Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rncm Chamber Music Festival Songs Without Words Rncm Chamber Music Festival Songs Without Words

Friday 04 – Sunday 06 March 2016 RNCM CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL SONGS WITHOUT WORDS RNCM CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL SONGS WITHOUT WORDS WELCOME The RNCM Chamber Music Festival plays an enormous role in the story of the College and is a major event in our calendar. Chamber music is at the core at what we do - the RNCM has a proud tradition of chamber ensemble training and our alumni appear with high profile ensembles such as the Elias, Heath and Navarra String Quartets plus the Gould Piano Trio to name but a few. Every year, the Chamber Music Festival goes from strength to strength, presenting the opportunity to see our wonderful students, internationally renowned staff and special guests perform beautiful music across a jam-packed weekend. This year is no exception, as we explore German Romanticism in Songs Without Words. We focus particularly on the music of Mendelssohn and Schumann and our students will be involved in a major composition project, as they are asked to create responses to Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. So the Festival will include works from across the 19th century but will also dip into the 20th century with composers such as Richard Strauss. This year’s line-up features some of the finest musicians performing today including the Talich Quartet, Elias Quartet, Michelangelo Quartet, plus RNCM Junior Fellows the Solem Quartet and our International Artist chamber ensemble the Diverso String Quartet. We also welcome chamber groups from Chetham’s, St Mary’s, Junior RNCM, the Royal Irish Academy of Music and Sheffield Music Academy. So please join us and immerse yourself in this weekend of lush musical landscapes. -

Die Orchestersinfonien Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdys Studien Zum Gegenwärtigen Fachdiskurs

Die Orchestersinfonien Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdys Studien zum gegenwärtigen Fachdiskurs Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Silke Gömann aus Holzminden Bonn 1999 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 0. VORWORT............................................................................................................................ V 1. EINLEITUNG .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Methodische Vorbemerkung ................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Einführung in die Untersuchungsperspektive ........................................................................ 8 2. ‘IDEALE KÜNSTLERBIOGRAPHIE’ .................................................................................... 13 2.1 Narrationsmodelle und der Rückgriff auf die Einteilung in Phasen ..................................... 22 2.2 Interdependenzen: Der Diskurs über die Orchestersinfonien im Kontext der Diskussion einer künstlerischen Entwicklung des Komponisten........................................................... 55 2.2.1 Der Diskurs über Mendelssohns c-moll Sinfonie als „symphonischer Anfang“.................. 62 2.2.2 Der mühsame Weg zur ‘Schottischen Sinfonie’ – Der Diskurs über die a-moll Sinfonie als sinfonisches Hauptwerk des Komponisten ................................................................... 91 2.2.3 -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

The "Lobgesang." a Comparison of the Original and Revised Scores Author(S): Joseph Bennett Source: the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol

The "Lobgesang." A Comparison of the Original and Revised Scores Author(s): Joseph Bennett Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 29, No. 545 (Jul. 1, 1888), pp. 393-396 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3360757 Accessed: 06-02-2016 19:10 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 202.28.191.34 on Sat, 06 Feb 2016 19:10:08 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1888. THE MUSICAL TIMES.-JuLY I, 393 (November 18, 1840) to Carl Klingemann in terms as THE MUSICAL TIMES thus:-- AND SINGING-CLASS CIRCULAR, " My ' Hymn of Praise' is to be performedat the end of this month for the benefit of old invalided 1888. JULY I, musicians. I am determined,however, that it shall not be produced in the imperfect form in which, THE " LOBGESANG." owing to my illness, it was given in Birmingham, so A COMPARISON OF THE ORIGINAL AND REVISED that makes me work hard. -

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring English Translation

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) English Translation: William Bartholomew PART ONE The Biblical tale of Elijah dates from c. 800 BCE. "In fact I imagined Elijah as a real prophet The core narrative is found in the Book of Kings through and through, of the kind we could (I and II), with minor references elsewhere in really do with today: Strong, zealous and, yes, the Hebrew Bible. The Haggadah supplements even bad-tempered, angry and brooding — in the scriptural account with a number of colorful contrast to the riff-raff, whether of the court or legends about the prophet’s life and works. the people, and indeed in contrast to almost the After Moses, Abraham and David, Elijah is the whole world — and yet borne aloft as if on Old Testament character mentioned most in the angels' wings." – Felix Mendelssohn, 1838 (letter New Testament. The Qu’uran also numbers to Julius Schubring, Elijah’s librettist) Elijah (Ilyas) among the major prophets of Islam. Elijah’s name is commonly translated to mean “Yahweh is my God.” PROLOGUE: Elijah’s Curse Introduction: Recitative — Elijah Elijah materializes before Ahab, king of the Four dark-hued chords spring out of nowhere, As God the Lord of Israel liveth, before Israelites, to deliver a bitter curse: Three years of grippingly setting the stage for confrontation.1 whom I stand: There shall not be dew drought as punishment for the apostasy of Ahab With the opening sentence, Mendelssohn nor rain these years, but according to and his court. The prophet’s appearance is a introduces two major musical motives that will my word. -

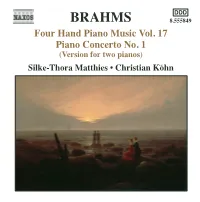

Brahms 17 US 9/10/06 5:15 Pm Page 4

555849bk Brahms 17 US 9/10/06 5:15 pm Page 4 held until 1868, when he moved to Berlin. His protagonist, better known perhaps as the False Dmitry, DDD employment in Hanover allowed him time for is more familiar from Russian operatic treatments of this composition, and among fifty works from this period of episode in their history. Brahms, who had already BRAHMS 8.555849 his life were two violin concertos and four concert transcribed Joachim’s Shakespearian Hamlet Overture overtures. The second of these last was his Demetrius for piano duet and his Henry IV for two pianos, arranged Overture, Op. 6, based on the 1854 tragedy by Hermann the Demetrius Overture, which Joachim had dedicated Grimm, son of Wilhelm Grimm, responsible, with his to Franz Liszt, with whom he was to break definitively Four Hand Piano Music Vol. 17 brother Jakob, for the famous Kinder- und Hausmärchen in 1857, for two pianos, completing it during the first (Grimms’ Fairy Tales). The play itself, not a great years of his friendship with the composer. Piano Concerto No. 1 success at its first staging, treats the same subject as Schiller’s unfinished drama of the same name. The Keith Anderson (Version for two pianos) The Demetrius Overture was recorded using the manuscript with the signature “Nachlass Joseph Joachim, Musikalien, Nr. 22”, kept by the Staats and Hamburg University Library “Carl von Ossietzky”. Silke-Thora Matthies • Christian Köhn Silke-Thora Matthies and Christian Köhn The pianists Silke-Thora Matthies and Christian Köhn, with individual solo careers, came together in 1986 to form a piano duo and played their first concert in public the last day of October 1988. -

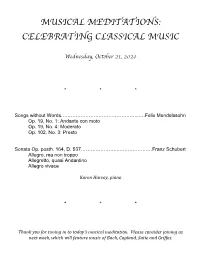

Musmeds&Notes-October 21, 2020

MUSICAL MEDITATIONS: CELEBRATING CLASSICAL MUSIC Wednesday, October 21, 2020 * * * Songs without Words………………………………………...….Felix Mendelssohn Op. 19, No. 1: Andante con moto Op. 19, No. 4: Moderato Op. 102, No. 3: Presto Sonata Op. posth. 164, D. 537…………………..…………………Franz Schubert Allegro, ma non troppo Allegretto, quasi Andantino Allegro vivace Karen Harvey, piano * * * Thank you for tuning in to today’s musical meditation. Please consider joining us next week, which will feature music of Bach, Copland, Satie and Griffes. Notes on today’s music Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (February 3, 1809 – November 4, 1847), a.k.a. Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions incluDe symphonies, concertos, piano music, organ music and chamber music. His best-known works incluDe the overture and incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream (containing the famous Wedding March), the Italian Symphony, the Scottish Symphony, the oratorio St. Paul, the oratorio Elijah, the overture The Hebrides, the mature Violin Concerto and the String Octet. The meloDy for the Christmas carol "Hark! The HeralD Angels Sing" is also his. Songs Without Words are his most famous solo piano compositions. A grandson of the philosopher Moses MenDelssohn, Felix MenDelssohn was born into a prominent Jewish family, anD though he was recogniseD early as a musical proDigy, his parents were cautious and did not seek to capitalise on his talent. MenDelssohn enjoyeD early success in Germany, anD singlehandedly reviveD interest in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach with his performance of the St. Matthew Passion in 1829. -

Words Without Music Free

FREE WORDS WITHOUT MUSIC PDF Philip Glass | 432 pages | 02 Apr 2015 | FABER & FABER | 9780571323722 | English | London, United Kingdom WORDS WITHOUT MUSIC | Kirkus Reviews An award-winning team of journalists, designers, and videographers who tell brand stories through Fast Company's distinctive lens. Leaders who are shaping the future of business in creative ways. New workplaces, new food sources, new medicine--even an entirely new economic system. Want to stream Heroes, read the interactive novel, then bid online for artwork from the show? Thank Comstock for all that, too. The economics of television used to be simple. Do you understand how to make money today, when I can watch 30 Rock pretty much Words Without Music We understand it a lot better than we used to. Digital media allow us to open up new windows without the cannibalization you might expect. So yes, we can offer 30 Rock in preview, then on-air, then streaming, then iTunesthen mobile, and then syndication. Some know what they want, some less so. They expect us to Words Without Music in on targeted consumers: What do we know about them, and how do we reach them? A lot of those are repeat viewers. Others are time-shifting. It has to. We have to find the right solution. Words Without Music personal expression [by viewers], the desire to be involved in the storytelling. With success, you get a bit more confident. But we still have to be more focused and more Words Without Music. This business is hypersensitive like that. You have to pick a path, keep to it, and feel good about it. -

Purcell, Handel, Haydn, and Mendelssohn Anniversary Reflections

Purcell, Handel, Haydn, and Mendelssohn Anniversary Reflections March 2009 Martin Adams Trinity College, Dublin "That what took least, was really best": tensions between the private and public aspects of Purcell's compositional thought. Roger North remembered that Purcell "used to mark what did not take for the best musick, it being his constant observation that what took least, was really best." Purcell's penchant for complexity has been discussed widely; and Alan Howard has recently said that aspects of the composer's practice set him "somewhat apart from contemporary composers and, even more importantly, from the expectations of his audiences." They also set him somewhat apart from the other composers in this conference. My paper will argue that this apartness is rooted in a tension between expectations - those towards himself and towards his paying audience. It is a tension between the private and the public, the private epitomised in music of a "highbrow" kind (whatever its intended audience), and the public epitomised in his theatre music. Via a comparison of works private (especially songs from Harmonia Sacra) and public (mainly theatre songs), the paper will define the thinking and practice that differentiates the two spheres. It will also suggest that the private sphere was so deeply embedded that Purcell's reputation inevitably rests on a small number of works. In that respect too, he makes a revealing comparison with the other composers in this conference. Maria Teresa Arfini Milan and Aosta University Music as Autobiography: Mendelssohn between Beethoven and Schumann There are some compositions where Mendelssohn shows actually autobiographical traits. -

Zum Gedenken an Renate Groth (1940–2014) 7

Arbeitsgemeinschaft für rheinische Musikgeschichte Mitteilungen 96 Juli 2016 Herausgeber: Arbeitsgemeinschaft für rheinische Musikgeschichte e.V. Institut für Historische Musikwissenschaft der Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln Unter Krahnenbäumen 87, 50668 Köln Redaktion: Fabian Kolb Druck: Jürgen Brandau Druckservice, Köln © 2016 ISSN 0948-1222 MITTEILUNGEN der Arbeitsgemeinschaft für rheinische Musikgeschichte e.V. Nr. 96 Juli 2016 Inhalt Inga Mai Groote Zum Gedenken an Renate Groth (1940–2014) 7 Hans Joachim Marx Zum Gedenken an Günther Massenkeil (1926–2014) 8 Klaus Wolfgang Niemöller Zum Gedenken an Detlef Altenburg (1947–2016) 9 Joachim Dorfmüller Ein reiches Wissenschaftlerleben – Gedenkblatt für Prof. Dr. Heinrich Hüschen anlässlich seines 100. Geburtstags am 2. März 2015 10 Norbert Jers Dietrich Kämper 80 Jahre 13 Klaus Wolfgang Niemöller Das Sängerfest des Deutsch-flämischen Sängerbundes 1846 in Köln unter Leitung von Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy und Franz Weber. Die Chorpartitur der Gesänge und das Festprogrammbuch im Kontext der Mitwirkenden 15 Franz-Josef Vogt Die Orgel der kath. Pfarrkirche St. Bartholomäus in Köln-Porz-Urbach 37 Arnold Jacobshagen 1863 – Der Kölner Dom und die Musik 44 Fabian Kolb Max Bruch – Neue Perspektiven auf Leben und Werk 46 6 Robert von Zahn Wie preußisch klang das Rheinland? Eine Tagung bilanzierte 48 Robert von Zahn Das Beethoven-Haus während des Nationalsozialismus 50 Leitungswechsel im Deutschen Musikinformationszentrum 53 Protokoll der Mitgliederversammlung 2015 54 7 Inga Mai Groote Zum Gedenken an Renate Groth (1940–2014)* Am 11. September 2014 verstarb mit Renate Groth eine engagierte Vermittlerin zwischen Musikwissenschaft und Musiktheorie. Nach dem Studium der Schulmusik mit dem instru- mentalen Hauptfach Viola da gamba und den Nebenfächern Anglistik und Philosophie und Tätigkeit im Schuldienst unterrichtete sie an der Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hanno- ver, wo sie ab 1982 eine Professur für Musiktheorie innehatte. -

Program Notes

March 16-17, 2019, page 1 programBY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA notes , Fantasy- theme suggests the fury and confusion Romeo and Juliet of a fight. The love theme (used here Overture (1869) as a contrasting second theme) repre- ■ PETER ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY 1840- sents Romeo’s passion; a tender, sighing 1893 phrase for muted violins suggests Juliet’s Romeo and Juliet was written when response. A stormy development section Tchaikovsky was 29. It was his first denotes the continuing feud and Friar masterpiece. For a decade, he had been Lawrence’s pleas for peace. The crest of involved with the intense financial, per- the fight ushers in the recapitulation, in sonal and artistic struggles that mark the which the thematic material from the ex- maturing years of most creative figures. position is considerably compressed. The Advice and guidance often flowed his tempo slows, the mood darkens, and the way during that time, and one who dis- coda emerges with a sense of impend- pensed it freely to anyone who would lis- ing doom. A funereal drum beats out ten was Mili Balakirev, one of the group the cadence of the lovers’ fatal pact. The of amateur composers known in English closing woodwind chords evoke visions as “The Five” (and in Russian as “The of the flight to celestial regions. Mighty Handful”) who sought to create a nationalistic music specifically Russian Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, in style. In May 1869, Balakirev sug- Op. 26 (1865-1866) gested to Tchaikovsky that Shakespeare’s MAX BRUCH ■ 1838-1920 Romeo and Juliet would be an appropri- ate subject for a musical composition, German composer, conductor and and he even offered the young composer teacher Max Bruch, widely known and a detailed program and an outline for the respected in his day, received his earli- form of the piece. -

Van Cott Information Services (Incorporated 1990) Offers Books

Clarinet Catalog 9a Van Cott Information Services, Inc. 02/08/08 presents Member: Clarinet Books, Music, CDs and More! International Clarinet Association This catalog includes clarinet books, CDs, videos, Music Minus One and other play-along CDs, woodwind books, and general music books. We are happy to accept Purchase Orders from University Music Departments, Libraries and Bookstores (see Ordering Informa- tion). We also have a full line of flute, saxophone, oboe, and bassoon books, videos and CDs. You may order online, by fax, or phone. To order or for the latest information visit our web site at http://www.vcisinc.com. Bindings: HB: Hard Bound, PB: Perfect Bound (paperback with square spine), SS: Saddle Stitch (paper, folded and stapled), SB: Spiral Bound (plastic or metal). Shipping: Heavy item, US Media Mail shipping charges based on weight. Free US Media Mail shipping if ordered with another item. Price and availability subject to change. C001. Altissimo Register: A Partial Approach by Paul Drushler. SHALL-u-mo Publications, SB, 30 pages. The au- Table of Contents thor's premise is that the best choices for specific fingerings Clarinet Books ....................................................................... 1 for certain passages can usually be determined with know- Single Reed Books and Videos................................................ 6 ledge of partials. Diagrams and comments on altissimo finger- ings using the fifth partial and above. Clarinet Music ....................................................................... 6 Excerpts and Parts ........................................................ 6 14.95 Master Classes .............................................................. 8 C058. The Art of Clarinet Playing by Keith Stein. Summy- Birchard, PB, 80 pages. A highly regarded introduction to the Methods ........................................................................ 8 technical aspects of clarinet playing. Subjects covered include Music .........................................................................