that it was a change from working alone. Teresa Coston was certainly the noisiest and Kristin McLoughlin one of the quietest, but it was good to see everyone turn out. Some brought their spouses, or sons and daughters. Robyn Bint did a great job removing all the kiwifruit stalks. Marge did a great job of keeping the team fed, while Nigel Hines had done an absolutely fantastic job chasing along all members he could find. Over the two days we picked 162 bins compared to 166 last year. Unfortunately we couldn’t quite finish but Ramblers received $1400.00 for the two day’s work. Once again special thanks to Bill, Marge, Debbie, Russell, Rob Shallcross and his in-laws and to Nigel and Sheryl Hines for their organisation. -

Vetrunner June 2008.Pub

VETRUNNER Email: [email protected] ISSN 1449-8006 Vol. 29 Issue 10 — June 2008 MAJURA — cool & crisp but a warm inner glow at the finish (Handicap report for 27th April 2008 by Geoff Barker) home in 19th position to claim the bronze medal. Emma found it rewarding to receive a medal especially after her Even though the balloons could not fly, the ACT Vets increased new handicap, and hopes it is an indication that (Masters?) flew around the Majura course like there was no her fitness level is improving each month. It was the most tomorrow. It was a cool, crisp morning with a bit of a chill challenging run Emma has attempted in her three months wind reminding us all that winter is here. Everyone also of running. She found the start the most difficult and warmed to see Marco Falzarano – albeit briefly do a bit of a thought the last bit before the turn ‘cruel’. However she jog/walk up the first 100 metres. And the absence of Alan enjoyed the end. She now feels competitive with Anthony, Duus, Jane Bell, Ros Pilkinton and John Littler has been Mike and Robyn and hopes it will not be too long before she noted! overtakes them all in the family medal tally. Daughter Mollie, who uses the childcare facilities, is not included. FRYLINK series Heather Koch, who was first over the line in April, First over the line was Carol Bennett, who became came home in 25th position. another of these women who simply ran off into the pale Tony Harrison, one of the most important people at blue cold day, and has not been seen since. -

Athlete-Training-Schedule-Template

Arthur Lydiard’s Athletic Training Training Summary for Middle Distance and Distance Running based on the Lydiard Principles Edited and footnotes added by Nobby Hashizume TABLE OF CONTENTS 1) Arthur Lydiard – A Brief Biography 2) Introduction to the Lydiard System 3) Marathon Conditioining 4) Hill Resistance 5) Track Training 6) How to Set-out a Training Schedule 7) Training Considerations 8) The Schedule 9) Race Week/Non-Race Week Schedules 10) Running a Marathon 11) When You Run a Marathon, Be Sure That You… 12) How to Lace Your Shoes 13) Nutritions and More 14) Training Terms 15) Glossary 16) Training Schedule for 10km (sample) 17) Training Schedule (Your Own) 18) Lecture Notes 1 ARTHUR LYDIARD – A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY Arthur Lydiard was born by Eden Park, New Zealand, in 1917. In school, he ran and boxed, but was most interested in rugby football. Because of the Great Depression of the 1920’s, Lydiard dropped out of school at 16 to work in a shoe factoryc. Lydiard figured he was pretty fit until Jack Dolan, president of the Lynndale Athletic Club in Auckland and an old man compared to Lydiard, took him on a five-mile training jog. Lydiard was completely exhausted and was forced to rethink his concept of fitness. He wondered what he would feel like at 47, if at 27 he was exhausted by a five-mile run. Lydiard began training according to the methods of the time, but this only confused him further. At the club library he found a book by F.W. Webster called “The Science of Athletics.” But Lydiard soon decided that the schedules offered by Webster were being too easy on him, so he began experimenting to find out how fit he could get. -

Nick Willis Discipline: Middle Distance Running Specialist Events: 800M and 1500M

CHAT with a Olympic Education CHAMPION Nick Willis Discipline: Middle distance running Specialist events: 800m and 1500m Nick Willis was born in Lower Hutt (near Wellington) in 1983.Running talent obviously runs in the Willis family, as Nick and his brother Steve are the only brothers in the history of New Zealand to run a mile in less than 4 minutes. When he was at Hutt Valley High School in January 2001, Nick became the fastest New Zealand student to run a mile in just 4 minutes and 1.33 seconds. After high school, Nick was awarded an athletics scholarship at the University of Michigan in the United States of America. He thrived in the environment, and his running went from strength to strength. He represented New Zealand at the 2004 Athens Olympic Games and the 2005 World Championships, reaching the semi- final each time. At the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games, Nick took the Gold Medal in the 1500m. In 2008, he reached the final of the 1500m at the Beijing Olympic Games. After a tight race, Nick finished third to claim the Bronze Medal. In 2009, the winner of the race, Rashid Ramzi, was disqualified because of a positive drug test. So Nick’s Bronze Medal was upgraded to a Silver. (For further information on Nick’s experiences at the 2008 Olympic Games, see “It Pays to Play Fair” in the Living the Olympic Values resource, http:// www.olympic.org.nz/education/living-olympic-values) At the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi, Nick was recovering from knee surgery, but he didn’t let this stop him from winning the Bronze Medal. -

Rich Englehart Interviews Peter Snell (Snell Talks About the Running He's

Rich Englehart Interviews Peter Snell (Snell talks about the running he’s doing now – he does 3 miles of walking and jogging with his wife, and some cycling.) Snell: I gave a talk this week about muscle fiber types and diabetes. But the same sort of idea applies. And that is, we think that a lot of people who’ve got diabetes have got a lot of these type 2 muscle fibers that have never been used. They used to be called type 2b, now they’re called type 2x. But they don’t get recruited in activity unless the exercise is a fairly high intensity. Because in the recruitment of muscle fibers, the slow- twitch get activated first, and then the type 2a’s, and then finally the type 2b. So if you want to get them more adapted for endurance, then you actually have to work at a rate that activates them and makes them work. So I think if someone is just plodding along slowly, they’re just sort of making their muscles, the fibers that are being used to do that, they’re certainly making them maybe a little bit better. But there’s heck of a lot of fibers that are just not called on because the intensity is too low, basically. Q: So there’s the slow-twitch and then the type 2a. Are they typically called fast- twitch? Snell: Yeah, fast-twitch. Type 2 is the fast-twitch. And there’s two types of those, and they’re distinguished by their metabolic properties. -

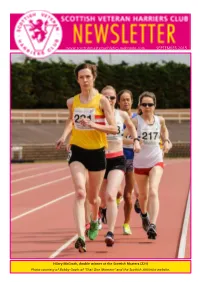

Svhc Newsletter Sept 15

www.scottishmastersathletics.webnode.com SEPTEMBER 2015 Hilary McGrath, double winner at the Scottish Masters (221) Photo courtesy of Bobby Gavin of ‘That One Moment’ and the Scottish Athletics website. MEMBERSHIP NOTES 20th August 2015 MEMBERS CLUB VESTS I regret to report that 2 of our life members have died recently. Vests can be purchased from Andy Law for £18, including Bill Stoddart passed away on 10th August, aged 84. He postage. (Tel: 01546 605336. or email [email protected]) had been a member of SVHC since 1971 and was made an NEW MEMBERS honorary life member in 2003. Bill was profiled in our April 2014 Newsletter. We send our sympathy to his wife Betty, Alastair Beaton 13-May-15 2246 Inverness their son Donald, daughter-in-law Josephine and grandsons Suzanne Boyle 28-Jun-15 2256 Glasgow Jack and Tom. Anya Campbell 18-Jul-15 2263 Galashiels Our Hon Life President Bob Donald passed away on 16th Justin Carter 21-Jul-15 2264 Glasgow August, aged 88. He was 1 of the original SVHC Members. Sean Casey 13-May-15 2247 Cumbernauld Welcome to the 29 new and 9 reinstated members who have Alison Dargie 12-Aug-15 2270 Gosforth joined or re-joined since 10th March 2015. 57 members did Anne Douglas 26-May-15 2251 Balerno not renew their subs. As of 20th August 2015, we have 473 Cameron Douglas 24-Mar-15 2244 Dumfries paid up members . Brian Douglas 16-Aug-15 2271 Glasgow For those who have not already paid or set up standing Agnes Ellis 31-May-15 2250 Glasgow orders, subscription renewals are due in October for 2015/16. -

Amateurism and Coaching Traditions in Twentieth Century British Sport

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Uneasy Bedfellows: Amateurism and Coaching Traditions in Twentieth Century British Sport Tegan Laura Carpenter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2012 Tegan Carpenter July 2012 If you do well in sport and you train, ‘good show’, but if you do well in sport and you don’t train, ‘bloody good show’. Geoffrey Dyson, 1970 Tegan Carpenter July 2012 Dedication This thesis is proudly dedicated to my parents, Lynne and John, my two brothers, Dan and Will and my best friend, Steve - Thank you for always believing in me. Tegan Carpenter July 2012 Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the continued support of family, friends and colleagues. While I am unable to acknowledge you all individually - I will be forever indebted to you. To my supervisor, Dr Dave Day - I consider myself incredibly lucky to have had such an attentive and committed mentor. Someone who transformed the trudge of a PhD into an enjoyable journey, and because of this, I would not hesitate accepting the opportunity again (even after knowing the level of commitment required!). Thank you for never losing faith in me and for your constant support and patience along the way. I would also like to thank Dr Neil Carter and Professor Martin Hewitt for their comments and advice. Special thanks to Sam for being the best office buddy and allowing me to vent whenever necessary! To Margaret and the interviewees of this study – thank you for your input and donating your time. -

Our Part in Four-Minute Mile History

Our part in four-minute mile history Bruce McAvaney addressed a dinner in Melbourne recently, to commemorate Australian John Landy's first sub-four-minute mile and world record, run 50 years ago, six weeks after Roger Bannister first went under four. This is the transcript of his speech. "Here is the result of event No.9, the one mile: No. 41, R G Bannister, of the Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, with a time that is a new meeting and track record, and which, subject to ratification, with be a new English native, British National, British all-comers, European, British Empire and World Record. The time is 3…." That's arguably the most famous cue, let alone understated announcement in athletics history…3 Minutes, 59.4 seconds! He was a formidable character, the announcer. Norris McWhirter died earlier this year, unfortunately just before the 50th anniversary of the first sub-four minute mile. McWhirter apparently had rehearsed assiduously the night before, in his bath, and it was through him that the BBC, the newsreel camera and most of the print media were present that day. McWhirter, and his twin Ross, who was gunned down in 1975 by the IRA, were joint founders and editors of the Guinness Book of Records. McWhirter had a sense of humour. Here in Melbourne at the 1956 Olympics, he told the story of a middle-aged Australian woman who, observing distressing scenes at the finish of the marathon exclaimed, "Cripes, how many qualify for the final?"… Back to Bannister, and the race: is it the sport's finest achievement? How does the 3.59.4 stack up with other athletic landmarks? Classics such as our own Ron Clarke's 27:39.4 in Oslo in 1965, a 35 second improvement on the previous mark. -

April 2021 to Get Involved with This Exciting Opportunity

As an Olympian View this email in your browser Dear <<First Name>>, This quarter we have lots to share with you: Message from the Olympians' Commission Chair - Chantal Brunner Profile - Olympians' Commission Member - Martin Brill Believe in Sport Appointment - Alexis Pritchard Olympic Day - June 23rd TOKYO 2020 UPDATES NZ Team Preparation The Great Olympic Skate - Get on Board Olympian Discount on NZ Team Merchandise OLYMPIAN EDUCATION & OPPORTUNITIES Power Up Workshop Adecco Job Opportunity AirBnB Experiences Business Accelerator Workshop Otago Medical School Survey FACE BOOK PAGE WHERE ARE THEY NOW? - Barry Magee OBITUARIES Message from the Olympians' Commission Chair Kia ora koutou, April 14 marked 100 days until the opening of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. As the date of the Opening Ceremony approaches, and athlete selection announcements begin to flow, we look forward to welcoming new Olympians into the New Zealand Olympian whanau. It’s clear that these Games will be conducted in challenging circumstances. Our athletes are preparing for a tough and very different Olympic Games experience. News that international spectators will not be able to attend the Games (while understandably necessary) is a blow, especially for competing athletes and their families. Because of these international travel restrictions, NZOC and its partners have sought new ways for New Zealanders to show their support. Some fantastic national and regional events are planned (we had a sneak preview at our last Olympians Commission meeting. Read more below about the Great Olympic Skate Roadshow which will be visiting 40 towns in 41 days, kicking off on Monday May 10th, with Olympians from all Games set to join for parts of the journey. -

All Time Men's World Ranking Leader

All Time Men’s World Ranking Leader EVER WONDER WHO the overall best performers have been in our authoritative World Rankings for men, which began with the 1947 season? Stats Editor Jim Rorick has pulled together all kinds of numbers for you, scoring the annual Top 10s on a 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 basis. First, in a by-event compilation, you’ll find the leaders in the categories of Most Points, Most Rankings, Most No. 1s and The Top U.S. Scorers (in the World Rankings, not the U.S. Rankings). Following that are the stats on an all-events basis. All the data is as of the end of the 2019 season, including a significant number of recastings based on the many retests that were carried out on old samples and resulted in doping positives. (as of April 13, 2020) Event-By-Event Tabulations 100 METERS Most Points 1. Carl Lewis 123; 2. Asafa Powell 98; 3. Linford Christie 93; 4. Justin Gatlin 90; 5. Usain Bolt 85; 6. Maurice Greene 69; 7. Dennis Mitchell 65; 8. Frank Fredericks 61; 9. Calvin Smith 58; 10. Valeriy Borzov 57. Most Rankings 1. Lewis 16; 2. Powell 13; 3. Christie 12; 4. tie, Fredericks, Gatlin, Mitchell & Smith 10. Consecutive—Lewis 15. Most No. 1s 1. Lewis 6; 2. tie, Bolt & Greene 5; 4. Gatlin 4; 5. tie, Bob Hayes & Bobby Morrow 3. Consecutive—Greene & Lewis 5. 200 METERS Most Points 1. Frank Fredericks 105; 2. Usain Bolt 103; 3. Pietro Mennea 87; 4. Michael Johnson 81; 5.