Fire Hazards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fireboat Is Needed for Halifax Port

B2 TheChronicle Herald BUSINESS Wednesday,February20, 2019 Counsel appointed to represent Quadriga users ANDREA GUNN millions lost in cash and crypto- creditors have been congregating Airey is among many that pany and the court appointed OTTAWA BUREAU currency when the company’s on online forums, mainly Reddit believe something criminal is at monitor attempted to locate the founder and CEO died suddenly and Twitter. play, and is organizing the protest funds. [email protected] in December. “There are more than 100,000 to bring attention to the need for But some blockchain analysts @notandrea Three teams of lawyers had affected users. They range from an investigation. have reported little evidence of initially made apitch to represent small creditors who are owed Airey said he’s concerned that the cold wallets the company Nova Scotia Supreme Court creditors, but Wood’s decision $100, to others who are owed the court is not sufficiently claims are inaccessible, while Justice Michael Wood has ap- identified the selected council as many millions. Privacy is agreat equipped to deal with such a others have been trying to find pointed two law firms to repres- the best positioned for the job. concern and many users do not highly technical case. evidence of possible criminal ent some 115,000 users owed $250 “Both the local and national wish to be publicly identified in “The judge didn’t even know activity on the blockchain that can million by Canadian cryptocur- firms have extensive insolvency any fashion,” Wood wrote. what Reddit was, let alone the be tied to Quadriga’s wallets — rency exchange QuadrigaCX. -

Meet the Seattle Fire Boat Crew the Seattle Fire Department Has a Special Type of Fire Engine

L to R: Gregory Anderson, Richard Chester, Aaron Hedrick, Richard Rush Meet the Seattle fire boat crew The Seattle Fire Department has a special type of fire engine. This engine is a fire boat named Leschi. The Leschi fire boat does the same things a fire engine does, but on the water. The firefighters who work on the Leschi fire boat help people who are sick or hurt. They also put out fires and rescue people. There are four jobs for firefighters to do on the fire boat. The Pilot drives the boat. The Engineer makes sure the engines keep running. The Officer is in charge. Then there are the Deckhands. Engineer Chester says, “The deckhand is one of the hardest jobs on the fire boat”. The deckhands have to be able to do everyone’s job. Firefighter Anderson is a deckhand on the Leschi Fireboat. He even knows how to dive under water! Firefighter Anderson says, “We have a big job to do. We work together to get the job done.” The whole boat crew works together as a special team. The firefighters who work on the fire boat practice water safety all the time. They have special life jackets that look like bright red coats. Officer Hedrick says, “We wear life jackets any time we are on the boat”. The firefighters who work on the fire boat want kids to know that it is important to be safe around the water. Officer Hedrick says, “Kids should always wear their life jackets on boats.” Fishing for Safety The firefighters are using binoculars and scuba gear to find safe stuff under water. -

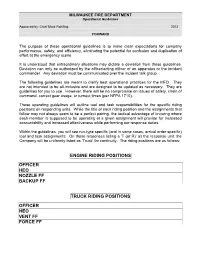

Engine Riding Positions Officer Heo Nozzle Ff

MILWAUKEE FIRE DEPARTMENT Operational Guidelines Approved by: Chief Mark Rohlfing 2012 FORWARD The purpose of these operational guidelines is to make clear expectations for company performance, safety, and efficiency, eliminating the potential for confusion and duplication of effort at the emergency scene. It is understood that extraordinary situations may dictate a deviation from these guidelines. Deviation can only be authorized by the officer/acting officer of an apparatus or the incident commander. Any deviation must be communicated over the incident talk group. The following guidelines are meant to clarify best operational practices for the MFD. They are not intended to be all-inclusive and are designed to be updated as necessary. They are guidelines for you to use. However, there will be no compromise on issues of safety, chain of command, correct gear usage, or turnout times (per NFPA 1710). These operating guidelines will outline tool and task responsibilities for the specific riding positions on responding units. While the title of each riding position and the assignments that follow may not always seem to be a perfect pairing, the tactical advantage of knowing where each member is supposed to be operating at a given assignment will provide for increased accountability and increased effectiveness while performing our response duties. Within the guidelines, you will see run-type specific (and in some cases, arrival order specific) tool and task assignments. On those responses listing a ‘T (or R)’ as the response unit, the Company will be uniformly listed as ‘Truck’ for continuity. The riding positions are as follows: ENGINE RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO NOZZLE FF BACKUP FF TRUCK RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO VENT FF FORCE FF SAFETY If you see something that you believe impacts our safety, it is your duty to report it to your superior Officer immediately. -

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department The Volunteers Early in the nineteenth century Charlotte was a bustling village with all the commercial and manufacturing establishments necessary to sustain an agrarian economy. The census of 1850, the first to enumerate the residents of Charlotte separately from Mecklenburg County, showed the population to be 1,065. Charlotte covered an area of 1.68 square miles and was certainly large enough that bucket brigades were inadequate for fire protection. The first mention of fire services in City records occurs in 1845, when the Board of Aldermen approved payment for repair of a fire engine. That engine was hand drawn, hand pumped, and manned by “Fire Masters” who were paid on an on-call basis. The fire bell hung on the Square at Trade and Tryon. When a fire broke out, the discoverer would run to the Square and ring the bell. Alerted by the ringing bell, the volunteers would assemble at the Square to find out where the fire was, and then run to its location while others would to go the station, located at North Church and West Fifth, to get the apparatus and pull it to the fire. With the nearby railroad, train engineers often spotted fires and used a special signal with steam whistles to alert the community. They were credited with saving many lives and much property. The original volunteers called themselves the Hornets and all their equipment was hand drawn. The Hornet Company purchased a hand pumper in 1866 built by William Jeffers & Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. -

National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Weekend

Remembering Remembering National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Weekend Memorial Firefighters Fallen National 2018 National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Weekend October 6 – 7, 2018 Emmitsburg, Maryland The Fire Hero Family Flag A special American Flag was presented to our Fire Hero Families in October 2014 by the National Honor Guard Commanders Association as a way of honoring the families of firefighters who have paid the supreme sacrifice to their community. The history, tradition, and meaning of the U.S. Flag parallel the significance of our culture and represent the core values of the American Fire Service. As a sign of honor and respect, this flag was requested through the United States Congress in honor of our Fire Hero Families. The flag was flown over the U.S. Capitol on June 14 (Flag Day). The flag then traveled to Emmitsburg, Maryland, and was flown over the National Fallen Firefighters Memorial. The flag then went to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, The Wildland Firefighters Mon- ument in Boise, Idaho, the IAFF Memorial in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and the Department of Defense Firefighters Memorial in San Angelo, Texas. These sites were selected as national representations of the agencies served by our fallen firefighters. This special flag, dedicated to the Fire Hero Family community, also represents the spirit of hope we receive from each other. The bond formed between the families of fallen firefighters and the community of honor guard members can only be described as special. We understand each other without speaking words; we know when a hug is needed without having to ask. We know and appreciate when to flip the switch from humor to seriousness, because we understand and respect each other. -

Building Design for Fire After Earthquake

1569 BUILDING DESIGN FOR FIRE AFTER EARTHQUAKE Russ BOTTING1 And Andy BUCHANAN2 SUMMARY This paper describes a systematic review of fires after major recorded earthquakes throughout the world, reporting ignition sources, fire spread, fire fighting activities, damage to fire protection systems and water supplies. The historical survey is used as a basis for proposed improvements to building design, in order to reduce the impacts of fires in the urban environment after major earthquakes, giving priorities for building owners, territorial authorities and fire services. OVERVIEW Major earthquakes can cause extreme damage to buildings and infrastructure. Earthquakes are largely unpredictable, and large fires following earthquakes are even less predictable. Historical records show that small fires are often initiated by earthquakes, and these sometimes grow into large destructive fires causing loss of life and severe damage to property. The concern is initially with fire damage in individual buildings, where the potential loss of life is much greater in tall buildings than in low-rise buildings. A subsequent concern is with the possibility of devastation resulting from a large urban conflagration. The factors which affect the likelihood of small fires growing into large ones include the amount of earthquake damage, the type and density of building construction, wind conditions, loss of water supplies, and fire fighting capabilities. Control of fires in buildings after earthquakes is only possible if the buildings are designed with good earthquake resistance, good fire protection and good overlap between the two. Even if both are provided separately, the necessary coordination is often missing. Co-ordination between seismic design and fire design includes earthquake resistance of both active and passive fire protection systems, fire protection of items such as seismic gaps, and secure city water supplies. -

Ebook Download American Fireboats: the History of Waterborne

AMERICAN FIREBOATS: THE HISTORY OF WATERBORNE FIREFIGHTING AND RESCUE IN AMERICA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wayne Mutza | 256 pages | 01 Mar 2017 | Schiffer Publishing Ltd | 9780764352713 | English | Atglen, United States American Fireboats: The History of Waterborne Firefighting and Rescue in America PDF Book Jersey City. Two Rolls Royce FF As I have traveled around the country I have attempted to photograph as many of these old and new firefighting and rescue vessels as I can. Tacoma 2. Please try again or alternatively you can contact your chosen shop on or send us an email at. Ocean City. The boats is staffed by personnel at the Airport station who respond over to the boathouse if needed. Other uptight religious Puritans followed them and the whole place became New England. Language: English. It is a culmination of years of study and research into high volume pumping systems and their effects on a small boat's stability, controllability, dynamic loading and righting moments. And so, the thirteen British colonies born of centuries of history and the ideals of their own time made common cause in a complex world and became the United States. The Merchant Marine is composed of all the commercial ships of a country and the personnel that man them. August 20, The ongoing search for fireboats has increased in recent years with some trips specifically designed to locate and photograph a number of boats. Heavy emphasis was placed on accessibility and overall ease of use, and the result is a purpose-built fire fighting machine with next-level capabilities and a crew-friendly layout that firefighters will love. -

1. Fallen Leaf Fire Department

1. FALLEN LEAF FIRE DEPARTMENT 1.1 Demographics, location, topography, and climatic data The Fallen Leaf Fire Department (FLFD) is located in the southwestern portion of the Lake Tahoe Basin (figure 5). The district serves the communities located adjacent to Fallen Leaf Lake on the east and west sides, and the homes located in the Glen Alpine Canyon; an area of approximately 6 square miles. The Departments immediate response area is six square miles with mutual aid responsibilities of about 85 square miles. A summary of land management in the Departments service area is provided in Table 8. Table 8: Land management acreage within the Fallen Leaf Fire Department. Land Administrator Acres State of California 32 LTBMU 3,316 Private/Municipal 298 Total 3,646 Source: TRPA GIS Databases (2004) The area has a permanent year-round population of approximately 50 residents; however the population increases to over 2,000 during peak summer recreational periods. The economy in the area is based primarily on tourism, recreation and vacation home ownership. Daily car visitors, business meetings, seminars, organized summer camp activities, camping, hiking, mountain biking, fishing and summer water sports, bring thousands of tourists from all over the world to the area each year. Elevations within the FLFD range from 6,377 feet above mean sea level at Fallen Leaf Lake to 7,377 feet at the Desolation Wilderness boundary below Cathedral Lake on the west side of the district. The majority of the district is contained inside the bowl created by the medial, lateral and terminal moraines of Angora Ridge, Cathedral Ridge and Taylor Creek meadows. -

The East Bay Hills Fire, Oakland-Berkeley, California

U.S. Fire Administration/Technical Report Series The East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California USFA-TR-060/October 1991 U.S. Fire Administration Fire Investigations Program he U.S. Fire Administration develops reports on selected major fires throughout the country. The fires usually involve multiple deaths or a large loss of property. But the primary criterion T for deciding to do a report is whether it will result in significant “lessons learned.” In some cases these lessons bring to light new knowledge about fire--the effect of building construction or contents, human behavior in fire, etc. In other cases, the lessons are not new but are serious enough to highlight once again, with yet another fire tragedy report. In some cases, special reports are devel- oped to discuss events, drills, or new technologies which are of interest to the fire service. The reports are sent to fire magazines and are distributed at National and Regional fire meetings. The International Association of Fire Chiefs assists the USFA in disseminating the findings throughout the fire service. On a continuing basis the reports are available on request from the USFA; announce- ments of their availability are published widely in fire journals and newsletters. This body of work provides detailed information on the nature of the fire problem for policymakers who must decide on allocations of resources between fire and other pressing problems, and within the fire service to improve codes and code enforcement, training, public fire education, building technology, and other related areas. The Fire Administration, which has no regulatory authority, sends an experienced fire investigator into a community after a major incident only after having conferred with the local fire authorities to insure that the assistance and presence of the USFA would be supportive and would in no way interfere with any review of the incident they are themselves conducting. -

NIOSH Fire Fighter Cancer Study Conducted in Partnership with the National Cancer Institute and the U.S

NIOSH Fire Fighter Cancer Study Conducted in Partnership with the National Cancer Institute and the U.S. Fire Administration Issue 2 Summer 2012 Notes from the (New) Study Director In this Issue: Notes from the Study Greetings from the National Institute for Occupational Director, Doug Daniels Page 1 Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Previous Fire fighter and we work to make your job safer. Studies Page 2 I am the new Study Director for the NIOSH Fire Fighter Cancer Study. Travis Kubale, the previous Study Director, is now the Scientific Program Official for the grant Study Timeline research components of the World Trade Center Health Program. Happily, in this new Page 2 role he will still be involved in addressing health problems of first responders. Spotlight: San Francisco I have been with NIOSH since 2001 and with the Fire Fighter Cancer Study since it Fire Department started in October 2010. We’ve made great progress since then. We have assembled Page 3 most of the data needed for the study from the participating departments and obtained How Will We Estimate information on cancer cases. To date, we are managing records for more than 30,000 Exposure? former and current fire fighters. Once data collection is complete, we will make final Page 4 preparations to perform statistical analyses and publish the results. Frequently Asked In addition to providing you with information about the project, this newsletter Questions features a profile of the San Francisco Fire Department. We plan to profile the other Page 4 two fire departments in upcoming newsletters. -

Sffd | New Fire Boat Station 35 at Pier 22.5

SFFD | NEW FIRE BOAT STATION 35 AT PIER 22.5 MARITIME COMMERCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE – SEPTEMBER 21, 2017 BAYSIDE CONFERENCE ROOM, PIER 1, THE EMBARCADERO, SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94111 AGENDA: • ESER 2014 Background • Site and Project History • Design-Build Procurement • Project Approach Building Design & Construction NEW FIRE BOAT STATION 35 AT PIER 22.5 Project Management Maritime Commerce Advisory Committee | September 21, 2017 1 ESER 2014 BACKGROUND ESER Program Project Map $400M General Obligation Bond authorized in June 2014 with approval by 79% of voters • Neighborhood Fire Stations $85M • Emergency Firefighting Water System $55M • District Police Stations and Infrastructure $30M • Motorcycle Police and Crime Lab $165M • Medical Examiner Facility $65M Building Design & Construction NEW FIRE BOAT STATION 35 AT PIER 22.5 Project Management Maritime Commerce Advisory Committee | September 21, 2017 2 COLLABORATION AMONG CITY DEPARTMENTS Building Design & Construction NEW FIRE BOAT STATION 35 AT PIER 22.5 Project Management Maritime Commerce Advisory Committee | September 21, 2017 3 PARTNERING Partnering Level 3 • External Professional Neutral Facilitator • Kick-off Partnering Workshop • Partnering Charter and Mission Statement • Partnering Sessions • Design Phase • Construction Phase • Executive Group • From senior most levels of City and Design-Builder organizations • Stakeholder Group • Resolution Ladder • Quarterly Project Scorecards • International Partnering Institute Members • San Francisco Public Works • Swinerton Builders • “A Mini -

Fireboat Crew Training Manual 3.5

LONG BEACH FIRE DEPARTMENT FIREBOAT CREW TRAINING MANUAL 3.5 September 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PART 1 – INTRODUCTION History of the Design 4 As-Built Characteristics 5 Training Objectives 6 Training Format 7 MARAD 7 PART 2 – SEAMANSHIP & BOAT HANDLING See Chapman’s 9 PART 3 – SHIP’S SYSTEMS Section I – General Hull Machinery 19 Section II – Furniture & Furnishings 46 Section III – Lifesaving Equipment 49 Section IV – Fire Extinction & Onboard Alarms 51 Section V – Navigating & Electronic Equipment 65 Section VI – HVAC 81 Section VII – Hull Piping Systems 89 Section VIII – Main Propulsion/Controls/Machinery Piping 103 Section IX – Auxiliary Engines & Generators 129 Section X – Power & Lighting 143 Section XI – Firefighting Systems 164 LIST OF FIGURES Folding Stanchion Mooring & Towing Fittings Mast Steering Gear Electrical/Hydraulic Circuit Pilot House Control Console – Steering Control Steering Gear Hydraulic/Mechanical Circuit Flow Paths of 4-Way Directional Control Valve Flow Paths & Steering Cylinder Response Engine Room Fire Suppression System Engine Room Fire Suppression System Main Deck Engine Room Fire Suppression System Engine Room Argus Alarm Panel Halon System Safety Precautions 2 Pilot House Control Console – Navigation HVAC System – Engine Room Supply & Exhaust HVAC System – Heating & Ventilating HVAC System – Miscellaneous Heat & Exhaust Pilot House Control Console – HVAC Bilge System Oily Bilge System Potable Water System Sewage Treatment System Sanitary/Interior Deck Drains Weather Deck Drains Vents & Sounding Tubes