Review for Population Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

List of participants Conference of European Statisticians 69th Plenary Session, hybrid Wednesday, June 23 – Friday 25 June 2021 Registered participants Governments Albania Ms. Elsa DHULI Director General Institute of Statistics Ms. Vjollca SIMONI Head of International Cooperation and European Integration Sector Institute of Statistics Albania Argentina Sr. Joaquin MARCONI Advisor in International Relations, INDEC Mr. Nicolás PETRESKY International Relations Coordinator National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Elena HASAPOV ARAGONÉS National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Armenia Mr. Stepan MNATSAKANYAN President Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia Ms. Anahit SAFYAN Member of the State Council on Statistics Statistical Committee of RA Australia Mr. David GRUEN Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics 1 Ms. Teresa DICKINSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Ms. Helen WILSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria Mr. Tobias THOMAS Director General Statistics Austria Ms. Brigitte GRANDITS Head International Relation Statistics Austria Azerbaijan Mr. Farhad ALIYEV Deputy Head of Department State Statistical Committee Mr. Yusif YUSIFOV Deputy Chairman The State Statistical Committee Belarus Ms. Inna MEDVEDEVA Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Irina MAZAISKAYA Head of International Cooperation and Statistical Information Dissemination Department National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Elena KUKHAREVICH First Deputy Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Belgium Mr. Roeland BEERTEN Flanders Statistics Authority Mr. Olivier GODDEERIS Head of international Strategy and coordination Statistics Belgium 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina Ms. Vesna ĆUŽIĆ Director Agency for Statistics Brazil Mr. Eduardo RIOS NETO President Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE Sra. -

United Nations Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics

UNITED NATIONS United Nations Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics Implementation Guidelines United Nations Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics Implementation guidelines (Final draft, subject to editing) (January 2015) Table of contents Foreword 3 Introduction 4 PART I: Implementation guidelines for the Fundamental Principles 8 RELEVANCE, IMPARTIALITY AND EQUAL ACCESS 9 PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS, SCIENTIFIC PRINCIPLES, AND PROFESSIONAL ETHICS 22 ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY 31 PREVENTION OF MISUSE 38 SOURCES OF OFFICIAL STATISTICS 43 CONFIDENTIALITY 51 LEGISLATION 62 NATIONAL COORDINATION 68 USE OF INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS 80 INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION 91 ANNEX 98 Part II: Implementation guidelines on how to ensure independence 99 HOW TO ENSURE INDEPENDENCE 100 UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics – Implementation guidelines, 2015 2 Foreword The Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics (FPOS) are a pillar of the Global Statistical System. By enshrining our profound conviction and commitment that offi- cial statistics have to adhere to well-defined professional and scientific standards, they define us as a professional community, reaching across political, economic and cultural borders. They have stood the test of time and remain as relevant today as they were when they were first adopted over twenty years ago. In an appropriate recognition of their significance for all societies, who aspire to shape their own fates in an informed manner, the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics were adopted on 29 January 2014 at the highest political level as a General Assembly resolution (A/RES/68/261). This is, for us, a moment of great pride, but also of great responsibility and opportunity. In order for the Principles to be more than just a statement of noble intentions, we need to renew our efforts, individually and collectively, to make them the basis of our day-to-day statistical work. -

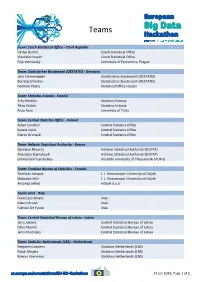

European Big Data Hackathon

Teams Team: Czech Statistical Office - Czech Republic Václav Bartoš Czech Statistical Office Vlastislav Novák Czech Statistical Office Filip Vencovský University of Economics, Prague Team: Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) - Germany Jana Emmenegger Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Bernhard Fischer Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Normen Peters Statistical Office Hessen Team: Statistics Estonia - Estonia Arko Kesküla Statistics Estonia Tõnu Raitviir Statistics Estonia Anto Aasa University of Tartu Team: Central Statistics Office - Ireland Aidan Condron Central Statistics Office Sanela Jojkic Central Statistics Office Marco Grimaldi Central Statistics Office Team: Hellenic Statistical Authority - Greece Georgios Ntouros Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Anastasia Stamatoudi Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Emmanouil Tsardoulias Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH) Team: Croatian Bureau of Statistics - Croatia Tomislav Jakopec J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Slobodan Jelić J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Antonija Jelinić mStart d.o.o Team: Istat - Italy Francesco Amato Istat Mauro Bruno Istat Fabrizio De Fausti Istat Team: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia - Latvia Janis Jukams Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Dāvis Kļaviņš Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Jānis Muižnieks Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Team: Statistics Netherlands (CBS) - Netherlands Benjamin Laevens Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Ralph Meijers Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Rowan Voermans Statistics Netherlands (CBS) 31 -

Annex 3: Sources, Methods and Technical Notes

Annex 3 EAG 2007 Education at a Glance OECD Indicators 2007 Annex 3: Sources 1 Annex 3 EAG 2007 SOURCES IN UOE DATA COLLECTION 2006 UNESCO/OECD/EUROSTAT (UOE) data collection on education statistics. National sources are: Australia: - Department of Education, Science and Training, Higher Education Group, Canberra; - Australian Bureau of Statistics (data on Finance; data on class size from a survey on Public and Private institutions from all states and territories). Austria: - Statistics Austria, Vienna; - Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Culture, Vienna (data on Graduates); (As from 03/2007: Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture; Federal Ministry for Science and Research) - The Austrian Federal Economic Chamber, Vienna (data on Graduates). Belgium: - Flemish Community: Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, Brussels; - French Community: Ministry of the French Community, Education, Research and Training Department, Brussels; - German-speaking Community: Ministry of the German-speaking Community, Eupen. Brazil: - Ministry of Education (MEC) - Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) Canada: - Statistics Canada, Ottawa. Chile: - Ministry of Education, Santiago. Czech Republic: - Institute for Information on Education, Prague; - Czech Statistical Office Denmark: - Ministry of Education, Budget Division, Copenhagen; - Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen. 2 Annex 3 EAG 2007 Estonia - Statistics office, Tallinn. Finland: - Statistics Finland, Helsinki; - National Board of Education, Helsinki (data on Finance). France: - Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research, Directorate of Evaluation and Planning, Paris. Germany: - Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden. Greece: - Ministry of National Education and Religious Affairs, Directorate of Investment Planning and Operational Research, Athens. Hungary: - Ministry of Education, Budapest; - Ministry of Finance, Budapest (data on Finance); Iceland: - Statistics Iceland, Reykjavik. -

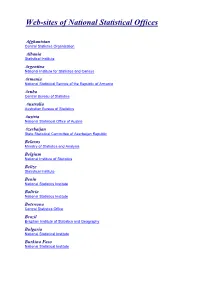

Web-Sites of National Statistical Offices

Web-sites of National Statistical Offices Afghanistan Central Statistics Organization Albania Statistical Institute Argentina National Institute for Statistics and Census Armenia National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia Aruba Central Bureau of Statistics Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria National Statistical Office of Austria Azerbaijan State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic Belarus Ministry of Statistics and Analysis Belgium National Institute of Statistics Belize Statistical Institute Benin National Statistics Institute Bolivia National Statistics Institute Botswana Central Statistics Office Brazil Brazilian Institute of Statistics and Geography Bulgaria National Statistical Institute Burkina Faso National Statistical Institute Cambodia National Institute of Statistics Cameroon National Institute of Statistics Canada Statistics Canada Cape Verde National Statistical Office Central African Republic General Directorate of Statistics and Economic and Social Studies Chile National Statistical Institute of Chile China National Bureau of Statistics Colombia National Administrative Department for Statistics Cook Islands Statistics Office Costa Rica National Statistical Institute Côte d'Ivoire National Statistical Institute Croatia Croatian Bureau of Statistics Cuba National statistical institute Cyprus Statistical Service of Cyprus Czech Republic Czech Statistical Office Denmark Statistics Denmark Dominican Republic National Statistical Office Ecuador National Institute for Statistics and Census Egypt -

Mission Report

TWINNING CONTRACT Institutional Capacity Building for the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS) and Developing the Legal Framework for Statistics in Egypt EG/07/AA/F106 MISSION REPORT on Workshop on improving quality of economic indicators Component No 7/5.1.11 Mission carried out by Jaroslav Sixta, Czech Statistical Office and Marek Rojicek, Czech Statistical Office Cairo, 25 th – 29 th October 2009 Central Agency for Public Statistics Denmark Mobilisation and Statistics PHARE 2005 Author’s name, address, e-mail: Jaroslav Sixta Czech Statistical Office Na padesatem 81 100 82 Prague 10 Czech Republic Tel. +420 27405 4253 [email protected] Marek Rojicek Czech Statistical Office Na padesatem 81 100 82 Prague 10 Czech Republic Tel. +420 27405 2486 [email protected] Table of contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. General comments............................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Assessment and results........................................................................................................................................ 5 3. Conclusions and recommendations..................................................................................................................... 7 Annex 1. Terms of Reference ................................................................................................................................ -

Sources and Data Description

ANNEX B ANNEX B Sources and data description User guide: List of variables Variables used Page Chapter(s) Area 147 2 Age-adjusted mortality rates based on mortality data 148 1 Death rates due to diseases of the respiratory system 148 1 Employment at place of work and gross value added by industry 149 2 Gini index of household disposable income 149 1 Gross domestic product (GDP) 150 2 Homicides 151 1 Hospital beds 152 4 Household disposable income 153 1 Households with broadband connection 154 4 Housing expenditures as a share of household disposable income 155 1 Individuals with unmet medical needs 155 1 Labour force, employment at place of residence by gender, unemployment, total and growth 156 1 and 2 Labour force by educational attainment 158 1 Life expectancy at birth, total and by gender 159 1 Life satisfaction 159 1 Local governments in metropolitan areas 160 2 Metropolitan population, total and by age 161 2 Motor vehicle theft 162 1 Municipal waste and recycled waste 163 4 Number of rooms per person 163 1 Part-time employment 164 4 Perception of corruption 164 1 PCT patent and co-patent applications, total and by sector 165 2 Physicians 165 4 PM2.5 particle concentration 166 1 Population, total, by age and gender 166 2 Population mobility among regions 167 4 R&D expenditure 169 2 R&D personnel 170 2 Social network support 170 1 Subnational government expenditure, revenue, investment and debt 171 3 Voter turnout 171 1 Young population neither in employment nor in education or training 172 4 Youth unemployment 173 4 The tables refer to the years and territorial levels used in this publication. -

10. References

10. References Previous 9. Glossary of terms and abbreviations Up Contents ABS, Strategy for End-to-End Management of ABS Metadata, (2003) AMRADS, EU project, Final Report of the Working Group on Metadata, (2003) Booleman, M, Statistics Netherlands, The Dutch Metadata Model, (2004) Cluster of Systems of Metadata for Official Statistics (COSMOS), http://www.epros.ed.ac.uk/cosmos/ Czech Statistical Office, Conception of the Statistical Metadata System in the Czech Statistical Office, (2004) Czech Statistical Office, Global Architecture of the Statistical Meta-information System in the Czech Statistical Office, (2005) Eurostat, Eurostat Metadata: Architecture and Strategy, (2003) SDMX, Metadata Common Vocabulary, (2009), http://www.sdmx.org SDMX, Content-Oriented Guidelines, (2009), http://www.sdmx.org Hustoft, A, Statistics Norway, Development of a Variables Documentation System in Statistics Norway, (2004) http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/00 /doc_200713_en/doc_200713_en.pdf Lindblom, H, Statistics Sweden, The Metadata System at Statistics Sweden in an International Perspective, (2004) Meliskova, J, AMRADS project, External Users of Metadata: a Challenge for National Statistical Offices, (2003) OECD, Data and Metadata Reporting and Presentation Handbook, (2007), http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/46/17/37671574.pdf OECD, Management of Statistical Metadata at the OECD, (2006), http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/26/33/33869551.pdf Sundgren, B, Statistics Sweden, Advice Concerning the Strategic Decisions that have to be made by a Statistical Office when -

Main Indicators of the Visegrád Group Countries

CHAPTER TITLE CHAPTER MAIN INDICATORS OF THE VISEGRÁD GROUP COUNTRIES MAIN INDICATORS OF THE VISEGRÁD GROUP COUNTRIES © Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2018 © Czech Statistical Office, 2018 © Statistics Poland, 2018 © Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, 2018 Prepared by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office in cooperation with statistical offices of Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia Primary source of data in the publication is the database of Eurostat. All other sources are indicated in footnotes at the place of occurrence. Information on methodology: methodological notes linked to datasets under http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database as well as on the sites of data sources indicated CSONTENT Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2018 3 CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 3 COMPREHENSIVE INFORMATION EDUCATION AND RESEARCH Figure 1: Capitals and largest cities ............................................................ 12 Figure 11: Population by educational Table 1: Geographical information ............................................................. 13 attainment level, 2016 ................................................................................ 22 Table 2: Weight of Visegrád Group Table 8: Number of students in tertiary countries in the European Union ........................................................... 14 education ........................................................................................................ 22 Figure 12: Proportion of students in tertiary education as % of the population aged 20–24 -

To Apply the PHI to the Metropolitan Areas It Was Deemed Important to Identify the Adequated Administrative Level to Provide Evidence on Urban Inequalities

Supplementary Material S1: Additional information on the Local Administrative Unit and delimitation of each metropolitan area. To apply the PHI to the metropolitan areas it was deemed important to identify the adequated administrative level to provide evidence on urban inequalities. For this study the definition of a municipality from the Encyclopædia Britannica was applied (http://www.britannica.com/topic/municipality): «A municipality is a political subdivision of a state within which a municipal corporation has been established to provide general local government for a specific population concentration in a defined area (…). The municipality is one of several basic types of local government, the others being counties, townships, school districts, and special districts».). However, European countries have a diversified system of local government in which several different categories exist. For instance, the term municipality may be applied in France to the commune, in Italy to comune and in Portugal to município. EUROSTAT has set up a hierarchical system of Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) and Local Administrative Units (LAUs). NUTS are organized into four levels. NUTS 0 correspond to the 28 EU countries. NUTS 1 are the major socio-economic regions within a given country. NUTS 2 are basic regions for the application of regional policies and NUTS 3 are small regions for specific diagnoses. Below, the Local Administrative Units are also organized into two hierarchical levels: The upper LAU level (LAU level 1) and the lower LAU level (LAU level 2). For most European countries, LAU-2 corresponds to municipalities, except for Bulgaria and Hungary (Settlements), Ireland (Districts), Lithuania (Elderships), Malta (Councils), Denmark (Municipalities), Greece (Municipalities), Portugal (Parishes), and the United Kingdom (Wards) [47] (Table S1). -

Participants List for Working Party on National Accounts (WPNA)

Participants List for Working Party on National Accounts (WPNA) Liste des Participants pour Groupe de travail sur la comptabilité nationale (WPNA) 2/11/2009 - 6/11/2009 Sessions Session Start End Working Party on National Nov 5 2009 9:30AM Nov 6 2009 1:00PM Accounts OECD Member States or Permanent Delegations Australia/Australie Mr. Michael DAVIES +61 2 6252 6035 Acting Division Head +61 2 6252 8045 Macroeconomics & Integration Division [email protected] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) ABS House, 45 Benjamin Way ACT 2616 Belconnen Australia Australia/Australie Ms. Amanda SENEVIRATNE +61 2 6252 5338 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) ABS House, 45 Benjamin Way [email protected] ACT 2616 Belconnen u Australia Austria/Autriche Mr. Michael ANDREASCH +43 1 40420 5420 Senior Expert +43 1 40420 5499 External Statistics & Financial Accounts Division [email protected] Oesterreichische Nationalbank Otto Wagner Platz 3 1090 Wien Austria Austria/Autriche Mr. Ferdinand KASSBERGER +43 1 711 28 7715 Senior Expert, National Accounts Section +43 1 711 62 52 Directorate for Macro-economic Statistics [email protected] Statistics Austria v.at Guglgasse 13 1110 Vienna Austria Belgium/Belgique Mr. Pierre CREVITS +32 2 221 30 29 Head of National & Regional Accounts and Short +32 2 221 32 30 Term Indicators [email protected] National Bank of Belgium Boulevard de Berlaimont 14 1000 Bruxelles Belgium Page 1/15 as of Friday, November 20, 2009 Belgium/Belgique M. Bertrand JADOUL +32 2 221 5269 Assistant Adviser +32 2 221 3230 National & Regional Accounts and Short term [email protected] Indicators Banque Nationale de Belgique Boulevard de Berlaymont 14 1000 Belgium Canada/Canada Mr. -

Sources and Data Description

ANNEX B ANNEX B Sources and data description User guide: List of variables Variables used Page Area 166 Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions 166 Concentration of PM10 particles 166 Concentration of NO2 167 Employment and gross value added by industry 167 Employment at place of work 168 Gross domestic product (GDP) 169 Infant mortality 170 Labour force, employment at place of residency, unemployment; total and by gender 171 Labour force by educational attainment 172 Land cover and changes 172 Life expectancy, total and by gender 173 Local governments in metropolitan areas 174 Long-term unemployment 175 Mortality rates due to transport accidents 175 Motor vehicle theft 176 Municipal waste and recycled waste 177 Net ecosystem productivity (NEP) 177 Number of cars 178 Number of murders 179 Number of hospital beds 180 Number of physicians 181 Part-time employment 182 PCT patent applications, total and by sector; PCT co-patent applications 182 Population; total, by age and gender 183 Population in functional urban areas 184 Population mobility among regions 185 Primary and disposable income of households 186 R&D expenditure 187 R&D personnel 188 Scientific publications and citations 188 Subnational government expenditure, revenue and debt 189 Young population neither in employment nor in education or training 189 Youth unemployment 190 The tables refer to the years and territorial levels used in this publication. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.