Recent Developments in Aviation Law Jonathan E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S:\Sean Cowley\Yahya V. Yemenia-Yemen Airways NWA's M

2:08-cv-14789-SFC-MKM Doc # 29 Filed 08/25/09 Pg 1 of 12 Pg ID 464 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION ABDEL MONEN YAHYA, Individually Case No. 08-14789 and as Personal Representative of the Estate of SAID MOSHIN YAHYA, DECEASED HONORABLE SEAN F. COX United States District Judge Plaintiffs, v. YEMENIA-YEMEN AIRWAYS, a Foreign Corporation for Profit; NORTHWEST AIRLINES, INC., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Delta Airlines, Inc., a Foreign Corporation for Profit; and GSA-ARABIAN HORIZONS TRAVEL AND TOURISM, a Foreign Corporation,, Defendants. _____________________________________/ AMENDED OPINION & ORDER GRANTING, WITH LEAVE TO AMEND, DEFENDANT NORTHWEST AIRLINES, INC.’S MOTION TO DISMISS [Doc. No. 6] Plaintiff Abdel Monen Yahya (“Plaintiff”), as personal representative of the Estate of Said Mohsin Yahya (“Yahya”) filed this cause of action on November 14, 2008 [Doc. No. 1], alleging that the defendant’s refusal to land an international flight during a health emergency caused Yahya’s death. The matter is before the Court on Defendant Northwest Airlines, Inc.’s (“Northwest”) Motion to Dismiss1 [Doc. No. 6], in which Northwest argues Plaintiff’s causes of action against Northwest are preempted by the Montreal Convention2. The parties have fully 1 The remaining defendants are not a party to Northwest’s Motion to Dismiss. 2 The Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air, May 28, 1999, S.Treaty Doc. No. 106-45, 2422 U.N.T.S. 350, commonly referred to as the “Montreal Convention.” 1 2:08-cv-14789-SFC-MKM Doc # 29 Filed 08/25/09 Pg 2 of 12 Pg ID 465 briefed the issues, and a hearing was held on May 21, 2009. -

Change 3, FAA Order 7340.2A Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.2A CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2A, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. July 29, 2010. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Changes, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. Y[fa\.Uj-Koef p^/2, Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: k/^///V/<+///0 Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 7/29/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 4/8/10 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 7/29/10 1−1−1 . 8/27/09 1−1−1 . 7/29/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 4/8/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 7/29/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−23 . -

United States District Court Eastern District of New York ______

Case 1:14-cv-05061-RER Document 32 Filed 02/25/16 Page 1 of 2 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK _____________________ No 14-cv-5061 (RER) _____________________ HUBERT BEARAM, Plaintiff, VERSUS CARRIBEAN AIRLINES LIMITED, Defendant. _________________________ Opinion & Order _________________________ RAMON E. REYES, JR., U.S.M.J.: 477 U.S. 242, 256, 106 S.Ct. 2505, 91 L.Ed.2d 202 (1986); Holcomb v. Iona Coll., This action was commenced by plaintiff 521 F.3d 130, 137 (2d Cir. 2008). A fact is Hubert Bearam in Kings County Civil Court “material” when it may affect the outcome to recover damages when the arrival of his of the suit. Anderson, 477 U.S. at 248. To flight from Georgetown, Guyana to New determine whether the moving party has York City was delayed three hours. satisfied this burden, the Court is required to Defendant Carribean Airlines Limited view the evidence and all factual inferences subsequently removed the action to this from that evidence in the light most Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1441(d) and favorable to the non-moving party. Doro v. the parties consented to my jurisdiction Sheet Metal Workers' Int'l Ass'n, 498 F.3d pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 636(c). Defendant 152, 155 (2d Cir. 2007); Woodman v. now seeks summary judgment in its favor. WWOR–TV, Inc., 411 F.3d 69, 75 (2d Cir. For the reasons which follow, defendant’s 2005). motion is granted. The Convention for the Unification of A “court shall grant summary judgment if Certain Rules for International Carriage by the movant shows that there is no genuine Air (“Montreal Convention”), an dispute as to any material fact and the international treaty to which the United movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of States is a party, establishes a uniform law.” Fed.R.Civ.P. -

Detailed Breakdown of Disability-Related Complaint Data: All Carriers

Detailed Breakdown of Disability-Related Complaint Data: All Carriers Total number of complaints submitted: 11,518 Carrier Name Number of Complaints AER LINGUS LIMITED 0 AERO CALIFORNIA 1 AERODYNAMICS, INC. 0 AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 0 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 0 AEROMEXICO 1 AEROPOSTAL ALAS DE VENEZUEL 3 AEROSVIT UKRANIAN AIRLINES 0 AIR ATLANTA EUROPE 16 AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC 0 AIR CANADA 248 AIR CANADA JAZZ 10 AIR CHINA 1 AIR COMET S.A. 0 AIR EUROPA LINEAS AEREAS 0 AIR FRANCE 30 AIR JAMAICA LIMITED 1 AIR JAPAN, CO 0 AIR LUXOR 0 AIR NEW ZEALAND 3 AIR PACIFIC, LTD. 0 AIR TAHITI NUI 1 AIR TRANSAT 17 AIR WISCONSIN 132 AIR-INDIA 4 AIRTRAN 87 ALASKA AIRLINES 215 ALITALIA-LINEE AEREE ITALIA 10 ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS CO. 0 ALLEGIANT 5 ALOHA AIRLINES 7 AMERICA WEST 536 AMERICAN AIRLINES 2061 AMERICAN EAGLE AIRLINES 171 ASIANA AIRLINES, INC. 3 ATA 94 ATLANTIC SOUTHEAST AIRLINES 191 AUSTRIAN AIRLINES 27 AVIACSA AIRLINES 3 AVIATION CONCEPTS 0 BAHAMASAIR HOLDING LIMITED 5 BOSTON-MAINE AIRWAYS 8 BRITANNIA AIRWAYS LTD. 147 BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC 165 BRITISH MIDLAND AIRWAYS LTD 16 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS 1 CASINO EXPRESS 1 CATHAY PACIFIC AIRWAYS, LTD 8 CHAMPION AIR 7 CHAUTAUQUA AIRLINES, INC 67 CHINA AIRLINES, LTD 3 CHINA EASTERN AIRLINES 0 COMAIR 301 COMPANIA MEXICANA DE AVIACI 1 COMPANIA PANAMENA (COPA) 3 CONDOR FLUGDIENST 0 CONTINENTAL 398 CONTINENTAL MICRONESIA 3 CZECH AIRLINES 2 DELTA AIR LINES 1326 EGYPTAIR 0 EL AL ISRAEL AIRLINES LTD. 66 EMIRATES AIRLINE 4 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 0 EUROATLANTIC AIRWAYS TRANSPORTES AE 0 EVA AIRWAYS CORPORATION 2 EXECUTIVE AIRLINES 11 FALCON AIR EXPRESS, INC. -

Center for Mobilities Research and Policy

Center for Mobilities Research and Policy Drexel E-Repository and Archive (iDEA) http://idea.library.drexel.edu/ Drexel University Libraries www.library.drexel.edu The following item is made available as a courtesy to scholars by the author(s) and Drexel University Library and may contain materials and content, including computer code and tags, artwork, text, graphics, images, and illustrations (Material) which may be protected by copyright law. Unless otherwise noted, the Material is made available for nonprofit and educational purposes, such as research, teaching and private study. For these limited purposes, you may reproduce (print, download or make copies) the Material without prior permission. All copies must include any copyright notice originally included with the Material. You must seek permission from the authors or copyright owners for all uses that are not allowed by fair use and other provisions of the U.S. Copyright Law. The responsibility for making an independent legal assessment and securing any necessary permission rests with persons desiring to reproduce or use the Material. Please direct questions to [email protected] sjtg_365 189..203 doi:10.1111/j.1467-9493.2009.00365.x The new Caribbean complexity: Mobility systems, tourism and spatial rescaling Mimi Sheller Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, USA Correspondence: Mimi Seller (email: [email protected]) The Caribbean region is being respatialized, rescaled and reterritorialized in the face of contempo- rary processes of neoliberal development, shifting mobilities and spatial restructuring. Drawing on the field of mobilities research, this paper argues that new transregional approaches to spatial dynamics are needed to describe the complex, polymorphic, and multiscalar geographies in the neoliberalizing Caribbean. -

Harvard Business School Tourism in Trinidad and Tobago

Harvard Business School Microeconomics of Competitiveness Tourism in Trinidad and Tobago Basilia Yao, Jan Krutzinna, Jennifer Chen, Kwabena Osei-Boateng, Tanveer Abbas May 5, 2006 Disclosure Note: Kwabena and Jan traveled to Trinidad for leisure/tourism during the project period. Introduction This paper analyzes the economy of Trinidad and Tobago and provides a strategic plan for developing the tourism cluster. Using the diamond model for competitiveness developed by Professor Michael Porter, we examine the strengths and weaknesses of the national economy, identify opportunities for improving the tourism cluster, and provide a set of policy recommendations to capture these opportunities. Macro-economic overview of Trinidad and Tobago Trinidad and Tobago (“T&T”) is a small energy-rich Caribbean economy. It has a population of 1,065,842 and a land area of 5,128 sq km (smaller than Delaware). The country came under British control in the 19th century and gained its independence in 1962. The ethnic mix of the country is approximately 40% Indian, 37.5% African, and about 21% mixed. The judicial system is based on English common law and the country has a bicameral Parliament which consists of the Senate and Tourism in Trinidad and Tobago Page 1 of 31 the House of Representatives.1 The Energy Curse The country is one of the most prosperous in the Caribbean because of its energy reserves. It has the world’s 43rd largest proven oil reserves and the world’s 33rd largest proven natural gas reserves.2 The oil and gas sector currently accounts for about 40 percent of GDP and 80 percent of exports. -

The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago: Application No

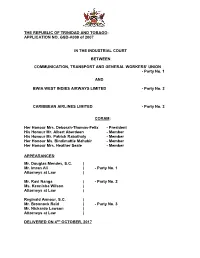

THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO: APPLICATION NO. GSD-A009 of 2007 IN THE INDUSTRIAL COURT BETWEEN COMMUNICATION, TRANSPORT AND GENERAL WORKERS’ UNION - Party No. 1 AND BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED - Party No. 2 CARIBBEAN AIRLINES LIMITED - Party No. 3 CORAM: Her Honour Mrs. Deborah-Thomas-Felix - President His Honour Mr. Albert Aberdeen - Member His Honour Mr. Patrick Rabathaly - Member Her Honour Ms. Bindimattie Mahabir - Member Her Honour Mrs. Heather Seale - Member APPEARANCES: Mr. Douglas Mendes, S.C. ) Mr. Imran Ali ) - Party No. 1 Attorneys at Law ) Mr. Ravi Nanga ) - Party No. 2 Ms. Kennisha Wilson ) Attorneys at Law ) Reginald Armour, S.C. ) Mr. Bronnock Reid ) - Party No. 3 Mr. Nickardo Lawson ) Attorneys at Law ) DELIVERED ON 4TH OCTOBER, 2017 JUDGMENT This application has some history before the Industrial Court. There have been a number of interlocutory hearings and a ruling on a preliminary point by the Court of Appeal before the commencement of the actual hearing. Final submissions were filed on 31st May, 2017 and we can now give a determination on the issues at hand. 1. The Communication, Transport and General Workers’ Union (the “Union”) is a registered Trade Union and the Recognised Majority Union for some of the bargaining units of BWIA West Indies Airways Limited (“BWIA”). BWIA is a Company registered under the Companies Act, Chapter 81:01, and was the national airline and “flag carrier” of Trinidad and Tobago until 31st December, 2006. Its principal shareholder was the Government of Trinidad and Tobago. Caribbean Airlines Limited (“CAL”) is a Company also registered under the Companies Act, Chapter 81:01. -

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

BWIA West Indies Airways Limited

January 6, 2004 Trading Sector Trading Sector Company Profiles BWIA West Indies Airways Limited Recent Price $ 2 .25 EPS(est.2003) $ - $8.00 52 Wk Range $ 1.60 - 2.25 Div.(est.2003) $ - $7.50 Shares O/s 47,533,856 Yld(est.2003) 0.00% $7.00 $6.50 Float 39,876,152 P/E (est.2003) N/A $6.00 Market Cap. $ 106,951,176 Fiscal Yr End December $5.50 $5.00 ACTUAL 2002 2001 2000 $4.50 $4.00 $3.50 P/E Ratio N/A N/A N/A $3.00 $2.50 EPS $ ( 4.65) $ (0.20) $ 0 .09 $2.00 Div. Payout Nil Nil Nil $1.50 $1.00 ROE% (Avg) N/A N/A 6.85% $0.50 $0.00 2 1 1 3 3 2 1 2 1 0 0 03 02 02 01 0 03 0 02 03 04 01 0 0 0 0 03 02 01 - - - - - - - - - - l l l t ROA% (Avg) N/A N/A 0.73% r-0 y- y- c c b- b- n- n- b- p- p- p- a e e u a e Ju Ju Ju Apr Apr Oc J J F F F M Se Nov Se Nov De Se De Ma B.V. / Share $ ( 2.67) $ 1 .88 $ 1 .96 Ma LT Debt $ 252, 943,000 $ 330, 862,000 $ 176 ,454,000 Pref. Equity $ 59, 500,000 $ 59,500,000 $ 5 9,500,000 Comm. Equity -$ 126,984,000 $ 89, 127,000 $ 9 3,140,000 The July to September quarter is the best period for BWIA with the usual two-way passenger traffic. -

Summary of Disability-Related Complaint Data All Carriers Total Number of Complaints Submitted: 13,584

Summary of Disability-Related Complaint Data All Carriers Total number of complaints submitted: 13,584 Carrier Name Number of Complaints AER LINGUS LIMITED 2 AERO CALIFORNIA 0 AERODYNAMICS, INC. 0 AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 0 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 0 AEROMEXICO 3 AEROPOSTAL ALAS DE VENEZUEL 0 AEROSERVICES CORPORATE 0 AEROSVIT UKRANIAN AIRLINES 0 AIR ATLANTA EUROPE 0 AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC 0 AIR CANADA 160 AIR CANADA JAZZ 13 AIR CHINA 0 AIR COMET S.A. 0 AIR EUROPA LINEAS AEREAS 0 AIR FRANCE 83 AIR JAMAICA LIMITED 7 AIR JAPAN, CO 0 AIR LUXOR 0 AIR NEW ZEALAND 0 AIR PACIFIC, LTD. 0 AIR TAHITI NUI 0 AIR TRANSAT 15 AIR WISCONSIN 168 AIR-INDIA 1 AIRTRAN 134 ALASKA AIRLINES 265 ALITALIA-LINEE AEREE ITALIA 6 ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS CO. 1 ALLEGIANT 31 ALOHA AIRLINES 10 AMERICA WEST 380 AMERICAN AIRLINES 2616 AMERICAN EAGLE AIRLINES 443 ASIANA AIRLINES, INC. 4 ATA 68 ATLANTIC SOUTHEAST AIRLINES 209 AUSTRIAN AIRLINES 4 AVIACSA AIRLINES 3 AVIANCA 2 AVIATION CONCEPTS 0 BAHAMASAIR HOLDING LIMITED 1 BELAIR AIRLINES 0 BOSTON-MAINE AIRWAYS 4 THOMSONFLY LTD. 124 BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC 144 BRITISH MIDLAND AIRWAYS LTD 15 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS 0 CASINO EXPRESS 1 CATHAY PACIFIC AIRWAYS, LTD 5 CHAMPION AIR 6 CHAUTAUQUA AIRLINES, INC 97 CHINA AIRLINES, LTD 2 CHINA EASTERN AIRLINES 0 COMAIR 238 COMPANIA MEXICANA DE AVIACI 7 COMPANIA PANAMENA (COPA) 10 CONDOR FLUGDIENST 0 CONTINENTAL 614 CONTINENTAL MICRONESIA 5 CZECH AIRLINES 48 DELTA AIR LINES 1669 EGYPTAIR 0 EL AL ISRAEL AIRLINES LTD. 93 EMIRATES AIRLINE 1 EOS AIRLINES 0 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 0 EUROATLANTIC AIRWAYS TRANSPORTES AE 0 EVA AIRWAYS CORPORATION 2 EXCEL AIRWAYS 0 EXECUTIVE AIRLINES 43 FALCON AIR EXPRESS 1 FINNAIR OY 0 FIRST CHOICE AIRWAYS 6 FRONTIER AIRLINES 69 GOJET AIRLINES, LLC 0 HAWAIIAN AIRLINES 115 HMY AIRWAYS, INC. -

Bwia West Indies Airways Limited

BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED REGISTERED OFFICE: Sunjet House 30 Edward Street Port of Spain Trinidad & Tobago TELEPHONE: (868) 627-2942 (868) 625-1845 WEBSITE: www.bwee.com E-MAIL: [email protected] ADMINISTRATION OFFICES: Administration Building Golden Grove Road Piarco Trinidad & Tobago TELEPHONE: (868) 669-3000 FAX: (868) 669-1680 BWIA 2004-11 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED REGISTRAR: BWIA West Indies Airways Limited Golden Grove Road Piarco Trinidad & Tobago DIRECTORS: Lawrence A. Duprey, CMT – Chairman Charles Anthony Jacelon, SC – Dep. Chairman Krishna Narinesingh, CMT Captain John O’Brien Rodney Sastri Prasad Michael Small Neil Parsanlal GENERAL MANAGER: Nelson Tom Yew SECRETARY: Nicole Richards BANKERS: RBTT Bank Limited Citibank N.A Royal Court 111 Wall Street, New York 19 – 21 Park Street New York, 10043 Port of Spain United States of America. Trinidad and Tobago BWIA 2004-11 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED ATTORNEYS-AT-LAW: Pollonais, Blanc, de la Bastide & Jacelon 17 - 19 Pembroke Street Port of Spain Trinidad &Tobago SUBSIDIARIES: West Indies Aircraft Limited (Cayman Islands) - 100.00% West Indies Aircraft Limited 2 (Cayman Islands) - 100.00% Allied Caterers Limited (Trinidad & Tobago) - 55.00% Tobago Express Limited (Trinidad & Tobago) – 49.00% ASSOCIATED COMPANY: LIAT (1974) Limited (Antigua) – 23.60% AUDITORS: PricewaterhouseCoopers 11-13 Victoria Avenue Port of Spain Trinidad & Tobago BWIA 2004-11 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED HISTORY AND BUSINESS: The Company traces its origins to British West Indian Airways, a privately owned airline which served the routes of Trinidad, Barbados and Tobago. The original airline was founded in 1940. By the 1950s, these routes had expanded to include services to Miami, Florida, USA, Venezuela, and Jamaica. -

Members by Region

FOUNdaTIONFOCUS Members by Region Canada/USA Airports Avaya Aviation DuPont Jeld-Wen Sanofi-Aventis Duncan Aviation Jeppesen Airlines Vancouver International Airport Authority Avjet Corp. EG&G Technical Services Jet Aviation ATA Airlines Westchester County Airport B&C Aviation EVASWorldwide Jetport Air Canada Manufacturers & Engine BP America Earth Star Johnson & Johnson Air Transport International Airbus Ball Corp. Eastman Chemical Co. Johnson Controls AirTran Airways Avionica Bank of America Eastman Kodak Co. K-Services Alaska Airlines Boeing Commercial Airplanes Bank of Stockton Eaton Corp KB Home Aloha Airlines Bombardier Aerospace Aircraft Services Barnes & Noble Bookstores Eclipse Aviation Corp. KaiserAir American Airlines Calspan Corp. Basin Electric Power Coop. Eli Lilly & Co. Kellogg Co. Astar Air Cargo Dassault Falcon Jet Battelle Memorial Institute EMC Corp. KeyCorp Aviation Co. Atlas Air GE Aviation Baxter Healthcare Corp. Emerson Electric Co. Koch Business Holdings Baron Aviation Services Gulfstream Aerospace Bechtel Corp. Entergy Services The Kroger Co. CargoJet Airways Honeywell BellSouth Corporate Aviation Execaire Level 3 Communications Champion Air Indal Technologies Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee ExxonMobil Corp. Liberty Global Continental Airlines Lockheed Martin Corporate Aircraft Bombardier Club Challenger FHC Flight Services Limited Brands Continental Micronesia Pratt & Whitney Bombardier FlexJet First Quality Enterprises Lucent Technologies Delta Air Lines Pratt & Whitney Canada Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. FL Aviation M&N Aviation Era Helicopters Raytheon Aircraft Co. Brunswick Corp. FlightWorks Magic Carpet Aviation Evergreen International Rockwell Automation Business & Commercial Aviation Florida Power & Light Co. Marathon Oil Co. FedEx Express Rolls-Royce North America C&S Wholesale Grocers Flowers Industries The Marmon Group Forward Air International Airlines Safe Flight Instrument Corp.