An Introduction to the X Window System Introduction to X's Anatomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release Notes for X11R6.8.2 the X.Orgfoundation the Xfree86 Project, Inc

Release Notes for X11R6.8.2 The X.OrgFoundation The XFree86 Project, Inc. 9February 2005 Abstract These release notes contains information about features and their status in the X.Org Foundation X11R6.8.2 release. It is based on the XFree86 4.4RC2 RELNOTES docu- ment published by The XFree86™ Project, Inc. Thereare significant updates and dif- ferences in the X.Orgrelease as noted below. 1. Introduction to the X11R6.8.2 Release The release numbering is based on the original MIT X numbering system. X11refers to the ver- sion of the network protocol that the X Window system is based on: Version 11was first released in 1988 and has been stable for 15 years, with only upwardcompatible additions to the coreX protocol, a recordofstability envied in computing. Formal releases of X started with X version 9 from MIT;the first commercial X products werebased on X version 10. The MIT X Consortium and its successors, the X Consortium, the Open Group X Project Team, and the X.OrgGroup released versions X11R3 through X11R6.6, beforethe founding of the X.OrgFoundation. Therewill be futuremaintenance releases in the X11R6.8.x series. However,efforts arewell underway to split the X distribution into its modular components to allow for easier maintenance and independent updates. We expect a transitional period while both X11R6.8 releases arebeing fielded and the modular release completed and deployed while both will be available as different consumers of X technology have different constraints on deployment. Wehave not yet decided how the modular X releases will be numbered. We encourage you to submit bug fixes and enhancements to bugzilla.freedesktop.orgusing the xorgproduct, and discussions on this server take place on <[email protected]>. -

Desktop Migration and Administration Guide

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Desktop Migration and Administration Guide GNOME 3 desktop migration planning, deployment, configuration, and administration in RHEL 7 Last Updated: 2021-05-05 Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Desktop Migration and Administration Guide GNOME 3 desktop migration planning, deployment, configuration, and administration in RHEL 7 Marie Doleželová Red Hat Customer Content Services [email protected] Petr Kovář Red Hat Customer Content Services [email protected] Jana Heves Red Hat Customer Content Services Legal Notice Copyright © 2018 Red Hat, Inc. This document is licensed by Red Hat under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. If you distribute this document, or a modified version of it, you must provide attribution to Red Hat, Inc. and provide a link to the original. If the document is modified, all Red Hat trademarks must be removed. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, the Red Hat logo, JBoss, OpenShift, Fedora, the Infinity logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Linux ® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java ® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS ® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL ® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. -

Solaris 10 807 Release Notes

Solaris 10 8/07 Release Notes Oracle Corporation 500 Oracle Parkway Redwood City, CA 94065 U.S.A. Part No: 820–1259–13 August 2007 Copyright © 2008, 2011, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. License Restrictions Warranty/Consequential Damages Disclaimer This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. Warranty Disclaimer The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. Restricted Rights Notice If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT RIGHTS Programs, software, databases, and related documentation and technical data delivered to U.S. Government customers are "commercial computer software" or "commercial technical data" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, the use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation shall be subject to the restrictions and license terms set forth in the applicable Government contract,and, to the extent applicable by the terms of the Government contract, the additional rights set forth in FAR 52.227-19, Commercial Computer Software License (December 2007). -

A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager Scott .J Griswold University of North Florida

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 1998 A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager Scott .J Griswold University of North Florida Suggested Citation Griswold, Scott .,J "A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager" (1998). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 95. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/95 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 1998 All Rights Reserved A JAVA IMPLEMENTATION OF A PORTABLE DESKTOP MANAGER by Scott J. Griswold A thesis submitted to the Department of Computer and Information Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer and Information Sciences UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER AND INFORMATION SCIENCES April, 1998 The thesis "A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager" submitted by Scott J. Griswold in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer and Information Sciences has been ee Date APpr Signature Deleted Dr. Ralph Butler Thesis Advisor and Committee Chairperson Signature Deleted Dr. Yap S. Chua Signature Deleted Accepted for the Department of Computer and Information Sciences Signature Deleted i/2-{/1~ Dr. Charles N. Winton Chairperson of the Department Accepted for the College of Computing Sciences and E Signature Deleted Dr. Charles N. Winton Acting Dean of the College Accepted for the University: Signature Deleted Dr. -

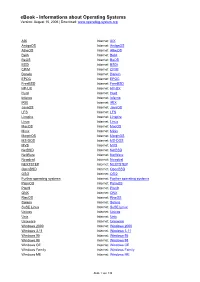

Ebook - Informations About Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download

eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org AIX Internet: AIX AmigaOS Internet: AmigaOS AtheOS Internet: AtheOS BeIA Internet: BeIA BeOS Internet: BeOS BSDi Internet: BSDi CP/M Internet: CP/M Darwin Internet: Darwin EPOC Internet: EPOC FreeBSD Internet: FreeBSD HP-UX Internet: HP-UX Hurd Internet: Hurd Inferno Internet: Inferno IRIX Internet: IRIX JavaOS Internet: JavaOS LFS Internet: LFS Linspire Internet: Linspire Linux Internet: Linux MacOS Internet: MacOS Minix Internet: Minix MorphOS Internet: MorphOS MS-DOS Internet: MS-DOS MVS Internet: MVS NetBSD Internet: NetBSD NetWare Internet: NetWare Newdeal Internet: Newdeal NEXTSTEP Internet: NEXTSTEP OpenBSD Internet: OpenBSD OS/2 Internet: OS/2 Further operating systems Internet: Further operating systems PalmOS Internet: PalmOS Plan9 Internet: Plan9 QNX Internet: QNX RiscOS Internet: RiscOS Solaris Internet: Solaris SuSE Linux Internet: SuSE Linux Unicos Internet: Unicos Unix Internet: Unix Unixware Internet: Unixware Windows 2000 Internet: Windows 2000 Windows 3.11 Internet: Windows 3.11 Windows 95 Internet: Windows 95 Windows 98 Internet: Windows 98 Windows CE Internet: Windows CE Windows Family Internet: Windows Family Windows ME Internet: Windows ME Seite 1 von 138 eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org Windows NT 3.1 Internet: Windows NT 3.1 Windows NT 4.0 Internet: Windows NT 4.0 Windows Server 2003 Internet: Windows Server 2003 Windows Vista Internet: Windows Vista Windows XP Internet: Windows XP Apple - Company Internet: Apple - Company AT&T - Company Internet: AT&T - Company Be Inc. - Company Internet: Be Inc. - Company BSD Family Internet: BSD Family Cray Inc. -

A Font Family Sampler

A Font Family Sampler Nelson H. F. Beebe Department of Mathematics University of Utah Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090, USA 11 February 2021 Version 1.6 To assist in producing greater font face variation in university disser- tations and theses, this document illustrates font family selection with a LATEX document preamble command \usepackage{FAMILY} where FAMILY is given in the subsection titles below. The body font in this document is from the TEX Gyre Bonum family, selected by a \usepackage{tgbonum} command in the document preamble, but the samples illustrate scores other font families. Like Computer Modern, Latin Modern, and the commercial Lucida and MathTime families, the TEX Gyre families oer extensive collections of mathematical characters that are designed to resemble their companion text characters, making them good choices for scientic and mathemati- cal typesetting. The TEX Gyre families also contain many additional spe- cially designed single glyphs for accented letters needed by several Euro- pean languages, such as Ð, ð, Ą, ą, Ę, ę, Ł, ł, Ö, ö, Ő, ő, Ü, ü, Ű, ű, Ş, ş, T,˚ t,˚ Ţ, ţ, U,˚ and u.˚ Comparison of text fonts Some of the families illustrated in this section include distinct mathemat- ics faces, but for brevity, we show only prose. When a font family is not chosen, the LATEX and Plain TEX default is the traditional Computer Mod- ern family used to typeset the Art of Computer Programming books, and shown in the rst subsection. 1 A Font Family Sampler 2 NB: The LuxiMono font has rather large characters: it is used here in 15% reduced size via these preamble commands: \usepackage[T1]{fontenc} % only encoding available for LuxiMono \usepackage[scaled=0.85]{luximono} \usepackage{} % cmr Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, aenean nulla tellus metus odio non maecenas, pariatur vitae congue laoreet semper, nulla adipiscing cursus neque dolor dui, faucibus aliquam quis. -

Modelsim SE Tutorial T-3

ModelSim® SE Tutorial Version 5.6d Published: 6/Aug/02 The world’s most popular HDL simulator T-2 ModelSim /VHDL, ModelSim /VLOG, ModelSim /LNL, and ModelSim /PLUS are produced by Model Technology™ Incorporated. Unauthorized copying, duplication, or other reproduction is prohibited without the written consent of Model Technology. The information in this manual is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of Model Technology. The program described in this manual is furnished under a license agreement and may not be used or copied except in accordance with the terms of the agreement. The online documentation provided with this product may be printed by the end-user. The number of copies that may be printed is limited to the number of licenses purchased. ModelSim is a registered trademark and ChaseX and TraceX are trademarks of Model Technology Incorporated. Model Technology is a trademark of Mentor Graphics Corporation. PostScript is a registered trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated. UNIX is a registered trademark of AT&T in the USA and other countries. FLEXlm is a trademark of Globetrotter Software, Inc. IBM, AT, and PC are registered trademarks, AIX and RISC System/6000 are trademarks of International Business Machines Corporation. Windows, Microsoft, and MS-DOS are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. OSF/Motif is a trademark of the Open Software Foundation, Inc. in the USA and other countries. SPARC is a registered trademark and SPARCstation is a trademark of SPARC International, Inc. Sun Microsystems is a registered trademark, and Sun, SunOS and OpenWindows are trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. -

System Administration

System Administration Varian NMR Spectrometer Systems With VNMR 6.1C Software Pub. No. 01-999166-00, Rev. C0503 System Administration Varian NMR Spectrometer Systems With VNMR 6.1C Software Pub. No. 01-999166-00, Rev. C0503 Revision history: A0800 – Initial release for VNMR 6.1C A1001 – Corrected errors on pg 120, general edit B0202 – Updated AutoTest B0602 – Added additional Autotest sections including VNMRJ update B1002 – Updated Solaris patch information and revised section 21.7, Autotest C0503 – Add additional Autotest sections including cryogenic probes Applicability: Varian NMR spectrometer systems with Sun workstations running Solaris 2.x and VNMR 6.1C software By Rolf Kyburz ([email protected]) Varian International AG, Zug, Switzerland, and Gerald Simon ([email protected]) Varian GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany Additional contributions by Frits Vosman, Dan Iverson, Evan Williams, George Gray, Steve Cheatham Technical writer: Mike Miller Technical editor: Dan Steele Copyright 2001, 2002, 2003 by Varian, Inc., NMR Systems 3120 Hansen Way, Palo Alto, California 94304 1-800-356-4437 http://www.varianinc.com All rights reserved. Printed in the United States. The information in this document has been carefully checked and is believed to be entirely reliable. However, no responsibility is assumed for inaccuracies. Statements in this document are not intended to create any warranty, expressed or implied. Specifications and performance characteristics of the software described in this manual may be changed at any time without notice. Varian reserves the right to make changes in any products herein to improve reliability, function, or design. Varian does not assume any liability arising out of the application or use of any product or circuit described herein; neither does it convey any license under its patent rights nor the rights of others. -

Oracle® Secure Global Desktop Platform Support and Release Notes for Release 4.7

Oracle® Secure Global Desktop Platform Support and Release Notes for Release 4.7 E26357-02 November 2012 Oracle® Secure Global Desktop: Platform Support and Release Notes for Release 4.7 Copyright © 2012, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Oracle and Java are registered trademarks of Oracle and/or its affiliates. Other names may be trademarks of their respective owners. Intel and Intel Xeon are trademarks or registered trademarks of Intel Corporation. All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. AMD, Opteron, the AMD logo, and the AMD Opteron logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Advanced Micro Devices. UNIX is a registered trademark of The Open Group. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. -

A Successor to the X Window System

Y: A Successor to the X Window System Mark Thomas <[email protected]> Project Supervisor: D. R¨uckert <[email protected]> Second Marker: E. Lupu <[email protected]> June 18, 2003 ii Abstract UNIX desktop environments are a mess. The proliferation of incompatible and inconsistent user interface toolkits is now the primary factor in the failure of enterprises to adopt UNIX as a desktop solution. This report documents the creation of a comprehensive, elegant framework for a complete windowing system, including a standardised graphical user interface toolkit. ‘Y’ addresses many of the problems associated with current systems, whilst keeping and improving on their best features. An initial implementation, which supports simple applications like a terminal emulator, a clock and a calculator, is provided. iii iv Acknowledgements Thanks to Daniel R¨uckert for supervising the project and for his help and advice regarding it. Thanks to David McBride for his assistance with setting up my project machine and providing me with an ATI Radeon for it. Thanks to Philip Willoughby for his knowledge of the POSIX standard and help with the GNU Autotools and some of the more obscure libc functions. Thanks to Andrew Suffield for his help with the GNU Autotools and Arch. Thanks to Nick Maynard and Karl O’Keeffe for discussions on window system and GUI design. Thanks to Tim Southerwood for discussions about possible features of Y. Thanks to Duncan White for discussions about the virtues of X. All company and product names are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Qtile Documentation Release 0.15.1

Qtile Documentation Release 0.15.1 Aldo Cortesi Apr 14, 2020 Contents 1 Getting started 1 1.1 Installing Qtile..............................................1 1.2 Configuration...............................................5 2 Commands and scripting 25 2.1 Commands API............................................. 25 2.2 Scripting................................................. 28 2.3 qshell................................................... 28 2.4 iqshell.................................................. 30 2.5 qtile-top.................................................. 31 2.6 qtile-run................................................. 31 2.7 qtile-cmd................................................. 31 2.8 dqtile-cmd................................................ 34 3 Getting involved 37 3.1 Contributing............................................... 37 3.2 Hacking on Qtile............................................. 38 4 Miscellaneous 43 4.1 Reference................................................. 43 4.2 Frequently Asked Questions....................................... 107 4.3 License.................................................. 108 Index 109 i ii CHAPTER 1 Getting started 1.1 Installing Qtile 1.1.1 Distro Guides Below are the preferred installation methods for specific distros. If you are running something else, please see In- stalling From Source. Installing on Arch Linux Stable versions of Qtile are currently packaged for Arch Linux. To install this package, run: pacman -S qtile Please see the ArchWiki for more information on -

README for X11R7.5 on Netbsd Rich Murphey David Dawes Marc Wandschneider Mark Weaver Matthieu Herrb Table of Contents What and Where Is X11R7.5?

README for X11R7.5 on NetBSD Rich Murphey David Dawes Marc Wandschneider Mark Weaver Matthieu Herrb Table of Contents What and Where is X11R7.5?..............................................................................................3 New OS dependent features...............................................................................................3 Configuring X for Your Hardware.....................................................................................4 Running X..............................................................................................................................5 Kernel Support for X............................................................................................................5 Rebuilding the X Distribution...........................................................................................7 Building New X Clients.......................................................................................................8 Thanks.....................................................................................................................................8 What and Where is X11R7.5? X11R7.5 is an Open Source version of the X Window System that supports several UNIX(R) and UNIX-like operating systems (such as Linux, the BSDs and Solaris x86) on Intel and other platforms. This version is compatible with X11R6.6, and is based on the XFree86 4.4.0RC2 code base, which, in turn was based on the X consortium sample implementation. See the Copyright Notice1. The sources for X11R7.5