Ionizing Radiation—It's Everywhere!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life

Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life Understanding Radioactivity and Radiation in our Everyday Lives Radioactivity is part of our earth – it has existed all along. Naturally occurring radio- active materials are present in the earth’s crust, the floors and walls of our homes, schools, and offices and in the food we eat and drink. Our own bodies- muscles, bones and tissues, contain naturally occurring radioactive elements. Man has always been exposed to natural radiation arising from earth as well as from outside. Most people, upon hearing the word radioactivity, think only about some- thing harmful or even deadly; especially events such as the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, or the Chernobyl Disaster of 1986. However, upon understanding radiation, people will learn to appreciate that radia- tion has peaceful and beneficial applications to our everyday lives. What are atoms? Knowledge of atoms is essential to understanding the origins of radiation, and the impact it could have on the human body and the environment around us. All materi- als in the universe are composed of combination of basic substances called chemical elements. There are 92 different chemical elements in nature. The smallest particles, into which an element can be divided without losing its properties, are called atoms, which are unique to a particular element. An atom consists of two main parts namely a nu- cleus with a circling electron cloud. The nucleus consists of subatomic particles called protons and neutrons. Atoms vary in size from the simple hydro- gen atom, which has one proton and one electron, to large atoms such as uranium, which has 92 pro- tons, 92 electrons. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Glossary Derived From: Human Research Program Integrated Research Plan, Revision A, (January 2009)

Glossary derived from: Human Research Program Integrated Research Plan, Revision A, (January 2009). National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas 77058, pages 232-280. Report No. 153: Information Needed to Make Radiation Protection Recommendations for Space Missions Beyond Low-Earth Orbit (2006). National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, pages 309-318. Reprinted with permission of the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, http://NCRPonline.org . Managing Space Radiation Risk in the New Era of Space Exploration (2008). Committee on the Evaluation of Radiation Shielding for Space Exploration, National Research Council. National Academies Press, pages 111-118. -A- AAPM: American Association of Physicists in Medicine. absolute risk: Expression of excess risk due to exposure as the arithmetic difference between the risk among those exposed and that obtaining in the absence of exposure. absorbed dose (D): Average amount of energy imparted by ionizing particles to a unit mass of irradiated material in a volume sufficiently small to disregard variations in the radiation field but sufficiently large to average over statistical fluctuations in energy deposition, and where energy imparted is the difference between energy entering the volume and energy leaving the volume. The same dose has different consequences depending on the type of radiation delivered. Unit: gray (Gy), equivalent to 1 J/kg. ACE: Advanced Composition Explorer Mission, launched in 1997 and orbiting the L1 libration point to sample energetic particles arriving from the Sun and interstellar and galactic sources. It also provides continuous coverage of solar wind parameters and solar energetic particle intensities (space weather). When reporting space weather, it can provide an advance warning (about one hour) of geomagnetic storms that can overload power grids, disrupt communications on Earth, and present a hazard to astronauts. -

Basics of Radiation Radiation Safety Orientation Open Source Booklet 1 (June 1, 2018)

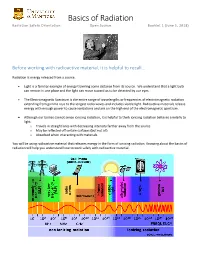

Basics of Radiation Radiation Safety Orientation Open Source Booklet 1 (June 1, 2018) Before working with radioactive material, it is helpful to recall… Radiation is energy released from a source. • Light is a familiar example of energy traveling some distance from its source. We understand that a light bulb can remain in one place and the light can move toward us to be detected by our eyes. • The Electromagnetic Spectrum is the entire range of wavelengths or frequencies of electromagnetic radiation extending from gamma rays to the longest radio waves and includes visible light. Radioactive materials release energy with enough power to cause ionizations and are on the high end of the electromagnetic spectrum. • Although our bodies cannot sense ionizing radiation, it is helpful to think ionizing radiation behaves similarly to light. o Travels in straight lines with decreasing intensity farther away from the source o May be reflected off certain surfaces (but not all) o Absorbed when interacting with materials You will be using radioactive material that releases energy in the form of ionizing radiation. Knowing about the basics of radiation will help you understand how to work safely with radioactive material. What is “ionizing radiation”? • Ionizing radiation is energy with enough power to remove tightly bound electrons from the orbit of an atom, causing the atom to become charged or ionized. • The charged atoms can damage the internal structures of living cells. The material near the charged atom absorbs the energy causing chemical bonds to break. Are all radioactive materials the same? No, not all radioactive materials are the same. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

Cherenkov Radiation

TheThe CherenkovCherenkov effecteffect A charged particle traveling in a dielectric medium with n>1 radiates Cherenkov radiation B Wave front if its velocity is larger than the C phase velocity of light v>c/n or > 1/n (threshold) A β Charged particle The emission is due to an asymmetric polarization of the medium in front and at the rear of the particle, giving rise to a varying electric dipole momentum. dN Some of the particle energy is convertedγ = 491into light. A coherent wave front is dx generated moving at velocity v at an angle Θc If the media is transparent the Cherenkov light can be detected. If the particle is ultra-relativistic β~1 Θc = const and has max value c t AB n 1 cosθc = = = In water Θc = 43˚, in ice 41AC˚ βct βn 37 TheThe CherenkovCherenkov effecteffect The intensity of the Cherenkov radiation (number of photons per unit length of particle path and per unit of wave length) 2 2 2 2 2 Number of photons/L and radiation d N 4π z e 1 2πz 2 = 2 1 − 2 2 = 2 α sin ΘC Wavelength depends on charge dxdλ hcλ n β λ and velocity of particle 2πe2 α = Since the intensity is proportional to hc 1/λ2 short wavelengths dominate dN Using light detectors (photomultipliers)γ = sensitive491 in 400-700 nm for an ideally 100% efficient detector in the visibledx € 2 dNγ λ2 d Nγ 2 2 λ2 dλ 2 2 11 1 22 2 d 2 z sin 2 z sin 490393 zz sinsinΘc photons / cm = ∫ λ = π α ΘC ∫ 2 = π α ΘC 2 −− 2 = α ΘC λ1 λ1 dx dxdλ λ λλ1 λ2 d 2 N d 2 N dλ λ2 d 2 N = = dxdE dxdλ dE 2πhc dxdλ Energy loss is about 104 less hc 2πhc than 2 MeV/cm in water from € -

NATO and NATO-Russia Nuclear Terms and Definitions

NATO/RUSSIA UNCLASSIFIED PART 1 PART 1 Nuclear Terms and Definitions in English APPENDIX 1 NATO and NATO-Russia Nuclear Terms and Definitions APPENDIX 2 Non-NATO Nuclear Terms and Definitions APPENDIX 3 Definitions of Nuclear Forces NATO/RUSSIA UNCLASSIFIED 1-1 2007 NATO/RUSSIA UNCLASSIFIED PART 1 NATO and NATO-Russia Nuclear Terms and Definitions APPENDIX 1 Source References: AAP-6 : NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions AAP-21 : NATO Glossary of NBC Terms and Definitions CP&MT : NATO-Russia Glossary of Contemporary Political and Military Terms A active decontamination alpha particle A nuclear particle emitted by heavy radionuclides in the process of The employment of chemical, biological or mechanical processes decay. Alpha particles have a range of a few centimetres in air and to remove or neutralise chemical, biological or radioactive will not penetrate clothing or the unbroken skin but inhalation or materials. (AAP-21). ingestion will result in an enduring hazard to health (AAP-21). décontamination active активное обеззараживание particule alpha альфа-частицы active material antimissile system Material, such as plutonium and certain isotopes of uranium, The basic armament of missile defence systems, designed to which is capable of supporting a fission chain reaction (AAP-6). destroy ballistic and cruise missiles and their warheads. It includes See also fissile material. antimissile missiles, launchers, automated detection and matière fissile радиоактивное вещество identification, antimissile missile tracking and guidance, and main command posts with a range of computer and communications acute radiation dose equipment. They can be subdivided into short, medium and long- The total ionising radiation dose received at one time and over a range missile defence systems (CP&MT). -

A Study on the Wireless Power Transfer Efficiency of Electrically Small, Perfectly Conducting Electric and Magnetic Dipoles

A study on the wireless power transfer efficiency of electrically small, perfectly conducting electric and magnetic dipoles Article Published Version Open access Moorey, C. L. and Holderbaum, W. (2017) A study on the wireless power transfer efficiency of electrically small, perfectly conducting electric and magnetic dipoles. Progress In Electromagnetics Research C, 77. pp. 111-121. ISSN 1937- 8718 doi: https://doi.org/10.2528/PIERC17062304 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/75906/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2528/PIERC17062304 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2528/PIERC17062304 Publisher: EMW Publishing All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Progress In Electromagnetics Research C, Vol. 77, 111–121, 2017 A Study on the Wireless Power Transfer Efficiency of Electrically Small, Perfectly Conducting Electric and Magnetic Dipoles Charles L. Moorey1 and William Holderbaum2, * Abstract—This paper presents a general theoretical analysis of the Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) efficiency that exists between electrically short, Perfect Electric Conductor (PEC) electric and magnetic dipoles, with particular relevance to near-field applications. The figure of merit for the dipoles is derived in closed-form, and used to study the WPT efficiency as the criteria of interest. -

Power Waveforming: Wireless Power Transfer Beyond Time Reversal

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SIGNAL PROCESSING, VOL. 64, NO. 22, NOVEMBER 15, 2016 5819 Power Waveforming: Wireless Power Transfer Beyond Time Reversal Meng-Lin Ku, Member, IEEE, Yi Han, Hung-Quoc Lai, Member, IEEE, Yan Chen, Senior Member, IEEE,andK.J.RayLiu, Fellow, IEEE Abstract—This paper explores the idea of time-reversal (TR) services [1]. In particular, such an embarrassment is unavoid- technology in wireless power transfer to propose a new wireless able when wireless devices are untethered to a power grid and power transfer paradigm termed power waveforming (PW), where can only be supplied by batteries with limited capacity [2]. In a transmitter engages in delivering wireless power to an intended order to prolong the network lifetime, one immediate solution receiver by fully utilizing all the available multipaths that serve is to frequently replace batteries before the battery is exhausted, as virtual antennas. Two power transfer-oriented waveforms, en- ergy waveform and single-tone waveform, are proposed for PW but unfortunately, this strategy is inconvenient, costly and dan- power transfer systems, both of which are no longer TR in essence. gerous for some emerging wireless applications, e.g., sensor The former is designed to maximize the received power, while the networks in monitoring toxic substance. latter is a low-complexity alternative with small or even no perfor- Recently, energy harvesting has attracted a lot of attention in mance degradation. We theoretically analyze the power transfer realizing self-sustainable wireless communications with perpet- gain of the proposed power transfer system over the direct trans- ual power supplies [3], [4]. Being equipped with a rechargeable mission scheme, which can achieve about 6 dB gain, under various battery, a wireless device is solely powered by the scavenged en- channel power delay profiles and show that the PW is an ideal ergy from the natural environment such as solar, wind, motion, paradigm for wireless power transfer because of its inherent abil- vibration and radio waves. -

Sources, Effects and Risks of Ionizing Radiation

SOURCES, EFFECTS AND RISKS OF IONIZING RADIATION United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation UNSCEAR 2016 Report to the General Assembly, with Scientific Annexes UNITED NATIONS New York, 2017 NOTE The report of the Committee without its annexes appears as Official Records of the General Assembly, Seventy-first Session, Supplement No. 46 and corrigendum (A/71/46 and Corr.1). The report reproduced here includes the corrections of the corrigendum. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The country names used in this document are, in most cases, those that were in use at the time the data were collected or the text prepared. In other cases, however, the names have been updated, where this was possible and appropriate, to reflect political changes. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.17.IX.1 ISBN: 978-92-1-142316-7 eISBN: 978-92-1-060002-6 © United Nations, January 2017. All rights reserved, worldwide. This publication has not been formally edited. Information on uniform resource locators and links to Internet sites contained in the present publication are provided for the convenience of the reader and are correct at the time of issue. The United Nations takes no responsibility for the continued accuracy of that information or for the content of any external website. -

How Do Radioactive Materials Move Through the Environment to People?

5. How Do Radioactive Materials Move Through the Environment to People? aturally occurring radioactive materials Radionuclides can be removed from the air in Nare present in our environment and in several ways. Particles settle out of the our bodies. We are, therefore, continuously atmosphere if air currents cannot keep them exposed to radiation from radioactive atoms suspended. Rain or snow can also remove (radionuclides). Radionuclides released to them. the environment as a result of human When these particles are removed from the activities add to that exposure. atmosphere, they may land in water, on soil, or Radiation is energy emitted when a on the surfaces of living and non-living things. radionuclide decays. It can affect living tissue The particles may return to the atmosphere by only when the energy is absorbed in that resuspension, which occurs when wind or tissue. Radionuclides can be hazardous to some other natural or human activity living tissue when they are inside an organism generates clouds of dust containing radionu- where radiation released can be immediately clides. absorbed. They may also be hazardous when they are outside of the organism but close ➤ Water enough for some radiation to be absorbed by Radionuclides can come into contact with the tissue. water in several ways. They may be deposited Radionuclides move through the environ- from the air (as described above). They may ment and into the body through many also be released to the water from the ground different pathways. Understanding these through erosion, seepage, or human activities pathways makes it possible to take actions to such as mining or release of radioactive block or avoid exposure to radiation.