Public and Private Service Provision of Solid Waste Management in Kampala, Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Strategies and Contested Dominance in Kampala

ESID Working Paper No. 146 Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala Nansozi K. Muwanga1, Paul I. Mukwaya2 and Tom Goodfellow3 June 2020 1 Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected]. 3 Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield, UK Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-56-9 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala. Abstract Although Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) has dominated Uganda’s political scene for over three decades, the capital Kampala refuses to submit to the NRM’s grip. As opposition activism in the city has become increasingly explosive, the ruling elite has developed a widening range of strategies to try and win urban support and constrain opposition. In this paper, we subject the NRM’s strategies over the decade 2010-2020 to close scrutiny. We explore elite strategies pursued both from the ‘top down’, through legal and administrative manoeuvres and a ramping up of violent coercion, and from the ‘bottom up’, through attempts to build support among urban youth and infiltrate organisations in the urban informal transport sector. Although this evolving suite of strategies and tactics has met with some success in specific places and times, opposition has constantly resurfaced. -

Sales Stripes

Future Initiatives & Charitable Group Kabalagala, Kampala |Reg No: MAK/19/201|1015964727 +256772122854|+256777114616|+256787275162 www.ficouganda.com|[email protected] PROJECT PROPOSAL FOR PEOPLE CONCERNED CHILDREN” S PROJECT NURSERY AND PRIMARY SCHOOL LOCATED IN KABALAGALA, KAMPALA CITY COUNCIL AUTHORITY IN KAMPALA DISTRICT - UGANDA OCTOBER 2019 PEOPLE CONCERNED CHILDREN’S PROJECT e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] 2 EXECUTIVE STATEMENT The Project Offices are located 3 miles (4.5 kilometers) in Kabalagala, Makindye Division, Kampala City Council Authority, and Kampala District along Tubuga Road Households are benefiting directly and indirectly through impar knowledge to their young ones to create awareness and competitiveness on post levels and market for their food staffs respectively. The source of funds to sustain the project has been entirely People Concerned Children’s Project. The school is already established but still lack many premises. However, the school has land which can be used to establish a fully-fledged compass. The school lacks several amenities and if many of these would be rectified, there is a very big likelihood that education standards in the Community and the area would improve greatly. The area is a heavily populated urban informal settlement place characterized by substandard housing and low standards of living. These communities are defined by high level of poverty, low income, inadequate living conditions and sub-standard facilities. Other characteristics are: • Inadequate access to safe water • Inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure • Poor structural quality of housing • Overcrowding It is essential that at least 60 percent of the urban population lives in slums of which Kikubamutwe located in Kabalagala is one of them. -

“Pressing the Right Buttons”

0013EP “Pressing the Right Buttons” Jennifer Musisi for New City Leadership Epilogue ERIC WEINBERGER AND JORRIT DE JONG As head of the new Kampala Capital City Authority, Jennifer Musisi set her goals high: to increase revenue, fight corruption, and build the City’s financial capacity by creating a sustainable system of fee and tax collection, all while improving overall service delivery. She knew there would be serious resistance to change coming from populist politicians in both government and opposition (in Parliament, in Kampala, and in the KCCA). There would be intransigence from all directions: from her own officials, those in other agencies, powerful commercial forces including the many private collection agents now thrown out of business, and from hundreds of thousands of ordinary Kampalans who struggled to make a living, many of them as transit drivers, street vendors, or other kinds of traders, usually unregulated. Increasing Revenues Musisi’s success at improving collections in Kampala was practically immediate and continued for the first half of her nearly eight years in office. Over those four years, beginning with the 2011-12 fiscal year, overall own-source revenue (OSR) jumped 198 percent: KCCA own-source revenue (OSR) in billions of Ugandan shillings 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 30 39.5 55.06 70.1 80.4 85 85.75 Between FY 2012 and FY 2014, property tax revenues rose from UGX 11 billion to UGX 24 billioni ($3.3 million to $7.2 million), and parking fees (now including taxis) rose from UGX 5 billion to UGX 16 billion ($1.5 million to $4.8 million). -

Kampala Cholera Situation Report

Kampala Cholera Situation Report Date: Monday 4th February, 2019 1. Summary Statistics No Summary of cases Total Number Total Cholera suspects- Cummulative since start of 54 #1 outbreak on 2nd January 2019 1 New case(s) suspected 04 2 New cases(s) confirmed 54 Cummulative confirmed cases 22 New Deaths 01 #2 3 New deaths in Suspected 01 4 New deaths in Confirmed 00 5 Cumulative cases (Suspected & confirmed cases) 54 6 Cumulative deaths (Supected & confirmed cases) in Health Facilities 00 Community 03 7 Total number of cases on admission 00 8 Cummulative cases discharged 39 9 Cummulative Runaways from isolation (CTC) 07 #3 10 Number of contacts listed 93 11 Total contacts that completed 9 day follow-up 90 12 Contacts under follow-up 03 13 Total number of contacts followed up today 03 14 Current admissions of Health Care Workers 00 13 Cummulative cases of Health Care Workers 00 14 Cummulative deaths of Health Care Workers 00 15 Specimens collected and sent to CPHL today 04 16 Cumulative specimens collected 45 17 Cummulative cases with lab. confirmation (acute) 00 Cummulative cases with lab. confirmation (convalescent) 22 18 Date of admission of last confirmed case 01/02/2019 19 Date of discharge of last confirmed case 02/02/2019 20 Confirmed cases that have died 1 (Died from the community) #1 The identified areas are Kamwokya Central Division, Mutudwe Rubaga, Kitintale Zone 10 Nakawa, Naguru - Kasende Nakawa, Kasanga Makindye, Kalambi Bulaga Wakiso, Banda Zone B3, Luzira Kamwanyi, Ndeba-Kironde, Katagwe Kamila Subconty Luwero District, -

Urban Land Governance, Housing and Public Open Spaces

URBAN THINKERS’ DIALOGUES Community Engagements On The City We Need UCOBAC Uganda Community Based Association for Women Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung - Uganda Office and Children Welfare 5B, John Babiiha Avenue Plot 17, Robert Mugabe Road, P.O.Box 3860 Kampala, Uganda Kampala Sessions - Brief Mbuya Zone 1 Kampala, Uganda Phone: +256 393 264 565 Phone: +256 755 949959 Email: fes[at]fes-uganda.org Email: [email protected] www.fes-uganda.org Twitter: @ucobac Facebook: ucobac1990 www.ucobac.org THEME: Pro-poor and gender responsive urban land governance for increased security of tenure and equitable access to land, housing and public open spaces in cities. UCOBAC Urban Land Governance, Housing and Public Open Spaces The City We Need – Urban Thinkers Dialogues Urban Thinkers Dialogues In 2017 Uganda Community Based Association for Women and Children Welfare (UCOBAC) in partnership with Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) organised five 1-2 day dialogues, engaging more than 600 participants in Kampala’s five divisions of Central, Kawempe, Makindye, Nakawa and Rubaga. The dialogues engaged multiple community representatives and discussed local experiences and problems around land, housing and public open spaces. This briefing summarises the findings and recommendations derived from these public dialogues. ------------------------------ Urban Thinkers’ Dialogues ------------------------------ 2 Key findings and recommendations Large-scale corruption remains a major obstacle for developing and providing land security, affordable housing and public open spaces (POS), especially for the urban poor. Effective, just and transparent urban land administration, affordable and adequate housing to all, and the provision of sufficient public open spaces must be recognised as crucial socio- economic factors in the development of Kampala city and Uganda’s economy. -

Approved Bodaboda Stages

Approved Bodaboda Stages SN Division Parish Stage ID X-Coordinate Y-Coordinate 1 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1001 32.563999 0.317146 2 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1002 32.564999 0.317240 3 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1003 32.566799 0.319574 4 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1004 32.563301 0.320431 5 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1005 32.562698 0.321824 6 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1006 32.561100 0.324322 7 CENTRAL DIVISION INDUSTRIAL AREA 1007 32.610802 0.312010 8 CENTRAL DIVISION INDUSTRIAL AREA 1008 32.599201 0.314553 9 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1009 32.565701 0.325353 10 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1010 32.569099 0.325794 11 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1011 32.567001 0.327003 12 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1012 32.571301 0.327249 13 CENTRAL DIVISION KAMWOKYA II 1013 32.583698 0.342530 14 CENTRAL DIVISION KOLOLO I 1014 32.605900 0.326255 15 CENTRAL DIVISION KOLOLO I 1015 32.605400 0.326868 16 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1016 32.567101 0.305112 17 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1017 32.563702 0.306650 18 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1018 32.565899 0.307312 19 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1019 32.567501 0.307867 20 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1020 32.567600 0.307938 21 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1021 32.569500 0.308241 22 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1022 32.569199 0.309950 23 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1023 32.564800 0.310082 24 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1024 32.567600 0.311253 25 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1025 32.566002 0.311941 26 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1026 32.567501 0.314132 27 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1027 32.565701 0.314559 28 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1028 32.566002 0.314855 29 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD -

Slum Settlement Profile Comes at an Opportune Time – a Time When the City of Kampala Is Experiencing Unprecedented Growth in the History of Uganda

FOREWORD This Slum Settlement Profile comes at an opportune time – a time when the city of Kampala is experiencing unprecedented growth in the history of Uganda. This growth and expansion is visible through the mushrooming of informal settlements across the different divisions of Kampala, especially in the low-lying areas of the city. This expansion has definitely exerted enormous pressure on land, with the poor occupying open spaces and the rich pushing the poor out of settlements for commercial and more formalised developments. The urban infrastructure (services and utilities) has not been spared as many residents demand for better quality water, sewer/ sanitation facilities, electricity, roads, security, and proper solid waste management systems. While the city still grapples with serving the existing communities, there are thousands that are flocking to the city in search of employment opportunities and better services. The invisible challenge for both the city and the communities has been lack of data/ information concerning the informal settlements, leading to a very wide gap between the plans and the priorities for the slum residents. The variables looked at in this Slum Profile include, among other factors, Security of Tenure, Housing, Water and Sanitation, Economic Activities, Accessibility, Drainage, and Solid Waste Management. Perhaps, the most outstanding and profound aspect is that this Slum Profile is not a collection of information from lawyers, teachers, doctors, or academicians, but rather ideas from the real slum dwellers who interface with the day-to- day challenges of slum life. KAMPALA PROFILES: MAKINDYE Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 PROFILE METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 3 A. -

Second Kampala Institutional & Infrastructure Development Project

Second Kampala Institutional & Infrastructure Development Project By: JOSEPHINE NALUBWAMA MUKASA Uganda; Kampala City MAP OF AFRICA: LOCATION OF UGANDA UGANDA KAMPALA CITY • Located in Kampala district -North of Lake Victoria • Comprised of five Divisions, Kampala Central Division, Kawempe, Makindye, Nakawa, and Lubaga Division. • Size: 189Km2 • Population: 1. 5million (night) Over 3 million (Day) CITY ADMINISTRATION STRUCTURE KAMPALA INFRASTRUCTURE AND INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Improving mobility, FLOODING IN THE CITY CONGESTION ON THE ROADS connectivity in the city POOR DRAINAGE SYSTEM NON MOTORABLE ROADS OVERVIEW OF THE PROJECT • Goal: To enhance infrastructure and Institutional capacity of the city and improve urban mobility for inclusive economic growth. • Project Duration: 5 years (FY2014 – FY 2019) • Project Financing: The project is financed through an Investment Project Financing (IPF) facility of US$175 million (equivalent) IDA Credit and GoU/KCCA counterpart funding of US$8.75 million equivalents. The total project financing is US$183.75 million • Stake holders: Communities, World Bank, Government of Uganda, Utility companies KEY ISSUES OF PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION • Delays in securing right of way due to contestation of the approved values, mortgaged titles, Titles with Caveats, absent land lords among others; • Delay in securing land for resettlement of project affected persons; • Uncooperative property owners in providing pertinent information; • Sometimes poor political atmosphere – the different political campaigns -

Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities KAMPALA, UGANDA

Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities KAMPALA, UGANDA Urban Environmental Profile Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities KAMPALA, UGANDA Urban Environmental Profile COPYRIGHT © 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. September 2015 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Publishing and Knowledge Division, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, -

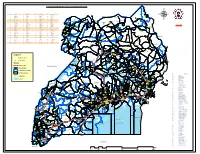

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Acknowledgement: the Authors Are Grateful for Financial Support from the Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Qu

PARTNERSHIPS FOR HEALTHY DIETS AND NUTRITION IN URBAN AFRICAN FOOD SYSTEMS – EVIDENCE AND STRATEGIES “THE KANYANYA FOOD CHALLENGE – FOOD SYSTEMS MAPPING” PROGRESS REPORT DELIVERABLE WP1: NOURICITY - KAMPALA Vincent Linderhof, Youri Dijkxhoorn (both Wageningen Economic Research), Joel Onyango (BoP innovation centre), Andrea Fongar (Bioversity International), and Martha Nalweyiso Date of the report 31-12-2019 Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful for financial support from the Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (grant number BO-43-003.02-009 as part of LEAP-Agri program), and the flagship program Food Systems for Healthier Diets of the CGIAR program Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH). 1 | The Kanyanya food challenge Contents Glossary ............................................................................................................................ 3 List of figures ..................................................................................................................... 5 List of tables ...................................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 7 2 Desk study ................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 2.1 Description of Kampala .................................................................................... 8 -

2009 – Kivulu, Kampala

KIVULU PROCESS AND PROJECT 1 AAR 4525 URBAN ECOLOGICAL PLANNING - TRONDHEIM 2009 in coorporation with Makerere University with financial support from A REPORT ON A FIELDWORK CARRIED OUT IN KAMPALA, UGANDA by ANDRÉ ALMEIDA SI CONG LIU STYRKAAR HUSTVEIT GURO KRISTINE VENGEN and ZAHRA KYOBUTUNGI (falling ill during the fieldwork) together with FREDERICK JAY MUGISA LUCK NANSEREKO from Makerere University Table of Contents Preface ...09 Introduction ...11 Time line ...12 PART I - THEORY AND FACTS Urban Challenges in the Global South ...16 Kivulu - Location ...20 - History ...20 - Governance ...21 - Economic Activity ...22 PART II - UNDERSTANDING KIVULU The Fieldwork Research - Introduction ...26 - The Interviews ...28 - Meetings ...32 - Observation ...35 - Photographs ...35 - Maps ...37 - Processing of the Information Gathered ...37 Assessment of Findings, and a Growing Understanding of Kivulu - Introduction ...38 - The Issue of Land and Urban Development ...39 - Unclear Community ...42 PART III - ACTING IN KIVULU Acting in Kivulu - The Reality Clash ...47 - Shift of Focus - the Community Centre as a process ...49 - The Creation of an Entry Point and ACTogether ...52 - The Saving Scheme and Stepping Off ...55 - Our Role and a Drum ...57 - Introduction of the Community Center to the Saving Scheme ...59 - The Design and the ISSB ...62 Securing the Implementation and a Description on the Status Now ...67 Reflections ...71 Bibliography ...74 Appendix - Interviews ...78 - Information from ACTogether ...97 - Drawings ...106 8 PREFACE it difficult to include in the work. This report is a description of the work done in the settlement Also, in this edition of the report, an executive summary has of Kivulu in Kampala, Uganda by some of the students follow- been left out that will be added in later editions.