Writing 20 Offers Instruction in the Complexities of Producing Written Analysis and Argument Characteristic of Intellectual Wo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiffany B. Saul

Tiffany B. Saul Middle Tennessee State University Forensic Institute for Research and Education 1301 East Main Street Box 89 Wiser-Patten Science Hall 106H Murfreesboro, TN 37132 [email protected] Education 2013-2017 Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Anthropology, University of Tennessee 2010-2013 Master of Science (MS) in Biology, Middle Tennessee State University 1998-2002 Bachelor of Science (BS) in Anthropology, Middle Tennessee State University Academic Appointments 2017-present Research Assistant Professor, Middle Tennessee State University (Forensic Institute for Research and Education and Dept. of Anthropology) 2015-2017 Graduate Research Assistant, University of Tennessee (Dept. of Anthropology) 2014-2015 Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Tennessee (Anthropology & Biology) 2013 (Fall) Graduate Research Assistant, University of Tennessee (Dept. of Anthropology) 2012-2013 Graduate Research Assistant, Forensic Institute for Research and Education 2010-2012 NSF Graduate Fellow, Middle Tennessee State University Teaching Experience 2017 World Prehistory (ANTH 2210/ 1 section-MTSU), Instructor 2016 Basic Forensic Crime Scene Processing School (TBI), Presenter 2016 Forensic Skeletal Search and Recovery Course (MTSU), Instructor 2016 Biometrics Field Training (FBI Fly Team), Instructor 2015 Human Origins (ANTH 110/1 section-UTK), Instructor 2014-2015 Human Osteology Lab (ANTH 480/3 sections-UTK), Teaching Assistant 2014 General Biology for Non-majors Lab (BIOL 102/ 2 sections-UTK), Instructor 2013 Career and Technical Education (CTE) Workshop, Session Director 2012 Basic Forensic Crime Scene Processing School (TBI), Presenter 2012-2013 NSF TRIAD GK-12 Program, Program Master Fellow 2011-2012 Career and Technical Education (CTE) Workshop, Curriculum Developer 2011 Homicide Investigation Course (TBI), Instructor Assistant 2011-2014 CSI: MTSU Summer Camp, Curriculum Developer and Instructor 2010-2012 NSF TRIAD GK-12 Program, Visiting Scientist/Research Mentor 2010 CSI: MTSU Summer Camp, Assistant Instructor T. -

The Body Farm 1 the Body Farm Rachel Hilton Salt Lake Community College Mortuary Science Department

The Body Farm 1 The Body Farm Rachel Hilton Salt Lake Community College Mortuary Science Department The Body Farm 2 The Body Farm The Body Farm, a strange and eerie term you may have heard in a book or on a television show, meaning exactly what it sounds like: an outdoor research facility where bodies are strategically placed in the sun, in the shade, in ponds and in trunks and examined to see the effects of time and certain elements. Why do we have several body farms in the United States and what purpose do they serve? One day the students and staff of body farms across the U.S. hope to aide law enforcement in catching criminals by making an atlas of what happens to the human body after death. By developing this atlas equipped with pictures, copious amounts of time will be saved by law enforcement, time that would otherwise be wasted on trying to develop a time of death. The education a body farm can provide for aspiring forensic anthropology students is endless. Many teachers have tried to simulate crime scenes in classrooms, and while they do work and give students a broader spectrum of inquiries, to have an actual body to study over time is the ultimate gift. Body Farms in the U.S Dr. William M. Bass’ inspiration for starting the body farm stemmed from a possible murder case presented to him by local police where they asked him to approximate time of death of a body whose resting place was disturbed when a couple decided to remodel their home. -

How I Set up My Own Body Farm by Jennifer Dean

How I Set Up My Own Body Farm By Jennifer Dean To prepare for a new forensic science elective at Camas High School, and determined to make this new course an exciting application of biology and chemistry principles, I began by collecting forensic science resources, ordering books and enrolling in the local community college course on forensic science. I spent every extra hour soaking up as much as I could about this field during the “time off” teachers get in the summer. I was particularly fascinated by the fields of forensic entomology and anthropology. From books such as Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach and Dr. Bill Bass’s work around the creation of a human body farm at the University of Tennessee Forensic Anthropology Center, I decided to create something similar for our new high school forensic science program. As we met for dinner after a day of revitalizing workshops in Seattle at an NSTA conference, I shared my thoughts about the creation of an animal body farm with my talented and dedicated colleagues. These teachers have a passion for their students and their work. I felt free to share these ideas with them and know I’d be supported in making it a reality. As the Science Department, we formally agreed to dedicate ourselves to submitting grants to make it a reality. Back at work, I sent copies of the farm proposal to my immediate supervisors, and they responded with letters of support. The next step was getting the farm started—with or without grant money—because the first class of forensic science would be starting in the fall. -

A Taphonomic Examination of Inhumed and Entombed Remains in Parma Cemeteries, Italy

ISSN: 2692-5389 DOI: 10.33552/GJFSM.2019.01.000518 Global Journal of Forensic Science & Medicine Research Article Copyright © All rights are reserved by Paola A Magni A Taphonomic Examination of Inhumed and Entombed Remains in Parma Cemeteries, Italy Edda Guareschi, Ian R Dadour and Paola A Magni* Medical, Molecular & Forensic Sciences, Murdoch University, Australia *Corresponding author: Paola A Magni, Medical, Molecular & Forensic Sciences, Received Date: April 15, 2019 Murdoch University, 90 South Street, Murdoch, Western Australia. Published Date: May 23, 2019 Abstract People of different cultures bury their dead in different ways, based on religious beliefs, historical rituals, or public health requirements. In Italy, cremation is still a limited practice compared to entombment and inhumation. Accordingly with the law, a buried body can be moved to the cemetery ossuary only if skeletonized. Generally, complete skeletonization occurs within 40 years following burial, but sometimes the body may mummify, or it may turn into adipocere. Globally, today burial space is limited with cemeteries facing a growing need for both burials and entombments. The present study considered the thanatological, taphonomical, anthropological, microbiological and geochemical examination of 408 human bodies exhumed from grave pits and stone tombs located in two cemeteries in Parma, Italy. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors associated with the process of the decomposition of such bodies were documented in order to identify which factors promote or reduce the time needed for skeletonization. Overall, the aim of this study was to improve the management of the body turnover in cemeteries, providing recommendations for cemetery management and turnover planning, with the goal of avoiding extra costs that may be attributed to the family and the State. -

Human Taphonomy Facilities

FOREN SIC FRI ILITIES ONOMDYA FYA C HUMAN TAPH WITH HEATHER @STEMResponseWLV HUMAN TAPHONOMIC FACILITIES A human taphonomy facility ( HTF) or body farm, is a facility whereby human cadavers are observed for the purpose of research particularly in forensic science. A HTF is used to research various aspects of forensic science such as anthropology, entomology and decomposition. This involves the processes which occur after death, environmental conditions, location, burial and movement. Not only are these facilities used by science students and researchers to explore and gain further knowledge, they are used to educate and train law enforcement and simulate case studies. @STEMResponseWLV HUMAN TAPHONOMIC FACILITIES Secure Thanatology Forensic Research Research Site Outdoor Station University of Quebec, Canada Northern Michigan University, Forensic Investigation USA Research Station Colorado Mesa UniversIty, USA Amsterdam Research Initiative for Complex For Forensic Sub-surface Taphonomy and Anthropology Research Anthropology Southern Illinois University, USA Forensic Osteology Research Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Forensic Anthropology Station Research Facility Western Carolina University, USA Texas State University, USA Florida Forensic Institue for Applied Anthropological Research, Security and Tactical Research Center Training. Sam Houston State University, USA University of South Florida, USA Forensic Anthropology Center The University of Tennesse, USA Australian Facility for Taphonomic Research University -

Decomposition Patterns of Buried Remains at Different Intervals in the Central Highveld Region of South Africa

Decomposition patterns of buried remains at different intervals in the Central Highveld region of South Africa A Marais-Werner1,*, J Myburgh2, A Meyer2, WC Nienaber2 and M Steyn3 1School of Health Care Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa 2Forensic Anthropology Research Centre, Department of Anatomy, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa 3School of Anatomical Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa *Corresponding author: A Marais-Werner, School of Health Care Sciences, University of Pretoria, Private Bag x 323, Arcadia, 0007, South Africa. Email: [email protected] Abstract Burial of remains is an important factor when one attempts to establish the post-mortem interval as it reduces, and in extreme cases, excludes oviposition by Diptera species. This in turn leads to modification of the decomposition process. The aim of this study was to record decomposition patterns of buried remains using a pig model. The pattern of decomposition was evaluated at different intervals and recorded according to existing guidelines. In order to contribute to our knowledge on decomposition in different settings, a quantifiable approach was followed. Results indicated that early stages of decomposition occurred rapidly for buried remains within 7–33 days. Between 14 and 33 days, buried pigs displayed common features associated with the early to middle stages of decomposition, such as discoloration and bloating. From 33 to 90 days advanced decomposition manifested on the remains, and pigs then reached a stage of advanced decomposition where little change was observed in the next ±90–183 days after interment. Throughout this study, total body scores remained higher for surface remains. -

The Law and Ethics of Using the Dead in Research By

THE LAW AND ETHICS OF USING THE DEAD IN RESEARCH BY CATHERINE M. HAMMACK A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Bioethics December, 2014 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Christine N. Coughlin, JD, Advisor Nancy King, JD, Chair Tanya Marsh, JD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to everyone at the Center for Bioethics, Health and Society and the Master of Arts in Bioethics program at Wake Forest University. I would like to extend my warmest thanks to each of my bioethics professors— Christine Coughlin, Dr. Heather Gert, Mark Hall, Dr. Michael Hyde, Dr. Ana Iltis, and Nancy King—for constantly teaching, challenging, and encouraging me. A special thanks to Vicky Zickmund for her everlasting patience and kindness. I am forever grateful for the guidance, support, advice, and encouragement from Christine Coughlin, Nancy King, and Tanya Marsh, who are far more than my Examination Committee—they are extraordinary mentors and role models, both professionally and personally. I am a better scholar and person for having had the pleasure of learning from each of them. There are no words to express my gratitude for my friends and family. My parents, Jim and Phyllis Hammack, have showed their unwavering support in every way possible throughout my academic career. From proofreading my drafts at midnight to “wearing beige,” my parents have done and been everything I have needed. My partner, Michael Derek Jacobs, has supported and encouraged me throughout all this madness and loved me anyway; his patience and positivity inspire me to do and be better. -

William M. Bass Page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME

William M. Bass Page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: William Marvin Bass, III DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: August 30, 1928; Staunton, Virginia MARRIED: August 8, 1953. Mary Ann (Owen) Bass, Ph.D. 1971 Kansas State University, Food Science and Nutrition. DECEASED March 27, 1993 Three sons, March 1, 1956; November 2, 1962; July 14, 1964. Married May 21, 1994. Annette C. Blackbourne. DECEASED May 25, 1997. Married December 17, 1997. Carol H. Miles. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: B.A. 1951 (Psychology) University of Virginia M.S. 1956 (Anthropology) University of Kentucky Ph.D. 1961 (Anthropology) University of Pennsylvania Dissertation title: Variation in the physical types of the prehistoric Plains Indians. Written in connection with the Smithsonian Institution and published as Memoir I of the Plains Anthropologist. D.A.B.F.A. 1978 Diplomate American Board of Forensic Anthropology Psychological (and Anthropological) Research Assistant, (Army), Army Medical Research Laboratory, Fort Knox, Kentucky, 1951-53. Psychophysiologist, (Civilian), Army Medical Research Laboratory, search in applied physical anthropology (Human Engineering), 1953-54. Personnel Counselor, Counseling Office, University of Kentucky, September, 1954 - June, 1955. Administrative Assistant, Counseling Office, University of Kentucky, June, 1955 - November, 1955. Acting Director of Counseling Office (upon death of Dr. Lyle W. Croft, Director, and until a Ph.D. could be obtained to fill the position), November, 1955 - June, 1956. FORMAL TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Instructor in Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, September, 1956 - January, 1960. Teaching Physical Anthropology and Anatomy and research in growth and development of children. Instructor in Anthropology, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska, January, 1960 - August, 1960. -

Personal Identification: Theory and Applications the Case Study Approach

M01_STEA0735_02_SE_C01.QXD 9/19/08 12:59 PM Page 1 SECTION I Personal Identification: Theory and Applications The Case Study Approach n the summer of 1990, four male friends entered an abandoned farmhouse in Iowa, but Ionly three emerged alive. While one stood watch outside, two of the men shot their friend multiple times and threw his body into a well behind the farmhouse. It remained there until it was recovered nearly a decade later. Could the last moments of his life be interpreted from his mangled bones? In another part of the Midwest, an incomplete, disar- ticulated female skeleton was found scattered along a riverbank. Two women of the same age, height, and ancestry were missing from the area. How could experts determine whether the handful of bones belonged to one woman or the other? Could this also be a case of foul play? No matter in what morose scenario unknown human remains are recovered, every jurisdiction in the United States has statutes requiring a medicolegal investigation of the identity of the individual and the circumstances of his or her death. By virtue of their expertise in skeletal biology, forensic anthropologists may be called upon by law enforce- ment agencies, coroners, medical examiners, and forensic pathologists to assist in the recovery of human remains, conduct skeletal analyses for the purposes of identification, describe the nature and extent of skeletal trauma, and potentially provide expert testi- mony in a court of law. Forensic anthropological services are typically requested when human remains are decomposed, burnt, fragmentary, cremated, dismembered, fully skele- tonized, or otherwise unidentifiable by visual means. -

Testing Reliability of Animal Models in Research and Training Programs in Forensic Entomology, Part II, Final Report

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Testing Reliability of Animal Models in Research and Training Programs in Forensic Entomology, Part II, Final Report Author(s): Kenneth G. Schoenly Ph.D. ; Robert D. Hall Ph.D. Document No.: 192281 Date Received: January 31, 2002 Award Number: 97-IJ-CX-0046 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Testing Reliability of Animal Models in Research and Training Programs in Forensic Entomology, Part 11. ea2 I NIJ Grant No. 97-IJ-CX-0046 Final Report on Findings Project Director: N. H. Haskell, Ph.D. with Kenneth G. Schoenly, Ph.D. Robert D. Hall, Ph.D. In Collaboration with the: University of Missouri University of Indianapolis University of Tennessee California State University, Stanislaus Duration of Proposed Project: 2 years Proposed Starting Date: October 1,1997 Termination Date: September 30,2001 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

The Body Farm”

Mini Review J Forensic Sci & Criminal Inves Volume-5 Issue 2 - September 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Kayleigh Hart DOI: 10.19080/JFSCI.2017.05.555662 “Human Taphonomy Facility” Aka “The Body Farm” Kayleigh Hart*1, Daryl Ainsworth2 and Anna Williams3 1Forensic Science and Profiling Reeds Certified Crime Scene Investigation, UK 2Research Assistant at University of Glasgow, UK 3Forensic Anthropology, UK Submission: September 22, 2017; Published: September 25, 2017 *Corresponding author: Kayleigh Hart, Forensic Science and Profiling Reeds Certified Crime Scene Investigation, UK, Email: Mini Review Would you donate your body to forensic science? her book entitled ‘The Body Farm’, the fifth book in the Dr. Kay Scarpetta series. The story revolves around an FBI agent In 1971 forensic pathologist Ben Caleb Sturghill [1] along investigating the murder of an 11-year-old girl who turns to a with another pathologist thought up the idea of the “body farm”, “clandestine research facility in Tennessee known as The Body scientifically referred to as a “Human Taphonomy Facility” Farm” to find answers. The story isn’t based on any particular or “Outdoor Anthropology Research Facility”. This idea came real-life case, but the inspiration for a facility in the story clearly about due to how little is understood about what happens to comesOne may from wonder the ARF. where the body farm acquires these our bodies after we die. Although the idea was there it remained bodies? just that until one year on in 1972 Dr. William Bass [2] turned the idea into reality thus opening the first body farm on a 2.5 acre wooded plot surrounded by razor wire fencing in Knoxville, Well, the University of Tennessee in Knoxville have an Tennesse. -

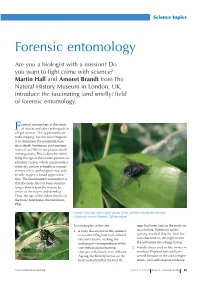

Forensic Entomology

SIS_2_38-61_RZ 08.07.2006 13:18 Uhr Seite 49 Science topics Forensic entomology Are you a biologist with a mission? Do you want to fight crime with science? Martin Hall and Amoret Brandt from The Natural History Museum in London, UK, introduce the fascinating (and smelly) field of forensic entomology. orensic entomology is the study of insects and other arthropods in Fa legal context. The applications are wide-ranging, but the most frequent is to determine the minimum time since death (minimum post-mortem interval, or PMI) in suspicious death investigations. This is done by identi- fying the age of the insects present on a human corpse, which can provide a relatively precise estimate in circum- stances where pathologists may only be able to give a broad approxima- tion. The fundamental assumption is that the body has not been dead for longer than it took the insects to arrive at the corpse and develop. Thus, the age of the oldest insects on the body determines the minimum PMI. Female (left) and male (right) adults of the common bluebottle blowfly, Calliphora vicina (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Two examples of this are: eggs had been laid on the body six 1. A body discovered in the summer days before. Witnesses subse- in southern England had suffered quently testified that the fatal fire extensive burns, making the was observed on the night before pathologist’s interpretation of the the estimated day of egg-laying. conventional post-mortem 2. A body discovered in late winter in changes in the body very difficult. northern England was well pre- Ageing the blowfly larvae on the served because of the cold temper- body indicated that the first fly atures, and pathological evidence www.scienceinschool.org Science in School Issue 2 : Summer 2006 49 SIS_2_38-61_RZ 08.07.2006 13:18 Uhr Seite 50 Adult blowflies are well adapted to If the ambient temperatures during sensing and locating the sources of the period of development are odours of decay, so cadavers are known, then, in theory, the minimum quickly found.