Joseph Dj-Elzged Adam Buick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Embracing the Flux of Academic Librarianship to Co-Author Meaningful Change

Document Every thing determines everything Embracing the flux of academic librarianship to co-author meaningful change By Stephen Bales [Keynote address delivered at the 1st Annual Canadian Association of Professional Academic Librarians, Brock University, Saint Catharines, Ontario, May 26, 2014. The version herein has been modified from the original delivered at Brock University, and it also includes additional documentation and notes to further benefit the reader]. Introduction 137 I would like to thank the CAPAL Programme Committee for inviting me to speak today. I am honored to have this opportunity to share my ideas about academic librarianship with the members of the Canadian Association of Professional Academic Librarians. Today I want to discuss dialectical materialism as an alternative way of thinking about the academic library. It seems an appropriate topic for this conference, with its theme being the shifting landscapes of academic librarianship. Every one of us knows that the only true constant in the academic library is change. When I started library school in 2002, I think we were still at Web 1.0. Who knows what version we are on now? It’s a different world than it was just moments ago. Dialectical materialism has been around for nearly two Stephen Bales is Humanities and Social Sciences Librarian at Texas A&M University where he is subject librarian for communication & journalism, philosophy, religion, and anthropology. His research interests include the history and philosophy of libraries and librarianship and the professional identity of LIS workers. KEYWORDS: Philosophy of Library and Information Science; Professional Identity; Librarianship and Critical and Cultural Studies; Academic libraries; Dialectical materialism. -

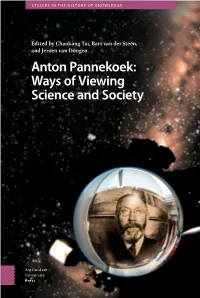

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. It aspires to offer accounts that cut across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, while being sensitive to how institutional circumstances and different scales of time shape the making of knowledge. Series Editors Klaas van Berkel, University of Groningen Jeroen van Dongen, University of Amsterdam Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: (Background) Fisheye lens photo of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector of Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo in action. (Foreground) Fisheye lens photo of a portrait of Anton Pannekoek displayed in the common room of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy. Source: Jeronimo Voss Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 434 9 e-isbn 978 90 4853 500 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984349 nur 686 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

University of Groningen De Dialectisch-Materialistische Filosofie Van

University of Groningen De dialectisch-materialistische filosofie van Joseph Dietzgen Schaaf, Jasper Willem IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1993 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Schaaf, J. W. (1993). De dialectisch-materialistische filosofie van Joseph Dietzgen. Kok/Agora. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 SUMMARY Joseph Dietzgen (1828-1888) Joseph Dietzgen was a philosopher and a tanner. At the congress for the 'our International in The Hague in 1872, Marx called him philosopher', the philosopher of proletarian social democracy; he also said once that Dietzgen was one of the most brilliant workers he knew. Dietzgen was a self-educatedphilo- sopher. On the political scene, he played a part in the notorious'Haymarket' affair in Chicago in 1886; one of the events which led to the introduction of annual First of May celebrations of the international labour movement. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zoeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) dr section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

361-Emerald Sabry-3611505 BIB 277..283

REFERENCES Abdel Naem, S. (1985). Moslimo Turkistan wa al-ghazw al-Sofyetti min khilal al-tarikh wal adab (Turkistan’s Muslims and the Soviet invasion in history and literature). Cairo: Dar Al- Ta’awan lil Taba’a wal Nashr. Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2006). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Adam Smith (1776). An Inquiry into the Nation and Cause of the Wealth of Nation. Glasgow Edition, Book IV. Al-Dirawi, O. (1990). Al-Harb Al-A’alamaya Al-Olaa (World War I). Beirut: Dar Al-Aalm lil- Malayien. Atkinson, A. B., & Morelli, S. (2014). Chartbook of economic inequality À Economic inequality over the long run. Retrieved from http://www.chartbookofeconomicinequality.com; internet. Accessed on May 1, 2015. Avineri, S. (1967). Marx and the intellectuals. Journal of the History of Ideas, 28(2), 269À278. (Apr. - Jun.): University of Pennsylvania Press.: Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/ 2708422; internet. Accessed on June 28, 2008. Baier, S., Dwyer, G. P., & Tamura, R. (2006). How important are capital and total factor productiv- ity for economic growth? Economic Inquiry, 44(1), 23À49. Bakunin, M. (1872). “On the International Workingmen’s Association and Karl Marx.” in Sam Dolgoff (1971) (edt.) Bakunin on Anarchy. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/refer- ence/archive/bakunin/works/1872/karl-marx.htm; internet. Accessed on August 11, 2016. Bakunin, M. (1873). “Critique of the Marxist theory of the State,” in Sam Dolgoff (1971) (edt.) Bakunin on Anarchy. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/bakunin/ works/1873/statism-anarchy.htm#s1; internet. -

Chapter One Do We Need Philosophy?

Chapter One Do we Need Philosophy? Before we start, you may be tempted to ask, "Well, what of it?" Is it really necessary for us to bother about complicated questions of science and philosophy? To such a question, two replies are possible. If what is meant is: do we need to know about such things in order to go about our daily life, then the answer is evidently no. But if we wish to gain a rational understanding of the world in which we live, and the fundamental processes at work in nature, society and our own way of thinking, then matters appear in quite a different light. Strangely enough, everyone has a "philosophy." For a philosophy is a way of looking at the world. We all believe we know how to distinguish right from wrong, good from bad. These are, however, very complicated issues which have occupied the attention of the greatest minds in history. When confronted with the terrible fact of the existence of events like the fratricidal war in the former Yugoslavia, the re-emergence of mass unemployment, the slaughter in Rwanda, many people will confess that they do not comprehend such things, and will frequently resort to vague references to "human nature." But what is this mysterious human nature which is seen as the source of all our ills, and is alleged to be eternally unchangeable? This is a profoundly philosophical question, to which not many would venture a reply, unless they were of a religious cast of mind, in which case they would say that God, in His wisdom, made us like that. -

Joseph Dietzgen, the Philosopher of Social Democracy

JOSEPH DIETZGEN, THE PHILOSOPHER OF SOCIAL DEMOCRACY. BY THE EDITOR. A MONG the philosophers of modern times Joseph Dietzgen is little l\. known partly because he was not a professional philosopher but, scientifically considered, a self-taught man, partly because his interest lay in the practical issues of life, for he was with all his soul a devoted adherent of the labor party. Hence he. has been called the philosopher of socialists or of social democracy. Joseph Dietzgen* was born December 9, 1828, at Blankenberg, a little town on the Sieg, a small river flowing into the Rhine a few miles above Cologne. The place is possessed of romantic traditions and a natural beauty. The ruins of an old castle are still standing, and the mountainous landscape is covered by woods and vineyards. His father was the owner of a tannery and in 1835 he moved to Uckerath, a small village in the neighborhood. In Uckerath Joseph attended the public school, and for a short time was sent to a Latin school in Oberpleis. He learned tanning in the tannery of his father, but he always had an open book with him while at work, for he was greatly interested in literature, political economy and philosophy. In 1848 he for the first time became conscious of his radical tenden- cies, and forthwith considered himself an outspoken socialist. In his philosophical ideas he was strongly under the influence of Feuer- bach, and in his socialist convictions he followed closely Marx and Engels. Carl Marx visited him at his home on the Rhine and became his friend. -

Beyond Marx and Mach: Aleksandr Bogdanov's Philosophy

BEYOND MARX AND MACH SOVIETICA PUBLICATIONS AND MONOGRAPHS OF THE INSTITUTE OF EAST -EUROPEAN STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF FRIBOURG/SWITZERLAND AND THE CENTER FOR EAST EUROPE, RUSSIA AND ASIA AT BOSTON COLLEGE AND THE SEMINAR FOR POLITICAL THEOR Y AND PHILOSOPHY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MUNICH Founded by J. M. BOCHENSKI (Fribourg) Edited by T. J. BLAKELEY (Boston), GUIDO KUNG (Fribourg),and NIKOLAUS LOBKOWICZ (Munich) Editorial Board Karl G. Ballestrem (Munich) Bernard Jeu (Lille) Helmut Dahm (Cologne) George L. Kline (Bryn Mawr) Richard T. DeGeorge (Kansas) T. R. Payne (Providence) Peter Ehlen (Munich) Friedrich Rapp (Berlin) Michael Gagern (Munich) Andries Sarlernijn (Eindhoven) Felix P. Ingold (St. Gall) James Scanlan (Columbus) Edward Swiderski (Fribourg) VOLUME 41 K. M. JENSEN University of Colorado BEYOND MARX AND MACH ALEKSANDR BOGDANOV'S Philosophy of Living Experience D. R:SIDEL PUBLISHING COMPANY DORDRECHT : HOLLAND / BOSTON: U.S.A. LONDON: ENGLAND Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Jensen, Kenneth Martin, 1944- Beyond Marx and Mach. (Sovietica ; v. 41) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Malinovskil, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich, 1873-1928. Filosofiili zhivogo opyta. 2. Philosophy. 3. Dialectical materialism. 4. Experience. I. Title. II. Series. B4249.M33F5434 197'.2 78-12916 ISBN-13: 978-94-009-9881-0 e-ISBN-13: 978-94-009-9879-7 ____-'0=-0=-:1: 10.1007/978-94-009-9879-7 Published by D. Reidel PubliShing Company, P.O. Box 17, Dordrecht, Holland Sold and distributed in the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico by D. Reidel Publishing Company, Inc. Lincoln Building, 160 Old Derby Street, Hingham, Mass. 02043, U.S.A. -

Karl Kautsky Ethics and the Materialist Conception of History (1906)

Karl Kautsky Ethics and the Materialist Conception Of History (1906) 1 Ethics and the Materialist Conception… Karl Kautsky Halaman 2 Content Author’s Preface I. Ancient and Christian Ethics II. The Ethical Systems of The Period of the Enlightenment III. The Ethic of Kant 1. The Criticism of Knowledge 2. The Moral Law 3. Freedom and Necessity 4. The Philosophy of Reconciliation IV. The Ethic of Darwinism 1. The Struggle for Existence 2. Self-Movement and Intelligence 3. The Motives of Self-Maintenance and Propagation 4. The Social Instinct V. The Ethics of Marxism 1. The Roots of the Materialist Conception of History 2. The Organization of the Human Society a. The Technical Development b. Technique and Method of Life c. Animal and Social Organization 3. The Changes in the Strength of the Social Instincts a. Language b. War and Property 4. The Influence of the Social Instincts a. Internationalism b. The Class Division 5. The Tenets of Morality a. Custom and Convention b. The System of Production and Its Superstructure c. Old and New d. The Moral Ideal Ethics and the Materialist Conception… Karl Kautsky Halaman 3 Preface Like so many other Marxist publications the present one owes its origin to a special occasion, it arose out of a controversy. The polemic in which I was involved last Autumn with the editors of Vorwärts brought me to touch on the question of their “ethical tendencies”. What I said, however, on this point was so often misunderstood by one side, and on the other brought me so many requests to give a more thorough and systematic exposition of my ideas on Ethics, that I felt constrained to attempt at least to give a short sketch of the development of Ethics on the basis of the materialist conception of history. -

First Socialist Schism Bakunin Vs

The First Socialist Schism Bakunin vs. Marx in the International Working Men’s Association Wolfgang Eckhardt Translated by Robert M. Homsi, Jesse Cohn, Cian Lawless, Nestor McNab, and Bas Moreel The First Socialist Schism Bakunin vs. Marx in the International Working Men’s Association The First Socialist Schism: Bakunin vs. Marx in the International Working Men’s Association Wolfgang Eckhardt © 2016 This edition published in 2016 by PM Press ISBN: 978-1-62963-042-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014908069 Cover: John Yates/Stealworks.com Layout: Jonathan Rowland PM Press P.O. Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 thoughtcrime ink C/O Black Cat Press 4508 118 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5W 1A9 Canada 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan www.thomsonshore.com This book has been made possible in part by a generous donation from the Anarchist Archives Project. I am profoundly grateful to Jörg Asseyer, Gianluca Falanga, Valerii Nikolaevich Fomichev, Frank Hartz, Gabriel Kuhn, Lore Naumann, Felipe Orobón Martínez, Werner Portmann, Michael Ryan, Andrea Stei, Hanno Strauß, and Michael Volk for their support and to the translators named above for their excellent job creating this English edition of my book. Contents 1 Bakunin, Marx, and Johann Philipp Becker 1 • The Alliance ‘request’ by Johann Philipp Becker (November 1868) • The Alliance joins the International (February–July 1869) • Becker’s position paper on the question of organisation (July 1869) 2 The International in Geneva and in -

Pico Della Mirandola Descola Gardner Eco Vernant Vidal-Naquet Clément

George Hermonymus Melchior Wolmar Janus Lascaris Guillaume Budé Peter Brook Jean Toomer Mullah Nassr Eddin Osho (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh) Jerome of Prague John Wesley E. J. Gold Colin Wilson Henry Sinclair, 2nd Baron Pent... Olgivanna Lloyd Wright P. L. Travers Maurice Nicoll Katherine Mansfield Robert Fripp John G. Bennett James Moore Girolamo Savonarola Thomas de Hartmann Wolfgang Capito Alfred Richard Orage Damião de Góis Frank Lloyd Wright Oscar Ichazo Olga de Hartmann Alexander Hegius Keith Jarrett Jane Heap Galen mathematics Philip Melanchthon Protestant Scholasticism Jeanne de Salzmann Baptist Union in the Czech Rep... Jacob Milich Nicolaus Taurellus Babylonian astronomy Jan Standonck Philip Mairet Moravian Church Moshé Feldenkrais book Negative theologyChristian mysticism John Huss religion Basil of Caesarea Robert Grosseteste Richard Fitzralph Origen Nick Bostrom Tomáš Štítný ze Štítného Scholastics Thomas Bradwardine Thomas More Unity of the Brethren William Tyndale Moses Booker T. Washington Prakash Ambedkar P. D. Ouspensky Tukaram Niebuhr John Colet Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī Panjabrao Deshmukh Proclian Jan Hus George Gurdjieff Social Reform Movement in Maha... Gilpin Constitution of the United Sta... Klein Keohane Berengar of Tours Liber de causis Gregory of Nyssa Benfield Nye A H Salunkhe Peter Damian Sleigh Chiranjeevi Al-Farabi Origen of Alexandria Hildegard of Bingen Sir Thomas More Zimmerman Kabir Hesychasm Lehrer Robert G. Ingersoll Mearsheimer Ram Mohan Roy Bringsjord Jervis Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III Alain de Lille Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud Honorius of Autun Fränkel Synesius of Cyrene Symonds Theon of Alexandria Religious Society of Friends Boyle Walt Maximus the Confessor Ducasse Rāja yoga Amaury of Bene Syrianus Mahatma Phule Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Qur'an Cappadocian Fathers Feldman Moncure D.