This Transcript Was Exported on Feb 12, 2021 - View Latest Version Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Water Presentation (SWGS)

Water for Life and Peace Smart Water for Green Schools in Ukraine Mission: providing sustainable access to safe drinking water and sanitation in Zhytomyr region General Information about Ukraine Location: Central Eastern Europe Capital: Kyiv Area: 603,000 km2 Population: 46 million people Ukraine consists of 24 oblasts and 1 autonomous republic of Crimea Neighbors: Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Moldova, Russian Federation and Belarus Black and Azov Sea wash Ukraine at the South Major Ukrainian rivers: Dnieper (total length of 2285 km), Dniester (1352 km), Southern Bug (806 km), Desna (1187 km), Seversky Donets (1053 km). Ukraine has a large amount of transboundary river basins with the neighboring countries: the Republic of Belarus, the Russian Federation, the Republic of Moldova, Romania, Hungary, the Slovak Republic, Poland. Ukraine is a country with an insufficient water supply - about 1.6 km³ of waters per inhabitant per year. Water Situation in Ukraine 69 percent of the drinking water delivered to homes does not meet sanitary standards in Ukraine. Every year the quality deteriorates, and one of the reasons for this is a catastrophic state of public water supply system. Some 18 thousand cities and villages around Ukraine have no access to safe water. Inhabitants of more then 1’150 settlements have to use imported and/or bottled water and public wells for their daily needs. General Information about Zhytomyr Region The Zhytomyr region is located in the North Western part of Ukraine. It consists of 23 districts including Ovruch and has a population of 1,271,000 people. Nearly half of the population resides in rural areas. -

From “A Theology of Genocide” to a “Theology of Reconciliation”? on the Role of Christian Churches in the Nexus of Religion and Genocide in Rwanda

religions Article From “a Theology of Genocide” to a “Theology of Reconciliation”? On the Role of Christian Churches in the Nexus of Religion and Genocide in Rwanda Christine Schliesser 1,2 1 Institute for Social Ethics, Zurich University, Zollikerstr. 117, 8008 Zurich, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 Studies in Historical Trauma and Transformation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch Central, Stellenbosch 7599, South Africa Received: 13 December 2017; Accepted: 18 January 2018; Published: 23 January 2018 Abstract: This paper explores the role of a specific religious actor, namely Christian churches, in the nexus of religion and genocide in Rwanda. Four factors are identified that point to the churches’ complicity in creating and sustaining the conditions in which the 1994 genocide could occur, leaving up to one million people dead. These factors include the close relationship between church and state, the churches’ endorsement of ethnic policies, power struggles within the churches, and a problematic theology emphasizing obedience instead of responsibility. Nevertheless, the portrayal of all Christian churches as collaborators of the genocide appears too simplistic and one-sided. Various church-led initiatives for peace and reconciliation prior to the genocide indicate a more complex picture of church involvement. Turning away from a “Theology of Genocide” that endorsed ethnic violence, numerous Christian churches in Rwanda now propagate a “Theology of Reconciliation.” A modest empirical case study of the Presbyterian Church (EPR) reveals how their “Theology of Reconciliation” embraces the four dimensions of theology, institutions, relationships, and remembrance. Based on their own confession of guilt in the Detmold Confession of 1996, the EPR’s engagement for reconciliation demonstrates religion’s constructive contribution in Rwanda’s on-going quest for sustainable peace and development. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Genocide, Ethnocide, Ecocide, with Special Reference to Indigenous Peoples: a Bibliography

Genocide, Ethnocide, Ecocide, with Special Reference to Indigenous Peoples: A Bibliography Robert K. Hitchcock Department of Anthropology and Geography University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68588-0368 [email protected] Adalian, Rouben (1991) The Armenian Genocide: Context and Legacy. Social Education 55(2):99-104. Adalian, Rouben (1997) The Armenian Genocide. In Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views, Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons and Israel W. Charny eds. Pp. 41-77. New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc. Adams, David Wallace (1995) Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875-1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. Africa Watch (1989) Zimbabwe, A Break with the Past? Human Rights and Political Unity. New York and Washington, D.C.: Africa Watch Committee. Africa Watch (1990) Somalia: A Government at War With Its Own People. Testimonies about the Killings and the Conflict in the North. New York, New York: Human Rights Watch. African Rights (1995a) Facing Genocide: The Nuba of Sudan. London: African Rights. African Rights (1995b) Rwanda: Death, Despair, and Defiance. London: African Rights. African Rights (1996) Rwanda: Killing the Evidence: Murders, Attacks, Arrests, and Intimidation of Survivors and Witnesses. London: African Rights. Albert, Bruce (1994) Gold Miners and Yanomami Indians in the Brazilian Amazon: The Hashimu Massacre. In Who Pays the Price? The Sociocultural Context of Environmental Crisis, Barbara Rose Johnston, ed. pp. 47-55. Washington D.C. and Covelo, California: Island Press. Allen, B. (1996) Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzogovina and Croatia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. American Anthropological Association (1991) Report of the Special Commission to Investigate the Situation of the Brazilian Yanomami, June, 1991. -

Format for Progress Report

Improving local capacity to promote and sustain entrepreneurship and SMEs development in Chernobyl affected territories by transferring best practices and experience of using smart instruments for boosting business Project Final Report 2015 _______________________________________________ Kyiv 2015 Improving local capacity to promote entrepreneurship and SMEs development in Chernobyl affected territories TABLE OF CONTENT Annotation .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose of the Report ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 4 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................ 6 2.1. Project genesis ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Project strategy ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

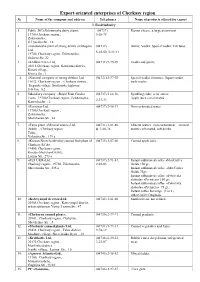

Export-Oriented Enterprises of Cherkasy Region № Name of the Company and Address Telephones Name of Products Offered for Export I

Export-oriented enterprises of Cherkasy region № Name of the company and address Telephones Name of products offered for export I. Food industry 1. Public JSC«Zolotonosha dairy plant», (04737) Rennet cheese, a large assortment 19700,Cherkasy region., 5-26-78 Zolotonosha , G.Lysenko Str., 18 2. «Zolotonosha plant of strong drinks «Zlatogor» (04737) Balms; Vodka; Special vodka; Tinctures. Ltd, 5-23-50, 5-39-41 19700, Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Sichova Str, 22 3. «Khlibna Niva» Ltd, (04732) 9-79-69 Vodka and spirits. 20813,Cherkasy region, Kamianka district, Kosari village, Kirova Str., 1 4. «National company of strong drinks» Ltd, (0472) 63-37-70 Special vodka, tinctures, liquers under 19632, Cherkasy region., Cherkasy district , trade marks. Stepanki village, Smilianske highway, 8-th km, б.2 5. Subsidiary company «Royal Fruit Garden (04737) 5-64-26, Sparkling cider, semi-sweet; East», 19700,Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Apple juice concentrated 2-27-73 Kanivska Str. , 2 6. «Econiya» Ltd, (04737) 2-16-37 Non-carbonated water. 19700,Cherkasy region , Zolotonosha , Shevchenko Str., 24 7. «Talne plant «Mineral waters»Ltd., (04731) 3-01-88, Mineral waters non-carbonated, mineral 20400, ., Cherkasy region ф. 3-08-36 waters carbonated, soft drinks Talne, Voksalna Str., 139 а 8. «Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy canned fruit plant of (04735) 2-07-60 Canned apple juice Cherkasy RCA», 19400, Cherkasy region., Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy, Lenina Str., 273 а 9. «FES UKR»Ltd, (04737) 2-91-84, Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Cherkasy region., 19700, Zolotonosha, 2-92-03 Gold» 150 gr; Shevchenka Str., 235 а Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Gold» 75gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 150 gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 75 gr.; Instant coffee beverage (3 in 1) «MacCoffee Original». -

Straining to Prevent the Rohingya Genocide: a Sociology of Law Perspective

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 12 Issue 3 Justice and the Prevention of Genocide Article 13 12-2018 Straining to Prevent the Rohingya Genocide: A Sociology of Law Perspective Katherine Southwick National University of Singapore Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Southwick, Katherine (2018) "Straining to Prevent the Rohingya Genocide: A Sociology of Law Perspective," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 12: Iss. 3: 119-142. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.12.3.1572 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss3/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Straining to Prevent the Rohingya Genocide: A Sociology of Law Perspective Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Centre for Asian Legal Studies at the National University of Singapore's Faculty of Law for its support of previous research into minority rights in Myanmar. I would also like to thank students and faculty at George Mason University's School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, who provided valuable feedback on an earlier version of this paper. This article is available in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss3/13 Straining to Prevent the Rohingya Genocide: A Sociology of Law Perspective Katherine Southwick National University of Singapore Based in Arlington, Virginia This paper analyzes the generally muted international response to the protracted plight of the Rohingya, a persecuted Muslim minority in Myanmar, from a sociology of law perspective. -

By Any Other Name: How, When, and Why the US Government Has Made

By Any Other Name How, When, and Why the US Government Has Made Genocide Determinations By Todd F. Buchwald Adam Keith CONTENTS List of Acronyms ................................................................................. ix Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Section 1 - Overview of US Practice and Process in Determining Whether Genocide Has Occurred ....................................................... 3 When Have Such Decisions Been Made? .................................. 3 The Nature of the Process ........................................................... 3 Cold War and Historical Cases .................................................... 5 Bosnia, Rwanda, and the 1990s ................................................... 7 Darfur and Thereafter .................................................................... 8 Section 2 - What Does the Word “Genocide” Actually Mean? ....... 10 Public Perceptions of the Word “Genocide” ........................... 10 A Legal Definition of the Word “Genocide” ............................. 10 Complications Presented by the Definition ...............................11 How Clear Must the Evidence Be in Order to Conclude that Genocide has Occurred? ................................................... 14 Section 3 - The Power and Importance of the Word “Genocide” .. 15 Genocide’s Unique Status .......................................................... 15 A Different Perspective .............................................................. -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

The Holocaust to Darfur: a Recipe for Genocide

Journal of Inquiry & Action in Education, 2(1), 2009 From the Holocaust to Darfur: A Recipe for Genocide Joseph D. Karb Springville (NY) Middle School and Andrew T. Beiter Springville (NY) Middle School All too often, social studies teachers present the cruelty of the Holocaust as an isolated event. These units focus on Hitler, gas chambers, and war crimes and end with a defiant and honorable “Never again!” While covering mass murder in this way is laudable, it ultimately might not go as far as it could. For as teaches if we really want to empower our students to prevent genocide, we must look beyond the facts alone to the larger lessons these horrific events can teach us. It is with this background in mind that we wrote this chapter; that in order to teach our students to be good, we have the obligation to help them develop their own understandings of where and why society has fallen off the tracks. The idea of a recipe provided us with a way to help students understand the early warning signs of mass murder such that they would be better equipped to prevent them in the future. Doing so would hopefully inspire them not to bystanders to any similar cruelty, both in the world and in their daily lives. After all, Rwandan President Paul Kagame notes, “people can be made to be bad, and they can also taught to be good.” My responsibility as a teacher is to try to help my students to be good people. And good people work to make the right choices and work against evil. -

A Brief History of the Ottoman Greek Genocide (1914-1923)

A Brief History of the Ottoman Greek Genocide (1914-1923) Asia Minor, also called Anatolia (from the Greek for “sunrise”), is a geographic Contemporary Eyewitness Accounts and historical term for the westernmost part of Asia. From the 9th century BC to the 15th century AD, Asia Minor played a major role in the development of From The Blight of Asia, by George Horton, U.S. Consul-General in the western civilization. Since 1923, Asia Minor has comprised the majority of the Near East, 1926: Republic of Turkey. “In January, 1916, the Greek deportations from the Black Sea began. These Greeks came through the city of Marsovan by thousands, walking for the Greek settlements in Asia Minor date as far back as the 11th century BC when most part the three days’ journey through the snow and mud and slush of Greeks emigrated from mainland Greece. They founded cities such as Miletus, the winter weather. Thousands fell by the wayside from exhaustion and Ephesus, Smyrna, Sinope, Trapezus, and Byzantium (later known as Constantinople, others came into the city of Marsovan in groups of fifty, one hundred and five the capital of the Byzantine Empire). These cities flourished culturally and hundred, always under escort of Turkish gendarmes. Next morning these poor economically. Miletus was the birthplace of pre-Socratic Western philosophy refugees were started on the road and destruction by this treatment was even and of the first great thinkers of antiquity, such as Thales, Anaximander, and more radical than a straight massacre such as the Armenians suffered before.” (p. 194) Anaximenes.