Hezekiah and the Dialogue of Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15. Bible Marking

LESSON FIFTEEN Hezekiah: The Challenge from Assyria Quote: “He trusted in the LORD God of Israel; so that after him was none like him among all the kings of Judah, nor any that were before him. For he clave to the LORD, and departed not from following him, but kept his commandments, which the LORD commanded Moses.” 2 Kings 18:5, 6 Bible Marking Hezekiah - 2 Kings 18 2 Kings 18:1 - “Hezekiah” - Means “strengthened of Yahweh”. It was only through Yahweh’s strength that the reformation was accomplished, that Hezekiah was healed, and that Assyria was defeated. So great was Hezekiah, that we are given 3 records of his life (Kings, Chronicles and Isaiah). A Reformation on Divine Principles Mark above & “Ahaz” - Means “possessor”, ie. a selfish man, below 2 Kg 18 who was Judah’s worst king Ahaz had given himself over to idolatry, following the examples of those who had left the truth (2 Chron 28:1-2), and 2 Kings 18:2 - “Abi” - The margin has - ‘Abijah, of the world in general (2 Kg 16:3, 10-11). He therefore made 2 Chron 29:1’. “Abijah” means “Yah is Father”. Judah “naked” in the sight of Yahweh, and “transgressed sore She appears to be the inspiration for Hezekiah to against Yahweh” (2 Chron 28:19). Now Hezekiah brought devote his life to the service of Yahweh. See about a reformation upon Divine principles. He turned the Prov 22:6. people back to Yahweh and His Word and to the Pioneers of “Zachariah” - Means “Yahweh hath remembered” the truth (David, Asaph and Gad and Nathan etc). -

1-And-2 Kings

FROM DAVID TO EXILE 1 & 2 Kings by Daniel J. Lewis © copyright 2009 by Diakonos, Inc. Troy, Michigan United States of America 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Composition and Authorship ...................................................................................................................... 5 Structure ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Theological Motifs ..................................................................................................................................... 7 The Kingship of Solomon (1 Kings 1-11) .....................................................................................................13 Solomon Succeeds David as King (1:1—2:12) .........................................................................................13 The Purge (2:13-46) ..................................................................................................................................16 Solomon‟s Wisdom (3-4) ..........................................................................................................................17 Building the Temple and the Palace (5-7) .................................................................................................20 The Dedication of the Temple (8) .............................................................................................................26 -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Hezekiah's Prayer 2 Kings 18-19 Characters: Narrator, Sennacherib

1 Hezekiah’s Prayer 2 Kings 18-19 Characters: Narrator, Sennacherib, Isaiah, Hezekiah, Messenger Narrator: God’s land had been split into two kingdoms—Israel and Judah. Israel had been ruled by very unfaithful kings, and none of the Israelites had believed in God anymore. Judah had once been ruled by Ahaz, who was a very sinful king, and had built false altars around the kingdom. When his son Hezekiah became king, Hezekiah ruled that all the false idols be burned. Hezekiah: I decree that all the false idols be burned! Also, I order that the bronze serpent Moses built be destroyed, as the people have started worshipping it as a god. The people will only worship the one true God, the Lord! Narrator: God found favor with Hezekiah for destroying all of the idols in the land. Sometime during Hezekiah’s reign, the Assyrians came and conquered the land of Israel. God allowed Israel to be conquered because they had stopped worshipping Him. Soon, the Assyrians began to attack cities in Judah. Sennacherib, the King of Assyria, sent a messenger to Hezekiah telling him to surrender. Messenger: Sennacherib has ordered me to give you this message. He orders you to surrender, and pay tribute to him, and he will not destroy Judah. He demands 11 tons of silver and 1 ton of gold. If you do not pay his demands, he will destroy you and all of your people. Hezekiah: What choice do I have? I will pay his tribute. Get all of the gold and silver in the kingdom. -

Late Bronze I Period) Apologetic Core, Let Me Make This Important Point Very Clear

By Michael A. Grisanti challenges. (1) Anyone who has worked in archaeology to any degree understands that the collection of data from a dig site is Introduction very scientific and objective, while the interpretation of that data is much more subjective. All archaeologists bring numerous For one who loves biblical studies and is intensely interested presuppositions to their work and that affects what evidence in its intersection with history and archaeology, the potential they emphasize and how they interpret what they find and do impact of the latter on the former deserves attention. In various not find. Consequently, I fully understand that my overview academic and popular settings, numerous scholars in these of various archaeological discoveries below will not satisfy fields make sweeping statements about the disjuncture between everyone. (2) I have chosen certain archaeological discoveries archaeology and/or history and the Bible. Those statements are to make my point, omitting some other very important examples made with authority and have widespread impact, even on an that deserve mention. Not all will agree with my choices for evangelical audience. How do the plain statements of Scripture consideration. (3) I also understand my limitations as a biblical fare when related to what seem to be the objective facts of scholar rather than a trained archaeologist. Regardless, I argue archaeology and history? According to Ron Hendel, below that numerous discoveries made in the last 15–20 years demonstrate that biblical narratives have a “ring of truth” to them Archaeology did not illumine the times and events of when compared with significant and somewhat insignificant Abraham, Moses and Joshua. -

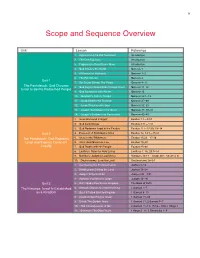

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

Qedem 59, 60, 61 (2020) Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen

QEDEM 59, 60, 61 (2020) AMIHAI MAZAR AND NAVA PANITZ-COHEN Tel Reḥov, A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume I. Introductions, Synthesis and Excavations on the Upper Mound (Qedem 59) (XXIX+415 pp.). ISBN 978-965-92825-0-0 Tel Reḥov, A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume II, The Lower Mound: Area C and the Apiary (Qedem 60) (XVIII+658 pp.). ISBN 978-965-92825-1-7 Tel Reḥov, A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume III, The Lower Mound: Areas D, E, F and G (Qedem 61) (XVIII+465 pp.). ISBN 978-965-92825-2-4 Excavations at Tel Reḥov, carried out from 1997 to 2012 under the direction of Amihai Mazar on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, revealed significant remains from the Early Bronze, Late Bronze and Iron Ages. The most prominent period is Iron Age IIA (10th–9th centuries BCE). The rich and varied architectural remains and finds from this period, including the unique apiary, an open-air sanctuary and an exceptional insula of buildings, make Tel Rehov a key site for understanding this significant period in northern Israel. These three volumes are the first to be published of the five that comprise the final report of the excavations at Tel Rehov. Volume I (Qedem 59) includes chapters on the environment, geology and historical geography of the site, as well as an introduction to the excavation project, a comprehensive overview and synthesis, as well as the stratigraphy and architecture of the excavation areas on the upper mound: Areas A, B and J, accompanied by pottery figures arranged by strata and contexts. -

Strengthening Biblical Historicity Vis-Ã

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Research Publications 9-1-2010 Strengthening Biblical Historicity vis-à-vis Minimalism, 1992-2008, Part 1: Introducing a Bibliographic Essay in Five Parts Lawrence J. Mykytiuk [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_research Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Mykytiuk, Lawrence J., "Strengthening Biblical Historicity vis-à-vis Minimalism, 1992-2008, Part 1: Introducing a Bibliographic Essay in Five Parts" (2010). Libraries Research Publications. Paper 148. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_research/148 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. The following article first appeared in Journal of Religious and Theological Information 9/3–4 (2010): 71–83, which became available online on November 25, 2010. It is used as part of a pilot program enacted November 2011 by the Routledge imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. To link to this article’s Version of Record, click on: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10477845.2010.526920 Strengthening Biblical Historicity vis-à-vis Minimalism, 1992-2008, Part 1: Introducing a Bibliographic Essay in Five Parts LAWRENCE J. MYKYTIUK Purdue University Libraries, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA Abstract This is the first in a series of five articles which cover one aspect of a debate in biblical and ancient Near Eastern studies. In question is the historical reliability of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). Historical/biblical minimalism, the side in the debate which finds the Hebrew Bible almost completely unreliable as a source for history, has already received substantial bibliographic treatment. -

What Did King Josiah Reform?

Chapter 17 What Did King Josiah Reform? Margaret Barker King Josiah changed the religion of Israel in 623 BC. According to the Old Testament account in 2 Kings 23, he removed all manner of idolatrous items from the temple and purified his kingdom of Canaanite practices. Temple vessels made for Baal, Asherah, and the host of heaven were removed, idolatrous priests were deposed, the Asherah itself was taken from the temple and burned, and much more besides. An old law book had been discovered in the temple, and this had prompted the king to bring the religion of his kingdom into line with the requirements of that book (2 Kings 22:8–13; 2 Chronicles 34:14–20).1 There could be only one temple, it stated, and so all other places of sacrificial worship had to be destroyed (Deuteronomy 12:1–5). The law book is easily recognizable as Deuteronomy, and so King Josiah’s purge is usually known as the Deuteronomic reform of the temple. In 598 BC, twenty-five years after the work of Josiah, Jerusalem was attacked by the Babylonians under King Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kings 24:10– 16; 25:1–9); eleven years after the first attack, they returned to destroy the city and the temple (586 BC). Refugees fled south to Egypt, and we read in the book of Jeremiah how they would not accept the prophet’s interpretation of the disaster (Jeremiah 44:16–19). Jeremiah insisted that Jerusalem had fallen because of the sins of her people, but the refugees said it had fallen because of Josiah. -

Archaeology and Religion in Late Bronze Age Canaan

religions Article Archaeology and Religion in Late Bronze Age Canaan Aaron Greener W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem, Salah e-Din St 26, 91190 Jerusalem, Israel; [email protected] Received: 28 February 2019; Accepted: 2 April 2019; Published: 9 April 2019 Abstract: Dozens of temples were excavated in the Canaanite city-states of the Late Bronze Age. These temples were the focal points for the Canaanites’ cultic activities, mainly sacrifices and ceremonial feasting. Numerous poetic and ritual texts from the contemporary city of Ugarit reveal the rich pantheon of Canaanite gods and goddesses which were worshiped by the Canaanites. Archaeological remains of these rites include burnt animal bones and many other cultic items, such as figurines and votive vessels, which were discovered within the temples and sanctuaries. These demonstrate the diverse and receptive character of the Canaanite religion and ritual practices. It seems that the increased Egyptian presence in Canaan towards the end of the period had an influence on the local belief system and rituals in some areas, a fact which is demonstrated by the syncretic architectural plans of several of the temples, as well as by glyptic and votive items. Late Bronze Age religious and cultic practices have attracted much attention from Biblical scholars and researchers of the religion of Ancient Israel who are searching for the similarities and influences between the Late Bronze Age and the following Iron Age. Keywords: Late Bronze Age; Canaan; religion; cult; temples; Egypt 1. Introduction Numerous excavations and a fairly large number of contemporary written documents give us a good picture of the religious system and cult practices in Canaan1 during the Late Bronze Age (ca. -

Israel Exploration Journal Abbreviations

View metadata,citationandsimilarpapersatcore.ac.uk VOLUME 64 • NUMBER 1 • 2014 CONTENTS 1ASSAF YASUR-LANDAU,BOAZ GROSS,YUVAL GADOT,MANFRED OEMING I and ODED LIPSCHITS: A Rare Cypriot Krater of the White Slip II Style from Azekah E Israel 9DAVID T. SUGIMOTO: An Analysis of a Stamp Seal with Complex Religious J Motifs Excavated at Tel ªEn Gev 22 RAZ KLETTER: Vessels and Measures: The Biblical Liquid Capacity System 38 SHLOMIT WEKSLER-BDOLAH: The Foundation of Aelia Capitolina in Light of New Excavations along the Eastern Cardo Exploration 63 RONNY REICH and MARCELA ZAPATA MEZA: A Preliminary Report on the Miqwaºot of Migdal 72 RABEI G. K HAMISY: The Treaty of 1283 between Sultan Qalâwûn and the Frankish Authorities of Acre: A New Topographical Discussion 103 ALEXANDER GLICK,MICHAEL E. STONE and ABRAHAM TERIAN:An Armenian Inscription from Jaffa Journal 119 NOTES AND NEWS 121 REVIEWS 126 BOOKS RECEIVED — 2013 Page layout by Avraham Pladot Typesetting by Marzel A.S. — Jerusalem 64 VOLUME 64 • NUMBER 1 Printed by Old City Press, Jerusalem provided by 1 JERUSALEM, ISRAEL • 2014 Helsingin yliopistondigitaalinenarkisto brought toyouby CORE ISRAEL EXPLORATION JOURNAL ABBREVIATIONS AASOR Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research ADAJ Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan Published twice yearly by the Israel Exploration Society and the Institute of AJA American Journal of Archaeology Archaeology of the Hebrew University, with the assistance of the Nathan AfO Archiv für Orientforschung Davidson Publication Fund in Archaeology, Samis Foundation, Seattle WA, ANET Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament3, ed. J.B. Pritchard, and Dorot Foundation, Providence RI Princeton, 1969 BA The Biblical Archaeologist BASOR Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research Founders BT Babylonian Talmud A. -

Notes on 2 Kings 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on 2 Kings 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Second Kings continues the narrative begun in 1 Kings. It opens with the translation of godly Elijah to heaven and closes with the transportation of the ungodly Jews to Babylon. For discussion of title, writer, date, scope, purpose, genre, style, and theology of 2 Kings, see the introductory section in my notes on 1 Kings. OUTLINE (Continued from notes on 1 Kings) 3. Ahaziah's evil reign in Israel 1 Kings 22:51—2 Kings 1:18 (continued) 4. Jehoram's evil reign in Israel 2:1—8:15 5. Jehoram's evil reign in Judah 8:16-24 6. Ahaziah's evil reign in Judah 8:25—9:29 C. The second period of antagonism 9:30—17:41 1. Jehu's evil reign in Israel 9:30—10:36 2. Athaliah's evil reign in Judah 11:1-20 3. Jehoash's good reign in Judah 11:21—12:21 4. Jehoahaz's evil reign in Israel 13:1-9 5. Jehoash's evil reign in Israel 13:10-25 6. Amaziah's good reign in Judah 14:1-22 7. Jeroboam II's evil reign in Israel 14:23-29 8. Azariah's good reign in Judah 15:1-7 9. Zechariah's evil reign in Israel 15:8-12 10. Shallum's evil reign in Israel 15:13-16 11. Menahem's evil reign in Israel 15:17-22 12. Pekahiah's evil reign in Israel 15:23-26 13. Pekah's evil reign in Israel 15:27-31 Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L.