Spitz Melanoma Is a Distinct Subset of Spitzoid Melanoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deregulated Gene Expression Pathways in Myelodysplastic Syndrome Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Leukemia (2010) 24, 756–764 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/leu ORIGINAL ARTICLE Deregulated gene expression pathways in myelodysplastic syndrome hematopoietic stem cells A Pellagatti1, M Cazzola2, A Giagounidis3, J Perry1, L Malcovati2, MG Della Porta2,MJa¨dersten4, S Killick5, A Verma6, CJ Norbury7, E Hellstro¨m-Lindberg4, JS Wainscoat1 and J Boultwood1 1LRF Molecular Haematology Unit, NDCLS, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK; 2Department of Hematology Oncology, University of Pavia Medical School, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy; 3Medizinische Klinik II, St Johannes Hospital, Duisburg, Germany; 4Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 5Department of Haematology, Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Bournemouth, UK; 6Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA and 7Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK To gain insight into the molecular pathogenesis of the the World Health Organization.6,7 Patients with refractory myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), we performed global gene anemia (RA) with or without ringed sideroblasts, according to expression profiling and pathway analysis on the hemato- poietic stem cells (HSC) of 183 MDS patients as compared with the the French–American–British classification, were subdivided HSC of 17 healthy controls. The most significantly deregulated based on the presence or absence of multilineage dysplasia. In pathways in MDS include interferon signaling, thrombopoietin addition, patients with RA with excess blasts (RAEB) were signaling and the Wnt pathways. Among the most signifi- subdivided into two categories, RAEB1 and RAEB2, based on the cantly deregulated gene pathways in early MDS are immuno- percentage of bone marrow blasts. -

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

A Central Role of IKK2 and TPL2 in JNK Activation and Viral B-Cell Transformation

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14502-x OPEN A central role of IKK2 and TPL2 in JNK activation and viral B-cell transformation Stefanie Voigt1, Kai R. Sterz 1, Fabian Giehler1,2, Anne-Wiebe Mohr 1,2, Joanna B. Wilson 3, Andreas Moosmann 1,2,4 & Arnd Kieser 1,2* IκB kinase 2 (IKK2) is well known for its pivotal role as a mediator of the canonical NF-κB pathway, which has important functions in inflammation and immunity, but also in cancer. 1234567890():,; Here we identify a novel and critical function of IKK2 and its co-factor NEMO in the activation of oncogenic c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling, induced by the latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Independent of its kinase activity, the TGFβ- activated kinase 1 (TAK1) mediates LMP1 signaling complex formation, NEMO ubiquitination and subsequent IKK2 activation. The tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2) kinase is induced by LMP1 via IKK2 and transmits JNK activation signals downstream of IKK2. The IKK2-TPL2-JNK axis is specific for LMP1 and differs from TNFα, Interleukin−1 and CD40 signaling. This pathway mediates essential LMP1 survival signals in EBV-transformed human B cells and post-transplant lymphoma, and thus qualifies as a target for treatment of EBV-induced cancer. 1 Helmholtz Centre Munich - German Research Centre for Environmental Health, Research Unit Gene Vectors, Marchioninistrasse 25, 81377 Munich, Germany. 2 German Centre for Infection Research (DZIF), Partner Site Munich, Munich, Germany. 3 School of Life Sciences, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK. -

Tpl2 (Map3k8) Regulates the Migration, Differentiation, and Function

TPL2 (MAP3K8) REGULATES THE MIGRATION, DIFFERENTIATION, AND FUNCTION OF CRITICAL INNATE IMMUNE CELLS DURING THE INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE by SEAN MICHAEL ROWLEY (Under the Direction of Wendy Watford) ABSTRACT The protein kinase Tpl2 (MAP3K8) regulates innate inflammatory responses and is being actively pursued for therapeutic inhibition during chronic autoimmunity. Herein, we addressed the contribution of Tpl2 to pro-inflammatory responses of NK cells and macrophages. Despite the Tpl2-dependent regulation of IFN secretion by CD4+ T-cells, NK cell IFNγ production, STAT4 expression, and expression of cytotoxic machinery occurred independently of Tpl2. In contrast, tpl2-/- macrophages were functionally defective, as they displayed impaired chemokine and chemokine receptor expression following LPS stimulation and were defective in migrating in vivo to inflamed tissues. Tpl2-/- macrophages were also impaired in their differentiation towards a pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1) while conversely displaying an enhanced anti-inflammatory phenotype (M2). Overall, this work provides additional support for targeting Tpl2, through its effects on macrophage recruitment and differentiation, for the treatment of autoimmunity. INDEX WORDS: autoimmunity, inflammation, cytokines, chemokines, cellular trafficking, NK cells, macrophage classical activation, macrophage alternative activation TPL2 (MAP3K8) REGULATES THE MIGRATION, DIFFERENTIATION, AND FUNCTION OF CRITICAL INNATE IMMUNE CELLS DURING THE INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE by SEAN MICHAEL ROWLEY B.S., University -

Chemokine Expression in the Early Response to Injury in Human Airway Epithelial Cells

RESEARCH ARTICLE Chemokine expression in the early response to injury in human airway epithelial cells Bingqing Xie1,2, Bharathi Laxman3, Somaye Hashemifar1,4, Randi Stern3, T. Conrad Gilliam1, Natalia Maltsev1, Steven R. White3* 1 Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States of America, 2 Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL, United States of America, 3 Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States of America, 4 Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States of America a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Basal airway epithelial cells (AEC) constitute stem/progenitor cells within the central airways and respond to mucosal injury in an ordered sequence of spreading, migration, proliferation, and differentiation to needed cell types. However, dynamic gene transcription in the early OPEN ACCESS events after mucosal injury has not been studied in AEC. We examined gene expression Citation: Xie B, Laxman B, Hashemifar S, Stern R, using microarrays following mechanical injury (MI) in primary human AEC grown in submer- Gilliam TC, Maltsev N, et al. (2018) Chemokine sion culture to generate basal cells and in the air-liquid interface to generate differentiated expression in the early response to injury in human AEC (dAEC) that include goblet and ciliated cells. A select group of ~150 genes was in dif- airway epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0193334. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193334 ferential expression (DE) within 2±24 hr after MI, and enrichment analysis of these genes showed over-representation of functional categories related to inflammatory cytokines and Editor: Hong Wei Chu, National Jewish Health, UNITED STATES chemokines. -

Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/Mtor Cascade Inhibitors: How Mutations Can Result in Therapy Resistance and How to Overcome Resistance

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, October, Vol.3, No 10 Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR Cascade Inhibitors: How Mutations Can Result in Therapy Resistance and How to Overcome Resistance James A. McCubrey1, Linda S. Steelman1, William H. Chappell1, Stephen L. Abrams1, Richard A. Franklin1, Giuseppe Montalto2, Melchiorre Cervello3, Massimo Libra4, Saverio Candido4, Grazia Malaponte4, Maria C. Mazzarino4, Paolo Fagone4, Ferdinando Nicoletti4, Jörg Bäsecke5, Sanja Mijatovic6, Danijela Maksimovic- Ivanic6, Michele Milella7, Agostino Tafuri8, Francesca Chiarini9, Camilla Evangelisti9, Lucio Cocco10, Alberto M. Martelli9,10 1 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA 2 Department of Internal Medicine and Specialties, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy 3 Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Biomedicina e Immunologia Molecolare “Alberto Monroy”, Palermo, Italy 4 Department of Bio-Medical Sciences, University of Catania, Catania, Italy 5 Department of Medicine, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany 6 Department of Immunology, Instititue for Biological Research “Sinisa Stankovic”, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia 7 Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, Italy 8 Sapienza, University of Rome, Department of Cellular Biotechnology and Hematology, Rome, Italy 9 Institute of Molecular Genetics, National Research Council-Rizzoli Orthopedic Institute, Bologna, Italy. 10 Department of Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy Correspondence to: James A. McCubrey, email: [email protected] Keywords: Targeted Therapy, Therapy Resistance, Cancer Stem Cells, Raf, Akt, PI3K, mTOR Received: September 12, 2012, Accepted: October 18, 2012, Published: October 20, 2012 Copyright: © McCubrey et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association Between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic Asthma Ayoung Jeong 1,2, Medea Imboden 1,2, Akram Ghantous 3, Alexei Novoloaca 3, Anne-Elie Carsin 4,5,6, Manolis Kogevinas 4,5,6, Christian Schindler 1,2, Gianfranco Lovison 7, Zdenko Herceg 3, Cyrille Cuenin 3, Roel Vermeulen 8, Deborah Jarvis 9, André F. S. Amaral 9, Florian Kronenberg 10, Paolo Vineis 11,12 and Nicole Probst-Hensch 1,2,* 1 Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, 4051 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Department of Public Health, University of Basel, 4001 Basel, Switzerland 3 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 69372 Lyon, France; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (Z.H.); [email protected] (C.C.) 4 ISGlobal, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (A.-E.C.); [email protected] (M.K.) 5 Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08002 Barcelona, Spain 6 CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), 08005 Barcelona, Spain 7 Department of Economics, Business and Statistics, University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 8 Environmental Epidemiology Division, Utrecht University, Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, 3584CM Utrecht, Netherlands; [email protected] 9 Population Health and Occupational Disease, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, SW3 6LR London, UK; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.F.S.A.) 10 Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Medical University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 11 MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, W2 1PG London, UK; [email protected] 12 Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine (IIGM), 10126 Turin, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-284-8378 Int. -

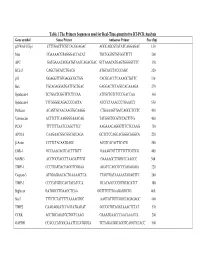

Table 1 the Primers Sequences Used for Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

Table 1 The Primers Sequences used for Real-Time quantitative RT-PCR Analysis Gene symbol Sense Primer Antisense Primer Size (bp) p21WAF1/Cip1 CTTTGACTTCGTCACGGAGAC AGGCAGCGTATATCAGGAGAC 150 Max CGAAAACGTAGGGACCACAT TGCTGGTGTGTGGTTTTT 200 APC GATGAAATAGGATGTAATCAGACGAC GCTAAACATGAGTGGGGTCTC 350 BCL-2 CAGCTGCACCTGACG ATGCACCTACCCAGC 320 p53 GGAGGTTGTGAGGCGCTGG CACGCACCTCAAAGCTGTTC 330 Bax TGCAGAGGATGATTGCTGAC GAGGACTCCAGCCACAAAGA 270 Syndecan-1 TCTGACTCGGTTTCTCCAA ATTGCTGTCTCCCGACCAA 360 Syndecan-3 TTTGGGGCAGACCCCACTA ATCCCTAAACCCTGAACCT 550 Perlecan ACAGTGCAACAAGTGCAAGG CTGAAAGTGACCAGGCTCCTC 450 Vitronectin ACTTCTTCAAGGGGAAACAG TATGGCTGCGTCCACTTTG 400 PCAF TTTTTTTAATCCAGCTTCC AAGAAACAGGGTTTCTCCAAG 750 APO1A CAAGAACGGCGGCGCCAGA GCTCTCCAGCACGGGCAGGCA 220 β-Actin CCTTCTACAATGAGC ACGTCACACTTCATG 260 EGR-1 GCCAAACAGTCACTTTGTT GAAAGTGTTTTTTCTTCGTCG 400 MAPK3 ACCTGCGACCTTAAGATTTGT GAAAAGCTTGGCCCAAGCC 300 TIMP-1 CCCTGATGACGAGGTCGGAA AGATCCAGCGCCCAGAGAGA 220 Caspase-3 ATGGAGAACACTGAAAACTCA TTAGTGATAAAAATAGAGTTC 200 TIMP-3 CCCCATGTGCAGTACATCCA GCACAGCCCCGTGTACATCT 180 Biglycan GATGGCCTGAAGCTCAA GGTTTGTTGAAGAGGCTG 460 Stat3 TTTCTCTATTTTTAAAAGTGC AAGTATTGTCGGCCAGAGAGC 460 TIMP2 CAAGAGGATCCAGTATGAGAT GCCCGTGTAGATAAACTCTAT 570 CCRK ACCTGCAGATGCTGCTCAAG GAAATGAACCCAACAAACCA 200 GAPDH CCACCCATGGCAAATTCCATGGGA TCTAGACGGCAGGTCAGGTCCACC 500 Table 2. Genes with Altered Expression in Cleaved vs. Native Antithrombin-Treated HUVECs Gene Fold Changes Gene Symbol Gene Description Cluster ID (ATC/ATN) Adhesion/ECM ARGN Agrin Hs.273330 2.18 CDH24 Caderhrin-like -

A Novel Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Inhibitor Optimized for Acute

Published OnlineFirst May 9, 2016; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0566 Small Molecule Therapeutics Molecular Cancer Therapeutics A Novel Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Inhibitor Optimized for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Differentiation Activity Sophia Hu1, Masumi Ueda2, Lindsay Stetson1, James Ignatz-Hoover1, Stephen Moreton1, Amit Chakrabarti3, Zhiqiang Xia3, Goutam Karan3, Marcos de Lima2, Mukesh K. Agrawal3,4, and David N. Wald1,3,5 Abstract Standard therapies used for the treatment of acute myeloid describe the discovery of a novel GSK3 inhibitor, GS87. GS87 leukemia (AML) are cytotoxic agents that target rapidly prolifer- was discovered in efforts to optimize GSK3 inhibition for AML ating cells. Unfortunately, this therapeutic approach has differentiation activity. Despite GS87's dramatic ability to induce limited efficacy and significant toxicity and the majority of AML AML differentiation, kinase profiling reveals its high specificity patients still die of their disease. In contrast to the poor prognosis in targeting GSK3 as compared with other kinases. GS87 demon- of most AML patients, most individuals with a rare subtype of strates high efficacy in a mouse AML model system and unlike AML, acute promyelocytic leukemia, can be cured by differenti- current AML therapeutics, exhibits little effect on normal bone ation therapy using regimens containing all-trans retinoic acid. marrow cells. GS87 induces potent differentiation by more GSK3 has been previously identified as a therapeutic target in effectively activating GSK3-dependent signaling components AML where its inhibition can lead to the differentiation and including MAPK signaling as compared with other GSK3 growth arrest of leukemic cells. Unfortunately, existing GSK3 inhibitors. GS87 is a novel GSK3 inhibitor with therapeutic inhibitors lead to suboptimal differentiation activity making potential as a differentiation agent for non-promyelocytic AML. -

Advances in Protein Kinases

ADVANCES IN PROTEIN KINASES Edited by Gabriela Da Silva Xavier Advances in Protein Kinases Edited by Gabriela Da Silva Xavier Published by InTech Janeza Trdine 9, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia Copyright © 2012 InTech All chapters are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. After this work has been published by InTech, authors have the right to republish it, in whole or part, in any publication of which they are the author, and to make other personal use of the work. Any republication, referencing or personal use of the work must explicitly identify the original source. As for readers, this license allows users to download, copy and build upon published chapters even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. Notice Statements and opinions expressed in the chapters are these of the individual contributors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of information contained in the published chapters. The publisher assumes no responsibility for any damage or injury to persons or property arising out of the use of any materials, instructions, methods or ideas contained in the book. Publishing Process Manager Romina Skomersic Technical Editor Teodora Smiljanic Cover Designer InTech Design Team First published June, 2012 Printed in Croatia A free online edition of this book is available at www.intechopen.com Additional hard copies can be obtained from [email protected] Advances in Protein Kinases, Edited by Gabriela Da Silva Xavier p. -

Targeting the Hsp90-Cdc37-Client Protein Interaction to Disrupt Hsp90 Chaperone Machinery Ting Li1, Hu-Lin Jiang2, Yun-Guang Tong3,4 and Jin-Jian Lu1*

Li et al. Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2018) 11:59 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-018-0602-8 REVIEW Open Access Targeting the Hsp90-Cdc37-client protein interaction to disrupt Hsp90 chaperone machinery Ting Li1, Hu-Lin Jiang2, Yun-Guang Tong3,4 and Jin-Jian Lu1* Abstract Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a critical molecular chaperone protein that regulates the folding, maturation, and stability of a wide variety of proteins. In recent years, the development of Hsp90-directed inhibitors has grown rapidly, and many of these inhibitors have entered clinical trials. In parallel, the functional dissection of the Hsp90 chaperone machinery has highlighted the activity disruption of Hsp90 co-chaperone as a potential target. With the roles of Hsp90 co-chaperones being elucidated, cell division cycle 37 (Cdc37), a ubiquitous co-chaperone of Hsp90 that directs the selective client proteins into the Hsp90 chaperone cycle, shows great promise. Moreover, the Hsp90-Cdc37-client interaction contributes to the regulation of cellular response and cellular growth and is more essential to tumor tissues than normal tissues. Herein, we discuss the current understanding of the clients of Hsp90-Cdc37, the interaction of Hsp90-Cdc37-client protein, and the therapeutic possibilities of targeting Hsp90-Cdc37-client protein interaction as a strategy to inhibit Hsp90 chaperone machinery to present new insights on alternative ways of inhibiting Hsp90 chaperone machinery. Keywords: Hsp90 chaperone machinery, Cdc37, Kinase client, Protein interaction Background chloroplast HSP90C, mitochondrial TNFR-associated protein, Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a critically conserved and bacterial high-temperature protein G [2, 8]. In this protein and one of the major molecular chaperones within review,weusethetermHsp90torefertotheseHsp90 eukaryotic cells [1]. -

MAP3K8/TPL-2/COT Is a Potential Predictive Marker for MEK Inhibitor Treatment in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinomas

ARTICLE Received 25 Jun 2015 | Accepted 7 Sep 2015 | Published 12 Oct 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9583 OPEN MAP3K8/TPL-2/COT is a potential predictive marker for MEK inhibitor treatment in high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas Tina Gruosso1,2, Camille Garnier1,2, Sophie Abelanet1,2, Yann Kieffer1,2, Vincent Lemesre1,2, Dorine Bellanger2,3, Ivan Bieche4, Elisabetta Marangoni5, Xavier Sastre-Garau6, Virginie Mieulet1,2,* & Fatima Mechta-Grigoriou1,2,* Ovarian cancer is a silent disease with a poor prognosis that urgently requires new therapeutic strategies. In low-grade ovarian tumours, mutations in the MAP3K BRAF gene constitutively activate the downstream kinase MEK. Here we demonstrate that an additional MAP3K, MAP3K8 (TPL-2/COT), accumulates in high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas (HGSCs) and is a potential prognostic marker for these tumours. By combining analyses on HGSC patient cohorts, ovarian cancer cells and patient-derived xenografts, we demonstrate that MAP3K8 controls cancer cell proliferation and migration by regulating key players in G1/S transition and adhesion dynamics. In addition, we show that the MEK pathway is the main pathway involved in mediating MAP3K8 function, and that MAP3K8 exhibits a reliable predictive value for the effectiveness of MEK inhibitor treatment. Our data highlight key roles for MAP3K8 in HGSC and indicate that MEK inhibitors could be a useful treatment strategy, in combination with conventional chemotherapy, for this disease. 1 Stress and Cancer Laboratory, Institut Curie, 26, rue d’Ulm, Paris 75248, France. 2 Inserm, Genetics and Biology of Cancers, U830, Paris F-75248, France. 3 Genomics and Biology of the Hereditary Breast Cancers, Institut Curie, 26, rue d’Ulm, Paris 75248, France.