Windowscape: a Task Oriented Window Manager

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to the X Window System Introduction to X's Anatomy

An Introduction to the X Window System Robert Lupton This is a limited and partisan introduction to ‘The X Window System’, which is widely but improperly known as X-windows, specifically to version 11 (‘X11’). The intention of the X-project has been to provide ‘tools not rules’, which allows their basic system to appear in a very large number of confusing guises. This document assumes that you are using the configuration that I set up at Peyton Hall † There are helpful manual entries under X and Xserver, as well as for individual utilities such as xterm. You may need to add /usr/princeton/X11/man to your MANPATH to read the X manpages. This is the first draft of this document, so I’d be very grateful for any comments or criticisms. Introduction to X’s Anatomy X consists of three parts: The server The part that knows about the hardware and how to draw lines and write characters. The Clients Such things as terminal emulators, dvi previewers, and clocks and The Window Manager A programme which handles negotiations between the different clients as they fight for screen space, colours, and sunlight. Another fundamental X-concept is that of resources, which is how X describes any- thing that a client might want to specify; common examples would be fonts, colours (both foreground and background), and position on the screen. Keys X can, and usually does, use a number of special keys. You are familiar with the way that <shift>a and <ctrl>a are different from a; in X this sensitivity extends to things like mouse buttons that you might not normally think of as case-sensitive. -

A Successor to the X Window System

Y: A Successor to the X Window System Mark Thomas <[email protected]> Project Supervisor: D. R¨uckert <[email protected]> Second Marker: E. Lupu <[email protected]> June 18, 2003 ii Abstract UNIX desktop environments are a mess. The proliferation of incompatible and inconsistent user interface toolkits is now the primary factor in the failure of enterprises to adopt UNIX as a desktop solution. This report documents the creation of a comprehensive, elegant framework for a complete windowing system, including a standardised graphical user interface toolkit. ‘Y’ addresses many of the problems associated with current systems, whilst keeping and improving on their best features. An initial implementation, which supports simple applications like a terminal emulator, a clock and a calculator, is provided. iii iv Acknowledgements Thanks to Daniel R¨uckert for supervising the project and for his help and advice regarding it. Thanks to David McBride for his assistance with setting up my project machine and providing me with an ATI Radeon for it. Thanks to Philip Willoughby for his knowledge of the POSIX standard and help with the GNU Autotools and some of the more obscure libc functions. Thanks to Andrew Suffield for his help with the GNU Autotools and Arch. Thanks to Nick Maynard and Karl O’Keeffe for discussions on window system and GUI design. Thanks to Tim Southerwood for discussions about possible features of Y. Thanks to Duncan White for discussions about the virtues of X. All company and product names are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Security Assessment Login History by Computer

Security Assessment Login History by Computer CONFIDENTIALITY NOTE: The information contained in this report document is for the exclusive use of the client specified above and may contain Prepared for: confidential, privileged and non-disclosable information. If the recipient of this report is not the client or addressee, such recipient is strictly prohibited from Your Customer / Prospect reading, photocopying, distributing or otherwise using this report or its contents in any way. Prepared by: Your Company Name Scan Date: 10/25/2016 10/27/2016 Login History by Computer SECURITY ASSESSMENT Table of Contents 1 - Domain: Corp.myco.com 1.1 - b2b-GW 1.2 - betty-INSPIRON 1.3 - Boppenheimer-PC 1.4 - buildbox 1.5 - CERTEXAM 1.6 - CONFERENCE-ROOM 1.7 - darkhorse 1.8 - darren-PC 1.9 - DC03 1.10 - Ddouglas-WIN10 1.11 - DESKTOP-N6S4H9A 1.12 - DESKTOP-UAE29E6 1.13 - FILE2012-1 1.14 - gordon-LT2 1.15 - HPDT-8CC5260NXY 1.16 - HPLT-5CD4411D8Z 1.17 - HV00 1.18 - HV02 1.19 - HV04 1.20 - IRIDIUM 1.21 - ISTCORP-PC 1.22 - JIM-WIN8 1.23 - Lalexander-PC 1.24 - Mmichaels-HP 1.25 - Mwest-WIN864 1.26 - PANOPTICON 1.27 - PITWDS12 1.28 - PKWIN8-VM 1.29 - PS01 1.30 - Psolidad-PC 1.31 - Psolidad-WIN764 PROPRIETARY & CONFIDENTIAL PAGE 2 of 88 Login History by Computer SECURITY ASSESSMENT 1.32 - QB01 1.33 - REX 1.34 - ROWBOT 1.35 - SARLACC 1.36 - sourcesvr 1.37 - sourcesvrBUILD 1.38 - STORAGE01 1.39 - STORAGE12 1.40 - tarsis 1.41 - tywin-PC 1.42 - UTIL12 1.43 - VPNGW 1.44 - WAMPA 1.45 - WILLARD PROPRIETARY & CONFIDENTIAL PAGE 3 of 88 Login History by Computer SECURITY -

Xfce: the Missing Manual Documentation Release 0.1

Xfce: The Missing Manual Documentation Release 0.1 Joji Antony Jun 18, 2017 Contents 1 What is Xfce? 3 2 Why not use other lightweight environments ?5 3 What is your point? 7 4 Caveats of this document 9 5 How to install Xfce? 11 5.1 Linux................................................... 11 5.2 Installing Xfce on FreeBSD....................................... 21 5.3 Installing Xfce 4.12 on NetBSD..................................... 21 6 Components of Xfce 23 6.1 Xfce4 Settings Manager......................................... 23 6.2 Xfce Panel................................................ 23 6.3 Xfdesktop................................................ 24 6.4 Xfwm4.................................................. 24 6.5 Thunar.................................................. 24 7 Some goodies available with Xfce 25 7.1 Xfce Terminal Emulator......................................... 25 7.2 Mousepad................................................ 25 8 Using your keyboard shortcuts wisely 27 9 Scrolling 29 10 Indices and tables 31 i ii Xfce: The Missing Manual Documentation, Release 0.1 This is an unofficial user manual for Xfce, the lightweight desktop environment. This document is not meant to be comprehensive, and only attempts to cover the basics to get you up and running. Contents Contents 1 Xfce: The Missing Manual Documentation, Release 0.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 What is Xfce? Xfce is a lightweight desktop environment built for simplicity and efficiency. Xfce takes up far less space than other desktop environments such as KDE, GNOME, Unity etc and is very responsive. Xfce philosophy is to get out of your way and let you complete your work efficiently and easily. Xfce project has a high emphasis on stability meaning that core functionality does not change frequently causing you to re-learn your workflow. 3 Xfce: The Missing Manual Documentation, Release 0.1 4 Chapter 1. -

Arwin - a Desktop Augmented Reality Window Manager

ARWin - A Desktop Augmented Reality Window Manager Stephen DiVerdi, Daniel Nurmi, Tobias Hollerer¨ Department of Computer Science University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106 sdiverdi,nurmi,holl ¡ @cs.ucsb.edu ing concepts from Windows on the World [2], to integrate legacy 2D applications in the augmented environment, as well as the Tiles system [3], to provide a tangible inter- face to our augmented components. The result is a novel generic application architecture for general purpose com- puting. While AR lends itself very well to multi-user col- laborative work [1, 7], our scenario purposefully focuses on support of the single-user case, which is how most computer users spend the majority of their time. Our prototype environment, ARWIN, allows the user to work in a familiar fashion with traditional 2D GUI appli- cations, while introducing novel applications that are de- veloped specifically with the 3D augmented workspaces in mind. These applications can mimic or extend traditional desktop objects such as a clock or calendar, or can spa- tially visualize information, such as web or file hierarchies. Figure 1. A typical ARWin desktop, as seen through a video see- Thanks to the extra dimension in a volumetric workspace, through head-worn display (Sony LDI-A55 with Point Grey Fire- these applications can also interact in more intuitive ways, fly camera). Applications are (clockwise from right) weather re- port, tagged phone, business card, flowers, web browser, clock. based on physical relationships such as proximity. The re- sult of our work is the core ARWin architecture and the ap- plications we developed to showcase its capabilities. -

A Taxonomy of Window Manager User Interfaces

Window Interfaces A Taxonomy of Window Manager User Interfaces Brad A. Myers Carnegie Mellon University This article presents a taxonomy for the user-visible A window manager is a software package that helps parts of window managers. It is interesting that there the user monitor and control different contexts by are actually very few significant differences, and the separating them physically onto different parts of one or differences can be classified in a taxonomy with fairly more display screens. At its simplest, a window manager limited branching. This taxonomy should be useful in provides many separate terminals on the same screen, evaluating the similarities and differences of various each with its own connection to a time-sharing com- window managers, and it will also serve as a guide for puter. At its most advanced, a window manager supports the issues that need to be addressed by designers of many different activities, each of which uses many win- future window manager user interfaces. The advan- dows, and each window, in turn, can contain many tages and disadvantages of the various options are also different kinds of information including text, graphics, presented. Since many modern window managers allow the user interface to be customized to a large and even video. Window managers are sometimes imple- degree, it is important to study the choices available. mented as part of a computer’s operating system and sometimes as a server that can be used if desired. They September 1988 0272-1;1618810900-0065s0100 198R ltEE 65 Authorized licensed use limited to: Carnegie Mellon Libraries. -

Compiz Fusion

COMPIZ FUSION Salah Satu Window Manager di Linux By DEVINA DONA (devux) devin.53w-design.com [email protected] APA ITU COMPIZ FUSION ? Compiz Fusion adalah koleksi dari beberapa plugin-plugin dan sistem konfigurasi window manager Compiz untuk Sistem X Window, dimana penggunaan perangkat keras grafik untuk menampilkan efek – efek yang mengesankan, kecepatan yang mengagumkan dan tidak ada yang menyaingi. Compiz Fusion berasal dari hasil gabungan antara komunitas plugin Compiz yang lama kumpulan dari “Compiz Extras” dengan projek Beryl yang berdiri sendiri sebagai inti window manager. Rilis Compiz Fusion yang pertama yaitu Compiz Fusion 0.5.2 pada tanggal 13 Agustus 2007. Tujuan dari projek adalah hampir semua fitur-fitur Beryl dan Compiz plugin ada, dan terus melanjutkan plugin Compiz. Sampai saat ini, projek Beryl tidak dilanjutkan dan Compiz akan menambahkan sebagian dari perubahan inti yang dibuat oleh Beryl kepada inti Compiz. Nama telah diubah ke Compiz Fusion (Compiz Penyatuan) berasal dari CompComm. Compiz Fusion sebenarnya sangatlah sederhana untuk di install pada sistem operasi open source lainnya asalkan mendukung akan perangkat keras yang diperlukan. Pelopor pertama yang menggunakan Compiz Fusion adalah linux Mandriva 2008. Diikuti linux Ubuntu 7.10 dengan menggunakan Compiz Fusion sebagai standar window managernya dengan perangkat keras yang mendukung. Compiz Fusion itu sendiri seperti halnya Compiz, yaitu projek software open- source, yang artinya siapa saja dapat menggunakan dan mendistribusikan dengan bebas seperti halnya Linux. Ini sebagai catatan penting bahwa Compiz dan Compiz Fusion adalah tidak sama. Seperti yang disampaikan oleh komunitas Compiz Fusion bahwa ini pengembangan dari Compiz. Ini adalah kerjasama yang berbeda antara pengembang dari Compiz dengan pengembang Compiz Fusion, akan tetapi walaupun kenyataannya projek Compiz Fusion terdapat pengembang dari Compiz. -

GNOME 1.2 Desktop COMEBACK of THE

GNOME SOFTWARE GNOME 1.2 Desktop COMEBACK OF THE Ignored by many GNOME users and prematurely ANDREAS HUCHLER written-off by some distributions the GNOME desktop environment fights back with a new version. Here, we take a look at the most important components of Helix GNOME 1.2 to help you decide if an upgrade or new installation is worthwhile. About four years ago a group of Linux enthusiasts elements to be produced in a similar easy manner. on the Internet got together with the aim of devel- The differences were not resolved, so in the end oping a graphical user interface for Linux that would some of the developers decided to support the Qt- Helixcode stand comparison with Windows and Mac OS. based KDE project whilst the others started to cre- The American firm Helixcode, It’s true that at that time there were already sev- ate the gtk-based GNOME project. Inc. (http://www.helixcode.com) eral window managers – for example, fvwm2 and cofounded by GNOME evange- Afterstep – for the X interface; with CDE a desktop Co-operation list and author of Midnight environment was even available. However, these Commander Miguel de Icaza, solutions all had disadvantages – the window man- Over time, not least because of the subsequent has made it its goal to help agers had so session management nor support for open source licensing of Qt, the former rivalry GNOME break through as an drag and drop; CDE was commercial and obsolete – between the two projects gave way to a spirit of co- Internet desktop. In addition so there was a real need for a new graphical inter- operation. -

An Extensible Constraint-Enabled Window Manager

Scwm: An Extensible Constraint-Enabled Window Manager Greg J. Badros Jeffrey Nichols Alan Borning gjb,jwnichls,borning @cs.washington.edu f Dept. of Computer Scienceg and Engineering University of Washington, Box 352350 Seattle, WA 98195-2350, USA Abstract powerful, and satisfying. We desired a platform for researching advanced Using C to implement a highly-interactive applica- window layout paradigms including the use of con- tion also complicates extensibility and customiz- straints. Typical window management systems ability. To add a new feature, the user likely must are written entirely in C or C++, complicating write C code, recompile, relink, and restart the extensibility and programmability. Because no ex- application before changes are finally available for isting window manager was well-suited to our goal, testing and use. This development cycle is es- we developed the Scwm window manager. In pecially problematic for software such as a win- Scwm, only the core window-management primi- dow manager that generally is expected to run for tives are written in C while the rest of the pack- weeks at a time. Additionally, maintaining all the age is implemented in its Guile/Scheme exten- features that any user desires would result in ter- sion language. This architecture, first seen in rible code bloat. Emacs, enables programming substantial new fea- tures in Scheme and provides a solid infrastructure An increasingly popular solution to these prob- for constraint-based window layout research and lems is the use of a scripting language on top of other advanced capabilities such as voice recogni- a core system that defines new domain-specific tion. -

X Window System Architecture Overview HOWTO

X Window System Architecture Overview HOWTO Daniel Manrique [email protected] Revision History Revision 1.0.1 2001−05−22 Revised by: dm Some grammatical corrections, pointed out by Bill Staehle Revision 1.0 2001−05−20 Revised by: dm Initial LDP release. This document provides an overview of the X Window System's architecture, give a better understanding of its design, which components integrate with X and fit together to provide a working graphical environment and what choices are there regarding such components as window managers, toolkits and widget libraries, and desktop environments. X Window System Architecture Overview HOWTO Table of Contents 1. Preface..............................................................................................................................................................1 2. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 3. The X Window System Architecture: overview...........................................................................................3 4. Window Managers..........................................................................................................................................4 5. Client Applications..........................................................................................................................................5 6. Widget Libraries or toolkits...........................................................................................................................6 -

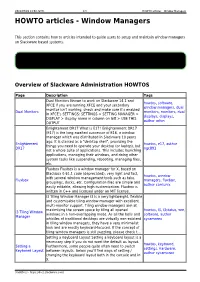

Window Managers HOWTO Articles - Window Managers

2021/07/26 13:08 (UTC) 1/3 HOWTO articles - Window Managers HOWTO articles - Window Managers This section contains how to articles intended to guide users to setup and maintain window managers on Slackware based systems. Inspired? Want to write a Window Manager HOWTO page yourself? Type a new page name (no spaces - use underscores instead) and start creating! You are not allowed to add pages Overview of Slackware Administration HOWTOS Page Description Tags Dual Monitors Known to work on Slackware 14.1 and howtos, software, XFCE If you are running XFCE and your secondary window managers, dual monitor isn't working, check and make sure it's enabled Dual Monitors monitors, monitors, dual in XFCE's SETTINGS: SETTINGS > SETTING MANAGER > displays, displays, DISPLAY > display name in column on left > USE THIS author arfon OUTPUT Enlightement DR17 What is E17? Enlightenment DR17 (E17) is the long awaited successor of E16, a window manager which was distributed in Slackware 10 years ago. It is classed as a “desktop shell”, providing the Enlightement howtos, e17, author things you need to operate your desktop (or laptop), but DR17 ngc891 not a whole suite of applications. This includes launching applications, managing their windows, and doing other system tasks like suspending, rebooting, managing files, etc. Fluxbox Fluxbox is a window manager for X, based on Blackbox 0.61.1 code (deprecated), very light and fast, howtos, window with several window management tools such as tabs, Fluxbox managers, fluxbox, groupings, docks, etc. Configuration files are simple and author carriunix easily editable, allowing high customization. Fluxbox is written in C++ and licensed under an MIT license. -

Tiling Window Managers

Overview Window Managers Tiling Algorithms Getting Started Demos Meta Tiling Window Managers Aline Abler April 4, 2016 Tiling Window Managers 1 Aline Abler Overview Window Managers Tiling Algorithms Getting Started Demos Meta Table of Contents What will we learn today? I What is a window manager? I What makes it tiling? I Why is tiling cool? I How does it work? I How do I put it on my system? I Which one should I use? Tiling Window Managers 2 Aline Abler Overview Window Managers Tiling Algorithms Getting Started Demos Meta Functionality of Window Managers Well, it manages windows You already have one Tiling Window Managers 3 Aline Abler Overview Window Managers Tiling Algorithms Getting Started Demos Meta Functionality of Window Managers Stacking Window Managers Each window is freely draggable and resizable Tiling Window Managers 4 Aline Abler Overview Window Managers Tiling Algorithms Getting Started Demos Meta Functionality of Window Managers When do we call it tiling? I Windows are arranged for you I They always take up the entire screen I You always see all of them How is that better? Tiling Window Managers 5 Aline Abler Overview Window Managers Tiling Algorithms Getting Started Demos Meta How to tile windows Tiling approaches List vs. Tree Tiling Window Managers 9 Aline Abler Overview Window Managers Tiling Algorithms Getting Started Demos Meta How to tile windows List based tiling I Windows are internally represented as ordered list I Arrangement is based on their positions in the list I Numerous ways to do this Tiling Window Managers