Running Radio Selam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelical Friend, February 1973 (Vol. 6, No. 6)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Evangelical Friend (Quakers) 2-1973 Evangelical Friend, February 1973 (Vol. 6, No. 6) Evangelical Friends Alliance Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_evangelical_friend Recommended Citation Evangelical Friends Alliance, "Evangelical Friend, February 1973 (Vol. 6, No. 6)" (1973). Evangelical Friend. 92. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_evangelical_friend/92 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Evangelical Friend by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. February 1973 Vol. VI, No. 6 l!fuvEJT IN THE BEAUTIFUL NORTHWEST LIFE is what George Fox College is all about. Academic LIFE of the highest quality. Spiritual LIFE of vigorous vitality. Social LIFE with meaningful relationships. A total campus LIFE that is Christocentric. If you desire to live a life of meaningful relationships now while preparing for a greater service to God and mankind . .. then George Fox College, a private Christian College in Newberg, Oregon, is the place. Clip this coupon for more information Send to: NAME __________________________________________ ADDRESS _____________________________________ Admissions Office ----------------------------------- ZIP _________ GEORGE FOX COLLEGE YEAR IN SCHOOL _____ Newberg, Oregon 97132 PHONE ________________ 2 Evangelical Friend Evangelical Friend Contents Editor-in-Chief: Jack L. Willcuts Managing Editor: Harlow Ankeny Editorial Assistants: Earl P. Barker, Kelsey E and Rachel Hinshaw Art Director: Stan Putman. Department Editors: Esther Hess, Mission ary Voice; Betty Hockett, Children's Page; Walter P. -

PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016

/robertmillergallery For immediate release: [email protected] @RMillerGallery 212.366.4774 /robertmillergallery PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016 New York, NY – February 17, 2016. Robert Miller Gallery is pleased to announce Eighteen Stations, a special project by Patti Smith. Eighteen Stations revolves around the world of M Train, Smith’s bestselling book released in 2015. M Train chronicles, as Smith describes, “a roadmap to my life,” as told from the seats of the cafés and dwellings she has worked from globally. Reflecting the themes and sensibility of the book, Eighteen Stations is a meditation on the act of artistic creation. It features the artist’s illustrative photographs that accompany the book’s pages, along with works by Smith that speak to art and literature’s potential to offer hope and consolation. The artist will be reading from M Train at the Gallery throughout the run of the exhibition. Patti Smith (b. 1946) has been represented by Robert Miller Gallery since her joint debut with Robert Mapplethorpe, Film and Stills, opened at its 724 Fifth Avenue location in 1978. Recent solo exhibitions at the Gallery include Veil (2009) and A Pythagorean Traveler (2006). In 2014 Rockaway Artist Alliance and MoMA PS1 mounted Patti Smith: Resilience of the Dreamer at Fort Tilden, as part of a special project recognizing the ongoing recovery of the Rockaway Peninsula, where the artist has a home. Smith's work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions worldwide including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2013); Detroit Institute of Arts (2012); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford (2011); Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporaine, Paris (2008); Haus der Kunst, Munich (2003); and The Andy Warhol Museum (2002). -

FWN 172.Qxd 24/04/2013 10:53 Page 1

FWN 172.qxd 24/04/2013 10:53 Page 1 Number 172 2010/1 Friends World News The Bulletin of the Friends World Committee for Consultation Friends World Committee for Consultation Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) FWN 172.qxd 24/04/2013 10:53 Page 2 Page 2 Friends World News 2010/1 From the World Office Threads It takes a variety of threads to make fabric and FWCC Friends have to say on the spiritual dimensions of is fabric in the making. Right now the major threads this global issue? Regional coordinators are being iden- are planning for the World Conference in 2012 and tified, and in the meantime, clusters may take place at activating the cluster process of our consultation on any time. Funding permitting, more yearly meetings Friends' responses to global change. Both are getting can receive staff support locally. Responses are stronger, more colourful, more textured – and more being gathered on the website: www.fwccglob- entwined. It is exciting to watch this fabric take alchange.org. shape. FWCC has numerous other threads, some more vis- Yearly meetings have been asked to designate their ible than others. These are called Quaker UN work in allotted delegates to the world conference by the end New York, Geneva and Vienna, international mem- of this year. The International Planning Committee, bership for isolated individuals and growing groups, co-clerked by Elizabeth Gates of Philadelphia YM and continuing networking among Friends organisa- and Pradip Lamachhane of Nepal YM, has met at the tions and yearly meetings. site Kabarak University near Nakuru, Kenya and developed a structure for the programme centred With this fabric coming into being, FWCC is becoming around worship and our experiences of the theme: more visible to new faces in the Quaker world. -

Triptych Eyes of One on Another

Saturday, September 28, 2019, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Triptych Eyes of One on Another A Cal Performances Co-commission Produced by ArKtype/omas O. Kriegsmann in cooperation with e Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by korde arrington tuttle Featuring words by Essex Hemphill and Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran and Isaiah Robinson Jennifer H. Newman, associate director/touring Lilleth Glimcher, associate director/development Brad Wells, music director and conductor Martell Ruffin, contributing choreographer and performer Carlos Soto, set and costume design Yuki Nakase, lighting design Simon Harding, video Dylan Goodhue/nomadsound.net, sound design William Knapp, production management Talvin Wilks and Christopher Myers, dramaturgy ArKtype/J.J. El-Far, managing producer William Brittelle, associate music director Kathrine R. Mitchell, lighting supervisor Moe Shahrooz, associate video designer Megan Schwarz Dickert, production stage manager Aren Carpenter, technical director Iyvon Edebiri, company manager Dominic Mekky, session copyist and score manager Gill Graham, consulting producer Carla Parisi/Kid Logic Media, public relations Cal Performances’ 2019 –20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ROOMFUL OF TEETH Estelí Gomez, Martha Cluver, Augusta Caso, Virginia Kelsey, omas McCargar, ann Scoggin, Cameron Beauchamp, Eric Dudley SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS Lisa Oman, executive director ; Eric Dudley, artistic director Susan Freier, violin ; Christina Simpson, viola ; Stephen Harrison, cello ; Alicia Telford, French horn ; Jeff Anderle, clarinet/bass clarinet ; Kate Campbell, piano/harmonium ; Michael Downing and Divesh Karamchandani, percussion ; David Tanenbaum, guitar Music by Bryce Dessner is used with permission of Chester Music Ltd. “e Perfect Moment, For Robert Mapplethorpe” by Essex Hemphill, 1988. -

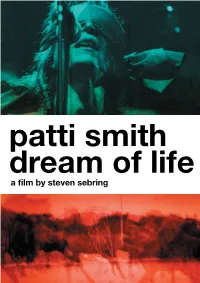

Patti DP.Indd

patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring THIRTEEN/WNET NEW YORK AND CLEAN SOCKS PRESENT PATTI SMITH AND THE BAND: LENNY KAYE OLIVER RAY TONY SHANAHAN JAY DEE DAUGHERTY AND JACKSON SMITH JESSE SMITH DIRECTORS OF TOM VERLAINE SAM SHEPARD PHILIP GLASS BENJAMIN SMOKE FLEA DIRECTOR STEVEN SEBRING PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW SCOTT VOGEL PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP HUNT EXECUTIVE CREATIVE STEVEN SEBRING EDITORS ANGELO CORRAO, A.C.E, LIN POLITO PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW CONSULTANT SHOSHANA SEBRING LINE PRODUCER SONOKO AOYAGI LEOPOLD SUPERVISING INTERNATIONAL PRODUCERS JUNKO TSUNASHIMA KRISTIN LOVEJOY DISTRIBUTION BY CELLULOID DREAMS Thirteen / WNET New York and Clean Socks present Independent Film Competition: Documentary patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring USA - 2008 - Color/B&W - 109 min - 1:66 - Dolby SRD - English www.dreamoflifethemovie.com WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY 2 rue Turgot Sundance office located at the Festival Headquarters 75009 Paris, France Marriott Sidewinder Dr. T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 Jeff Hill – cell: 917-575-8808 [email protected] E: [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com Michelle Moretta – cell: 917-749-5578 E: [email protected] synopsis Dream of Life is a plunge into the philosophy and artistry of cult rocker Patti Smith. This portrait of the legendary singer, artist and poet explores themes of spirituality, history and self expression. Known as the godmother of punk, she emerged in the 1970’s, galvanizing the music scene with her unique style of poetic rage, music and trademark swagger. -

The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism Edited by Stephen W

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13660-1 — The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism Edited by Stephen W. Angell , Pink Dandelion Frontmatter More Information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO QUAKERISM The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism offers a fresh, up-to-date, and acces- sible introduction to Quakerism. Quakerism is founded on radical ideas and its history of constancy and change offers fascinating insights into the nature of nonconformity. In a series of eighteen essays written by an international team of scholars, and commissioned especially for this volume, the Companion covers the history of Quakerism from its origins to the present day. Employing a range of methodologies, it features sections on the History of Quaker Faith and Practice, Expressions of Quaker Faith, Regional Studies, and Emerging Spiritualities. It also examines all branches of Quakerism, including evangelical, liberal, and conservative, as well as non-theist Quakerism and convergent Quaker thought. This Companion will serve as an essential resource for all interested in Quaker thought and practice. Stephen W. Angell is Leatherock Professor of Quaker Studies at the Earlham School of Religion. He has published extensively in the areas of Quaker Studies and African-American Religious Studies. Pink Dandelion directs the work of the Centre for Research in Quaker Studies, Woodbrooke, and is Professor of Quaker Studies at the University of Birmingham and a Research Fellow at Lancaster University. He is the author and editor of a number of books, most recently (with Stephen Angell) Early Quakers and Their Theological Thought. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13660-1 — The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism Edited by Stephen W. -

Addis Ababa University History of Radio Ethiopia from 1974 to 2000 A

Addis Ababa University History of Radio Ethiopia from 1974 to 2000 A Thesis Submitted To College Of Social Sciences Addis Ababa University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History By Tsigereda Siyoum Addis Ababa 2019 Addis Ababa University College Of Social Sciences By Tsigereda Siyoum Approved by Board of Examiners ___________________ ______________________ Advisor __________________ ______________________ Advisor __________________ ______________________ Examiner __________________ ______________________ Examiner Table of Content Content Page Acknowledgement I Preface II Abstract III List of Abbreviations V CHAPTER ONE Background 1 1.1. History of Radio Broadcasting: In Global Context ……………………………………… 1 1.2. Historical Development of Radio Broadcasting in Ethiopia (1933-1974) ……………….. 5 1.3.Role of Radio Ethiopia During the Imperial Period 21 CHAPTER TWO Radio Ethiopia during the Derg Period From 1974 to1991 27 2.1. Institutional Transformation …………………………………………………………….. 27 2.2. The Nationalization of Private Radio Station ……………………………………………. 29 2.3. National Service and International Service 32 2.4. Regional Service 33 2.5. Medium of Transmission 34 2.6. Programs 38 2.7. Role of Voice of Revolutionary Ethiopia 45 2.7.1. Keeping the National Unity 45 2.7.2. The Propagation of Anti- White Minority Rule 60 2.7.3. Encouragement of Education 62 2.7.4. Promotion of Socio- Economic Development 66 CHAPTER THREE Radio Ethiopia from 1991-2000 71 3.1. Language Service 77 3.2. News Agencies 78 3.3. Research Based Programs 80 3.4. Ethiopia Radio Air Time Coverage 82 3.5. Ethiopian Mass Media Training Institute (EMMTI) 86 3.6 FM Service 87 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 92 Acknowledgement First of all, I would like to thank God, the beginning and the end of my life, for his countless providence throughout the course of my study. -

TURNING HEARTS to BREAK OFF the YOKE of OPPRESSION': the TRAVELS and SUFFERINGS of CHRISTOPHER MEIDEL C

Quaker Studies Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 5 2008 'Turning Hearts to Break Off the okY e of Oppression': The rT avels and Sufferings of Christopher Meidel, c. 1659-c. 1715 Richard Allen University of Wales Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Allen, Richard (2008) "'Turning Hearts to Break Off the oY ke of Oppression': The rT avels and Sufferings of Christopher Meidel, c. 1659-c. 1715," Quaker Studies: Vol. 12: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol12/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUAKER STUDIES 1211 (2007) (54-72] ISSN 1363-013X 'TURNING HEARTS TO BREAK OFF THE YOKE OF OPPRESSION': THE TRAVELS AND SUFFERINGS OF CHRISTOPHER MEIDEL c. 1659-c. 1715* Richard Allen University of Wales ABSTRACT This study of Christopher Meidel, a Norwegian Quaker writer imprisoned both in England and on the Continent for his beliefs and actions, explores the life of a convert to Quakerism and his missionary zeal in the early eighteenth century. From Meidel's quite tempestuous career we receive insights into the issues Friends faced in Augustan England in adapting to life in a country whose inter-church relations were largely governed by the 1689 Toleration Act, and its insistence that recipients of toleration were to respect the rights of other religionists. -

Switzerland Yearly Meeting History and Biography Project a Resource

Summer 2005 Switzerland Yearly Meeting History and Biography Project “Let Their Lives Speak” A Resource Book. prepared by Michael and Erica Royston SYM History and Biography Project Summer 2005 Page 1 SYM History and Biography Project Summer 2005 Page 2 Table of contents Abbreviations 8 Introduction 9 Why the Project? ________________________________________________________ 9 What does it mean “Letting Their Lives Speak”? _____________________________ 9 Who is in the list?________________________________________________________ 9 This is a resource book. __________________________________________________ 10 Thanks. ______________________________________________________________ 10 Section 1. Concerning People. 11 Allen, William__________________________________________________________ 11 Ansermoz, Félix and Violette._____________________________________________ 11 Ashford, Oliver and Lilias________________________________________________ 11 Ayusawa, Iwao and Tomiko.______________________________________________ 12 Balch, Emily Greene.____________________________________________________ 12 Béguin, Max-Henri. _____________________________________________________ 12 Bell, Colin and Elaine. ___________________________________________________ 12 Berg, Lisa and Wolf. ____________________________________________________ 12 Bieri, Sigrid____________________________________________________________ 13 Bietenholz, Alfred. ______________________________________________________ 13 Bohny, August and Friedel . ______________________________________________ -

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) The New Wave (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") New York's new Boheme TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. 1976 was a watershed year: the music industry was revitalized by the emergence of "independent" labels and the music scene was revitalized by the emergence of new genres. The two phenomena fed into each other and spiraled out of control. In a matter of months, a veritable revolution changed the way music was produced, played and heard. The old rock stars were forgotten and new rock stars began setting new trends. As far as white popular music goes, it was a sort of Renaissance after a few years of burgeoisie icons (think: Bowie), conservative sounds (country-rock, southern boogie) and exploitation of minorities (funk, reggae). During the 1970s alternative rock had survived in niches that were highly intellectual, namely German rock and progressive-rock (particularly the Canterbury school). They were all but invisible to the masses. 1976 was the year when most of those barriers (between "low" and "high" rock, between "intellectual" and "populist", between "conservative" and "progressive", between "star" and "anti-star") became not only obsolete but meaningless. -

(Quakers) in Britain Epistles & Testimonies

Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Epistles & testimonies Compiled for Yearly Meeting, Friends House, London, 27–30 May 2016 Epistles & testimonies Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) In Britain Documentation in advance of Yearly Meeting to be held at Friends House, London, 27–30 May 2016 Epistles & testimonies is part of a set of publications entitled The Proceedings of the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain 2016, published by Britain Yearly Meeting. The full set comprises the following documents: 1. Documents in advance, including agenda and introductory material for Yearly Meeting 2016 and the annual reports of Meeting for Sufferings and Quaker Stewardship Committee 2. Epistles & testimonies 3. Minutes, to be distributed after the conclusion of Yearly Meeting 4. The formal Trustees’ annual report and Financial statements for the year ended December 2015 5. Tabular statement. Please address enquiries to: Yearly Meeting Office Britain Yearly Meeting Friends House 173 Euston Road London NW1 2BJ Telephone: 020 7663 1000 Email: [email protected] All documents issued are also available as PDFs and for e-readers at www.quaker.org.uk/ym. Britain Yearly Meeting is a registered charity, number 1127633. Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain Epistles & testimonies Epistles Introduction to epistles from Quaker World Relations Committee 7 From Europe and Middle East 9 Belgium and Luxembourg Yearly Meeting 9 Europe & -

Among Friends Issue

Among FriendsNo 107: Summer 2007 Published by the Europe and Middle East Section of Friends World Committee for Consultation Executive Secretary: Bronwyn Harwood, 1 Cluny Terrace, Edinburgh EH10 4SW, UK. Tel: +44 (0)131 466 1263; [email protected] Finding the Prophetic Voice for our Time Follow the way of love and eagerly desire spiritual gifts, especially the gift of prophecy. 1 Corinthians 14:1, NRSV It is love, then, that you should strive for. Set your hearts on spiritual gifts, especially the gift of proclaiming God’s message. 1 Corinthians 14:1 TEV-Good News for Modern Man Welcome and greetings from Europe and Middle East Section to Friends from around the world meetings gather for nine days not only to conduct travelling to Dublin, Ireland, for the 22nd Triennial business but also to grow in the life of Christ and the of Friends World Committee for Consultation Holy Spirit by discovering together their common which will take place 11 – 19 August. And thank spiritual ground. you to the Irish Friends and the World Office team The work of the gathering is not only the who have been working so hard for many months administrative business of FWCC, but also the now to prepare for our arrival. exchanges and communication among Friends The Triennial is the business meeting for the Friends worldwide about the work of Friends in the world World Committee for Consultation. Every three and our joy in living our faith. It is a time to learn years, the representatives named by their yearly about each other and the challenges and successes of other yearly meetings.