Where Do All the Bush Birds Go?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer Domesticus

46 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 46--47 Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer domesticus NEIL SHELLEY 16 Birdrock Avenue, Mount Martha, Victoria 3934 (Email: [email protected]) Summary This note describes an incidental observation of House Sparrows Passer domesticus foraging for insects trapped within the engine bay of motor vehicles in south-eastern Australia. Introduction The House Sparrow Passer domesticus is commensal with man and its global range has increased significantly recently, closely following human settlement on most continents and many islands (Long 1981, Cramp 1994). It is native to Eurasia and northern Africa (Cramp 1994) and was introduced to Australia in the mid 19th century (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999). It is now common in cities and towns throughout eastern Australia (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999, Barrett et al. 2003), particularly in association with human habitation (Schodde & Tidemann 1997), but is decreasing nationally (Barrett et al. 2003). Observation On 13 January 2003 at c. 1745 h Eastern Summer Time, a small group of House Sparrows was observed foraging in the street outside a restaurant in Port Fairy, on the south-western coast of Victoria (38°23' S, 142°14' E). Several motor vehicles were angle-parked in the street, nose to the kerb, adjacent to the restaurant. The restaurant had a few tables and chairs on the footpath for outside dining. The Sparrows appeared to be foraging only for food scraps, when one of them entered the front of a parked vehicle and emerged shortly after with an insect, which it then consumed. -

Victorian Pardalotes 153 1961

December J CHANDLER, Victorian Pardalotes 153 1961 - evident. Although Jacking the black and gold of the male, the female Regent bird is extremely handsome. On one occasion I watched her and the immature birds feeding on the flowers of a clump of pencil-orchids which were growing on a Satin-ash. Within ten minutes they had stripped every bloom from about 30 or 40 orchids. Another highlight of this year's Noosa holiday was the sighting, again in the company of Barbara and Arthur Salter, of a pair of Beach Stone-curlews ( Orthorhamphus magnirostris) on the island just inside the mouth of the Noosa River. There is little doubt that this would be the pair sighted during the 1958 R .A.O .U. Camp-out and which had their egg washed away by a king-tide. They were again seen in the same place on the island but there was little sign of nesting activity; probably it was too early. Some excellent views of the birds were obtained and the most noticeable points were the large size, the heavy bill, the eye-streak and bar on the wing and the bobbing motion when agitated. When first seen the birds reminded me strongly of a small bustard in gait and general appearance. Since the submission of this paper, advice has been received from Mrs. Essie Green, that a Noisy Pitta in Noosa National Park had been killed by a cat. This bird was probably the " tame" one observed by Mr. Peddie. It is to be hoped that its mate will manage to find another partner, or the Noisy Pitta may indeed disappear from this delightful Park. -

Woodland Birds NE VIC 2018 Online

Woodland Birds of North East Victoria An Identication and Conservation Guide Victoria’s woodlands are renowned for their rich and varied bird life. Unfortunately, one in five woodland bird species in Australia are now threatened. These species are declining due to historical clearing and fragmentation of habitat, lack of habitat Woodland Birds regeneration, competition from aggressive species and predation by cats and foxes. See inside this brochure for ways to help conserve these woodland birds. Victorian Conservation Status of North East Victoria CR Critically Endangered EN Endangered VU Vulnerable NT Near Threatened An Identification and Conservation Guide L Listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (FFG, 1988) * Member of the FFG listed ‘Victorian Temperate Woodland Bird Community’ Peaceful Dove Square-tailed Kite Red-rumped Parrot (male) Red-rumped Parrot (female) Barking Owl Sacred Kingsher Striated Pardalote Spotted Pardalote Size: Approximate length from bill tip to tail tip (cm) Geopelia striata 22 (CT) Lophoictinia isura VU 52 (CT) Psephotus haematonotus 27 (CT) Psephotus haematonotus 27 (CT) Ninox connivens EN L * 41 (CT) Todirhamphus sanctus 21 (CT) Pardalotus striatus 10 (CT) Pardalotus punctatus 10 (CT) Guide to symbols Woodland Birds Woodland Food Source Habitat Nectar and pollen Ground layer Seeds Understorey Fruits and berries Tree trunks Invertebrates Nests in hollows Small prey Canopy Websites: Birdlife Australia www.birdlife.org.au of North East Victoria Birds in Backyards www.birdsinbackyards.net Bush Stone-curlew -

ISPL-Insight-Aussie-Backyard-Bird-Count

Integrate Sustainability 18 October 2019 Environment Unique Birds of Australia: The Aussie Backyard Bird Count Samantha Mickan – Environmental Specialist It’s that time of year again, time for the Aussie Backyard Bird Count (Backyard Bird Count). Now in its 6th year, the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is occurring between 21st till the 27th of October and is facilitated by Birdlife Australia. Over the course the week participants are encouraged to observe birds around them for 20 minutes using the Aussie Backyard Bird Count app. What is cool is you don’t have to stay in your backyard, you can visit your local pack, nature reserve or head to the beach. Who can’t find 20 minutes, to stop and observe bird occurring in your local area? Who is BirdLife Australia? Birdlife Australia is the largest, independent, non-profit bird conservation organisation in Australia. They run the Backyard Bird Count each year to obtain valuable data on bird communities throughout Australia. The trends extrapolated from this data can be used to get a glimpse into the changes bird populations are undergoing, and subsequently the environment, as Australia’s Unique changes in populations are a reflection of changes in the environment. The count is Birds held in October each year to capture migratory birds which are returning to Australia from the northern hemisphere for nesting, breeding and flocking. Many of these migratory birds are water birds that flock to our coasts where most human populations are situated, making it an ideal time of year for counts. Backyard Bird Count Results 2018 In 2018, 76,918 people in Australia counted 2,751,113 birds over the 7-days period. -

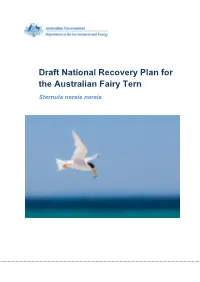

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

The Role of Habitat Variability and Interactions Around Nesting Cavities in Shaping Urban Bird Communities

The role of habitat variability and interactions around nesting cavities in shaping urban bird communities Andrew Munro Rogers BSc, MSc Photo: A. Rogers A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Biological Sciences Andrew Rogers PhD Thesis Thesis Abstract Inter-specific interactions around resources, such as nesting sites, are an important factor by which invasive species impact native communities. As resource availability varies across different environments, competition for resources and invasive species impacts around those resources change. In urban environments, changes in habitat structure and the addition of introduced species has led to significant changes in species composition and abundance, but the extent to which such changes have altered competition over resources is not well understood. Australia’s cities are relatively recent, many of them located in coastal and biodiversity-rich areas, where conservation efforts have the opportunity to benefit many species. Australia hosts a very large diversity of cavity-nesting species, across multiple families of birds and mammals. Of particular interest are cavity-breeding species that have been significantly impacted by the loss of available nesting resources in large, old, hollow- bearing trees. Cavity-breeding species have also been impacted by the addition of cavity- breeding invasive species, increasing the competition for the remaining nesting sites. The results of this additional competition have not been quantified in most cavity breeding communities in Australia. Our understanding of the importance of inter-specific interactions in shaping the outcomes of urbanization and invasion remains very limited across Australian communities. This has led to significant gaps in the understanding of the drivers of inter- specific interactions and how such interactions shape resource use in highly modified environments. -

LOCAL ACTION PLAN for the COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula

LOCAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula nereis SOUTH AUSTRALIA David Baker-Gabb and Clare Manning Cover Page: Adult Fairy Tern, Coorong National Park. P. Gower 2011 © Local Action Plan for the Coorong Fairy Tern Sternula nereis South Australia David Baker-Gabb1 and Clare Manning2 1 Elanus Pty Ltd, PO BOX 131, St. Andrews VICTORIA 3761, Australia 2 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, PO BOC 314, Goolwa, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5214, Australia Final Local Action Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Baker-Gabb, D., and Manning, C., (2011) Local Action Plan the Coorong fairy tern Sternula nereis, South Australia. Final Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Acknowledgements The authors express thanks to the people who shared their ideas and gave their time and comments. We are particularly grateful to Associate Professor David Paton of the University of Adelaide and to the following staff from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources; Daniel Rogers, Peter Copley, Erin Sautter, Kerri-Ann Bartley, Arkellah Hall, Ben Taylor, Glynn Ricketts and Hafiz Stewart for the care with which they reviewed the original draft. Through the assistance of Lachlan Sutherland, we thank members of the Ngarrindjeri Nation who shared ideas, experiences and observations. Community volunteer wardens have contributed significant time and support in the monitoring of the Coorong fairy tern and the data collected has informed the development of the Plan. The authors gratefully appreciate that your time volunteering must be valued but one can never put a value on that time. Executive Summary The Local Action Plan for the Coorong fairy tern (the Plan) has been written in a way that, with a minimum of revision, may inform a National and State fairy tern Recovery Plan. -

Birdquest Australia (Western and Christmas

Chestnut-backed Button-quail in the north was a bonus, showing brilliantly for a long time – unheard of for this family (Andy Jensen) WESTERN AUSTRALIA 5/10 – 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 LEADER: ANDY JENSEN ASSISTANT: STUART PICKERING ! ! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Western Australia (including Christmas Island) 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com Western Shrike-tit was one of the many highlights in the southwest (Andy Jensen) Western Australia, if it were a country, would be the 10th largest in the world! The BirdQuest Western Australia (including Christmas Island) 2017 tour offered an unrivalled opportunity to cover a large portion of this area, as well as the offshore territory of Christmas Island (located closer to Indonesia than mainland Australia). Western Australia is a highly diverse region with a range of habitats. It has been shaped by the isolation caused by the surrounding deserts. This isolation has resulted in a richly diverse fauna, with a high degree of endemism. A must visit for any birder. This tour covered a wide range of the habitats Western Australia has to offer as is possible in three weeks, including the temperate Karri and Wandoo woodlands and mallee of the southwest, the coastal heathlands of the southcoast, dry scrub and extensive uncleared woodlands of the goldfields, coastal plains and mangroves around Broome, and the red-earth savannah habitats and tropical woodland of the Kimberley. The climate varied dramatically Conditions ranged from minus 1c in the Sterling Ranges where we were scraping ice off the windscreen, to nearly 40c in the Kimberley, where it was dust needing to be removed from the windscreen! We were fortunate with the weather – aside from a few minutes of drizzle as we staked out one of the skulkers in the Sterling Ranges, it remained dry the whole time. -

Corymbia Maculata) • Swamp Mahogany (E

Woodland Bird Identification and Survey Methods Workshop Welcome! Woo dlan d Bird Iden tifica tion and Survey MthdMethods WkhWorkshop BirdLife Australia’s Woodland Birds for Biodiversity project The aim of WBfB is to: Enhance the conservation of threatened and declining woodland birds in the temperate region of south-eastern Australia This project funded by: Also doing bird surveys at the tree- planting sites, including some that were planted in 1994 2 Workshop Summary 1. Getting to know woodland birds and their habitat - what are temperate woodlands and ‘woodland birds’? 2. Survey techniques for birds in temperate woodlands - getting started - woodland bird monitoring – the why’s and how’s - Regent Honeyeater habitat and search methods 3. Identification tips for birds in south-eastern Australia’s temperate woodlands - sight recognition - call recognition - useful “clues” - some tricky species - some important species Feel free to ask questions / initiate discussion as we go 3 1. What are temperate woodlands and ‘woodland birds’? What are temperate woodlands? • Woodlands are ecosystems with widely spaced trees (that seldom exceed 30m in height) whose crowns do not overlap • Open forests are often considered woodlands in Australia – and we do for the purposes of categorising “woodland birds” • Characterised by open understorey and sparse ground layer • Mainly on inland slopes of Great Divide / adjacent plains (e.g. Liverpool Plains) and drier, flatter areas in coastal catchments (e.g . Capertee / Hunter Valleys) • Almost all of temperate woodlands in south-east Australia are dominated by eucalypts, occasionally interspersed with native cypress pine, sheoak or buloke 5 Woodlands ain’t woodlands! • Numerous different types of woodlands exist • Most have a dominant species (e.g. -

REVIEWS Edited by J

REVIEWS Edited by J. M. Penhallurick BOOKS A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Britain and the World by is consistent in the text (pp 264 - 5) but uses Fleshy-footed Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1978. London: Collins. (a bette~name) in the map (p. 270). Pp xxviii + 292, b. & w. ills.?. 56-, col. pll2 +48, maps 314. 130 x 200 mm. B.25. Parslow does not use scientific names and his English A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Australia and the World by names follow the British custom of dropping the locally Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1980. London: Collins. superfluous adjectives, Thus his names are Leach's Storm- Pp xxviii + 276, b. & w. ills c. 56, col. pll2 + 48, maps 300. Petrel, with a hyphen, and Storm Petrel, without a hyphen; 130 x 200 mm. $A 19.95. and then the Fulmar, the Gannet, the Cormorant, the Shag, A Guide to Seabirds on the Ocean Routes by Gerald Tuck, the Kittiwake and the Puffin. On page 44 we find also 1980. London: Collins. Pp 144, b. & w. ills 58, maps 2. Storm Petrel but elsewhere Hydrobates pelagicus is called 130 x 200 mm. Approx. fi.50. the British Storm-Petrel. A fourth variation in names occurs on page xxv for Comparison of the first two of these books reveals a ridi- seabirds on the danger list of the Red Data Book, where culous discrepancy in price, which is about the only impor- Macgillivray's Petrel is a Pterodroma but on page 44 it is tant difference between them. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Birdwatching Around Bridgetown Greenbushes

1. Blackwood River Walk Birdwatching in Bridgetown-Greenbushes District An easy 3-4km return walk along the Blackwood Birdwatching River with seating to enjoy the quiet ambience and Bridgetown-Greenbushes District birdlife. Start at the car park at the River Park next The Bridgetown-Greenbushes Shire is a comfortable three hour drive (256km) south of Perth. Bridgetown is nestled to the main bridge and follow the boardwalk across around along the Blackwood River Valley and is surrounded by the river. Turn left for a shorter walk to a creekline attractive rural landscapes and healthy native Forest or right to walk to Gifford Rd and back among Conservation Areas and National Parks. Greenbushes sits Bridgetown Marri and Jarrah trees and views to the river with on the highest point in the area among native forests 15km Melaleuca thickets. Look for waterbirds along the north of Bridgetown. Both towns were settled early and river: Purple Swamphen, Eurasian Coot, Australasian have a long pioneering heritage. Greenbushes and Hoary-headed Grebes and cormorants. Along the track, Western Rosella, Red-capped and Elegant A brochure entitled ‘Your Guide to Walk Trails— Greenbushes-Bridgetown-Hester’ and other information are Parrots, Golden Whistler, Red- available from the Bridgetown Visitor Centre on Hampton eared Firetail, Red-winged and St (Ph: 08 9761 1740). The Greenbushes Discovery Centre Splendid Fairy-wrens, Fan-tailed also has information on the various walk trails around town Cuckoo, Striated Pardalote and (Ph: 08 9764 3883) sometimes Crested Shrike-tit can be found. Western Rosella Acknowledgements Support (male) by the Shire of 2. Rifle Range Rd Bridgetown-Greenbushes Drive about 3km south from the main bridge over the Blackwood River, then turn right into Rifle Range Illustrations / photographs Rd.