Building a Collection of Contemporary Art in Africa: Interview with Collector Sindika Dokolo by Shannon Fitzgerald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bili Bidjocka. the Last Supper • Simon Njami, Bili Bidjocka

SOMMAIRE OFF DE DAPPER Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau ............................................................................. 6 SOLY CISSÉ. Lecture d’œuvre/Salimata Diop ................................................................................... 13 ERNEST BRELEUR. Nos pas cherchent encore l’heure rouge/Michael Roch ...................................................... 19 Exposition : OFF de Dapper Fondation Dapper 5 mai - 3 juin 2018 JOËL MPAH DOOH. Commissaire : Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau Transparences/Simon Njami ....................................................................................... 25 Commissaire associée : Marème Malong Ouvrage édité sous la direction de Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau BILI BIDJOCKA. Contribution éditoriale : Nathalie Meyer The Last Supper/Simon Njami ................................................................................... 29 Conception graphique : Anne-Cécile Bobin JOANA CHOUMALI. Série « Nappy ! »/Olympe Lemut ................................................................................. 33 BEAUGRAFF & GUISO. L’art de peindre les maux de la société/Ibrahima Aliou Sow .......................................... 39 GABRIEL KEMZO MALOU. Le talent engagé d’un homme libre/Rose Samb ............................................................... 45 BIOGRAPHIES DES ARTISTES...................................................................... 50 BIOGRAPHIES DES AUTEURS...................................................................... 64 CAHIER PHOTOGRAPHIQUE. MONTAGE -

DAK'art 2016 BIENNALE of DAKAR May, 3

DAK’ART 2016 BIENNALE of DAKAR May, 3 – June, 2 — 2016 12th Edition of the Dakar Biennale « The City in the Blue Daylight » Simon Njami, Artistic Director PRESS RELEASE CONTENT 1. What Is Dak’art 2. The City In The Blue Daylight 3. Who’s Simon Njami 4. The Program of Dak’art 2016 5. Participating artists 6. Contact 1. WHAT IS DAK’ART Dak’Art, The Dakar Biennale, is the first and the major international Art event dedicated to the Contemporary African creation. Initiated in 1996 by the Republic of Senegal, the biennale is organized by the Ministry of Culture and Communication. Its 12th edition will take place from May 3, to July 11, 2016. The aims of Dak’Art are to offer the African artists a chance to show their work to a large and international audience, and to elaborate a dis- course in esthetic, by participating to the conceptualization of theorical tools for analyse and appropriation of the global art world. Mahmadou Rassoul Seydi is the General Secretary of Dak’Art. Simon Njami, writer and independant curator, is the Artistic Director of the 12th Edition of the Dakar Biennale. As a departure for Dak’Art 2016, with the title « The City in the Blue Daylight », Simon Njami chose an extract from a poem written by Leopold Sedar Senghor : « Your voice tells us about the Republic that we shall erect the City in the Blue Daylight In the equality of sister nations. And we, we answer: Presents, Ô Guélowâr ! » Those verses inspire Simon Njami’s ambition for the Biennale : to make Dak’Art a « new Bandung for Culture ». -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Table of Content

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Table of content Letter from the Executive Director 4 Lettera27 Our mission 7 Initiatives in 2015 8 Strategic Plan 9 Activities Activities map 12 AtWork 14 Ashoka Changemaker Schools 26 Sustain-Ability 28 Why Africa? 30 Focus on migrants 32 Ecriture Infinie/Infinite Writing Book 9 34 OSF partnership 36 The notebooks collection 38 Various events and initiatives 40 Summary 42 The 2015 was a significant year for lettera27. We have learned a lot of new things and tested our purpose in the areas that we always pursue: innovative informal educational practices, art and culture for social transformation, sustainable culture. While implementing AtWork format in various countries and contexts, we have paid close attention to the suggestions and thoughts Letter from the Executive Director of our partners regarding the proposed format themes, as well as reactions of the participants. Letter from the Executive Director Strong, determined and profound thoughts. We have shared them and debated them, since we deal with critical thinking and we hope to build a new generation of thinkers. Utopia? Yes, a concrete one, paraphrasing Ou Ning who has been facilitating our AtWork workshop at Polimoda in Florence. But also Heterotopia, a topic proposed by Simon Njami for students of Fondazione Fotografia in Modena. And if it was “Something Else? …another paradigm, proposed at Cairo? So We have nothing to teach to many questions… “Why?”, provokes “Why Africa?”, our editorial column of Doppiozero. And various forms of responses to this question. I’m anyone […] This inner light that talking about forms, as the questions are not only verbal, or definitive, or univocal. -

Bill Bidjocka

Goodman Gallery Bill Bidjocka Biography Bili Bidjocka was born in Douala, Cameroon, in 1962, but lived in Paris from the age of twelve. Nowadays, he moves between Paris, Brussels, and New York. Though he says of himself that he is a painter not a writer, Bidjocka acknowledges that he often begins a work with writing, with a title. ‘I am more inspired by writing than by painting’ he says. He has made works that are indicative of this impulse, the impulse to write, to reflect on writing, and, by extension, to create an archive of his own travels, memories, and experiences, but also of the memories and thoughts of others. This led to his creating an ongoing Le carnet de voyage and also a mammoth project called L’écriture infinie – envisioned as the ‘biggest archive of handwriting in the world’ in which people write as if what they are writing is the last thing they will write by hand in their lives. Bidjocka is inspired by African knowledge systems and draws on Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. A spectacular beaded curtain invokes the Seder question, ‘Why is this night different from all other nights?’ and suggests associations with sacred practices. A photograph of Venice adorned with beaded script inspired by Arabic texts asserts an Islamic presence largely occluded in the centres of Europe. In all of these movements, across religious and secular texts and practices, Bidjocka asserts the primacy of making meaning out of experience. Bidjocka has exhibited in the Johannesburg, Havana, Dakar, Taipei, and Venice biennales. He has also participated in landmark international exhibitions such as Zeitwenden at the Kunstmuseum in Bonn in 1999; Black President at the New Museum, New York in 2003; and Africa Remix (Düsseldorf, London, Paris, Tokyo, and Johannesburg, 2005– 2007). -

Full Concept and Programme (PDF)

unlearning the G i v e n Exercises in Demodernity and Decoloniality of Ideas and Knowledge A Performative, Discoursive and Corporeal Curatorial Framework for The Long Night of Ideas Ana Alenso: Reshaping Consuming, 2016 Curated by Elena Agudio and Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung SAVVY Contemporary The Laboratory of Form-Ideas Unlearning the Given is an event in the context of the forum Menschen bewegen (13.–15.4.2016) in cooperation with Auswärtiges Amt. For further information visit: www.menschenbewegen2016.de Programme 14.04.2016 15.04.2016 18.00–00.00 00.00–06.00 18.00 Introduction by the curators 00.00 DJ Cambel Nomi Afropop Unlearning the Given: Exercises 01.00 DJ İpek İpekçioğlu Orient-Jam in Demodernity and Decoloniality 02.00 DJ Lateef Soukous-Kuduru of Ideas and Knowledge 03.00 DJ Grace Kelly Afrobrazil-Latin Beats 18.10 Elsa Westreicher 04.00 Brothers in Love Funk-Garage-Soul Unveiling S AV V Y Contemporary's 05.00 Blessed Love Sound new visual identity Reggae-Dancehall 18.15 Natasha Ginwala Four Epigrams on Unlearning 18.35 Margarita Tsomou Greece between West and the Rest Durational 18.55 Mriganka Madhukaillya 18.00–00.00 Ana Alenso (desire machine collective) Reshaping Consuming Notebook of Geograph(ies) 18.00–00.00 Marinella Senatore 19.20 Balz Isler Film Screening: Unlearning Performance: Twilight 18.00–06.00 Zorka Wollny 20.15 Angela Melitopoulos Listening Installation: n -1 Order, Composition for Factory 20.35 Bili Bidjocka 19.00–21.00 Lerato Shadi Performance: Reading Lesson Badimo 20.55 Gabriel Rossell-Santillan 21.00–23.00 Nathalie Mba Bikoro Performance: Charred Perspectives: A If You Fail To Cross The Rubicon Shadowplay with Five Voices 22.00–00.00 Nikhil Chopra 21.30 Ida Momennejad Monster: Memory Drawing Critical epistemic practice: delinking science from the west and ideology critique through science 21.45 Marina Naprushkina Neue Nachbarschaft 22.05 Hiwa K Screening: Few Notes from an Extellectual Break 22.40 Jan Nikolai Nelles and Nora Al-Badri #Nefertitihack. -

African Pavilion – 52 Venice Biennale International Contemporary Art

African Pavilion – 52nd Venice Biennale International Contemporary Art Exhibition 10th June – 21st November 2007, Artiglierie dell’Arsenale Check-List Luanda Pop Contents 1 Press release 2 Check-List A reflection on fifteen years of African contemporary art around the world 2 The shock of being seen by Simon Njami 5 3 African Collection of Contemporary Art by Sindika Dokolo 10 4 Artists list 15 5 Artwork list 20 6 African Pavilion events 23 7 African Pavilion team 24 8 Institutions that supported the creation of the First African Pavilion in the 52nd Venice Biennale 25 Information Elise Atangana or Francisca Bagulho - [email protected] T : + 39 346 086 10 17 African Pavilion – 52nd Venice Biennale International Contemporary Art Exhibition 10th June – 21st November 2007, Artiglierie dell’Arsenale Check-List Luanda Pop For the first time in its official programme, the 52nd Venice Biennale International Contemporary Art Exhibition from 10 June to 21 November 2007 is presenting an African Pavilion. Check List Luanda Pop consecrates 30 artists from the the Sindika Dokolo Collection, the first African private collection of contemporary art located in Luanda, Angola. Alpha Oumar Konaré, President of the African Union Commission, is a member of the exhibition’s honorary committee. Simon Njami, the curator of Africa Remix and Fernando Alvim, Director of the Luanda Triennial have conceived this project as a manifesto for expression far from established trends or conventions. Check List is a space for thought, confrontation, and proposal. Press conference : 8th of June at 11:30 Hotel Monaco & Grand Canal, San Marco 2 Check List A reflection on fifteen years of African contemporary art around the world. -

Alexandre Arrechea

ALEXANDRE ARRECHEA Born in Trinidad, Cuba in 1970. Lives and works between Cuba and Madrid. EDUCATION 1994 Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), Havana, Cuba SOLO SHOW 2010 Ideational Arquitecture, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, LA Elasticity, Magnanmetz Gallery, New York City, NY Galeria Casado Santapau, Madrid 2009 Todo, Algo, Nada, CAB, Burgos, Spain 2008 American University Museum at the Katzen, Washington D.C. USA 2007 Espacio Derrotado, Casado-Santa Pau Gallery, Madrid, Spain Sweet Fear, Alonso Art, Miami, Florida. U.S.A Contemporary Links, San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, U.S.A. 2006 Taipei Biennial, Taipei, China Perpetual Free Entrance, Patio Herreriano, Museo de Arte contemporaneo Español, Valladolid, Spain The Limit, Mary Goldman Gallery, LA,California, Usa 2005 Dust, Magnan Projects, New York, Usa Polvo, Miramar Trade Center, La Habana, Cuba Nada Art Fair, Mary Goldman Gallery. Pulse, Magnan Projects, Miami Nowhere, Alonso Fine Art, Miami, Usa Raúl Cordero, Felipe Dulzaides, Alexandre Arrechea en la Casa de las Américas, Casa de las Americas, La Habana,Cuba 2004 Dos nuevos espacios, Espacio Aglutinador, La Habana, Cuba Arte público, Mark Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles, Ca, Usa Sudor, Proyecto de arte público, Havana, Cuba 2003 Novos Desenhos, Galeria Fortes-Vilaça, São Paulo, Brazil 2002 Ciudad Transportable, Contemporary Art Museum of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 2001 Túneles Populares, Palacio de Abrahante, Salamanca, Spain Los Carpinteros, Galería Camargo-Vilaça, São Paulo, Brazil Ciudad Transportable, PS1 Contemporary Art -

Bibliothèque Le Cube.Xlsx

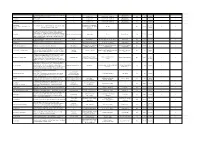

titre de l'exposition artistes curateurs auteurs lieu de l'exposition éditeurs nombre de pages année langue exposition d'artistes marocains nombre d'exemplaires Fouad Bellamine, Mahi Binebine, Mustapha Boujemaoui, James Brown, Villa Delaporte / / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français x 1 Safâa Erruas, Sâad Hassani, Aziz Lazrak art contemporains Villa Delaporte Après la pluie Pierre Gangloff / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 52p 2011 français 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Jacques Barry Angel For Ever / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français 1 art contemporains Yusur-Puentes Programmation culturelle de la Emilia Hernández Pezzi, Joaquín Ibáñez Montoya, Ainhoa Díez de Pablo, espagnol - Paysage et architecture au Maroc et en Présidence espagnole de l’Union Madrid 62p 2010 x 1 El Montacir Bensaïd, Iman Benkirane. français Espagne européenne Chourouk Hriech, Fouad Bellamine, Azzedine Baddou, Hassan Darsi, Ymane Fakhir, Faisal Samra, Fatiha Zemmouri, Mohamed Arejdal, Mohamed El Baz, Philippe Délis, Saad Tazi, Younes Baba Ali, Amande In, Between Walls Abdelmalek Alaoui, Yasmina Naji Yasmina Naji Rabat Integral Editions 44p 2012 français x 1 Anna Raimondo, Mohammed Fettaka, Ymane Fakhir, Mustapha Akrim, Hassan Ajjaj, Hassan Slaoui, Mohamed Laouli, Mounat Charrat, Tarik Oualalou, Fadila El Gadi Mohamed Abdel Benyaich, Hassan Darsi, Mounir Fatmi, Younes Regards Nomades Anne Dary Frédéric Bouglé Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole - France Ville de Dole 42p 1999 français x 1 Rahmoun, Batoul -

La Biennale De Dakar Comme Projet De Coopération Et De Développement

Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales en cotutelle avec Politecnico di Milano, Dipartimento di Architettura e Pianificazione Thèse de doctorat en Anthropologie sociale et ethnologie Governo e progettazione del territorio La Biennale de Dakar comme projet de coopération et de développement Candidat : Iolanda Pensa Directeurs de recherche Jean-Loup Amselle en cotutelle avec Rossella Salerno Jury Jean-Loup Amselle, Elio Grazioli, Rossella Salerno, Tobias Wendl Paris, 27 juin 2011 Iolanda Pensa, La Biennale de Dakar comme projet de coopération et de développement, 2011 [email protected] Pour texte et images de l'auteur Paternité-Partage des Conditions Initiales à l'Identique © Les auteurs et les artistes pour leurs images Font Gentium Basic 1.1 Victor Gaultney, 03/04/2008 © SIL Open Font License 1.1, 26/02/2006 Sommaire 5 Préface 7 Introduction 1. Objectifs et motivations scientifiques 8 – 2. Méthodologie et sources 10 – 3. Structure 12. 15 I. La Biennale de Venise 1. Le modèle historique de la Biennale de Venise 16 – 2. La première Biennale d'art de Dakar et le modèle de Venise 19 – 3. Ouverture et participation de l'Afrique à la Biennale de Venise 22 – 4. Le nouveau modèle de la Biennale de Dakar : Dak'Art devient une biennale d'art africain contemporain 31. 35 II. Les biennales africaines 1. Les caractéristiques des biennales 37 – 2. La Biennale du Caire 43 – 3. La Biennale de Cape Town 45 – 4. La Triennale de Luanda de 2007 58 – 5. La Triennale de Douala SUD- Salon Urbain de Douala 64. 75 III. Histoire de la Biennale de Dakar 1. -

A Summer of Art?

first word VENICE the 2017 Biennale’s curator Christine Macel Venice’s major art show had its first edition from France failed at this point in particular. in 1895 and already in its early years it opened Projects by only nine African artists were up European avant-garde art movements. shown in the main exhibition, themed “Viva African sculptures were shown in 1922, but Arte Viva,” at Arsenale and Giardini. after that year, African artists were not shown Most of the national pavilions showcase at the Venice Biennale until the 1990s. The only works by artists from their own coun- exhibitions “Authentic-Ex/Centric” curated tries. This can create an often unwelcome by Salah Hassan (2001),3 “Fault Lines” curated side effect, in that the artist thus becomes by Gilane Tawadros (2003),4 as well as the the “representative” of their country and is A Summer of Art? controversial so-called African Pavilion that seen first and foremost as the “South African“ by Nadine Siegert showcased the private collection of the Con- or the “Egyptian“ artist. Nevertheless, the golese businessmen Sindika Dokolo under 2017 was supposed to be one of these special the title “Check List Luanda Pop” (2007)5 years: a summer of the arts, also coined as were then dedicated to African and African “Art-Mageddon 2017” in some European Diaspora artists. In 2015, the Nigerian muse- 1 Peju Alatise Flying Girls (2013–2016) 1 art magazines. It was the year that aligned um director and curator Okwui Enwezor, Metal, fiberglass, plaster of Paris, resins, three major European art events—the Venice who had been in the same position at Docu- cellulose, black matte paint; installation size Biennale as well as Documenta in Kassel and menta in 2001, was the Head Curator of the 400 cm x 400 cm x 280 cm Skulptur Projekte Münster, the latter two in 56th Venice Biennale. -

Kendell Geers

Goodman Gallery Kendell Geers Biography South African-born, Belgian artist Kendell Geers changed his date of birth to May 1968 in order to give birth to himself as a work of art. Describing himself as an ‘AniMystikAKtivist’, Geers takes a syncretic approach to art that weaves together diverse Afro-European traditions, including animism, alchemy, mysticism, ritual and a socio- political activism laced with black humour, irony and cultural contradiction. Geers’s work has been shown in numerous international group exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale (2007) and Documenta (2002). Major solo shows include Heart of Darkness at Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town (1993), Third World Disorder at Goodman Gallery Cape Town (2010) and more recently Songs of Innocence and of Experience at Goodman Gallery Johannesburg (2012). His exhibition Irrespektiv travelled to Newcastle, Ghent, Salamanca and Lyon between 2007 and 2009. Geers was included on Art Unlimited at Art 42 Basel in 2011. Work by Geers was included on Manifesta 9 in Genk, Limburg, Belgium and a major survey show of his work was exhibited at Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany in 2013. Earlier this year Geers held a solo exhibition, The Second Coming (Do What Thou Wilt), at Rua Red in Dublin. Solo Exhibitions *2019*_THE SECOND COMING (Do What Thou Whilst), Rua Red, Dublin *2019*_#iPROtesttHERforIam, Galeria ADN, Barcelona 2018 VoetStoots, Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2018 Solo booth at AKAA, With Didier Claes gallery, Paris, France 2018 Hope is a Four Letters -

Fictions #3 Fictions #3

I b @ l k p b fid ‡ k ‡ o^ im o‡ p b k qb COMMUNIQUÉ EXPOSITION «FICTIONS #3 » D E P R E S S E À L'ABBAYE DE MAUBUISSON / SAINT-OUEN-L'AUMÔNE / VAL D’OISE / 7 AVRIL – 30 AOÛT 2010 FICTIONS #3 a k c o j d i B i l i B une exposition © e g n a r g de Bili Bidjocka a l r u o p à l’abbaye de Maubuisson n o i t a l u m i s , 2 2 1 # du 7 avril au 30 août 2010 e m g i n E Dans le cadre du projet départemental Visa pour l'Afrique, l'abbaye de Maubuisson a le plaisir de présenter une exposition monographique de l'artiste camerounais Bili Bidjocka. Le projet "FICTIONS #3" proposé sous le commissariat de Simon Njami est le troisième volet d’un projet d’expositions dont les deux premières étapes ("FICTIONS #1" et "FICTIONS #2") ont eu lieu au cours de l’été 2009 à la Goodman Gallery, Cape Town (Afrique du Sud), et en octobre-novembre 2009 à la Galerie Olivier Robert, Paris. Les œuvres de Bili Bidjocka - tableaux, sculptures, installations - fonctionnent comme autant d'énigmes à déchiffrer, selon les principes d'apparition-disparition et de visible-invisible propres à son travail. Dans la grange, lumière et obscurité révèlent l'ossature du bâtiment et font apparaître des silhouettes fantômatiques, évocatrices d’une présence féminine. Dans le décor gothique de la salle des religieuses, un rideau de perles géant s’inspire de la rencontre fictive entre Soundiata Keïta, empereur du Mali, et Saint Louis, roi de France et fils de Blanche de Castille (fondatrice de l'abbaye de Maubuisson au 13e siècle).