Volume 4, Issue 1 | 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 12, 2002 Issue

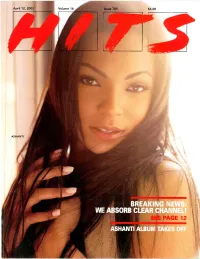

April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue '89 $6.00 ASHANTI IF it COMES FROM the HEART, THENyouKNOW that IT'S TRUE... theCOLORofLOVE "The guys went back to the formula that works...with Babyface producing it and the greatest voices in music behind it ...it's a smash..." Cat Thomas KLUC/Las Vegas "Vintage Boyz II Men, you can't sleep on it...a no brainer sound that always works...Babyface and Boyz II Men a perfect combination..." Byron Kennedy KSFM/Sacramento "Boyz II Men is definitely bringin that `Boyz II Men' flava back...Gonna break through like a monster!" Eman KPWR/Los Angeles PRODUCED by BABYFACE XN SII - fur Sao 1 III\ \\Es.It iti viNA! ARM&SNykx,aristo.coni421111211.1.ta Itccoi ds. loc., a unit of RIG Foicrtainlocni. 1i -r by Q \Mil I April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 789 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher ISLAND HOPPING LENNY BEER Editor In Chief No man is an Island, but this woman is more than up to the task. TONI PROFERA Island President Julie Greenwald has been working with IDJ ruler Executive Editor Lyor Cohen so long, the two have become a tag team. This week, KAREN GLAUBER they've pinned the charts with the #1 debut of Ashanti's self -titled bow, President, HITS Magazine three other IDJ titles in the Top 10 (0 Brother, Ludcaris and Jay-Z/R. TODD HENSLEY President, HITS Online Ventures Kelly), and two more in the Top 20 (Nickelback and Ja Rule). Now all she has to do is live down this HITS Contents appearance. -

Songwriter Mike O'reilly

Interviews with: Melissa Sherman Lynn Russwurm Mike O’Reilly, Are You A Bluegrass Songwriter? Volume 8 Issue 3 July 2014 www.bluegrasscanada.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS BMAC EXECUTIVE President’s Message 1 President Denis 705-776-7754 Chadbourn Editor’s Message 2 Vice Dave Porter 613-721-0535 Canadian Songwriters/US Bands 3 President Interview with Lynn Russworm 13 Secretary Leann Music on the East Coast by Jerry Murphy 16 Chadbourn Ode To Bill Monroe 17 Treasurer Rolly Aucoin 905-635-1818 Open Mike 18 Interview with Mike O’Reilly 19 Interview with Melissa Sherman 21 Songwriting Rant 24 Music “Biz” by Gary Hubbard 25 DIRECTORS Political Correctness Rant - Bob Cherry 26 R.I.P. John Renne 27 Elaine Bouchard (MOBS) Organizational Member Listing 29 Gord Devries 519-668-0418 Advertising Rates 30 Murray Hale 705-472-2217 Mike Kirley 519-613-4975 Sue Malcom 604-215-276 Wilson Moore 902-667-9629 Jerry Murphy 902-883-7189 Advertising Manager: BMAC has an immediate requirement for a volunteer to help us to contact and present advertising op- portunities to potential clients. The job would entail approximately 5 hours per month and would consist of compiling a list of potential clients from among the bluegrass community, such as event-producers, bluegrass businesses, music stores, radio stations, bluegrass bands, music manufacturers and other interested parties. You would then set up a systematic and organized methodology for making contact and presenting the BMAC program. Please contact Mike Kirley or Gord Devries if you are interested in becoming part of the team. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Call us or visit our website Martha white brand is due to the www.bluegrassmusic.ca. -

Lennie Petze Profile

LENNIE PETZE A SENIOR LEVEL, RECORD COMPANY EXECUTIVE WITH OVER 50 YEARS EXPERIENCE IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. SPECIALIZING IN THE ARTIST & REPERTOIRE FIELD WITH OVER 100 GOLD, PLATINUM AND MULTI-PLATINUM AWARDS FOR RECORDING ARTISTS SIGNED AND RECORDS PRODUCED WITH SALES OF OVER 150 MILLION UNITS. SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE DISCOVERY OF CYNDI LAUPER AND BOSTON. The Early Years: It's a Friday night in early 1957. Fourteen year old Lennie Petze was excited to be at what was his first high school dance, "A Record Hop." A Disc Jockey was playing the hit 45's of the day. The sound was loud and bouncing off the wooden walls in the Weymouth Massachusetts High School gymnasium. A new sound of guitars, drums, pumping bass and vocals bred energy for all the teenagers anxious to dance, to a sound created by "Rock and Roll" The DJ replayed "Party Doll" by Buddy Knox five times in three hours! He also played "Poor Butterfly" by Charlie Gracie, "Roll Over Beethoven" by Chuck Berry, "Eddie My Love" by The Teen Queens and "I'm Sticking With You" by Jimmy Bowen. Lennie had heard all these songs on Boston radio, but this environment added another dimension of excitement. One that left him longing to create that environment for himself and become a bigger part of it. It was this experience that lead to experimenting with the formation of bands. Teens from the suburbs of Boston, Massachusetts; Weymouth, Quincy and Braintree that called themselves "The Rhythm Rockers", "The Rainbows"", and The Reveleers" kicking off a hugely successful music career lasting over 50 years. -

Know Personally, Live Passionately 1St Edition Free Download

FREE THE CALL; KNOW PERSONALLY, LIVE PASSIONATELY 1ST EDITION PDF Ben Gutierrez | 9781600364815 | | | | | | First Edition Books The The Call; Know Personally could have evaporated after releasing just those two titles and would have been revered as pop maestros; both compositions are not what one would expect from exiles of the New Christy Minstrels. This album puts it into perspective with the seven Top 40 hits the group accrued between andas well as "Love Woman," "Momma's Waiting," and the Mac Davis title "I Believe in Music," which Gallery hit with and which was covered by many others, including Helen Reddy. It's not chronological, and opening up Live Passionately 1st edition "Ruby, Don't Take Your Love to Town" as Rogers does with his solo greatest hits package, Ten Years of Gold is probably more of a personal decision. The sizzling guitars on the neo-hard rock "Just Dropped In" are relegated to the middle of the disc, though a Mick Jagger would have opened the album up with his "always hit 'em hard at first" mindset. But regardless of the tracking, the First Edition truly is a band that racked up an impressive array of hits which do not get their fair share of play on classic rock stations, some major oldies stations also neglecting what is an Live Passionately 1st edition body of work. Kenny Rogers ' career and fame in country and pop music eradicated the value of this group on the live circuit, something many of its contemporaries embraced. Sad to say, a reunion of the First Edition would not get the response it deserves,as those who want to hear this material do so when Kenny Rogers comes to town. -

“Amarillo by Morning” the Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1

In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. On Billboard magazine’s April 4, 1964, Hot 100 2 list, the “Fab Four” held the top five positions. 28 One notch down at Number 6 was “Suspicion,” 29 by a virtually unknown singer from Amarillo, Texas, named Terry Stafford. The following week “Suspicion” – a song that sounded suspiciously like Elvis Presley using an alias – moved up to Number 3, wedged in between the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout” and “She Loves You.”3 The saga of how a Texas boy met the British Invasion head-on, achieving almost overnight success and a Top-10 hit, is one of triumph and “Amarillo By Morning” disappointment, a reminder of the vagaries The Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1 that are a fact of life when pursuing a career in Joe W. Specht music. It is also the story of Stafford’s continuing development as a gifted songwriter, a fact too often overlooked when assessing his career. Terry Stafford publicity photo circa 1964. Courtesy Joe W. Specht. In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. -

Experiencing Film Music a Listcb 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

EXPERIENCING FILM MUSIC A LISTCB 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kenneth LaFave | 9781442258419 | | | | | Experiencing Film Music A Listcb 1st edition PDF Book My students requested examples of the each of the functions. Thelma also recorded in Europe under the name Tess Ivie the latter being her husband's last name. Alternate the Perception of Time The perception of time is a fantastic playground for music. Notify me of follow-up comments by email. Slowly growing apart from the others, Camacho began to feel restricted by the band in a number of ways. Michael A Levine on December at Robin on 9. In this scene the music unites the characters in the movie as well as the audience:. At Rogers' shows the song was often clapped along to, or joked around with, but it was meant seriously at the time. He later switched to a more teen-oriented bubblegum sound that their manager Ken Kragen felt would appeal to his fans. A program of well-crafted supplementary materials continues to serve the needs of students as well as instructors using the text. I feel that music deters from rather than adds to TV or films. Kenny disagreed, wanting a more conservative agenda. The group increasingly played on the county fair circuit. She moved to Europe in the s and lost contact with the rest of the group until Thank you for posting this content! In , with the help of Terry Williams' mother, who worked for producer and executive Jimmy Bowen , they signed with Reprise and recorded their first single together, "I Found a Reason", which had minor sales. -

Buddy Knox & Jimmy Bowen

Buddy Knox Buddy Knox & Jimmy Bowen mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Buddy Knox & Jimmy Bowen Country: Canada Style: Rockabilly MP3 version RAR size: 1508 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1221 mb WMA version RAR size: 1287 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 742 Other Formats: APE ADX ASF WAV MP1 XM APE Tracklist A1 –Buddy Knox That's Why I Cry A2 –Buddy Knox Teasable, Pleasable You A3 –Buddy Knox Somebody Touched Me A4 –Buddy Knox All For You A5 –Buddy Knox C"mon Baby A6 –Buddy Knox The Girl With The Golden Hair B1 –Jimmy Bowen By The Light Of The Silvery Moon B2 –Jimmy Bowen My Kind Of Woman B3 –Jimmy Bowen Blue Moon B4 –Jimmy Bowen Stick With Me B5 –Jimmy Bowen Whenever I'm Lonely B6 –Jimmy Bowen Two-Step Credits Photography By [Cover] – Alfred Gescheidt Producer – Hugo & Luigi Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Buddy Knox Buddy Knox & Jimmy R-25048 & Jimmy Bowen - Buddy Knox & Roulette R-25048 US 1959 Bowen Jimmy Bowen (LP) Buddy Knox Buddy Knox & Jimmy R-25048 & Jimmy Bowen - Buddy Knox & Roulette R-25048 Canada 1959 Bowen Jimmy Bowen (LP) Buddy Knox & Jimmy Buddy Knox Bowen - Buddy Knox & South R-25048 & Jimmy Roulette R-25048 1959 Jimmy Bowen (LP, Africa Bowen Album) Buddy Knox & Jimmy Buddy Knox RR-25048, Bowen - Buddy Knox & Roulette, RR-25048, & Jimmy Canada Unknown R-25048 Jimmy Bowen (LP, Roulette R-25048 Bowen Mono) Buddy Knox & Jimmy Buddy Knox Bowen - Buddy Knox & R-25048 & Jimmy Roulette R-25048 US 1959 Jimmy Bowen (LP, Bowen Album) Related Music albums to Buddy Knox & Jimmy Bowen by Buddy Knox Buddy Knox - Lovey Dovey Jimmy Bowen With The Rhythm Orchids - Somebody Touched Me / C'Mon Baby Lieutenant Buddy Knox With The Rhythm Orchids - Rock Your Little Baby To Sleep / Don't Make Me Cry Jimmy Bowen With The Rhythm Orchids - Warm Up To Me Baby / I Trusted You Buddy Knox - Buddy Knox Buddy Knox - Party Doll / Rock Your Little Baby To Sleep Buddy Knox - God Knows I Love You Buddy Knox With The Rhythm Orchids - Swingin' Daddy / Whenever I'm Lonely Jimmy Bowen With Hugo Peretti & His Orch. -

12-17-20 Rockabilly Auction Ad

John Tefteller’s World’s Rarest Records Address: P. O. Box 1727, Grants Pass, OR 97528-0200 USA Phone: (541) 476–1326 or (800) 955–1326 • FAX: (541) 476–3523 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.tefteller.com Auction closes Thursday, December 17, 2020 at 7:00 p.m. PT See #33 See #44 Original 1950’s Rockabilly / Country Boppers / Teen Rockers 45’s Auction 1. The Anderson Sisters — “The Wolf 17. Boyd Bennett — “The Brain/Coffee 31. Gene Brown — “Big Door/Playing 43. Johnny Burnette — “Me And The Hop/Empty Arms And A Broken Break” MERCURY 71813 M- WHITE With My Heart” 4 STAR 1717 MINT Bear/Gumbo” FREEDOM 44011 M- Heart” FORTUNE 202 (SEE INSERT LABEL PROMO MB $20 FIrst label, true first pressing before it WHITE LABEL PROMO with date of 4/2/59 BELOW) 18. Rod Bernard — “Pardon, Mr. Gordon/ went nationwide on Dot MB $30 written neatly on the label MB $20 2. Angie & The Citations — “I Wanna This Should Go On Forever” ARGO 32. Gene Brown — “Big Door/Playing 44. Mel Calvin And The Kokonuts — Dance/Salt & Pepper” ANGELA NO # 5327 M- MB $20 With My Heart Again” DOT 15709 “My Mummy/I Love You” BERTRAM VG Wol and slight storage warp with NO 19. Bob And The Rockbillies — “Your M- MB $20 INTERNATIONAL 215 M- MB $50 effect on play. Super obscure one from Kind Of Love/Baby Why Did You Have 33. Tom Brown And The Tom Toms — (See picture at top of page) Tamaqua, Pennsylvania MB $20 To Go” BLUE-CHIP 011 M- TWO- “Kentucky Waltz/Tomahawk” JARO 45. -

Johnny Rivers

Johnny Rivers... Chart Hits Include: * 17 Gold records * 29 chart hits * Two Grammy Awards, Memphis * Sold more than 30 million records * In 2006, the Maybelline singer/songwriter/producer continues to perform before sell- Mountain of Love out crowds worldwide. *The “Secret Agent Man” has many other accomplishments and has made significant Midnight Special contributions to the history of rock ‘n roll. Seventh Son Where Have All the Flowers Gone • Born in New York City, grew up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Secret Agent Man • Began playing professionally at age 14 when he formed his first band, Poor Side of Town “Johnny and The Spades.” Baby, I Need Your Lovin’ • Recorded his first single 1957 for Suede Records of Natchez, MS, at Tracks of My Tears Cosmos Studios in New Orleans. “Hey Little Girl” became a regional Summer Rain chart hit. Look to Your Soul • In late 1957 at age 15, Johnny Ramistella went back to New York City Rockin’ Pneumonia – Boogie Woogie Flu where he met the legendary D.J. Alan Freed, who got him a record deal Sea Cruise with Gone Records and changed his last name to Rivers. Blue Suede Shoes • In 1958, while performing on the “Louisiana Hayride” in Shreveport, LA, Help Me Rhonda Rivers was introduced to Ricky Nelson’s guitar player James Burton, who Slow Dancin’ took a song Rivers wrote, “I’ll Make Believe,” back to Hollywood and played it for Nelson who recorded it. Rivers hopped a plane from New Curious Mind Orleans to Los Angeles where he hooked up with Burton, met Ricky Nelson and struck up a friendship. -

|||GET||| Hindi Film Songs and the Cinema 1St Edition

HINDI FILM SONGS AND THE CINEMA 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Anna Morcom | 9781351563741 | | | | | Rare & Collectible Books Khatija Rahman: There is nothing wrong in wanting to work in the field that your parents are in. In publishing terms, a first edition book is all copies that were printed from the same setting of type as when first published. The event, which took place at Bandra-Kurla Complex, saw around to pregnant women participating in the first edition of pregathon. It was a one of a kind event wherein pregnant women pledged to stay fit and celebrate the beautiful journey that is motherhood. Read more articles Most expensive sales from January to March, AbeBooks' list of the most expensive sales in January, February and March includes a massive book, Alice, Bond and more. The First Edition never got the respect it richly deserved and this album with its wonderful Jimmy Bowen and Mike Post production work is important and still fun to listen to. Madhuri Dixit Nene lauds Assamese doctor for his moonwa The duo is currently Hindi Film Songs and the Cinema 1st edition their vacation in the US and they have been posting a lot of beautiful pictures and videos on their respective Instagram handles. Lorenzo stayed for roughly six months. A drama about the music biz, they played the group Catweazel. Today, he shared a sweet throwback video of his mother Sutapa Sikdar and Irrfan from the streets of London. Settle had first come up with the idea of forming the band as his work took on the characteristics of rock. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Year, Song of the Year, Breakthrough Artist of the Year, Breakthrough Songwriter, and Breakthrough Artist- Category 1: Producer of the Year

PRESENTED BY: 32ND ANNUAL MusicRow Subscribed Members will vote to determine award winners. Ballots will be emailed on July 8, 2020. Ballot Voting Period: July 8, 2020 at 11:00 a.m. CST – July 17, 2020 at 5:00 p.m. CST. Winners Announced: August 18, 2020 To become a member, click here. Pictured: Alecia Davis, Kathie Lee Gifford, Sherod Robertson on stage at the 2019 MusicRow Awards. Photo: Steve Lowry By Sarah Skates MusicRow Magazine is proud to reveal the nominees for outside nominations being considered for Breakthrough the 2020 MusicRow Awards. This year’s honors will be Songwriter and Breakthrough Artist-Writer. Male and announced virtually among multiple MusicRow platforms Female Songwriter nominees are based on data from on Tuesday, August 18, 2020. MusicRow’s Top Songwriter Chart. Eligible projects were active between April 1, 2019 to May 31, 2020. Now in its 32nd year, the MusicRow Awards are Nashville’s longest-running music industry trade publication honors. In addition to established awards for Producer of the TABLE OF CONTENTS Year, Song of the Year, Breakthrough Artist of the Year, Breakthrough Songwriter, and Breakthrough Artist- Category 1: Producer of the Year .........................................................4 Writer; the MusicRow Awards expanded with the Category 2: Label of the Year ...............................................................8 additional categories Label of the Year, Talent Agency Category 3: Talent Agency of the Year ..............................................10 of the Year, Robert K. Oermann Discovery Artist of the Category 4: Breakthrough Songwriter of the Year .........................13 Year, Male and Female Songwriters of the Year, and Artist Category 5: Breakthrough Artist-Writer of the Year .......................19 of the Year in 2019. -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Various TITLE Four Legends Of Rock ‘n’ Roll LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BCD 17328 PRICE-CODE AH EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy173288z FORMAT 1 CD digipac with booklet GENRE Rock ‘n’ Roll TRACKS 30 PLAYING TIME 87:38 G One of the most amazing Rockabilly and Rock 'n' Roll shows of all times! G Four of the greatest stars, on one stage! G Finally, this great live show is available on CD! G Eight songs previously unissued! G Booklet contains extensive liner notes, written by Ian Wallis a.o. G Booklet also contains many rare photos of the show INFORMATION It all seemed so unlikely when the news came of the 'Sun Sound Show' to be held at North London's Rainbow Theatre starring Buddy Knox, Charlie Feathers, Warren Smith and Jack Scott. Despite two of the artists having no connection with SUN RECORDS this was truly a dream line up. But would it, could it really happen? The questions were answered on April 30th 1977 when a near full house gathered for what was to prove an epic night of Rockabilly and Rock 'n' Roll. The atmosphere was electric and the anti- cipation high. Buddy Knox had already become familiar through his earlier visits to the U.K but there was some surprise at his appearance when he took to the stage, his permed hair do and flared trousers being at odds with most of the audience.