'TO GIVE YOU a FUTURE and a HOPE' Kol Nidrey: There Is No Other Moment That Compares to the Enveloping Enchantment of This S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Generation Memories S It Passes Into Middle Age and 1946 Proved Traumatic

VOLUME 16 NO.6 JUNE 2016 journal The Association of Jewish Refugees Second generation memories s it passes into middle age and 1946 proved traumatic. Thereafter, however, Kahlenberg and the Leopoldsberg, to enjoy beyond, every generation looks they took annual holidays in Austrian resorts the spectacular views across Vienna and its back on its own stock of memories, like Kitzbühel and Pörtschach am Wörthersee, surroundings. I learnt that in 1683 the King Asometimes embellished, sometimes of Poland, Jan Sobieski, had launched his diminished, sometimes transmuted and even attack on the Turkish forces besieging Vienna falsified by the passage of time. In this respect, from the Kahlenberg and that much of the the memories of the second generation, the Höhenstraße had been built in the 1930s to children of the Jewish refugees who fled from provide work for the unemployed during the the Nazis, have arguably taken on a special Great Depression; both these topics came quality. Born and brought up in their parents’ across to me as almost equally remote historical countries of refuge – in the case of most of our episodes from a distant past. What relevance readers, Britain – many of them retain links could they have to an English schoolboy? through family memories to aspects of their Only many years later did I realise that I parents’ past in their native lands. had been shown nothing at all relating to our But the Nazi years and the Holocaust personal family history, apart from the family created a gulf between the post-war British firm. Not until I saw my father’s documents present and the pre-war Continental past. -

List of Activities – Inter Faith Week 2018

List of activities – Inter Faith Week 2018 This list contains information about all activities known to have taken place to mark Inter Faith Week 2018 in England, Northern Ireland and Wales. It has been compiled by the Inter Faith Network for the UK, which leads on the Week, based on information it listed on the www.interfaithweek.org website. A short illustrated report on the 2018 Week can be found at https://www.interfaithweek.org/resources/reports The list is ordered alphabetically by town, then within that chronologically by start date. ID: 1631 Date of activity: 19/11/2017 End date: 19/11/2017 Name of activity: Inter Faith Week Discussion and Display Organisation(s) holding the event: Acrrington Library Accrington Youth Group Short description: To mark Inter Faith Week, Accrington Youth Group is using its fortnightly meeting to discuss Inter Faith Week and strengthening inter faith relations, as well as increasing understanding between religious and non‐religious people. Location: St James' St, Accrington, BB5 1NQ Town: Accrington Categories: Youth event ID: 989 Date of activity: 09/11/2017 End date: 09/11/2017 Name of activity: The Alf Keeling Memorial Lecture: Science and Spirituality Organisation(s) holding the event: Altrincham Interfaith Group Short description: Altrincham Interfaith Group is holding the Alf Keeling Memorial Lecture on the theme of 'Science and Spirituality' to mark Inter Faith Week. The lecture will explore how modern scientific discovery relates to ancient Indian philosophy. The lecture will be delivered by Dr Girdari Lal Bhan, Hindu Representative at Greater Manchester Faith Community Leaders Group. Location: St Ambrose Preparatory School Hall, Wicker Town: Altrincham Lane, Hale Barns, WA15 0HE Categories: Conference/seminar/talk/workshop ID: 1632 Date of activity: 13/11/2017 End date: 17/11/2017 Name of activity: All Different, All Equal Organisation(s) holding the event: Audlem St. -

10 WINTER 1986 Ffl Jiiirfuijtjjrii-- the Stemberg Centre for Judaism, the Manor House , 80 East End Road, Contents London N3 2SY Telephone: 01-346 2288

NA NUMBEFt 10 WINTER 1986 ffl jiiirfuijTJJriI-- The Stemberg Centre for Judaism, The Manor House , 80 East End Road, Contents London N3 2SY Telephone: 01-346 2288 2 Jaclynchernett We NowNeeda separate MANNA is the Journal of the Sternberg Conservative Movement Centre for Judaism at the Manor House and of the Manor House Society. 3 MichaelLeigh Andwhywe Mus.tTake upthe challenge MANI`IA is published quarterly. 4 Charlesselengut WhyYoung Jews Defectto cults Editor: Rabbi Tony Bayfield Deputy Editor: Rabbi william Wolff Art Editor: Charles Front 8 LionelBlue lnklings Editorial Assistant: Elizabeth Sarah Curtis cassell Help! Editorial Board: Rabbi Colin Eimer, 10 ^ Deirdreweizmann The outsider Getting Inside Rabbi Dr. Albert Friedlander, Rabbi the Jewish Skin David Goldberg, Dr. Wendy Green- gross, Reverend Dr. Isaac Levy, Rabbi Dr. Jonathan Magonet, Rabbi Dow Mamur, Rabbi Dr. J.ohm Rayner, Pro- 12 LarryTabick MyGrandfather Knew Isaac Bashevis singer fessor J.B . Segal, Isca Wittenberg. 14 Wendy Greengross Let's pretend Views expressed in articles in M¢7!#cz do not necessarily reflect the view of the Editorial Board. 15 JakobJ. Petuchowski The New Machzor. Torah on One Foot Subscription rate: £5 p.a. (four issues) including postage anywhere in the U.K. 17 Books. Lionel Blue: From pantryto pulpit Abroad: Europe - £8; Israel, Asia; Evelyn Rose: Blue's Blender Americas, Australasia -£12. 18 Reuven silverman Theycould Ban Baruch But Not His Truth A 20 Letters 21 DavjdGoldberg Lastword The cover shows Zlfee Jew by Jacob Kramer, an ink on yellow wash, circa 1916, one of many distinguished pic- tures currently on exhibition at the Stemberg Centre. -

Femmes Juives

leREVUE MENSUELLE shofar DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ ISRAÉLITE LIBÉRALE DE BELGIQUE N° d’agréation P401058 DÉCEMBRE 2013 - N°349 / TEVET 5774 SYNAGOGUE BETH HILLEL BRUXELLES FEMMES JUIVES Le Shofar est édité par la COMMUNAUTÉ ISRAÉLITE LIBÉRALE N°349 DÉCEMBRE 2013 DE BELGIQUE A.S.B.L. TEVET 5774 N° d’entreprise : 408.710.191 N° d’agréation P401058 Synagogue Beth Hillel REVUE MENSUELLE DE LA 80, rue des Primeurs COMMUNAUTÉ ISRAÉLITE B-1190 Bruxelles LIBÉRALE DE BELGIQUE Tél. 02 332 25 28 Fax 02 376 72 19 EDITEUR RESPONSABLE : www.beth-hillel.org Gilbert Lederman [email protected] CBC 192-5133742-59 REDACTEUR EN CHEF : IBAN : BE84 1925 1337 4259 Luc Bourgeois BIC : CREGBEBB SECRÉTAIRE DE RÉDACTION : RABBIN : Rabbi Marc Neiger Yardenah Presler RABBIN HONORAIRE : COMITÉ DE RÉDACTION : Rabbi Abraham Dahan Rabbi Marc Neiger, Gilbert Lederman, DIRECTEUR: Luc Bourgeois Isabelle Telerman, Luc Bourgeois PRÉSIDENT HONORAIRE : Ont participé à ce numéro du Shofar : Paul Gérard Ebstein z"l Catherine Danelski-Neiger, Anne De Potter, Leah Pascale CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION : Engelmann, Annie Szwertag, Gaëlle Gilbert Lederman (Président), Myriam Szyffer, David Zilberberg Abraham, Gary Cohen, Anne De Potter, Nathan Estenne, Ephraïm Fischgrund, MISE EN PAGE : Josiane Goldschmidt, Gilbert Leder- inextremis.be man, Willy Pomeranc, Gaëlle Szyffer, Elie Vulfs, Pieter Van Cauwenberge, ILLUSTRATION COUVERTURE : Jacqueline Wiener-Henrion Old Jewish woman, ca. 1880 Meijer de Haan Les textes publiés n’engagent que leurs auteurs. Sommaire EDITORIAL 5 Femmes juives (Luc Bourgeois, -

Reform Judaism: in 1000 Words Gender

Reform Judaism: In 1000 Words Gender Context One of the distinctive features of Reform Judaism is our unequivocal commitment to gender equality. Or is it? As Rabbi Barbara Borts of Darlington Hebrew Congregation writes, though there are many examples of equality in our movement (such as our exceptional siddur and women in senior rabbinic positions) the journey towards true equality in our communities has been a process of development over many years, and in some ways is not yet complete. Content The male rabbi who was approached to write this section demurred, believing it was inappropriate for him to write about gender issues. Gender, he believed, really meant ‘women.’ This is a natural conclusion. After all, Judaism developed as a patriarchal religion with strict delineations between male Jewish life and female Jewish life: male Judaism was the norm [a Jew and His Judaism] and the woman, a separate category.i Although the idea of gender now encompasses many aspects of sexual identity, for most people, ‘gender’ will mean ‘women’ and we will thus examine past and current thinking about women’s roles in the MRJ. In 1840 West London Synagogue, women’s equality was not part of the founders’ visions. Women sat in the balcony until 1910 (except for the Yamim Nora’im) and the choir was initially all-male, although women would join early on.ii Other founding synagogues discussed participation by women, but there was no consensus about what equality for women entailed, not even through the 1990s and perhaps beyond. The first women rabbis often encountered great opposition and found it difficult to gain employment against male candidates for particular jobs. -

Simon Benscher (C

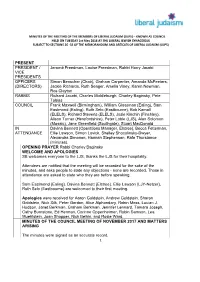

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE MEMBERS OF LIBERAL JUDAISM (ULPS) – KNOWN AS COUNCIL HELD ON TUESDAY 1st May 2018 AT THE LIBERAL JEWISH SYNAGOGUE SUBJECT TO SECTIONS 26 -32 OF THE MEMORANDUM AND ARTICLES OF LIBERAL JUDAISM (ULPS) PRESENT PRESIDENT / Jeromé Freedman, Louise Freedman, Rabbi Harry Jacobi VICE PRESIDENTS OFFICERS Simon Benscher (Chair), Graham Carpenter, Amanda McFeeters, (DIRECTORS) Jackie Richards, Ruth Seager, AmeLia Viney, Karen Newman, Ros CLayton RABBIS Richard Jacobi, CharLes MiddLeburgh, CharLey Baginsky, Pete Tobias COUNCIL Frank MaxweLL (Birmingham), WiLLiam GLassman (EaLing), Sam Eastmond (EaLing), Ruth SeLo (Eastbourne), Bob KamaLL (ELELS), Richard Stevens (ELELS), Josie Kinchin (FinchLey), ALison Turner (Herefordshire), Peter LobLe (LJS), ALan SoLomon (Mosaic), Jane GreenfieLd (Southgate), Stuart MacDonaLd IN Davina Bennett (Operations Manager, ELstree), Becca Fetterman, ATTENDANCE ELLie Lawson, Simon Lovick, SheLLey ShocoLinsky-Dwyer, ALexandra Simonon, Hannah Stephenson, Rafe Thurstance (minutes). OPENING PRAYER Rabbi CharLey Baginsky WELCOME AND APOLOGIES SB weLcomes everyone to the LJS, thanks the LJS for their hospitaLity. Attendees are notified that the meeting wiLL be recorded for the sake of the minutes, and asks peopLe to state any objections - none are recorded. Those in attendance are asked to state who they are before speaking. Sam Eastmond (EaLing), Davina Bennett (ELstree), ELLie Lawson (LJY-Netzer), Ruth SeLo (Eastbourne) are weLcomed to their first meeting. Apologies were received for Aaron GoLdstein, Andrew GoLdstein, Sharon GoLdstein, Nick SiLk, Peter Gordon, ALice ALphandary, Robin Moss, Lucian J. Hudson, Janet Berkman, Graham Berkman, Jennifer Lennard, Tamara Joseph, Cathy Burnstone, Ed Herman, Corinne Oppenheimer, Robin Samson, Lea MuehLstein, Joan Shopper, Nick BeLkin, and Rosie Ward. MINUTES OF THE COUNCIL MEETING OF NOVEMBER 2017 AND MATTERS ARISING The minutes were signed as an accurate record. -

Jewish Philosophy and Western Culture Jewish Prelims I-Xvi NEW.Qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page Ii

Jewish_Prelims_i-xvi NEW.qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page i Jewish Philosophy and Western Culture Jewish_Prelims_i-xvi NEW.qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page ii ‘More than just an introduction to contemporary Jewish philosophy, this important book offers a critique of the embedded assumptions of contemporary post-Christian Western culture. By focusing on the suppressed or denied heritage of Jewish and Islamic philosophy that helped shape Western society, it offers possibilities for recovering broader dimensions beyond a narrow rationalism and materialism. For those impatient with recent one-dimensional dismissals of religion, and surprised by their popularity, it offers a timely reminder of the sources of these views in the Enlightenment, but also the wider humane dimensions of the religious quest that still need to be considered. By recognising the contribution of gender and post-colonial studies it reminds us that philosophy, “the love of wisdom”, is still concerned with the whole human being and the complexity of personal and social relationships.’ Jonathan Magonet, formerly Principal of Leo Baeck College, London, and Vice-President of the Movement for Reform Judaism ‘Jewish Philosophy and Western Culture makes a spirited and highly readable plea for “Jerusalem” over “Athens” – that is, for recovering the moral and spiritual virtues of ancient Judaism within a European and Western intellectual culture that still has a preference for Enlightenment rationalism. Victor Seidler revisits the major Jewish philosophers of the last century as invaluable sources of wisdom for Western philosophers and social theorists in the new century. He calls upon the latter to reclaim body and heart as being inseparable from “mind.”’ Peter Ochs, Edgar Bronfman Professor of Modern Judaic Studies, University of Virginia Jewish_Prelims_i-xvi NEW.qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page iii JEWISH PHILOSOPHY AND WESTERN CULTURE A Modern Introduction VICTOR J. -

Happy Birthday Harry

January/February 2016 VOL. XLIII No. 1 Liberal Judaism is a constituent of the World Union for Progressive Judaism www.liberaljudaism.org ljtoday Happy birthday Harry Mitzvah Day NE OF Liberal Judaism’s most The Liberal Jewish Synagogue (LJS) Award for NPLS beloved, and senior, rabbis service was taken by two of Harry’s Ocelebrated his 90th birthday with children, Rabbis Dr Margaret and Richard special services and kiddushim held at Jacobi, along with LJS senior rabbi, communities all over the UK. Rabbi Alexandra Wright. Harry gave the Rabbi Harry Jacobi was joined by sermon. Others in attendance included friends, family and Liberal Judaism Simon Benscher and Rabbi Danny Rich, members at events at The Liberal Jewish the chair and senior rabbi of Liberal Synagogue, Woodford Liberal Synagogue, Judaism, Rabbi Rachel Benjamin and Birmingham Progressive Synagogue, Rabbi Dr David Goldberg. Southgate Progressive Synagogue, At the end of the service, Harry was Northwood & Pinner Liberal Synagogue visibly moved as his young granddaughter and South Bucks Jewish Community. Tali presented him with a Festschrift Harry, who was born as Heinz Martin written in his honour. The book, reviewed Hirschberg in October 1925, and grew on page 10 of this issue of lj today, was up in Auerbach, Germany, twice fled the edited by Rabbi Danny Rich and features Nazis to become one of Britain’s most contributions from leading Progressive NORTHWOOD & PINNER LIBERAL respected and inspiring religious leaders. Jewish rabbis and thinkers. Another SYNAGOGUE (NPLS) won this year’s granddaughter, Abigail, Mitzvah Day Award for Interfaith wrote the biography Partnership of the Year. -

Leo Baeck College at the HEART of PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM

Leo Baeck College AT THE HEART OF PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM Leo Baeck College Students – Applications Privacy policy February 2021 Leo Baeck College Registered office • The Sternberg Centre for Judaism • 80 East End Road, London, N3 2SY, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 8349 5600 • Email: [email protected] www .lbc.ac.uk Registered in England. Registered Charity No. 209777 • Company Limited by Guarantee. UK Company Registration No. 626693 Leo Baeck College is Sponsored by: Liberal Judaism, Movement for Reform Judaism • Affiliate Member: World Union of Progressive Judaism Leo Baeck College AT THE HEART OF PROGRESSIVE JUDAISM A. What personal data is collected? We collect the following personal data during our application process: • address • phone number • e-mail address • religion • nationality We also require the following; • Two current passport photographs. • Original copies of qualifications and grade transcripts. Please send a certified translation if the documents are not in English. • Proof of English proficiency at level CERF B or International English Language Testing System Level 6 or 6+ for those whose mother tongue is not English or for those who need a Tier 4 (General) visa. • Photocopy of the passport pages containing personal information such as nationality Interviewers • All notes taken at the interview will be returned to the applications team in order to ensure this information is stored securely before being destroyed after the agreed timescale. Offer of placement • We will be required to confirm your identity. B. Do you collect any special category data? We collect the following special category data: • Religious belief C. How do you collect my data from me? We use online application forms and paper application forms. -

Archives of the West London Synagogue

1 MS 140 A2049 Archives of the West London Synagogue 1 Correspondence 1/1 Bella Josephine Barnett Memorial Prize Fund 1959-60 1/2 Blackwell Reform Jewish Congregation 1961-67 1/3 Blessings: correspondence about blessings in the synagogue 1956-60 1/4 Bradford Synagogue 1954-64 1/5 Calendar 1957-61 1/6 Cardiff Synagogue 1955-65 1/7 Choirmaster 1967-8 1/8 Choral society 1958 1/9 Confirmations 1956-60 1/10 Edgeware Reform Synagogue 1953-62 1/11 Edgeware Reform Synagogue 1959-64 1/12 Egerton bequest 1964-5 1/13 Exeter Hebrew Congregation 1958-66 1/14 Flower boxes 1958 1/15 Leo Baeck College Appeal Fund 1968-70 1/16 Leeds Sinai Synagogue 1955-68 1/17 Legal action 1956-8 1/18 Michael Leigh 1958-64 1/19 Lessons, includes reports on classes and holiday lessons 1961-70 1/20 Joint social 1963 1/21 Junior youth group—sports 1967 MS 140 2 A2049 2 Resignations 2/1 Resignations of membership 1959 2/2 Resignations of membership 1960 2/3 Resignations of membership 1961 2/4 Resignations of membership 1962 2/5 Resignations of membership 1963 2/6 Resignations of membership 1964 2/7 Resignations of membership Nov 1979- Dec1980 2/8 Resignations of membership Jan-Apr 1981 2/9 Resignations of membership Jan-May 1983 2/10 Resignations of membership Jun-Dec 1983 2/11 Synagogue laws 20 and 21 1982-3 3 Berkeley group magazines 3/1 Berkeley bulletin 1961, 1964 3/2 Berkeley bulletin 1965 3/3 Berkeley bulletin 1966-7 3/4 Berkeley bulletin 1968 3/5 Berkeley bulletin Jan-Aug 1969 3/6 Berkeley bulletin Sep-Dec 1969 3/7 Berkeley bulletin Jan-Jun 1970 3/8 Berkeley bulletin -

8460 LBC Prospectus New Brand

PROSPECTUS 2016/17 CONTENTS Rabbinic Programme ............................................................................................... 1 Structure Of The Rabbinic Programme ................................................................... 2 Graduate Diploma In Hebrew And Jewish Studies, Part 1 ...................................... 3 Graduate Diploma In Hebrew And Jewish Studies, Part 2 ...................................... 4 Postgraduate Diploma In Hebrew And Jewish Studies ........................................... 5 MA In Applied Rabbinic Theology .......................................................................... 6 Research Degrees: M.Phil, PhD ............................................................................... 7 MA In Jewish Educational Leadership ..................................................................... 8 Certificate of H.E. In Jewish Education ................................................................... 9 Foundation Course For Religion School Teachers................................................. 10 Adult Jewish Learning ........................................................................................... 11 Continual Professional Development .................................................................... 12 Interfaith Programme ............................................................................................ 12 Library And Resources ........................................................................................... 13 Application Process .............................................................................................. -

Women's Torah Text

Index by Author . Foreword: The Different Voice of Jewish Women Rabbi Amy Eilberg . Acknowledgments . Introduction ......................................... What You Need to Know to Use This Book . Rabbinic Commentators and Midrashic Collections Noted in This Book . Bereshit/Genesis Bereshit ₍:‒:₎: The Untold Story of Eve Rabbi Lori Forman . Noach ₍:‒:₎: Mrs. Noah Rabbi Julie RingoldSpitzer . Lech Lecha ₍:‒:₎: What’s in a Name? Rabbi Michal Shekel. Va ye r a ₍:‒:₎: Positive Pillars Rabbi Cynthia A. Culpeper . Chaye Sarah ₍:‒:₎: Woman’s Life, Woman’s Truth Rabbi Rona Shapiro . Toldot ₍:‒:₎: Rebecca’s Birth Stories Rabbi Beth J. Singer. Vayetze ₍:‒:₎: Wrestling on the Other Side of the River Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso . Contents Vayishlach ₍:‒:₎: No Means No Rabbi Lia Bass. Vayeshev ₍:‒:₎: Power, Sex, and Deception Rabbi Geela-Rayzel Raphael . Miketz ₍:‒:₎: In Search of Dreamers Rabbi Debra Judith Robbins . Vayigash ₍:‒:₎: Daddy’s Girl Rabbi Shira Stern . Va ye c h i ₍:‒:₎: Serach Bat Asher—the Woman Who Enabled the Exodus Rabbi Barbara Rosman Penzner. Shmot/Exodus Shmot ₍:‒:₎: Rediscovering Tziporah Rabbi Rebecca T. Alpert . Va-era ₍:‒:₎: The Many Names of God Rabbi Karyn D. Kedar . Bo ₍:‒:₎: Power and Liberation Rabbi Lucy H.F. Dinner. Beshalach ₍:‒:₎: Miriam’s Song, Miriam’s Silence Rabbi Sue Levi Elwell . Yitro ₍:‒:₎: We All Stood at Sinai Rabbi Julie K.Gordon . Mishpatim ₍:‒:₎: What Must We Do? Rabbi Nancy Fuchs-Kreimer . Terumah ₍:‒:₎: Community as Sacred Space Rabbi Sharon L. Sobel . Tetzaveh ₍:‒:₎: Finding Our Home in the Temple and the Temple in Our Homes Rabbi Sara Paasche-Orlow . Contents Ki Tissa ₍:‒:₎: The Women Didn’t Build the Golden Calf—or Did They? Rabbi Ellen Lippmann . Vayakhel ₍:‒:₎: Of Women and Mirrors Rabbi Nancy H.