Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer Domesticus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Annotated List of Birds Wintering in the Lhasa River Watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China

FORKTAIL 23 (2007): 1–11 An annotated list of birds wintering in the Lhasa river watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China AARON LANG, MARY ANNE BISHOP and ALEC LE SUEUR The occurrence and distribution of birds in the Lhasa river watershed of Tibet Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China, is not well documented. Here we report on recent observations of birds made during the winter season (November–March). Combining these observations with earlier records shows that at least 115 species occur in the Lhasa river watershed and adjacent Yamzho Yumco lake during the winter. Of these, at least 88 species appear to occur regularly and 29 species are represented by only a few observations. We recorded 18 species not previously noted during winter. Three species noted from Lhasa in the 1940s, Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata, Solitary Snipe Gallinago solitaria and Red-rumped Swallow Hirundo daurica, were not observed during our study. Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis (Vulnerable) and Bar-headed Goose Anser indicus are among the more visible species in the agricultural habitats which dominate the valley floors. There is still a great deal to be learned about the winter birds of the region, as evidenced by the number of apparently new records from the last 15 years. INTRODUCTION limited from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. By the late 1980s the first joint ventures with foreign companies were The Lhasa river watershed in Tibet Autonomous Region, initiated and some of the first foreign non-governmental People’s Republic of China, is an important wintering organisations were allowed into Tibet, enabling our own area for a number of migratory and resident bird species. -

ISPL-Insight-Aussie-Backyard-Bird-Count

Integrate Sustainability 18 October 2019 Environment Unique Birds of Australia: The Aussie Backyard Bird Count Samantha Mickan – Environmental Specialist It’s that time of year again, time for the Aussie Backyard Bird Count (Backyard Bird Count). Now in its 6th year, the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is occurring between 21st till the 27th of October and is facilitated by Birdlife Australia. Over the course the week participants are encouraged to observe birds around them for 20 minutes using the Aussie Backyard Bird Count app. What is cool is you don’t have to stay in your backyard, you can visit your local pack, nature reserve or head to the beach. Who can’t find 20 minutes, to stop and observe bird occurring in your local area? Who is BirdLife Australia? Birdlife Australia is the largest, independent, non-profit bird conservation organisation in Australia. They run the Backyard Bird Count each year to obtain valuable data on bird communities throughout Australia. The trends extrapolated from this data can be used to get a glimpse into the changes bird populations are undergoing, and subsequently the environment, as Australia’s Unique changes in populations are a reflection of changes in the environment. The count is Birds held in October each year to capture migratory birds which are returning to Australia from the northern hemisphere for nesting, breeding and flocking. Many of these migratory birds are water birds that flock to our coasts where most human populations are situated, making it an ideal time of year for counts. Backyard Bird Count Results 2018 In 2018, 76,918 people in Australia counted 2,751,113 birds over the 7-days period. -

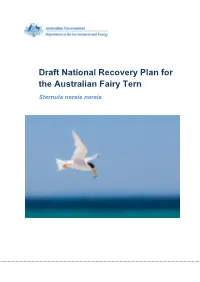

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula Nereis Nereis

Draft National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern Sternula nereis nereis The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Image credit: Adult Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) over Rottnest Island, Western Australia © Georgina Steytler © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. The National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Australian Fairy Tern (Sternula nereis nereis), Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

Correspondence Seen on 31 January 2020, During the Annual Bird Census of Pong Lake (Ranganathan 2020), and Eight on 16 February 2020 (Sharma 2020)

150 Indian BIRDS VOL. 16 NO. 5 (PUBL. 26 NOVEMBER 2020) photographs [142]. At the same place, 15 Sind Sparrows were Correspondence seen on 31 January 2020, during the Annual Bird Census of Pong Lake (Ranganathan 2020), and eight on 16 February 2020 (Sharma 2020). About one and a half kilometers from this place (31.97°N, 75.89°E), I recorded two males and one female Sind The status of the Sind Sparrow Passer pyrrhonotus, Sparrow, feeding on a village road, on 09 March 2020. When Spanish Sparrow P. hispaniolensis, and Eurasian Tree disturbed they took cover in nearby Lantana sp., scrub [143]. Sparrow P. montanus in Himachal Pradesh On 08 August 2020, Piyush Dogra and I were birding on the Five species of Passer sparrows are found in the Indian opposite side of Shah Nehar Barrage Lake (31.94°N, 75.91°E). Subcontinent. These are House Sparrow Passer domesticus, We saw and photographed three Sind Sparrows, sitting on a wire, Spanish Sparrow P. hispaniolensis, Sind Sparrow P. pyrrhonotus, near the reeds. Russet Sparrow P. cinnamomeus, and Eurasian Tree Sparrow P. montanus (Praveen et al. 2020). All of these, except the Sind Sparrow, have been reported from Himachal Pradesh (Anonymous 1869; Grimmett et al. 2011). The Russet Sparrow and the House Sparrow are common residents (den Besten 2004; Dhadwal 2019). In this note, I describe my records of the Sind Sparrow (first for the state) and Spanish Sparrows from Himachal Pradesh. I also compile other records of these three species from Himachal Pradesh. Sind Sparrow Passer pyrrhonotus On 05 February 2017, I visited Sthana village, near Shah Nehar Barrage, Kangra District, Himachal Pradesh, which lies close to C. -

LOCAL ACTION PLAN for the COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula

LOCAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE COORONG FAIRY TERN Sternula nereis SOUTH AUSTRALIA David Baker-Gabb and Clare Manning Cover Page: Adult Fairy Tern, Coorong National Park. P. Gower 2011 © Local Action Plan for the Coorong Fairy Tern Sternula nereis South Australia David Baker-Gabb1 and Clare Manning2 1 Elanus Pty Ltd, PO BOX 131, St. Andrews VICTORIA 3761, Australia 2 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, PO BOC 314, Goolwa, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5214, Australia Final Local Action Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Recommended Citation: Baker-Gabb, D., and Manning, C., (2011) Local Action Plan the Coorong fairy tern Sternula nereis, South Australia. Final Plan for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Acknowledgements The authors express thanks to the people who shared their ideas and gave their time and comments. We are particularly grateful to Associate Professor David Paton of the University of Adelaide and to the following staff from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources; Daniel Rogers, Peter Copley, Erin Sautter, Kerri-Ann Bartley, Arkellah Hall, Ben Taylor, Glynn Ricketts and Hafiz Stewart for the care with which they reviewed the original draft. Through the assistance of Lachlan Sutherland, we thank members of the Ngarrindjeri Nation who shared ideas, experiences and observations. Community volunteer wardens have contributed significant time and support in the monitoring of the Coorong fairy tern and the data collected has informed the development of the Plan. The authors gratefully appreciate that your time volunteering must be valued but one can never put a value on that time. Executive Summary The Local Action Plan for the Coorong fairy tern (the Plan) has been written in a way that, with a minimum of revision, may inform a National and State fairy tern Recovery Plan. -

Insubation Behavior of the Dead Sea Sparrow

340 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS W. Weller for their helpful suggestions in revising JOHNSGARD,P. A., AND J. KEAR. 1968. A review of the manuscript. parental carrying of young by waterfowl. Living Bird 7:89-102. LITERATURE CITED KEAR, J. 1970. The adaptive radiation of paren- tal care in waterfowl, p. 357-392. In J. H. Crook BERGMAN, R. D., AND D. V. DERKSEN. 1977. Ob- Led.], Social behaviour in birds and mammals__I. servations on Arctic and Red-throated Loons at Academic Press, London. Storkersen Point, Alaska. Arctic 30:41-51. KLOPFER. P. H. 1959. The develonment of sotmA-ALU COLLIAS, N. E., A~TII E. C. COLLIAS. 1956. Some signal preferences in ducks. Wilson Bull. 71: mechanisms of family integration in ducks. Auk 262-266. 73 :378-400. LENSINK, C. J. 1967. Arctic Loon predation on GOTTLIED, G. 1965. Imprinting in relation to pa- ducklings. Murrelet 48:41. rental and species identification by avian neo- nates. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 59:345-356. Department of Biology, Queens’ University, Kingston, H~~HN, E. 0. 1972. Arctic Loon breeding in Al- Ontario K7L 3N6, Canada. Accepted for publication berta. Can. Field-Nat. 86:372. 16 February 1978. Condor, 80:340-343 @ The Cooper Ornithological Society 1978 INCUBATION BEHAVIOR OF THE temperatures (Ta) during the incubation period DEAD SEA SPARROW (April-August) can exceed 45°C at noon, and rela- tive humidity (RH) may fall to less than 10% (Ros- nan 1956, Mendelssohn 1974). Their large, covered Y. YOM-TOV nest is generally built on dead branches of tamarisk A. AR trees, and its exterior is totally exposed to solar radia- AND tion. -

The Evolution of Ancestral and Species-Specific Adaptations in Snowfinches at the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

The evolution of ancestral and species-specific adaptations in snowfinches at the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Yanhua Qua,1,2, Chunhai Chenb,1, Xiumin Chena,1, Yan Haoa,c,1, Huishang Shea,c, Mengxia Wanga,c, Per G. P. Ericsond, Haiyan Lina, Tianlong Caia, Gang Songa, Chenxi Jiaa, Chunyan Chena, Hailin Zhangb, Jiang Lib, Liping Liangb, Tianyu Wub, Jinyang Zhaob, Qiang Gaob, Guojie Zhange,f,g,h, Weiwei Zhaia,g, Chi Zhangb,2, Yong E. Zhanga,c,g,i,2, and Fumin Leia,c,g,2 aKey Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100101 Beijing, China; bBGI Genomics, BGI-Shenzhen, 518084 Shenzhen, China; cCollege of Life Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China; dDepartment of Bioinformatics and Genetics, Swedish Museum of Natural History, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden; eBGI-Shenzhen, 518083 Shenzhen, China; fState Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 650223 Kunming, China; gCenter for Excellence in Animal Evolution and Genetics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 650223 Kunming, China; hSection for Ecology and Evolution, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; and iChinese Institute for Brain Research, 102206 Beijing, China Edited by Nils Chr. Stenseth, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, and approved February 24, 2021 (received for review June 16, 2020) Species in a shared environment tend to evolve similar adapta- one of the few avian clades that have experienced an “in situ” tions under the influence of their phylogenetic context. Using radiation in extreme high-elevation environments, i.e., higher snowfinches, a monophyletic group of passerine birds (Passer- than 3,500 m above sea level (m a.s.l.) (17, 18). -

The First Record of Yellow-Throated Sparrow Gymnoris Xanthocollis in Egypt MASSIMILIANO DETTORI & István Moldován

The first record of Yellow-throated Sparrow Gymnoris xanthocollis in Egypt MASSIMILIANO DETTORI & ISTVÁN MOLDOVÁN The Yellow-throated Sparrow Gymnoris xanthocollis breeds in southeast Turkey, through Iraq, Iran, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India (Porter & Aspinall 2010, Rasmussen & Anderton 2005). It has been recorded as a vagrant, three records, in Israel (Perlman & Meyrav 2009). On 5 June 2010, on the Egyptian Red sea coast 17 km north of Marsa Alam city, while birding in the garden of Brayka Bay resort, MD noted a calling Yellow-throated Sparrow in the top of a palm tree (Google Earth GPS coordinates 25° 12’ 59.92” N 34° 47’ 58.23” E). The bird was easily detected as its continuous calling had brought it to the attention of MD. The call was very like that of a House Sparrow Passer domesticus, but because no House Sparrows had been seen or heard in the resort, MD investigated further. During the observation, the bird also uttered a guttural low-tone short song while perched on top of the tree. Through binoculars, the yellow throat-patch, chestnut-coloured feathers on the edge of the scapulars and white median-covert bar were immediately obvious, sufficiently so to identify the bird without any doubt as a Yellow-throated Sparrow. Regarding its behaviour, MD noted that it was very shy, but when its call was imitated by MD, the bird came closer to him and perched on a nearby eucalyptus tree. The bird was observed 07.10–07.30 h before it flew away. Next day (6 June) the bird was seen again at 07.45 h for 10 minutes. -

REVIEWS Edited by J

REVIEWS Edited by J. M. Penhallurick BOOKS A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Britain and the World by is consistent in the text (pp 264 - 5) but uses Fleshy-footed Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1978. London: Collins. (a bette~name) in the map (p. 270). Pp xxviii + 292, b. & w. ills.?. 56-, col. pll2 +48, maps 314. 130 x 200 mm. B.25. Parslow does not use scientific names and his English A Field Guide to the Seabirds of Australia and the World by names follow the British custom of dropping the locally Gerald Tuck and Hermann Heinzel, 1980. London: Collins. superfluous adjectives, Thus his names are Leach's Storm- Pp xxviii + 276, b. & w. ills c. 56, col. pll2 + 48, maps 300. Petrel, with a hyphen, and Storm Petrel, without a hyphen; 130 x 200 mm. $A 19.95. and then the Fulmar, the Gannet, the Cormorant, the Shag, A Guide to Seabirds on the Ocean Routes by Gerald Tuck, the Kittiwake and the Puffin. On page 44 we find also 1980. London: Collins. Pp 144, b. & w. ills 58, maps 2. Storm Petrel but elsewhere Hydrobates pelagicus is called 130 x 200 mm. Approx. fi.50. the British Storm-Petrel. A fourth variation in names occurs on page xxv for Comparison of the first two of these books reveals a ridi- seabirds on the danger list of the Red Data Book, where culous discrepancy in price, which is about the only impor- Macgillivray's Petrel is a Pterodroma but on page 44 it is tant difference between them. -

Passer Domesticus Global Invasive

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Passer domesticus Passer domesticus System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Aves Passeriformes Passeridae Common name gorrion casero (Spanish), town sparrow (English), Europese huismuis (English), house sparrow (English), Gorrion domestico (English, Dominican Republic), moineau domestique (French), house sparrow (English), English sparrow (English) Synonym Similar species Spiza americana, Passer montanus, Passer hispaniolensis Summary Passer domesticus (the house sparrow) is a small bird, native to Eurasia and northern Africa, that was intentionally introduced to the Americas. Passer domesticus are non-migratory birds that are often closely associated with human populations and are found in highest abundance in agricultural, suburban and urban areas. They tend to avoid woodlands, forests, grasslands and deserts. Particularly high densities of Passer domesticus were found where urban settlements meet agricultural areas. They may evict native birds from their nests and out-compete them for trophic resources. Early in its invasion of North America, Passer domesticus began attacking ripening grains on farmland and was considered a serious agricultural pest. Recent surveys indicate populations are declining. view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description The male house sparrow (Passer domesticus) has a brown back with black streaks. The top of the crown is grey, but the sides of the crown and nape are chestnut red. The chin, throat and upper breast are black and the cheeks are white. Females and juveniles are less colourful. They have a grey-brown crown and a light brown or buff eye stripe. The throat, breast and belly are greyish-brown and unstreaked (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2007). Notes North American survey data indicates that the house sparrow (Passer domesticus) populations are declining, particularly in maritime regions and in the eastern and central United States. -

Where Do All the Bush Birds Go?

Australian Bird Count WHERE DO ALL THE BUSH BIRDS GO? In 1989 the RAOU embarked on one of the most ambitious bird counting projects undertaken in Australia – the Australian Bird Count. Now the analysis of the enormous volume of data is beginning to reveal the seasonal movements of our bush birds – including some surprises. by Michael F. Clarke, Peter Griffioen and Richard H. Loyn Supplement to Wingspan, vol. 9, no. 4, December 1999 ¢ ii Australian Bird Count The Australian Bird Count relied on the participation of a dedicated band of volunteers throughout the country. Photo by Jane Miller Inset: The ABC is helping to clarify the seasonal distribution of species that migrate southward from the tropics in summer, such as the Fairy Martin. Photo by Graeme Chapman EVEN A CASUAL OBSERVER KNOWS that the abundance of different bird species changes over time and space. What is less obvious is how changes at individual sites fit in with a continental picture of bird movements. By the early 1980s it was becoming increasingly clear that species and ecosystems could not be properly managed without an understanding of these movements. Thus it was that in the mid-1980s the RAOU’s best method to introduce in Australia.1,2 Four Research Committee decided to embark on an methods were selected for field testing,3 which ambitious Australia-wide project to gather bird showed that active methods (transects or area count data in a consistent and scientific manner. searches) detected more individual birds and species At that time there were already several monitoring in 20 minutes than stationary methods.