The Weighing of Daleville/Annie Dillard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natasha Bedingfield Leaves It Unwritten

20/20 BY CHERYLZHANG Natasha Bedingfi eld leaves it unwritten Leaving it ‘Unwritten’ has defi nitely gotten her name written down in the Billboard charts for Natasha Bedingfi eld. Since the overwhelming success of the album, which sold over 2.3 million copies worldwide, Natasha Bedingfi eld has been hard at work, releasing a second album in April 2007 entitled ‘N.B.’ (no, it’s not some dialect vulgarity, it’s her initials you foul-minded people). I’M A BOMB to be a bit more tough and I feel like I defi nitely have noticed a Bedingfi eld isn’t any prima donna who demands Perrier and red diff erence in myself when I’m in other countries and I feel more at carpets to be rolled out. In fact, she’s exactly like any other reader home when I’m here [in London].” of Choices! Currently dating someone whose identity she refuses “I love going to clubs and I love music that you can dance to. to reveal, Bedingfi eld had been incorrectly linked to several You know I put on the Justin Timberlake album at my birthday a celebrities such as Nick Lachey and Maroon 5 lead singer Adam few months ago and I hadn’t realised what a great album it was Levine. until it was actually like a party and I put it on and me and all my girlfriends were dancing in the kitchen (laughing). It was great, STARTING OUT it was actually… it just had a really good beat to dance to. And Despite being extremely proud of her British heritage, Bedingfi eld that’s the thing about music is that you’ve got to have something has spent most of the past 18 months in America, and lets us in for everything, and you need the music you can chill out to or on the reason why. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

The Best Teen Writing of 2013

The SCholastic Art & Writing AwardS PReSents The Best TeeN writing of 2013 The scHoLastic art & Writing Awards presents The Best teen Writing Edited by Loretta López of 2010 Scholastic Awards 2013 Gold Medal Portfolio Recipient Foreword by terrance Hayes 2010 National Book Award Recipient in Poetry dedication The Best Teen Writing of 2013 is dedicated to the extraordi- nary team at Scholastic Inc. Corporate Communications and Media Relations: Kyle Good, Cathy Lasiewicz, Morgan Baden, Anne Sparkman, and Lia Zneimer. Their genuine dedication to the students and appreciation for the students’ work shines For information or permission, contact: through in everything they do for the Awards and the Alliance Alliance for Young Artists & Writers for Young Artists & Writers. By raising awareness of the pro- 557 Broadway gram in national and local media, the team is instrumental New York, NY 10012 in both giving students access to scholarships and helping the www.artandwriting.org Scholastic Art & Writing Awards fulfill its mission. This committed team works tirelessly to promote the Scho- No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or lastic Art & Writing Awards. Its many contributions include in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in highlighting students in their hometown newspapers and other any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, local media outlets, approaching national media with trends photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without and themes among Award winners for feature articles, high- written permission from the publisher. lighting the National Student Poet Program, spreading the word about Scholastic Awards ceremonies and exhibitions on Editor: Loretta López events pages in print and online, and promoting the visibility Senior Manager, Programs: Scott Larner of the Awards through social media. -

1Q12 IPG Cable Nets.Xlsm

Independent Programming means a telecast on a Comcast or Total Hours of Independent Programming NBCUniversal network that was produced by an entity Aired During the First Quarter 2012 unaffiliated with Comcast and/or NBCUniversal. Each independent program or series listed has been classified as new or continuing. 2061:30:00 Continuing Independent Series and Programming means series (HH:MM:SS) and programming that began prior to January 18, 2011 but ends on or after January 18, 2011. New Independent Series and Programming means series and programming renewed or picked up on or after January 18, 2011 or that were not on the network prior to January 18, INDEPENDENT PROGRAMMING Independent Programming Report Chiller First Quarter 2012 Network Program Name Episode Name Initial (I) or New (N) or Primary (P) or Program Description Air Date Start Time* End Time* Length Repeat (R)? Continuing (C)? Multicast (M)? (MM/DD/YYYY) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 01:00:00 02:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 02:30:00 04:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 08:00:00 09:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 09:30:00 11:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 11:00:00 12:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The Outlaws of the Marsh

The Outlaws of the Marsh Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong The Outlaws of the Marsh Table of Contents The Outlaws of the Marsh..................................................................................................................................1 Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Zhang the Divine Teacher Prays to Dispel a Plague Marshal Hong Releases Demons by Mistake....................................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 Arms Instructor Wang Goes Secretly to Yanan Prefecture Nine Dragons Shi Jin Wreaks Havoc in Shi Family Village...................................................................................................15 Chapter 3 Master Shi Leaves Huayin County at Night Major Lu Pummels the Lord of the West.......32 Chapter 4 Sagacious Lu Puts Mount Wutai in an Uproar Squire Zhao Repairs Wenshu Monastery....42 Chapter 5 Drunk, the Little King Raises the Gold−Spangled Bed Curtains Lu the Tattooed Monk Throws Peach Blossom Village into Confusion...................................................................................57 Chapter 6 Nine Dragons Shi Jin Robs in Red Pine Forest Sagacious Lu Burns Down Waguan Monastery.............................................................................................................................................67 Chapter 7 The Tattooed Monk Uproots a Willow -

Paradise Lost : 11Th Doctor Audio Original Darren Jones Pub Date

BBC PHYSICAL AUDIO BBC Physical Audio Doctor Who: Paradise Lost : 11th Doctor Summary: An original adventure for the Eleventh Doctor Audio Original and Clara, exclusive to audio. Darren Jones Pub Date: 8/1/20 $18.95 USD 1 pages Firefly Books Escape from Syria Summary: "Groundbreaking and unforgettable." Samya Kullab, Jackie Roche --Kirkus (starred review) Pub Date: 8/1/20 $9.95 USD "This is a powerful, eye-opening graphic novel that will 96 pages foster empathy and understanding in readers of all ages." --The Globe and Mail "In league with Art Spiegelman's Maus and Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis, this is a must-purchase for any teen or adult graphic novel collection." --School Library Journal (starred review) From the pen of former Daily Star (Lebanon) reporter Samya Kullab comes this breathtaking and hard-hitting story Stone Arch Books Wonder Woman and The Cheetah Challenge Summary: When chaos erupts at the Global Village theme Laurie S. Sutton, Leonel Castellani park, Wonder Woman swoops in to find her archenemy on Pub Date: 8/1/20 the loose! The Cheetah has stolen a golden statue from the $6.95 USD Mayan exhibit and seems bent on causing mayhem. After a 72 pages tense standoff, a cat-and-mouse chase ensues, until the villain challenges Wonder Woman to a showdown in the Greek showcase. Can the Amazon warrior subdue her foe before the feline felon reduces the theme park to ruin? Find out in this action-packed chapter book for DC Super Hero fans. Stone Arch Books The Flash and the Storm of the Century Summary: A storm is brewing in Central City! The Weather Michael Anthony Steele, Gregg Schigiel Wizard has unleashed the fury of his giant weather wand in Pub Date: 8/1/20 a bid to get the city's citizens to cough up their cash. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Davie Lloyd out As Weems CEO George Island There Will Be a Community by David Adlerstein Ficer

Crazy for geocaching, A10 Thursday, November 24, 2011 WWW.APALACHTIMES.COM Vol. 126 IssUE 30 50¢ xxxxxOut to see Thanksgiving on St. Davie Lloyd out as Weems CEO George Island There will be a community By David Adlerstein ficer. of Lloyd’s initial perfor- cussions with TMH of- Thanksgiving lunch at 12:30 Times City Editor Lloyd, 39, was hired in mance, said she was noti- ficials since last month’s p.m. at the St. George Island July, at an annual salary fied last week of Lloyd’s county commission meet- United Methodist Church, Davie Lloyd has left of $145,000, to succeed departure. ing, when she agreed to 201 E. Gulf Beach Drive. her position as hospital Weems CEO Chuck Col- Sanders had asked amend her motion for Turkey and ham provided, CEO, although officials vert. She most recently for Lloyd’s removal dur- Lloyd’s removal so as to bring covered dish. There at Weems Memorial Hos- served as CEO of Flem- ing the commissioners’ grant TMH until Jan. 3, will also be a community pital are not confirming ing County Hospital, a 52- Oct. 18 questioning of 2012, to satisfy the com- Thanksgiving dinner at Eddy whether she was removed bed not-for-profit county Mark O’Bryant, CEO of missioners’ concerns Teach’s Raw Bar at 4 p.m. or voluntarily stepped hospital in Flemingsburg, Tallahassee Memorial about Lloyd’s perfor- Bring covered dish or dessert down. Ky., that was managed HealthCare. TMH has an mance. if you can. Band begins Staff at the hospital at that time by Quorum affiliation agreement with TMH said it plans to around 7 p.m. -

A Carol's Christmas

A CAROL’S CHRISTMAS BY TINA PISCO A CAROL’S CHRISTMAS IN P RO S E BEING A GHOST STORY OF CHRISTMAS by Tina Pisco First published by Fish Publishing, 2016 Durrus, Bantry, Co. Cork. in Sunrise Sunset and other fictions Copyright © Tina Pisco ISBN 978-0-9562721-9-5 A Carol’s Christmas STAVE ONE MARLA’S GHOST “Marley was dead: to begin with. There was no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it: and Scrooge’s name was good upon ’Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was dead as a doornail.” What a load of bullshit, thought Carol as she closed the book and put it back on the pile of unwrapped presents on her desk. How the hell was she meant to get her kids to read a book if Charles Dickens couldn’t write a more attention grabbing first paragraph. He would never have made it in television. It was a handsome volume, bound in red leather with: “Children’s Classics: A Christmas Carol” embossed in gold. Very posh, very educational. It would look well on the bookshelf, even if nobody ever read it. It was one of those last minute stocking-filler impulse buys that she forgot about almost immediately after she’d swiped her credit card. When the bills came in January she could never remember why the hell she thought whatever she’d bought was so wonderful just a month earlier. -

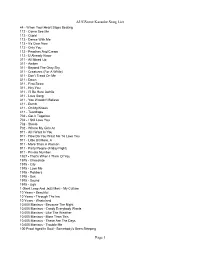

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

The Science of Sound/Audio

22 - The Science of Sound/Audio . Leveraging Sound Branding Posted on August 22, 2013 by admin ―I should have known, sound branding! Sound Branding is common sense. Quite simply, we are wired to go. It is said that the human ear reacts to certain sounds more than others. This is sound branding. Sound, most notably music, triggers emotions, auditory pleasures, memories and associations. Sound branding is a multi-sensory form of communication and a holistic corporate model, which drives perception. It also creates attention with familiar associations. It also differentiates from the dross of typical advertising media. The benefit of this auditory effect is that it enhances brand identity, loyalty, and thus increases sales. Take the memorable Intel or Coca-Cola jingles as key examples. Harley Davidson‘s distinctive and trademarked motorcycle exhaust sound, and Kellogg‘s investment in the power of auditory stimulus with its cereal crunching demonstrates strategic marketing through sound branding. Firms of this sort understand sound branding delivers personality. The advent of digital media and devices increases the communication of the sound branding experience. Sampling of sound branding through audio identity should be appreciated by listening to the following examples:can be viewed and heard here. • Bentley Motor Cars developed ―The new sound of Bentley‖ — a stirring and thunderous soundtrack and the prelude to a potent new Bentley driving experience. • Hip boutique hotels such as Puro Hotel in Mallorca, whose beach bar has been voted one of the world‘s 50 best by CNN Travel, surrounds you everywhere with lounge/chill-out genre of music compiled by its in-house DJ ‒ whether you open their website, choose to listen to their on-line steaming player, purchase a CD, relax by the pool sipping a passion fruit mojito or come nightfall, gather around to dance to their house tunes.