Climate Change, Globalization, and Other “Modern” Issues in Ancient Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkey-Continues-To-Weaponize-Alok

www.stj-sy.org Turkey Continues to Weaponize Alok Water amid COVID-19 Outbreak in Syria Turkey Continues to Weaponize Alok Water amid COVID-19 Outbreak in Syria Turkey hampers the urgent response to Coronavirus Pandemic by cutting off water to over 600.000 population in northeast Syria Page | 2 www.stj-sy.org Turkey Continues to Weaponize Alok Water amid COVID-19 Outbreak in Syria 1. Legal analysis a) International Humanitarian Law Water is indispensable to civilian populations. It is not only essential to drink, but also for agricultural purposes and sanitation, all the more important in the wake of the COVID-19 sanitary crisis. Although at first neglecting the significance of water and food for civilian populations caught in armed conflicts, drafters of the Geneva Conventions’ Protocol remedied the gap by including, in Article 54 Additional Protocol I and in Article 14 Additional Protocol II for International and Non-International Armed Conflicts (IACs and NIACs) respectively, the protection of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population. Involving two states, that of Syria and that of Turkey, the ongoing conflict currently taking place in northeast Syria is of international character. As a result, and in application of these provisions, in IACs: It is prohibited to attack, destroy, remove or render useless objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, such as foodstuffs, agricultural areas for the production of foodstuffs, crops, livestock, drinking water installations and supplies and irrigation works, for the specific purpose of denying them for their sustenance value to the civilian population or to the adverse Party, whatever the motive, whether in order to starve out civilians, to cause them to move away, or for any other motive. -

Ancient Near Eastern Studies

Ancient Near Eastern Studies Studies in Ancient Persia Receptions of the Ancient Near East and the Achaemenid Period in Popular Culture and Beyond edited by John Curtis edited by Lorenzo Verderame An important collection of eight essays on and Agnès Garcia-Ventura Ancient Persia (Iran) in the periods of the This book is an enthusiastic celebration Achaemenid Empire (539–330 BC), when of the ways in which popular culture has the Persians established control over the consumed aspects of the ancient Near East whole of the Ancient Near East, and later the to construct new realities. It reflects on how Sasanian Empire: stone relief carvings from objects, ideas, and interpretations of the Persepolis; the Achaemenid period in Baby- ancient Near East have been remembered, lon; neglected aspects of biblical archaeol- constructed, re-imagined, mythologized, or ogy and the books of Daniel and Isaiah; and the Sasanian period in Iran (AD indeed forgotten within our shared cultural memories. 250–650) when Zoroastrianism became the state religion. 332p, illus (Lockwood Press, March 2020) paperback, 9781948488242, $32.95. 232p (James Clarke & Co., January 2020) paperback, 9780227177068, $38.00. Special Offer $27.00; PDF e-book, 9781948488259, $27.00 Special Offer $31.00; hardcover, 9780227177051, $98.00. Special Offer $79.00 PDF e-book, 9780227907061, $31.00; EPUB e-book, 9780227907078, $30.99 Women at the Dawn of History The Synagogue in Ancient Palestine edited by Agnete W. Lassen Current Issues and Emerging Trends and Klaus Wagensonner edited by Rick Bonnie, Raimo Hakola and Ulla Tervahauta In the patriarchal world of ancient This book brings together leading experts in the field of ancient-synagogue Mesopotamia, women were often studies to discuss the current issues and emerging trends in the study of represented in their relation to men. -

Giorgio Buccellati

Il passato ha un’importanza che dura nel tempo. Questo è il filo conduttore del presente libro, come della mostra a cui si accompagna. Giorgio Buccellati La domanda fondamentale che il percorso affronta è: qual è il legame solidale che mantiene uniti i gruppi umani? Nel testo quindi si presentano alcune fasi dello sviluppo della capacità umana di vivere insieme, dal più antico Paleolitico (rappresentato dagli ominini di Dmanisi Giorgio Buccellati nell’odierna Georgia) all’inizio della civiltà (illustrata dal sito di Urkesh in Siria), per concludere con una presentazione dell’importanza dell’archeologia come di- Dal profondo sciplina costruttrice di unità nazionale nella Siria dei giorni nostri. All’origine Oltre a descrivere i dati, la ricerca propone modi di avvicinarsi a un’esperienza della comunicazione umana che, pur interrotta dal profondo distacco temporale, è tuttora viva nei e della comunità valori che impersonava e che vi vuole ancora trasmettere. del nell’antica Siria Un ricco corredo iconografico accompagna i testi, impreziosito da alcuni scatti tratti dalla collezione di Kenneth Garrett (incluso quello di copertina), uno dei più prestigiosi fotografi americani, noto sopratuttto per la sua collaborazione con il «National Geographic». tempo GIORGIO BUCCELLATI è Professor Emeritus nei due dipartimenti di lingue vicino orientali e di storia presso l’Università di California a Los Angeles (UCLA), dove inse- premessa di gna tuttora. Nel 1973 ha fondato l’Istituto di Archeologia (oggi il Cotsen Institute Dal profondo del tempo Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati of Archaeology), di cui fu il primo direttore fino al 1983, e dove è ora Research Pro- fessor e direttore del Laboratorio Mesopotamico. -

Syria 2014 Human Rights Report

SYRIA 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The authoritarian regime of President Bashar Asad has ruled the Syrian Arab Republic since 2000. The regime routinely violated the human rights of its citizens as the country witnessed major political conflict. The regime’s widespread use of deadly military force to quell peaceful civil protests calling for reform and democracy precipitated a civil war in 2012, leading to armed groups taking control of major parts of the country. In government-controlled areas, Asad makes key decisions with counsel from a small number of military and security advisors, ministers, and senior members of the ruling Baath (Arab Socialist Renaissance) Party. The constitution mandates the primacy of Baath Party leaders in state institutions and society. Asad and Baath party leaders dominated all three branches of government. In June, for the first time in decades, the Baath Party permitted multi-candidate presidential elections (in contrast to single-candidate referendums administered in previous elections), but the campaign and election were neither free nor fair by international standards. The election resulted in a third seven-year term for Asad. The geographically limited 2012 parliamentary elections, won by the Baath Party, were also neither free nor fair, and several opposition groups boycotted them. The government maintained effective control over its uniformed military, police, and state security forces but did not consistently maintain effective control over paramilitary, nonuniformed proregime militias such as the National Defense Forces, the “Bustan Charitable Association,” or “shabiha,” which often acted autonomously without oversight or direction from the government. The civil war continued during the year. -

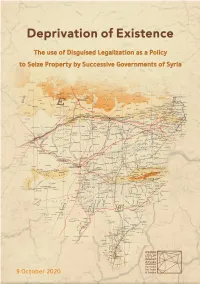

In PDF Format, Please Click Here

Deprivatio of Existence The use of Disguised Legalization as a Policy to Seize Property by Successive Governments of Syria A special report sheds light on discrimination projects aiming at radical demographic changes in areas historically populated by Kurds Acknowledgment and Gratitude The present report is the result of a joint cooperation that extended from 2018’s second half until August 2020, and it could not have been produced without the invaluable assistance of witnesses and victims who had the courage to provide us with official doc- uments proving ownership of their seized property. This report is to be added to researches, books, articles and efforts made to address the subject therein over the past decades, by Syrian/Kurdish human rights organizations, Deprivatio of Existence individuals, male and female researchers and parties of the Kurdish movement in Syria. Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) would like to thank all researchers who contributed to documenting and recording testimonies together with the editors who worked hard to produce this first edition, which is open for amendments and updates if new credible information is made available. To give feedback or send corrections or any additional documents supporting any part of this report, please contact us on [email protected] About Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) STJ started as a humble project to tell the stories of Syrians experiencing enforced disap- pearances and torture, it grew into an established organization committed to unveiling human rights violations of all sorts committed by all parties to the conflict. Convinced that the diversity that has historically defined Syria is a wealth, our team of researchers and volunteers works with dedication at uncovering human rights violations committed in Syria, regardless of their perpetrator and victims, in order to promote inclusiveness and ensure that all Syrians are represented, and their rights fulfilled. -

Pope Francis : “We Were Not Norn ‘Flawed.’ Publishers (Editore): Our Nature Is Made for Great Things” 9 Società Coop

cover0815_Layout 1 22/09/15 15.15 Pagina 1 C O M M U N I O N A N D L I B E R A T I O N I N T E R N A T I O N A L M A G A Z I N E 5 1 0 2 8 VOL. 17 L I T T E R A E C O M M U N I O N I S THE SPARK News from the Rimini Meeting dedicated to the “thirst for infinity” that shows how an encounter can reawaken one’s humanity. CONTENTS September, 2015 Vol.17 - No. 8 PAGE ONE Communion and Liberation International Magazine - Vol. 17 THE CHOICE OF Editorial Office: Via Porpora, 127 - 20131 Milano ABRAHAM AND Tel. ++39(02)28174400 Fax ++39(02)28174401 THE CHALLENGES E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.tracesonline.org OF THE PRESENT Editor (direttore responsabile): Notes from the dialogue between Julián Carrón, Davide Perillo Joseph H.H. Weiler and Monica Maggioni Vice-editor: Paola Bergamini at the Meeting for Friendship Among Peoples. Editorial Assistant: Rimini, August 24, 2015 Anna Leonardi From New York, NY: Stephen Sanchez Editorial Just as in the Beginning 3 Graphic Design: G&C, Milano Davide Cestari, Lucia Crimi Letters Edited by Paola Bergamini 4 Photo: Archivio Meeting: cover, 6/15; Immagini tratte dalla mostra del Meeting di Rimini: “Abramo. La nascita dell’io”: 16/27; Close Up Meeting The Spark of the Unexpected by Davide Perillo 6 C. Campagner: 28/31 Pope Francis : “We Were not Norn ‘Flawed.’ Publishers (editore): Our Nature Is Made for Great Things” 9 Società Coop. -

The Mythological Background of Three Seal Impressions Found in Urkesh

XXII/2014/1/Studie The Mythological Background of Three Seal Impressions Found in Urkesh TIBOR SEDLÁčEK* Archeological work on the Syrian Tell Mozan site began in the year 1984 under the lead of Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati. The site was convincingly identified with the ancient northern Mesopotamian city of Urkesh. A significant part of the archeological evi- dence found at this site has Hurrian characteristics1 and can therefore be used to complement the image of early Hurrian history and culture.2 As * This text was completed in the framework of the project “Epistemological problems in research in the study of religions” (project No. MUNI/A/0780/2013). I would like to thank my Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Dalibor Papoušek, for his important remarks. My special thanks go to Dr. David Zbíral for his thoughtful corrections and suggestions. I also thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. All remaining mis- takes are my own. 1 See especially Giorgio Buccellati, “Urkesh and the Question of Early Hurrian Urbanism”, in: Michaël Hudson – Baruch A. Levine (eds.), Urbanization and Land Ownership in the Ancient Near East: A Colloquium Held at New York University, November 1996, and the Oriental Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia, May 1997, (Peabody Museum Bulletin 7), Cambridge: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 1999, 229-250; id., “The Semiotics of Ethnicity: The Case of Hurrian Urkesh”, in: Jeanette C. Fincke (ed.), Festschrift für Gernot Wilhelm anläßlich seines 65. Geburtstages am 28. Januar 2010, Dresden: Islet Verlag 2010, 79-90; id., “When Were the Hurrians Hurrian? The Persistence of Ethnicity in Urkesh”, in: Joan Aruz – Sarah B. -

Tell Mozan/Urkesh (Syria): a Modern Face for an Ancient City Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati and Giorgio Buccellati CAMNES and Ldm, December 3, 2012

Tell Mozan/Urkesh (Syria): A Modern Face for an Ancient City Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati and Giorgio Buccellati CAMNES and LdM, December 3, 2012 The Excavation Project The excavations of the site of tell Mozan have been conducted by the UCLA archaeologists Giorgio Buccellati (who is also a member of the CAMNES scientific committee) and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati since 1984. Tell Mozan is the site of the ancient city of Urkesh – which was known from myth and history, and which the excavations have firmly placed its location in northeastern Syria. Its beginnings are yet th unknown, but they date back at least to the early phase of the 4 millennium B.C. It was a main center of the Hurrians, who celebrated it in their myths as the home of the father of the gods, Kumarbi. It was also the capital of a kingdom that controlled the highlands immediately to the north, where the supplies of copper were located and that made the city wealthy. Highest on its horizon is the temple of Kumarbi, dating to about 2400 B.C. The name of the king who built it – Tishatal, is known from two magnificent bronze lions. The temple stood on a vast terrace: only portions of the monumental revetment wall and of the even more monumental staircase have been brought to light – enough, though, to give a sense of the spectacular choreography the ancients had been able to create. Another important building discovered by the archaeologist is the ancient Royal Palace. In its present form it dates to a time slightly later than the Temple, about 2300 B.C. -

(CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA-021

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA-021 April 2017 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, William Raynolds, Allison Cuneo, Kyra Kaercher, Darren Ashby Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports Syria 9 Incident Reports Iraq 86 Incident Reports Libya 121 Satellite Imagery and Geospatial Analysis 124 Heritage Timeline 127 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● New video footage shows damage to al-Kabir Mosque in al-Bab, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0048 ● New video footage shows damage to al-Iman mosque in al-Bab, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0049 ● New photographs show cleanup and reconstruction efforts taking place at Beit Ghazaleh in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0050 ● New photographs show cleanup and reconstruction efforts taking place at the al-Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0051 ● New photographs show cleanup and reconstruction efforts taking place at Suq Wara al-Jame in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0052 ● Shells land near the National Museum in Damascus, Damascus Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0053 ● Reported SARG airstrikes severely damage al-Sahbat al-Abrar Mosque in Damascus, Damascus Governorate. -

Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures

Vol. 2 - 2020 Vol. Asia Anteriore Antica Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures 2611-8912 Vol. 2 - 2020 Asia Anteriore Antica Anteriore Asia Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures Journal of FIRENZE FUP PRESSUNIVERSITY Asia Anteriore Antica Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures Vol. 2 - 2020 Firenze University Press AsiAnA Asia Anteriore Antica Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures Scientific Director: Stefania Mazzoni Editorial Board Amalia Catagnoti, Anacleto D’Agostino, Candida Felli, Valentina Orsi, Marina Pucci, Sebastiano Soldi, Maria Vittoria Tonietti, Giulia Torri. Scientific Committee Abbas Alizadeh, Dominik Bonatz, Frank Braemer, Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Tim Harrison, Robert Hawley, Gunnar Lehmann, Nicolò Marchetti, Doris Prechel, Karen Radner, Ulf-Dietrich Schoop, Daniel Schwemer, Jason Ur. The volume was published with the contribution of Fondazione OrMe – Oriente Mediterraneo and Di- partimento SAGAS – Università di Firenze Front cover photo: Tell Brak, gold sheet pendant, Early Bronze Age, Deir ez-Zor Archaeological Museum (adapted from Aruz, Wallenfels (eds) 2003, fig. 158a). Published by Firenze University Press – University of Florence, Italy Via Cittadella, 7 - 50144 Florence - Italy http://www.fupress.com/asiana Direttore Responsabile: Vania Vorcelli Copyright © 2020 Authors. The authors retain all rights to the original work without any restrictions. Open Access. This issue is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Interna- tional License (CC-BY-4.0) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0) waiver applies to the data made available in this issue, unless otherwise stated. -

Ebla and the Amorites

Ebla and the Amorites GIORGIO BUCCELLATI The Terms of the Problem The Ebla querelle, if one may so term the sharply divergent opinions which have come to be voiced about the nature of the language and culture of third-millennium Ebla, is happily on the wane. Happily, because little scholarly benefit came from it; and on the wane, because the difficult task of philological documentation is absorbing the better part of the effort being currently expended in this area. While it is not my intent to review here any of the aspects of this affair, I will refer to it at certain junctures, from the following perspective: the internal dynamics of the querelle as a form of scholarly discourse has, in my view, led to a certain crystallization of substantive and methodological presup- positions, which have been at times accepted too soon and too uncritically. The resulting scholarly perception has to be taken into consideration as a sort of mindset which conditions the direction taken by the research, through the as- sumptions it posits (often tacitly) upstream of any interpretation. In other words, while the querelle may well have subsided, the factors which led to its coming into being are still operative and should be addressed on their scholarly merits. Two important objective factors1 are (1) the very early date of Ebla archives (Pre-Sargonic or early Sargonic) and (2) the fact that their findspot is found so far to the west of any other third-millennium cuneiform corpus. An important con- comitant factor should also be stressed, namely (3) the material consistency and homogeneity of the archives. -

The Monumental Temple Terrace at Urkesh and Its Setting

The Monumental Temple Terrace at Urkesh and its Setting Federico Buccellati, Frankfurt a.M. “The artist is he who fixes and renders accessible to the more ‘human’ of men the spectacle in which they are actors without realizing it” – Merleau-Ponty1 Introduction2 The Temple terrace at Tell Mozan3 is one of the most impressive structures discovered to date in third millennium Syria. It is a high terrace, consisting of a sloped ramp rising from the central plaza of the city, encircled by a three meter high stone revetment wall, from the top of which rises another sloping surface leading to a temple at the summit of the complex (Fig. 1). The stone staircase gives access directly from the plaza, cutting the revetment wall. From the plaza to the floor level of the temple there is a difference of 13 meters in elevation. This article will give the context of the Temple Complex within the city of Urkesh as well as the chronological span of the use period of the Com- 1 Merleau-Ponty 1962,37. Translation mine. 2 It is with great pleasure that I contribute this article to a volume dedicated to Jan- Waalke Meyer, who lead me to discover Arnheim. As so often, Arnheim came up in a discussion we had about architecture, where he brought in many disparate approaches. He offered, as is typical of his teaching, a range of interesting paths, letting the student follow any of these avenues. Additionally he has always shown a great sensitivity and interest in perception which I have appreciated, in particular when he is guiding visitors around his excavations at Chuera.