How Can Uganda Benefit from China's Economic Rise?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

Rule by Law: Discriminatory Legislation and Legitimized Abuses in Uganda

RULE BY LAW DIscRImInAtORy legIslAtIOn AnD legItImIzeD Abuses In ugAnDA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 59/06/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Ugandan activists demonstrate in Kampala on 26 February 2014 against the Anti-Pornography Act. © Isaac Kasamani amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction -

Uganda at 50: the Past, the Present and the Future

UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 ii A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue 2012 Published by ACODE P.O. Box 29836, Kampala - UGANDA Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Kabarungi, N. (2013). Uganda at 50: The Past, the Present and the Future. A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue. ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No.17, 2013. Kampala. © ACODE 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is exempted from this restriction. ISBN 978 9970 34 009 5 Cover Photo: A Cross section of participants attending the Uganda @50 in 4 Hours Dialogue held on October 3, 2012 at Sheraton Hotel in Kampala. -

Chased Away and Left to Die

Chased Away and Left to Die How a National Security Approach to Uganda’s National Digital ID Has Led to Wholesale Exclusion of Women and Older Persons ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Publication date: June 8, 2021 Cover photo taken by ISER. An elderly woman having her biometric and biographic details captured by Centenary Bank at a distribution point for the Senior Citizens’ Grant in Kayunga District. Consent was obtained to use this image in our report, advocacy, and associated communications material. Copyright © 2021 by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, and Unwanted Witness. All rights reserved. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice New York University School of Law Wilf Hall, 139 MacDougal Street New York, New York 10012 United States of America This report does not necessarily reflect the views of NYU School of Law. Initiative for Social and Economic Rights Plot 60 Valley Drive, Ministers Village Ntinda – Kampala Post Box: 73646, Kampala, Uganda Unwanted Witness Plot 41, Gaddafi Road Opp Law Development Centre Clock Tower Post Box: 71314, Kampala, Uganda 2 Chased Away and Left to Die ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a joint publication by the Digital Welfare State and Human Rights Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) based at NYU School of Law in New York City, United States of America, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), both based in Kampala, Uganda. The report is based on joint research undertaken between November 2020 and May 2021. Work on the report was made possible thanks to support from Omidyar Network and the Open Society Foundations. -

Presidential Intervention and the Changing 'Politics of Survival' in Kampala's Informal Economy

Tom Goodfellow and Kristof Titeca Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Goodfellow, Tom and Titeca, Kristof (2012) Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy. Cities, 29 (4). pp. 264-270. ISSN 0264-2751 DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.02.004 © 2012 Elsevier This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/39762 Available in LSE Research Online: May 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy Published in Cities: The International -

List of Abbreviations

HRNJ - Uganda Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda) Press Freedom Index Report April 2011 2 HRNJ - Uganda Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Background .............................................................................................. 7 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 7 Elections and Media .............................................................................................. 7 Research Objective ............................................................................................... 8 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 8 Quality check ......................................................................................................... 8 Limitations ............................................................................................................. 9 Part II: Media freedom during national elections in Uganda ................................ 11 Media as a campaign tool ................................................................................... 11 Role of regulatory bodies ................................................................................... 12 Media self censorship ......................................................................................... 14 Censorship of social media -

The Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic and the Health Sector in Uganda

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 3 (2021)pp: 12-19 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper The Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic and the Health Sector in Uganda Nabukeera Madinah (PhD) Senior Lecturer -Islamic University in Uganda Females’ Campus, Faculty of Management Studies Department of Public Administration P.O.Box 7724 Kampala ABSTRACT The cases of Coronavirus disease are on the raise in Uganda, to make matters worse there is increased community transmission of the COVID-19 this increases the spread of the disease since there is carelessness within community members in reference to implementation of standard operating procedures. This paper aimed at investing the experiences during COVID-19 in the health sector in Uganda. Specifically, how Uganda health sector managed COVID 19 pandemic, the lessons learnt from COVID-19, challenges encountered in the health sector during COVID -19 and the impact of COVID 19 on the health sector and way forward. The study used secondary data mainly newspapers to answer the objectives of the study. Findings indicate that Government adhered to WHO guidelines, Ministry of Health designed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), designated health centers for handling COVID-19 patients, quarantine centers, government turned to private hospitals to support in the treatment of coronavirus patients, continued updates from WHO, a taskforce on COVID-19, lockdown of the entire country, quarantines, NGOs in health supported Training of Trainers (TOTs), rapidly mobilized the external and domestic resources to finance the response to COVID -19. KEYWORDS; COVID-19, Health sector, Experiences, Lessons, Challenges, Impact, way forward and Uganda. -

Empirical Evaluation of Weak-Form Efficient Market Hypothesis in Ugandan Securities Exchange

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Emenike, Kalu O.; Joseph, Kirabo K. B. Article Empirical evaluation of weak-form efficient market hypothesis in Ugandan securities exchange Journal of Contemporary Economic and Business Issues Provided in Cooperation with: Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Faculty of Economics Suggested Citation: Emenike, Kalu O.; Joseph, Kirabo K. B. (2018) : Empirical evaluation of weak-form efficient market hypothesis in Ugandan securities exchange, Journal of Contemporary Economic and Business Issues, ISSN 1857-9108, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Faculty of Economics, Skopje, Vol. 5, Iss. 1, pp. 35-50 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193483 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

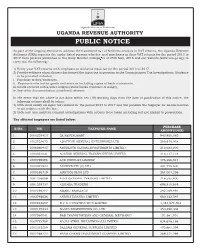

Public Notice

UGANDA REVENUE AUTHORITY PUBLIC NOTICE As part of the ongoing exercise to address the fraudulent use of fi ctitious invoices in VAT returns, the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) requests the under listed persons who declared purchases in their VAT returns for the period 2013 to 2017 from persons published in the Daily Monitor newspaper of 25th May, 2018 and our website (www.ura.go.ug); to carry out the following;- 1) Verify your VAT returns with emphasis on declared input tax for the period 2013 to 2017. 2) Provide evidence of purchases that formed the input tax in question to the Commissioner Tax Investigations. Evidence to be provided includes; i. Purchase orders/contracts, ii. Payments effected for goods and services including copies of bank statements, iii. Goods received notes/store ledgers/stock books (evidence of usage), iv. Any other documentation considered relevant. In the event that the above is not done within ten (10) working days from the date of publication of this notice, the following actions shall be taken; 1) URA shall nullify all input tax claimed for the period 2013 to 2017 and will penalize the taxpayer for misdeclaration in accordance with the law. 2) URA may also institute criminal investigations with actions to be taken including but not limited to prosecution. The affected taxpayers are listed below: PURCHASE S/No. TIN TAXPAYER NAME AMOUNT(UGX) 1. 1000253413 2K RESTAURANT 943,920,085 2. 1002523672 ABATTOIR GENERAL ENTERPRISES LTD 280,679,958 3. 1006860435 ABSOLUTE GLOBAL INVESTMENTS LIMITED 210,682,000 4. 1000021041 ACCESS GENERAL TRANSPORTERS LIMITED 318,117,116 5. -

A Media Minefield RIGHTS Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda WATCH

Uganda HUMAN A Media Minefield RIGHTS Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda WATCH A Media Minefield Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-627-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2010 1-56432-627-6 A Media Minefield Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda I. Map of Uganda ......................................................................................................................... 1 II. Summary ................................................................................................................................. 2 III. Recommendations ................................................................................................................ -

Humanities & Social Sciences

;4 ISSN: 2413-9580 Volume 4 Number 2 November 2015 KIU Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences College of Humanities & Social Sciences, Kampala International University KIU Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences ISSN: 2413-9580 Aims and Scope Information on lecturer and student discounts, single Kampala International University (KIU) Journal of issue rates, local sales representatives, and advertising Humanities and Social Sciences (KJHSS) publishes in the Journal are also available on the site. empirical articles, critical reviews and case studies that Copyright © 2015 Kampala International University are of interest to policy makers, scholars and Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of research or practitioners in the area of humanities and social private study, or criticism or review, and only as sciences. The Journal puts particular focus upon issues permitted under the Copyright Act, this publication that are of concern to the third world. It is the goal of may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any the Journal to advance knowledge and debate in the form or by any means, with the prior written field of social studies by providing a platform through permission of the Publisher. which scholars and practitioners can share their views, findings and experiences. Given the diverse nature of KJHSS is indexed online at www.kiu.ac.ug. social studies, contributions are accepted from a wide Notes for Contributors range of disciplines and preference is given to articles Contributors should adhere to the following that integrate multiple disciplinary perspectives. requirements: Length: 4000 to 6000 words. Format: Contributions that examine developments at national, Times New Roman; size 12 and 1.5 spacing. -

UGANDA Kampala GLT Site Profile

UGANDA Kampala GLT Site Profile AZUSA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY GLOBAL LEARNING TERM 626.857.2753 | www.apu.edu/glt 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO KAMPALA ................................................ 3 GENERAL INFORMATION… ...................................................... 4 CLIMATE AND GEOGRAPHY .................................................... 4 DIET… .......................................................................................... 4 MONEY ........................................................................................ 5 TRANSPORTATION… ................................................................. 5 COMMUNICATION .................................................................... 6 GETTING THERE ....................................................................... 6 VISA ............................................................................................. 7 IMMUNIZATIONS ...................................................................... 7 LANGUAGE LEARNING… ........................................................... 8 HOST FAMILY… ......................................................................... 8 EXCURSIONS .............................................................................. 9 VISITORS .................................................................................... 9 SITE FACILITATOR- GLT UGANDA ........................................ 10 RESOURCES ............................................................................... 12 NOTE: Information is subject to change