Starting a Conversation: the Effort, Effect and Affect of Trans Poetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiction ISBN 978-1-55152-725-3 $17.95 Canada | $15.95 USA Arsenal Pulp Press

“You’re gonna need a rock and a whole lotta medicine” Whitehead is a mantra that Jonny Appleseed, a young Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer and NDN glitter princess, Joshua Joshua repeats to himself in this vivid and utterly compelling debut novel by Joshua Whitehead. Off the rez and trying to find ways to live, love, and survive in the big city, Jonny has one week before he must return to his home—and his former life—to attend the funeral of his stepfather. The seven days that follow are like a fevered dream: stories of love, trauma, sex, kinship, ambition, and heartbreaking recollections of his beloved kokum (grandmother). Jonny’s life is a series of breakages, appendages, and linkages—and as he goes through the motions of preparing to return home, he learns how to put together the pieces of his life. JONNY APPLESEED HIGHLIGHTS Jonny Appleseed is a unique, shattering vision of Indigenous life, full of grit, glitter, and dreams. “Joshua Whitehead redefines what queer Indigenous writing can be in his powerful debut novel. Jonny Appleseed transcends genres of writing to blend the sacred and the sexual into a vital expression of Indigenous desire and love. Reading it is a coming home to bodies, stories, and experiences of queer Indigenous life that has never been so richly and honestly shown before. This book is an honour song to every queer NDN body who has ever lived and it will transform the universe with its beauty and magic.” FROM THE BACKLIST —Gwen Benaway, author of Passage “If we’re lucky, we’ll find one or two books in a lifetime that change the language of story, that manage to illuminate new curves in the flat vessels of old letters and words. -

From “Telling Transgender Stories” to “Transgender People Telling Stories”: Transgender Literature and the Lambda Literary Awards, 1997-2017

FROM “TELLING TRANSGENDER STORIES” TO “TRANSGENDER PEOPLE TELLING STORIES”: TRANSGENDER LITERATURE AND THE LAMBDA LITERARY AWARDS, 1997-2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Andrew J. Young May 2018 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Dustin Kidd, Advisory Chair, Sociology Dr. Judith A. Levine, Sociology Dr. Tom Waidzunas, Sociology Dr. Heath Fogg Davis, External Member, Political Science © Copyright 2018 by Andrew J. Yo u n g All Rights Res erved ii ABSTRACT Transgender lives and identities have gained considerable popular notoriety in the past decades. As part of this wider visibility, dominant narratives regarding the “transgender experience” have surfaced in both the community itself and the wider public. Perhaps the most prominent of these narratives define transgender people as those living in the “wrong body” for their true gender identity. While a popular and powerful story, the wrong body narrative has been criticized as limited, not representing the experience of all transgender people, and valorized as the only legitimate identifier of transgender status. The dominance of this narrative has been challenged through the proliferation of alternate narratives of transgender identity, largely through transgender people telling their own stories, which has the potential to complicate and expand the social understanding of what it means to be transgender for both trans- and cisgender communities. I focus on transgender literature as a point of entrance into the changing narratives of transgender identity and experience. This work addresses two main questions: What are the stories being told by trans lit? and What are the stories being told about trans literature? What follows is a series of separate, yet linked chapters exploring the contours of transgender literature, largely through the context of the Lambda Literary Awards over the past twenty years. -

Pride Collection Brochure

2SLGBTQ+ BOOKS & DVDs PICTURE BOOKS Diversity: Gay: All Families Are Special by Norma Simon From Archie to Zak by Vincent Kirsch A Church for All by Gayle E. Pitman Ghost’s Journey by Robin Stevenson Families, Families, Families by Suzanne Lang Harriet Gets Carried Away by Jessie Sima The Family Book by Todd Parr Jerome by Heart by Thomas Scotto A Family Is a Family Is a Family by Sara O’Leary Old Macdonald Had a Baby by Emily Snape Over the Shop by JonArno Lawson A Plan for Pops by Heather Smith Pride Puppy by Robin Stevenson Prince and Knight by Daniel Haack This Day in June by Gayle E. Pitman Stella Brings the Family by Miriam B. Schiffer A Tale of Two Daddies by Vanita Oelschlager And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson Uncle Bobby’s Wedding by Sarah S. Brannen Lesbian: Asha’s Mums by Rosamund Elwin Donovan’s Big Day by Lesléa Newman Happy Birthday, Alice Babette by Monica Culling Heather Has Two Mommies by Lesléa Newman In Our Mothers’ House by Patricia Polacco Plenty of Hugs by Fran Manushkin Gender Nonconforming & Nonbinary: Angus All Aglow by Heather Smith From the Stars In the Sky to the Fish in the Sea by Kai Cheng Thom I Love My Purse by Belle DeMont Introducing Teddy by Jessica Walton Julián is a Mermaid by Jessica Love Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress by Christine Baldacchino Red: A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall William’s Doll by Charlotte Zolotow Worm Loves Worm by J.J. Austrian BOARD BOOKS Daddy, Papa and Me by Lesléa Newman Mommy, Mama and Me by Lesléa Newman Pride Colors by Robin Stevenson JUVENILE GRAPHIC NOVELS The Breakaways by Cathy G. -

Sunday, September 22, 2019 10Am-5Pm | Harbourfront Centre

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2019 10AM-5PM | HARBOURFRONT CENTRE Celebrating Reading. Advocating Literacy. @torontoWOTS • #WOTS30 • thewordonthestreet.ca/toronto WANT TO WRITE? THE HUMBER SCHOOL FOR WRITERS’ CORRESPONDENCE PROGRAM Creative Writing – Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction, Poetry Looking for personalized feedback on your new manuscript? The Humber School for Writers’ Correspondence Program can help! Our 30-week distance studio program is customized to address the needs of your book-length project. Work from the comfort of home under guidance of our exceptional mentors. Apply as soon as possible in order to improve your chance of being paired with your preferred mentor: · David Bergen · Ashley Little · Giles Blunt · Colin McAdam · Karen Connelly · Pamela Mordecai · Elisabeth de Mariaffi · Tim Wynne-Jones · Elizabeth Duncan · Alissa York · Camilla Gibb APPLY NOW FOR JAN 2020! humberschoolforwriters.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 WANT TO WRITE? HOW TO USE THIS PROGRAM Review the Festival at a Glance on pages 8–12, or go directly to the venue THE HUMBER SCHOOL FOR descriptions. Want to see our kids programming? Pick up a TD Kidstreet guide at WOTS! WRITERS’ CORRESPONDENCE PROGRAM Creative Writing – Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction, Poetry WELCOME TO WOTS 2 MEET THE TEAM 3 LETTERS OF GREETING 4-5 Looking for personalized feedback on your new manuscript? FESTIVAL PARTNERS 6-7 FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE 8-12 The Humber School for Writers’ Correspondence Program can ASL PROGRAMMING 13-14 help! Our 30-week distance studio program is customized to #WOTS30 ANNIVERSARY SERIES 15 OFFICIAL BOOKSELLERS 16 address the needs of your book-length project. Work from the AMAZON.CA BESTSELLERS 18-24 comfort of home under guidance of our exceptional mentors. -

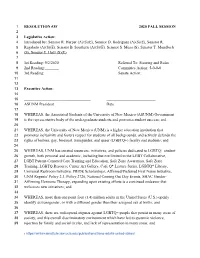

Senator D. Rodriguez (A)(S)(E), Senator R

1 RESOLUTION #3F 2020 FALL SESSION 2 3 Legislative Action: 4 Introduced by: Senator R. Harper (A)(S)(E), Senator D. Rodriguez (A)(S)(E), Senator R. 5 Regalado (A)(S)(E), Senator B. Southern (A)(S)(E), Senator S. Musa (S), Senator T. Mondloch 6 (S), Senator E. Hotz (S)(E) 7 8 1st Reading: 9/2/2020 Referred To: Steering and Rules 9 2nd Reading:_______ Committee Action: 5-0-0-0 10 3rd Reading: _______ Senate Action:___________ 11 12 13 Executive Action: 14 15 __________________________________ _________________________ 16 ASUNM President Date 17 18 WHEREAS, the Associated Students of the University of New Mexico (ASUNM) Government 19 is the representative body of the undergraduate students and promotes student success; and 20 21 WHEREAS, the University of New Mexico (UNM) is a higher education institution that 22 promotes inclusivity and fosters respect for students of all backgrounds, and actively defends the 23 rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) faculty and students; and 24 25 WHEREAS, UNM has curated resources, initiatives, and policies dedicated to LGBTQ+ student 26 growth, both personal and academic, including but not limited to the LGBT Collaborative, 27 LGBT Patient-Centered Care Training and Education, Safe Zone Awareness, Safe Zone 28 Training, LGBTQ Resource Center Art Gallery, Cafe Q* Lecture Series, LGBTQ* Library, 29 Universal Restroom Initiative, PRIDE Scholarships, Affirmed/Preferred First Name Initiative, 30 UNM Regents' Policy 2.3, Policy 2720, National Coming Out Day Events, SHAC Gender- 31 -

SLW Title List 2020-11-06

Short Literary Works Title List (2020-11-06) ID ISBN Name Author Publisher Pub. Year 15953 9781551526416 even this page is white Vivek Shraya Arsenal Pulp Press 2016 16224 9781551527536 Double Melancholy C.E. Gatchalian Arsenal Pulp Press 2019 16290 9781551527550 Shut Up You're Pretty Téa Mutonji Arsenal Pulp Press 2019 16387 9781551527819 Hustling Verse Amber Dawn, Justin DucharmeArsenal Pulp Press 2019 16691 9781551527758 I Hope We Choose Love Kai Cheng Thom Arsenal Pulp Press 2019 16718 9781551527598 Disintegrate/Dissociate Arielle Twist Arsenal Pulp Press 2019 16750 9781551527574 Tonguebreaker Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-SamarasinhaArsenal Pulp Press 2019 16791 9781988168111 At Bay Press Fiction Annual Sabrina Lightstone At Bay Press 2017 16868 9780991761081 At Bay Press Fiction Annual Alana Brooker At Bay Press 2016 16905 9780991761005 At Bay Press Fiction Annual Alana Brooker At Bay Press 2013 My Conversations with 19288 9781771663601 Canadians Lee Maracle Book*hug Press 2017 Before I Was a Critic I Was a 19360 9781771665070 Human Being Amy Fung Book*hug Press 2019 19591 9781771662581 Notes from a Feminist Killjoy Erin Wunker Book*hug Press 2017 19623 9781771663069 Blank M. NoubeSe Philip Book*hug Press 2017 19740 9781771663731 The Unpublished City Dionne Brand Book*hug Press 2017 19857 9781771663922 Dear Current Occupant Chelene Knight Book*hug Press 2018 19904 9781771665438 Re-Origin of Species Alessandra Naccarato Book*hug Press 2019 20063 9781771666039 Write Across Canada Geoffrey Taylor, Joseph KertesBook*hug Press 2019 20115 -

Naked Heart Festival

GLAD DAY LIT PRESENTS The LGBTQ Festival of Words Financial support is absolutely crucial to build this tradition of bringing people together from across the North America. The organizations and people below have made it possible OUR VISION TO OUR COMMUNITIES to spread the word about Naked Heart, and more importantly, compensate our authors To establish a yearly Canadian LGBTQ How do we join a community we and speakers for sharing their gifts with us. We thank you for your generosty. literary festival that amplifies love, are not born into? How do we nuture language & freedom. our desires? How do we turn pain FESTIVAL FAIRY GODPARENT FESTIVAL SUPPORTER into love? How do we find each other? $2000+ Donation $75+ Donation OUR GOALS How do we build a better future? Glad Day Bookshop Sweets From The Earth • Strengthen literacies and the literary The answer for many of us is story. Amber Dawn community of LGBTQ people. FESTIVAL SUPERSTAR Anil Kamal What’s missing in our lesbian, gay, $1000+ Donation Billeh Nickerson • Create spaces for people to find new work, new opportunities, bi, trans, two-spirit and queer Buddies In Bad Times Carol Rosenfeld new friends and new lovers. communities? How do we create Brad Pyne Design Casey Oraa Michael Erickson Cherie Dimaline • Increase supports for under- space for possibility? Where do we Penguin Random House Christopher Gudgeon represented identities, experiences listen to each other when we don’t Faye Chisholm Guenther and forms of language. feel heard? How do we circulate Henderson Brewing Company FESTIVAL CATALYST • Build bridges between people of our own stories outside of industries Jessica L. -

Rainbows and Riots Pride Month @ Your Library

RAINBOWS AND RIOTS PRIDE MONTH @ YOUR LIBRARY Elisabeth Hegerat Manager: Community & Economic Advancement Lethbridge Public Library Photo credit :Derrick Antson ABOUT ME LETHBRIDGE PRIDE FEST ABOUT THE PHOTOS – MY COMMUNITY All photos of people are: • From Lethbridge, • Photos of library staff during work hours or, • Photos of Pride Fest board members or, • Performers, presenters, or others in an official capacity or, • Photos of individuals I know personally and have cleared it with them or, • Crowd scenes at public events. ABOUT THE LGBTQ+ COMMUNITY Lethbridge Flag Raising 2018 GENDER IDENTITY AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION “Sexual orientation is who you go to bed with. Gender identity is who you go to bed as.” - Tif Semach, OUTreach Southern Alberta, Queer 101 TERMINOLOGY – ALPHABET SOUP GLBT/LGBT • QUILTBAG • QUeer LGBTPQQ2SIAA • Intersex Lesbian • Lesbian Gay • Trans Bisexual • Bisexual Trans(gender) • Asexual/Allies Pansexual • Gay Queer Questioning • SOGI minorities • Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity 2 Spirit Intersex • Queer Asexual/Aromantic/Agender Allies • LGBTQ+ ETIQUETTE Don't out anyone/etiquette of coming out Just get rid of the word preference/preferred Straight pride: not a thing No-one likes to be the token Don't assume all gay people know each other Use the terms the individual person uses Ditto for pronouns Just be normal about it If you screw up, it's not about you I was reading a book (about interjections, oddly enough) yesterday which included the phrase “In these days of political correctness…” talking about no longer making jokes that denigrated people for their culture or for the colour of their skin. And I thought, “That’s not actually anything to do with ‘political correctness’. -

Garcia Zarranz (298.4Kb)

Forthcoming Peer-Reviewed Journal Article University of Toronto Quarterly 88 (Forthcoming Fall 2019) 27pp. Accepted on 17/12/2018 Feeling Sideways: Shani Mootoo and Kai Cheng Thom’s Sustainable Affects History grows itself from the side, from what is to the side of it—often in fictions—before it takes this sideways growth…to itself. —Kathryn Bond Stockton (2009) There’s something very, very powerful about feeling through art, being made to feel through art. —Shani Mootoo in Tara-Michelle Ziniuk (2015) love me for my anger…love me for my need. love me for my jealousy, my weakness, my greed, my cruelty, my viciousness, my shame. —Kai Cheng Thom, “inside voice” (2017) Affects are unruly: like adventurous children, they play hide and seek, always moving in multidirectional ways; like fleshy ghosts, we feel their presence and their absence, but they escape mapping, so any attempt to theorize affect necesarily entails pauses, delays, and breaks. Following transgender theorist Lucas Crawford (2015), I do not seek to locate affect inside the subject. Instead, I propose to read affects as dislocated transtemporal assemblages of intensities and forces caught in endless circuits of power and thus, of political, cultural, and ethical relevance. As Eve K. Sedgwick, Sara Ahmed, and many other queer and anti-racist theorists have taught us, affects such as happiness, love, and joy can become normative when they are imposed to sustain official narratives of whiteness, compulsory heterosexuality, national affiliation, or belonging. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Ahmed contends that “[l]oves that depart from the scripts of normative existence can be seen as a ‘source’ of shame. -

Further Toward Minor Literatures

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 9-2021 Further Toward Minor Literatures Aaron Hammes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4446 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FURTHER TOWARD MINOR LITERATURES by AARON HAMMES A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 i Copyright 2021 AARON HAMMES All Rights Reserved ii Further Toward Minor Literatures By Aaron Hammes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 6/23/2021 Tanya Agathocleous Chair of Examining Committee 6/28/2021 Kandice Chuh Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Tanya Agathocleous Jonathan Gray John Brenkman THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Further Toward Minor Literatures By Aaron Hammes Advisor: Tanya Agathocleous Further Toward Minor Literatures Aaron Hammes Minor literature is literatures of the minoritarian, not simply that produced by (cultural, ethnic, racial, gender-expressive, sexual, ability, age) minorities. Further Toward Minor Literatures operates from this decisive distinction to trace the contours and potentialities of one minoritarian literature, the contemporary transgender novel in the US and Canada. This study is premised in part on putting the fiction itself on a plane with theoretical and critical sources, creating a dialogue that does not privilege one discourse over the other. -

2017 New LGBTQ+ Adult Books

Me, Him, Muhammad Ali Randa Jarrar 2016 LGBTQ Sarabande Books Bisexual Interest Group I’m Just a Person Tig Notaro 2016 Ecco Lesbian Even This Page is White New Vivek Shraya 2016 Arsenal Pulp Press LGBTQ Trans, Bisexual Adult Books Small Beauty 2017 jia qing wilson-yang 2016 British Columbia Library Association Metonymy Press https://bclaconnect.ca/ Trans Join the LGBTQ Interest Group List-Serve: http://www.bclibraries.ca/listservs/bcla/ The Angel of History Rabih Alameddine Check out our Website 2016 https://bclalgbtq.wordpress.com/ Atlantic Monthly Press Gay Follow us on Twitter @BCLA_LGBTQ Buffering: Unshared Tales of a Life Here Comes the Sun A Two-Spirit Journey: The Fully Loaded Nicole Dennis-Benn Autobiography of a Lesbian Ojibwa- Hannah Hart 2016 Cree Elder 2016 Ma-Nee Chacaby Liveright Dey Street Books 2016 Lesbian University of Manitoba Press Lesbian Lesbian The Case of Alan Turing: The Extraordinary and Tragic Story of Passage Weekend the Legendary Codebreaker Gwen Benaway Jane Eaton Hamilton Éric Liberge 2016 2016 2016 Kegedonce Press Arsenal Pulp Press Arsenal Pulp Press Trans Lesbian, Trans Gay Life Beyond My Body: A When Watched: Stories Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: Transgender Journey to Leopoldine Core A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Manhood in China 2016 Confabulous Memoir Lei Ming Penguin Books Kai Cheng Thom 2016 Bisexual 2016 Transgress Press Metonymy Press Trans Trans Mouth to Mouth Everything is Awful and Jazz Moon Abigail Child You’re a Terrible Person Joe Okonkwo 2016 Daniel Zomparelli 2016 Eoagh Books 2017 Kensington Bisexual Arsenal Pulp Press Gay Gay Love Beyond Body, Space, and Black Deutschland Surpassing Certainty: What My Time: An Indigenous LGBT Sci-Fi Darryl Pinckney Twenties Taught Me Anthology 2016 Janet Mock Edited by Hope Nicholson Farrar, Straus, and Giroux 2017 2016 Gay Atria Books Bedside Press Trans LGBT . -

F20-APP-Catalogue.Pdf

plett casey lindsay wong lindsay wong WOO-WOO THE Little Fish is the stunning debut novel “You’re gonna need a rock and a whole lotta medicine” Whitehead Lindsay Wong grew up with a paranoid schizophrenic grandmother and a mother by the author of the Lambda Literary is a mantra that Jonny Appleseed, a young Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer and NDN glitter princess, Award-winning story collection Joshua who was deeply afraid of the “woo-woo”—Chinese ghosts who visit in times of personal repeats to himself in this vivid and utterly compelling debut novel by Joshua Whitehead. turmoil. When Lindsay was six, she and her mother avoided the dead people haunting A Safe Girl to Love. their house by hiding out in a mall food court, and on a camping trip, Lindsay’s mother Off the rez and trying to find ways to live, love, and survive in the big city, Jonny has one tried to rid her daughter of demons by lighting her foot on fire. It’s the dead of winter in Winnipeg and Wendy week before he must return to his home—and his former life—to attend the funeral of his Reimer, a thirty-year-old trans woman, feels like her stepfather. The seven days that follow are like a fevered dream: stories of love, trauma, sex, The eccentricities take a dark turn when her aunt holds the city hostage for eight hours life is frozen in place. When her Oma passes away kinship, ambition, and heartbreaking recollections of his beloved kokum (grandmother). Wendy receives an unexpected phone call from a Jonny’s life is a series of breakages, appendages, and linkages—and as he goes through the threatening to jump off a bridge.