Cbnvol8no3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer Domesticus

46 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 46--47 Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer domesticus NEIL SHELLEY 16 Birdrock Avenue, Mount Martha, Victoria 3934 (Email: [email protected]) Summary This note describes an incidental observation of House Sparrows Passer domesticus foraging for insects trapped within the engine bay of motor vehicles in south-eastern Australia. Introduction The House Sparrow Passer domesticus is commensal with man and its global range has increased significantly recently, closely following human settlement on most continents and many islands (Long 1981, Cramp 1994). It is native to Eurasia and northern Africa (Cramp 1994) and was introduced to Australia in the mid 19th century (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999). It is now common in cities and towns throughout eastern Australia (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999, Barrett et al. 2003), particularly in association with human habitation (Schodde & Tidemann 1997), but is decreasing nationally (Barrett et al. 2003). Observation On 13 January 2003 at c. 1745 h Eastern Summer Time, a small group of House Sparrows was observed foraging in the street outside a restaurant in Port Fairy, on the south-western coast of Victoria (38°23' S, 142°14' E). Several motor vehicles were angle-parked in the street, nose to the kerb, adjacent to the restaurant. The restaurant had a few tables and chairs on the footpath for outside dining. The Sparrows appeared to be foraging only for food scraps, when one of them entered the front of a parked vehicle and emerged shortly after with an insect, which it then consumed. -

ISPL-Insight-Aussie-Backyard-Bird-Count

Integrate Sustainability 18 October 2019 Environment Unique Birds of Australia: The Aussie Backyard Bird Count Samantha Mickan – Environmental Specialist It’s that time of year again, time for the Aussie Backyard Bird Count (Backyard Bird Count). Now in its 6th year, the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is occurring between 21st till the 27th of October and is facilitated by Birdlife Australia. Over the course the week participants are encouraged to observe birds around them for 20 minutes using the Aussie Backyard Bird Count app. What is cool is you don’t have to stay in your backyard, you can visit your local pack, nature reserve or head to the beach. Who can’t find 20 minutes, to stop and observe bird occurring in your local area? Who is BirdLife Australia? Birdlife Australia is the largest, independent, non-profit bird conservation organisation in Australia. They run the Backyard Bird Count each year to obtain valuable data on bird communities throughout Australia. The trends extrapolated from this data can be used to get a glimpse into the changes bird populations are undergoing, and subsequently the environment, as Australia’s Unique changes in populations are a reflection of changes in the environment. The count is Birds held in October each year to capture migratory birds which are returning to Australia from the northern hemisphere for nesting, breeding and flocking. Many of these migratory birds are water birds that flock to our coasts where most human populations are situated, making it an ideal time of year for counts. Backyard Bird Count Results 2018 In 2018, 76,918 people in Australia counted 2,751,113 birds over the 7-days period. -

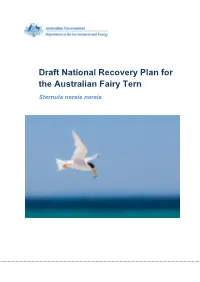

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

LOCAL ACTION PLAN for the COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula

LOCAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula nereis SOUTH AUSTRALIA David Baker-Gabb and Clare Manning Cover Page: Adult Fairy Tern, Coorong National Park. P. Gower 2011 © Local Action Plan for the Coorong Fairy Tern Sternula nereis South Australia David Baker-Gabb1 and Clare Manning2 1 Elanus Pty Ltd, PO BOX 131, St. Andrews VICTORIA 3761, Australia 2 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, PO BOC 314, Goolwa, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5214, Australia Final Local Action Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Baker-Gabb, D., and Manning, C., (2011) Local Action Plan the Coorong fairy tern Sternula nereis, South Australia. Final Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Acknowledgements The authors express thanks to the people who shared their ideas and gave their time and comments. We are particularly grateful to Associate Professor David Paton of the University of Adelaide and to the following staff from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources; Daniel Rogers, Peter Copley, Erin Sautter, Kerri-Ann Bartley, Arkellah Hall, Ben Taylor, Glynn Ricketts and Hafiz Stewart for the care with which they reviewed the original draft. Through the assistance of Lachlan Sutherland, we thank members of the Ngarrindjeri Nation who shared ideas, experiences and observations. Community volunteer wardens have contributed significant time and support in the monitoring of the Coorong fairy tern and the data collected has informed the development of the Plan. The authors gratefully appreciate that your time volunteering must be valued but one can never put a value on that time. Executive Summary The Local Action Plan for the Coorong fairy tern (the Plan) has been written in a way that, with a minimum of revision, may inform a National and State fairy tern Recovery Plan. -

REVIEWS Edited by J

REVIEWS Edited by J. M. Penhallurick BOOKS A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Britain and the World by is consistent in the text (pp 264 - 5) but uses Fleshy-footed Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1978. London: Collins. (a bette~name) in the map (p. 270). Pp xxviii + 292, b. & w. ills.?. 56-, col. pll2 +48, maps 314. 130 x 200 mm. B.25. Parslow does not use scientific names and his English A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Australia and the World by names follow the British custom of dropping the locally Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1980. London: Collins. superfluous adjectives, Thus his names are Leach's Storm- Pp xxviii + 276, b. & w. ills c. 56, col. pll2 + 48, maps 300. Petrel, with a hyphen, and Storm Petrel, without a hyphen; 130 x 200 mm. $A 19.95. and then the Fulmar, the Gannet, the Cormorant, the Shag, A Guide to Seabirds on the Ocean Routes by Gerald Tuck, the Kittiwake and the Puffin. On page 44 we find also 1980. London: Collins. Pp 144, b. & w. ills 58, maps 2. Storm Petrel but elsewhere Hydrobates pelagicus is called 130 x 200 mm. Approx. fi.50. the British Storm-Petrel. A fourth variation in names occurs on page xxv for Comparison of the first two of these books reveals a ridi- seabirds on the danger list of the Red Data Book, where culous discrepancy in price, which is about the only impor- Macgillivray's Petrel is a Pterodroma but on page 44 it is tant difference between them. -

Where Do All the Bush Birds Go?

Australian Bird Count WHERE DO ALL THE BUSH BIRDS GO? In 1989 the RAOU embarked on one of the most ambitious bird counting projects undertaken in Australia – the Australian Bird Count. Now the analysis of the enormous volume of data is beginning to reveal the seasonal movements of our bush birds – including some surprises. by Michael F. Clarke, Peter Griffioen and Richard H. Loyn Supplement to Wingspan, vol. 9, no. 4, December 1999 ¢ ii Australian Bird Count The Australian Bird Count relied on the participation of a dedicated band of volunteers throughout the country. Photo by Jane Miller Inset: The ABC is helping to clarify the seasonal distribution of species that migrate southward from the tropics in summer, such as the Fairy Martin. Photo by Graeme Chapman EVEN A CASUAL OBSERVER KNOWS that the abundance of different bird species changes over time and space. What is less obvious is how changes at individual sites fit in with a continental picture of bird movements. By the early 1980s it was becoming increasingly clear that species and ecosystems could not be properly managed without an understanding of these movements. Thus it was that in the mid-1980s the RAOU’s best method to introduce in Australia.1,2 Four Research Committee decided to embark on an methods were selected for field testing,3 which ambitious Australia-wide project to gather bird showed that active methods (transects or area count data in a consistent and scientific manner. searches) detected more individual birds and species At that time there were already several monitoring in 20 minutes than stationary methods. -

On the Phylogenetic Position of the Scrub-Birds (Passeriformes: Menurae: Atrichornithidae) of Australia

J Ornithol (2007) 148:471^76 DOI 10.1007/S10336-007-0174-9 On the phylogenetic position of the scrub-birds (Passeriformes: Menurae: Atrichornithidae) of Australia R. Terry Chesser • José ten Have Received: 27 July 2006 / Revised: 23 October 2006 / Accepted: 2 March 2007 / Published online: 19 July 2007 © Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2007 Abstract Evolutionary relationships of the scrub-birds Introduction Atrichornis were investigated using complete sequences of the recombination-activating gene RAG-1 and the proto- The Australian endemic family Atrichornithidae consists of oncogene c-mos for two individuals of the noisy scrub-bird two species of small passerine bird: the noisy scrub-bird Atrichornis clamosus. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that Atrichornis clamosus (Gould 1844), an inhabitant of scrub Atrichornis was sister to the genus Menura (the lyrebirds) and dry forest in southwestern Australia, and the rufous and that these two genera (the Menurae) were sister to the scrub-bird A. rufescens (Ramsay 1866), found in subtrop- rest of the oscine passerines. A sister relationship between ical rainforests of eastern Australia. Both are ground- Atrichornis and Menura supports the traditional view, dwelling species of limited distribution, highly secretive based on morphology and DNA hybridization, that these and uncommon within their respective ranges; indeed, taxa are closely related. Similarly, a sister relationship with A. clamosus was considered extinct for many decades prior the remaining oscine passerines agrees with the morpho- to its rediscovery in 1961 (Webster 1962a, b). logical distinctiveness oí Atrichornis and Menura, although John Gilbert, collector of the first specimens of A. this result contradicts conclusions based on DNA hybrid- clamosus, considered the scrub-birds to be similar to the ization studies. -

Birds - First Images of Our Avian Fauna

Birds - first images of our avian fauna J. W. Lewin 1808 May 2019 The Royal Geographical Society of South Australia Mortlock Wing, L2 South State Library of South Australia North Terrace, Adelaide 82077266 [email protected] Birds - first images of our avian fauna P a g e | 2 Our earliest images of birds (and other fauna) were depicted by our Aboriginal communities several millennia before Europeans strode onto the continent. (Nourlangie Rock Art, N.T. circa 15,000 years old) Since European arrival in the late eighteenth century there has been an intense interest in Australia's fauna, particularly birds and particularly among the scientific community of Europe and Northern America who avidly collected bird skins and birds as exotic pets. The range of colourings on the birds and their variety of shapes were so very appealing. Australia and its offshore islands and territories have 898 recorded bird species as of 2014. Of the recorded birds, 165 are considered vagrant or accidental visitors, of the remainder over 45% are classified as Australian endemics: found nowhere else on earth. Australian birds can be classified into six categories: Old endemics: long-established non-passerines of ultimately Gondwanan origin, notably emus, cassowaries and the huge parrot group Corvid radiation: Passerines peculiar to Australasia, descended from the crow family, and now occupying a vast range of roles and sizes; examples include wrens, robins, magpies, thornbills, pardalotes, the huge honeyeater family, treecreepers, lyrebirds, birds-of-paradise and bowerbirds. Eurasian colonists: later colonists from Eurasia, including plovers, swallows, larks, thrushes, cisticolas, sunbirds and some raptor.s Birds - first images of our avian fauna P a g e | 3 Recent introductions: birds recently introduced by humans; some, such as the European goldfinch and greenfinch, appear to coexist with native fauna; others, such as the common starling, blackbird, house and tree sparrows, and the common myna, are more destructive. -

BIRDS of YARRAN DHERAN NATURE RESERVE a Guide For

corridor for birds and other wildlife to the Yarra BIRDS OF YARRAN River at Templestowe. The creek provides a reliable Bird walks are held on a monthly basis in DHERAN NATURE source of water and food sources to birds Yarran Dheran. Come and join us! throughout the whole year and supports our RESERVE permanent residents as well as local nomads, Some successful birdwatching tips seasonal visitors and migratory birds who are -if you have binoculars, learn to focus quickly on a A Guide for birdwatchers passing through. distant object Some birds, like Australian Magpie, Grey Fantail, -to help you in bird identification, visit Rainbow Lorikeet, Tawny Frogmouth and Noisy http://ebird.org/australia or http://birdlife.org.au/ Miners are permanent residents. The ponds provide protected areas for nesting and raising chicks for or use a field guide such as Dusky Moorhens and Pacific Black Ducks. Chestnut -Morcombe, Michael, Field Guide to Australian Teal and Wood Ducks are often seen in the creek. Birds, or Regular visitors over spring and summer include the -Graham Pizzey and Frank Knight, Field Guide to the Olive-backed Oriole and Fan-tailed Cuckoo. Birds of Australia The number of species of birds seen in the Reserve A family of four Tawny Frogmouths Both of these publications are also available as has declined over years, due to loss of habitat and phone apps –invaluable for identifying a bird on the Use this guide as a record of the birds you see at climate factors. spot as they include bird calls as well as showing Yarran Dheran. -

Adele Island Bird Survey Report

Adele Island Bird Survey Report 19th to 24th November 2004 Adrian Boyle PO Box 3089 Broome WA 6725 George Swann PO Box 220 Broome WA 6725 Tim Willing PO Box 2838 Broome WA 6725 Tim Gale PO Box 175 Mareeba Qld 4880 Lisa Collins PO Box 175 Mareeba Qld 4880 Great Knot, One of the most numerous shorebirds recorded during the survey. 1 Contents Introduction Pg 3 Site description Pg 4 Methods Pg 5 Key findings Pg 6 Flag Sightings Pg 7 Conclusion Pg 7 Recommendations Pg 8 Participants on expedition Pg 9 Annotated List of the bird species Pg 10-18 Appendices Appendix A: Map of Adele Island. Pg 19 Appendix B: Shorebird totals plus min/max for national / international importance. Pg20 Appendix C: Tern, Noddy and Gull totals. Pg 21 Appendix D: Shorebird and Tern species with national / international importance. Pg 22 Appendix E: Breeding birds witnessed during survey. Pg 22 Appendix F: CAMBA and JAMBA birds recorded during survey. Pg 23 Appendix G: Tides that occurred during survey. Pg 24 References Pg 25-26 2 Introduction Adele Island lies 150km north of Cape Leveque on Dampier Peninsula Western Australia 15o 31’ S 123o 09’ E. In 2001, Adele Island was transferred from Commonwealth to State tenure and vested as a Class A Nature Reserve (No. 44675) for conservation of Flora and Fauna. It is regarded as a very important seabird nesting island supporting large numbers of birds including the Lesser Frigatebird, Brown Boobies, and Common Noddies. Since 1989, naturalist Kevin Coate (with various associates) has participated in a number of dry season expeditions to the island and published important papers on Adele Islands seabirds (1994, 1995 & 1997). -

Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia R.E

Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia R.E. Johnstone and J.C. Darnell Western Australian Museum, Perth, Western Australia 6000 April 2015 ____________________________________ The area covered by this Western Australian Checklist includes the seas and islands of the adjacent continental shelf, including Ashmore Reef. Refer to a separate Checklist for Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Criterion for inclusion of a species or subspecies on the list is, in most cases, supported by tangible evidence i.e. a museum specimen, an archived or published photograph or detailed description, video tape or sound recording. Amendments to the previous Checklist have been carried out with reference to both global and regional publications/checklists. The prime reference material for global coverage has been the International Ornithological Committee (IOC) World Bird List, The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World, the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volume 1 (Lynx Edicions, Barcelona), A Checklist of the Birds of Britain, 8th edition, the Checklist of North American Birds and, for regional coverage, Zoological Catalogue of Australia volume 37.2 (Columbidae to Coraciidae), The Directory of Australian Birds, Passerines and the Working List of Australian Birds (Birdlife Australia). The advent of molecular investigation into avian taxonomy has required, and still requires, extensive and ongoing revision at all levels – family, generic and specific. This revision to the ‘Checklist of the Birds of Western Australia’ is a collation of the most recent information/research emanating from such studies, together with the inclusion of newly recorded species. As a result of the constant stream of publication of new research in many scientific journals, delays of its incorporation into the prime sources listed above, together with the fact that these are upgraded/re-issued at differing intervals and that their authors may hold varying opinions, these prime references, do on occasion differ. -

Foraging Ecology and Habitat Selection of the Western Yellow

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2003 Foraging Ecology And Habitat Selection Of The Western Yellow Robin (Eopsaltria Griseogularis) In A Wandoo Woodland, Western Australia : Conservation Ecology Of A Declining Species Jarrad A. Cousin Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cousin, J. A. (2003). Foraging Ecology And Habitat Selection Of The Western Yellow Robin (Eopsaltria Griseogularis) In A Wandoo Woodland, Western Australia : Conservation Ecology Of A Declining Species. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1484 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1484 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).