Us Naval Bases from 1898 To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two US Navy's Submarines

Now available to the public by subscription. See Page 63 Volume 2018 2nd Quarter American $6.00 Submariner Special Election Issue USS Thresher (SSN-593) America’s two nuclear boats on Eternal Patrol USS Scorpion (SSN-589) More information on page 20 Download your American Submariner Electronically - Same great magazine, available earlier. Send an E-mail to [email protected] requesting the change. ISBN List 978-0-9896015-0-4 American Submariner Page 2 - American Submariner Volume 2018 - Issue 2 Page 3 Table of Contents Page Number Article 3 Table of Contents, Deadlines for Submission 4 USSVI National Officers 6 Selected USSVI . Contacts and Committees AMERICAN 6 Veterans Affairs Service Officer 6 Message from the Chaplain SUBMARINER 7 District and Base News This Official Magazine of the United 7 (change of pace) John and Jim States Submarine Veterans Inc. is 8 USSVI Regions and Districts published quarterly by USSVI. 9 Why is a Ship Called a She? United States Submarine Veterans Inc. 9 Then and Now is a non-profit 501 (C) (19) corporation 10 More Base News in the State of Connecticut. 11 Does Anybody Know . 11 “How I See It” Message from the Editor National Editor 12 2017 Awards Selections Chuck Emmett 13 “A Guardian Angel with Dolphins” 7011 W. Risner Rd. 14 Letters to the Editor Glendale, AZ 85308 18 Shipmate Honored Posthumously . (623) 455-8999 20 Scorpion and Thresher - (Our “Nuclears” on EP) [email protected] 22 Change of Command Assistant Editor 23 . Our Brother 24 A Boat Sailor . 100-Year Life Bob Farris (315) 529-9756 26 Election 2018: Bios [email protected] 41 2018 OFFICIAL BALLOT 43 …Presence of a Higher Power Assoc. -

NSITREP 27 4 Mar 21.Indd

Issue #27 October 2004 Table of Contents Product Updates Update from AGS Features Changing Times 1 In Print H3 Single Player Harpoon Scenario: Taiwan Tripwire 2 The draft of Christoph Kluxen’s Baltic The Macintosh version 3.6.2.1 is in Annex A - Ships for Taiwan Tripwire 4 Arena is 90% complete, and will be available open beta, as is 3.6.2.2 of the PC product. An Imaginary Aircraft - Unfortunately 5 From “400 tonners” to “Flush Deckers” 6 for Cold Wars ‘05. Jay Wissmann and Bill We are setting our work list for version New Chinese Ship Classes 11 Madison are also making progress on the 3.6.3 of the game, especially bug fixes. FG&DN Scenario: The First Balkan War 12 DoRS Forms booklet, which should be ready Also for 3.6.3 we are working on making Annexes A & C1 for the First Balkan War 16 for the summer 2005 conventions. installation easier and producing an updated Q&A - Italian Gunnery in WW II 19 After that, we will begin pulling User’s Guide! Malvinas Follow-up 19 together Atlantic Navies and Stars & Stripes, CaS Scenario: A Slight Misunderstanding 20 our next planned CaS and Harpoon releases, H3 Multiplayer (MP) & Professional Annex A - Ships for respectively. (Pro) A Slight Misunderstanding 21 We are releasing new beta copies every Harpoon Scenario: Hormuz Station 22 Semper Paratus - US Coast Guard For the Computer week for testing and are trying very hard for Operations in Vietnam 1960 - 75 26 There have been a lot of “What’s next?” open beta of MP in September, and release Annexes for the USCG 1960 - 75 28 questions from players following Ubisoft’s of Pro to our lead military customers at the Rules Changes & Clarifications announcement that their computer Harpoon same time. -

November, 1932

5 NOVEMBER 1932. ** ** 4+ *4 ** ** 4+ ** ** - ** ** ++ 44 ** ** ++ lsPr ** ** PUBLISHED FOR THE PURPOSE OF DISSEMINATING GENERAL I NFORMAT I OM OF PROBABLE I NTEREST TO THE SERVICE. * OFFICER PERSONNEL SZLECTION BOARD i A Line Selection Board, composed of the foll@hg-named offi- cers will meet on 1 December, 1932, to select nine captains and . twenty-two commanders for promotion so the grades of rear admiral and captain, respectively: President : Admiral Luke bIcNamee, U.S.Navy. Members : Vice Admiral ?rank H. Clark, U.S.Nav. Rear Admiral- Henry V . Butler, U .S Navy. Rear Admiral Thomas T. Craven, U.S.Navy. Rear Admiral Wat T. Cluverius , U S e Navy. Rear Admiral Thomas C. Hcrt, U.S.Navy. Rear Admiral Orin G. Murfin , U .S .PJavy. Rear Admlral Waiton R. Sexton, U.S.Navy. Rear Admiral T?illiam D , Leshy, U. S.Navy, Recorder: Commander Robert R.M. Emmet, U.S.Navy. QUALIFICATIONS FOR PRONIOTICN e The attention of all officers, and especj.ally of those in the junior grades, is invited to the relationshill bctvceen ,the fundamental elements of their profession, 2nd specialization. As a prime requisite, all offi rs of the Line rmst be capsble mariners and. proficient lecders. Supplementary to tiiis, each should acouire proficiency in at least one specialty of the naval profession. The need for speciPliFts has long been recognized. A generation ago Idahan wrote, "Like other professions, the NaF- tends to, and for efficiency requires, specializa- tion l1 Without competent and sufficiently numerous sl?ecialSsts in each of the many specialties, the Navy as a who2.e cannot operate successfully. -

A Newsletter for the Supporters of the Hampton Roads Naval Museum

Volume 4, Issue 1 A Newsletter for the Supporters of the Hampton Roads Naval Museum Students of the Navy's electronics school drill on the parade grounds in front of the Administration Building on the new Naval Operating Base, Hampton Roads in 1920. Behind them, proudly waving a 48-star jack, is USS Electrician, a mock-up battleship that allowed recruits to get hands-on experience with the increasingly complicated warships. 1997 marks the base 's 80th year as home of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. (HRNM photo) orfolk lawyer Theodore Wool Sewells Point, Virginia. The land was Sam, specifically Uncle Sam's Navy. probably had one of the most somewhat developed as it used to be To be fair to Wool, he was not simply Nthankless tasks that a person home to the great Jamestown Exposition. trying swindle the U.S. Government and could ever ask for. As secretary and But, the fair went bankrupt before the American taxpayers into buying a general counsel to the Norfolk-based year was out and owed over $1.5 million thousand acres of useless, barren land. Fidelity Land and Investment (1907 dollars) in loans and outstanding The Navy had long advertised the fact Corporation, it was his to job to find some bonds. Fidelity agreed to purchase the that it wanted and needed a proper way to clear out and dispose ofhundreds land and buildings from the Expo and operating base for its Atlantic Fleet. Up of acres of abandoned land around the Federal bankruptcy court at a to this point, the fleet had to operate from substantial discount. -

Philip Van Horn (PVH) Weems Papers

Philip Van Horn (P. V. H.) Weems Papers Mark Kahn 2019 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Personal Materials, circa 1905-circa 2005................................................ 6 Series 2: Professional Materials, circa 1905-circa 2005.......................................... 9 Series 3: Oversize Materials, circa 1905-circa 2005............................................ 116 Philip Van Horn (P. V. H.) Weems Papers NASM.2012.0052 Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: Philip Van Horn (P. V. H.) Weems Papers Identifier: NASM.2012.0052 Date: circa 1905-circa 2005 Creator: Weems, Philip Van Horn (P. V. H.) Extent: 101.81 -

Feature Cover USS PENNSYLVANIA (BB

Dedicated to the Study of Naval and Maritime Covers Vol. 87 No. 4 April 2020 Whole No. 1037 April 2020 Feature Cover Fom the Editor’s Desk 2 Send for Your Own Covers 2 Out of the Past 3 USS PENNSYLVANIA (BB 38) Calendar of Events 3 Navy News 4 President’s Message 5 The Goat Locker 6 For Beginning Members 8 MILCOPEX News 9 Norfolk Navy News 10 Website Update 11 USCS Chapter News 11 Fleet Problem XVI Censor 12 Reference Collection No. 2 13 Mystery Naval Ship Cancel 14 Computer Vended Postage 17 USS REDFISH (SS 295) 18 Sailors Write Home 20 USS MICHAEL MONSOOR 22 Foreign Navy Covers 24 April’s feature cover shows an item cancelled aboard USS PENNSYLVANIA (BB 38) during the 1935 Fleet Maneuvers in Sales Circuit Treasure 25 the North Pacific. The cancel is a Locy Type 3y reading ("DATE/ CENSOR/ED") in the dial and (1935 IN N.E. / PACIF. USPOD Metal Duplex TRIANGLE) in the killer bars. This cover is one of the Handstamp History Part 3 26 illustrations used in James Moses’ article on Fleet Problem XVI Censorship beginning on Page 12. Auctions 28 Covers for Sale 30 Classified Ads 31 Secretary’s Report 32 Page 2 Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log April 2020 The Universal Ship Cancellation Society, Inc., (APS From the Editor's Desk Affiliate #98), a non-profit, tax exempt corporation, founded in 1932, promotes the study of the history of ships, their postal It is a dangerous world out there these markings and postal documentation of events involving the U.S. -

The Submarine Chaser Training Center Downtown Miami’S International Graduate School of Anti-Submarine Warfare During World War II

The Submarine Chaser Training Center Downtown Miami’s International Graduate School Of Anti-Submarine Warfare During World War II Charles W. Rice Our purpose is like the Concord light. A continuous vigil at sea. Protecting ships front submarines, To keep our country free.1 The British freighter Umtata slowly lumbered north, hugging the Dade Count}’ coast during the humid South Florida night of July 7, 1942. Backlit by the loom of Miami s lights, she made an irresistible target for German Kapitanleutnant Helmut Mohlntann as he squinted through the lens of Unterseeboot-5~l's periscope. W hen the doomed freighter was fixed in its crosshairs, Mohlntann shouted, “Fire!” The sudden vibration of his stealthy death ship was followed by an immediate hissing sound as the E-7 electric eel escaped its firing tube through a swirl of compressed air bubbles. The U-boat skipper and his hydrophone operator carefully timed the torpedo’s run, while the men hopefully waited for the blast sig naling the demise of yet another victim of Admiral Karl Donitz's “Operation Drumbeat.” Within seconds, a tremendous explosion rewarded their hopes as the star-crossed merchant vessel erupted into a huge billowing fireball.- Millions of gallons of crude oil. gasoline and other petroleum prod ucts desperately needed in the Allied war effort were being shipped up the Florida coast in tankers from Texas, Venezuela, Aruba and Curacao to New Jersey and New York ports. From those staging areas, tankers and freighters carrying oil and munitions combined in convovs traveling east across the North Atlantic to the British Isles. -

Sparks Auctions Sale

SESSION THREE POSTAL HISTORY & LITERATURE FRIDAY, JUNE 26th, 2020 10:00a.m. Lots #1001-1566 Index Lots Canadian Historical Documents 1001-1005 Canada Stampless Covers 1006-1027 Canada - mostly single covers 1028-1081 The Brian Plain Collection of Canadian Dead Letter Offi ces 1082-1120 Canada Airmails 1121-1133 Canada Special Delivery 1134-1136 Canada Postmarks 1137-1158 First Day Covers 1159-1182 B.N.A. 1183-1198 Canada Collections & Accumulations 1199-1270 Military 1271-1316 Commonwealth and Worldwide 1317-1384 The L.V. Pont Collection of Early Air Mail Postal History 1385-1540 Worldwide Airmails 1541-1545 Postcards 1546-1562 Literature 1563-1566 Historical Canadian Documents Canada Stampless Covers 1001 1819 Postmaster Commission Signed by Daniel Suther- land, being a printed form measuring 258 x 400 mm giving nomination to a Mr. McMillan as Postmaster of Grenville, district of Montreal, who is authorized to “keep and retain a commission of twenty per cent”. Dated June 15, 1819, with Sutherland signature next to a large part of a red wax seal. Folds and small faults, still a lovely item and a must have for any serious postal historian. Daniel Sutherland was appoint- ed Postmaster of Montreal in 1807 and also held the offi ce of Military Postmaster during the War of 1812. He replaced 1005 1890, House of Commons Debates Publication (6th Parlia- George Heriot as Postmaster General of Upper and Lower ment, 1890) mailed with a large wrapper showing House of Canada in 1816, and was replaced in 1828 by his son-in Law Commons Free (Davis CH-4i) from P. -

Uss Gearing Dd - 710

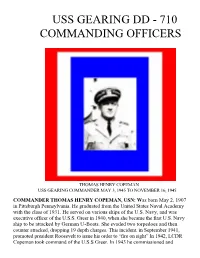

USS GEARING DD - 710 COMMANDING OFFICERS THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN USS GEARING COMMANDER MAY 3, 1945 TO NOVEMBER 16, 1945 COMMANDER THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN, USN: Was born May 2, 1907 in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy with the class of 1931. He served on various ships of the U.S. Navy, and was executive officer of the U.S.S. Greer in 1940, when she became the first U.S. Navy ship to be attacked by German U-Boats. She evaded two torpedoes and then counter attacked, dropping 19 depth charges. This incident, in September 1941, promoted president Roosevelt to issue his order to “fire on sight” In 1942, LCDR Copeman took command of the U.S.S Greer. In 1943 he commissioned and commanded the new Destroyer U.S.S. Brown, and on M ay 3, 1945 he commissioned and commanded the first of a new class of long hull Destroyer, the U.S.S. Gearing DD-710. Commander Copeman commanded the attack cargo ship U.S.S. Ogelethorpe in the Korean Theater of operations. From 1955 to 1956 he was chief staff officer, service force, sixth fleet, his final active duty was that of deputy t chief of staff of the 11 Naval district, He retired in July 1960 as Captain and made his home in Del Mar, California. His decorations included the Silver Star with combat V and the commendation medal with V and Star. Captain Copeman died on December 21, 1982 while hospitalized in San Diego, California. OBITUARY: The San Diego Union Tribune, Sunday 23, 1982 - Capt. -

Uss Gearing Dd - 710 Commanding Officers

USS GEARING DD - 710 COMMANDING OFFICERS THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN USS GEARING COMMANDER MAY 3, 1945 TO NOVEMBER 16, 1945 COMMANDER THOMAS HENRY COPEMAN, USN: Was born May 2, 1907 in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy with the class of 1931. He served on various ships of the U.S. Navy, and was executive officer of the U.S.S. Greer in 1940, when she became the first U.S. Navy ship to be attacked by German U-Boats. She evaded two torpedoes and then counter attacked, dropping 19 depth charges. This incident, in September 1941, promoted president Roosevelt to issue his order to “fire on sight” In 1942, LCDR Copeman took command of the U.S.S Greer. In 1943 he commissioned and commanded the new Destroyer U.S.S. Brown, and on May 3, 1945 he commissioned and commanded the first of a new class of long hull Destroyer, the U.S.S. Gearing DD-710. Commander Copeman commanded the attack cargo ship U.S.S. Ogelethorpe in the Korean Theater of operations. From 1955 to 1956 he was chief staff officer, service force, sixth fleet, his final active duty was that of deputy chief of staff of the 11th Naval district, He retired in July 1960 as Captain and made his home in Del Mar, California. His decorations included the Silver Star with combat V and the commendation medal with V and Star. Captain Copeman died on December 21, 1982 while hospitalized in San Diego, California. OBITUARY: TheSanDiegoUnionTribune, Sunday 23, 1982 - Capt. T. -

Contributed by Wolfgang Hechler Refl.R ADMIRAL EDWIN A

Contributed by Wolfgang Hechler REfl.R ADMIRAL EDWIN A. ANDERSON U. s. NAVY, DECEASED Ec!.w::..n ~l.lexander Anderson was born in W~.lmington, No1... th Carolina, qn July 16, 1860 and was appointed to the Naval Academy, Annapolis, Marylr.ncl., from the Third District of worth Carolina, in June 1878. Graduated -::m J.c.:me 9, lb82, he served. the two years :J.t sea, then re quired by law, and in July 1884 was commissjoned EnEign in the u. s. WS.vy. Through subsequent promotions, he attained. the ranL: of Rear A9-miral in .:rngust 1917, during World War I, and from June 1922 until AµguEt 1923 served in the temporary rank of .LlCJmiral as Commander in Qpief, i'\.siatj_c Fleet. He was retired in his permanent ranlc of Rear 4,!imiral an March 23, 1924, and died on September 23, 1933. 1ifte:i."' ci-,aduatbn from the Naval Academy, he went to sea, as a Pass eel N:i cl.shipman in the USS KEARSARGE, and a year later tronsferrecJ to the USS 2'1LLIANOE. Ee began his commissioned service aboard the 'O~·~ Pii.SSAIC, and during the next four years alEo had duty in the USS :Pf:NSACOJ_._·,, USS KEARSARGE, and USS QUINNEBAUG·,, He was assigned to t:f1e Coast Survey Steamer ENDEAVOR during the period A:prJl 1888 to September 1890, after which he had successtve :::ervtce aboard the USS A:J:.iERT o.ncl USS AlBATR ass. Sho1~e duty at the Branch Hydrographic Office, New orelans, Louj_p :i.c~no., fl"'om January 1894 to May 1895 was followed by a six months 1 rres:1 gnment in the USS MiCH!GAN. -

Mine Warfare Hall of Valor

MINE WARFARE HALL OF VALOR Minesweeping Helicopter Crewmen Explosive Ordnance Disposal Divers Underwater Demolition Team Divers Minesweep Sailors Minelayer Sailors Minemen Navy Cross Medal World War II Korean War Vietnam War Gordon Abbott D’arcy V. Shouldice Cecil H. Martin Dwight Merle Agnew John W. O’Kelley Robert Lee Brock John Richard Cox, Jr. Frank Alfred Davis Thurlow Weed Davison Ross Tompkins Elliott, Jr. Earl W. Ferguson Charles Arthur Ferriter Richard Ellington Hawes William Harold Johnson William Leverette Kabler James Claude Legg Wayne Rowe Loud William Leroy Messmer George R. Mitchell John Henry Morrill Herbert Augustus Peterson George Lincoln Phillips Alfred Humphreys Richards Egbert Adolph Roth William Scheutze Veeder Stephen Noel Tackney Donald C. Taylor John Gardner Tennent, III Peyton Louis Wirtz Silver Star Medal World War II Korean War Vietnam War Henry R. Beausoleil Stephen Morris Archer Larry Gene Aanderud Thomas Edward Chambers Vail P. Carpenter Arnold Roy Ahlbom Wilbur Haines Cheney, Jr. Ernest Carl Castle Edward Joseph Hagl Asa Alan Clark, III Henry E. Davies, Jr. James Edward Hannigan Joe Brice Cochran Don C. DeForest John O. Hood Benjamin Coe Edward P. Flynn, Jr. William D. Jones Ralph W. Cook Robert C. Fuller, Jr. Charles R. Schlegelmilch Nicholas George Cucinello Stanley Platt Gary Richard Lee Schreifels Thurlow Weed Davison Nicholas Grkovic James Louis Foley William D. Haines Edward Lee Foster Bruce M. Hyatt William Handy Hartt, Jr. T. R. Howard James William Haviland, III Philip Levin Robert Messinger Hinckley, Jr. Harry L. Link Charles C. Kirkpatrick Orville W. McCubbin Stanley Leith William Russell McKinney Edgar O. Lesperance Aubrey L.