Contemplative Or Centring Prayer – by Helen Friend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Russian Orthodoxy and Women's Spirituality In

RUSSIAN ORTHODOXY AND WOMEN’S SPIRITUALITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA* Christine D. Worobec On 8 November 1885, the feast day of Archangel Michael, the Abbess Taisiia had a mystical experience in the midst of a church service dedicated to the tonsuring of sisters at Leushino. The women’s religious community of Leushino had recently been ele vated to the status of a monastery.1 Conducting an all-women’s choir on that special day, the abbess became exhilarated by the beautiful refrain of the Cherubikon hymn, “Let us lay aside all earthly cares,” and envisioned Christ surrounded by angels above the iconostasis. She later wrote, “Something was happening, but what it was I am unable to tell, although I saw and heard every thing. It was not something of this world. From the beginning of the vision, I seemed to fall into ecstatic rapture Tears were stream ing down my face. I realized that everyone was looking at me in astonishment, and even fear....”2 Five years later, a newspaper columnistwitnessedasceneinachurch in the Smolensk village of Egor'-Bunakovo in which a woman began to scream in the midst of the singing of the Cherubikon. He described “a horrible in *This book chapter is dedicated to the memory of Brenda Meehan, who pioneered the study of Russian Orthodox women religious in the modern period. 1 The Russian language does not have a separate word such as “convent” or nunnery” to distinguish women’s from men’s monastic institutions. 2 Abbess Thaisia, 194; quoted in Meehan, Holy Women o f Russia, 126. Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture. -

Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a Division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by Permission

WO M E N I N T H E MISSION OF THE CHURCH Their Opportunities and Obstacles throughout Christian History Leanne M. Dzubinski and Anneke H. Stasson K Leanne Dzubinski & Anneke Stasson, Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by permission. _DzubinskiStasson_WomenMissionChurch_JH_wo.indd 3 1/27/21 3:29 PM CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction: Women in Ministry Is Not a Twentieth- Century Phenomenon 1 PART 1 WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN THE EARLY CHURCH 1. Patrons, Missionaries, Apostles, Widows, and Martyrs 13 2. Virgins, Scholars, Desert Mothers, and Deacons 35 PART 2 WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND THE MIDDLE AGES 3. Mothers, Sisters, Empresses, and Queens 59 4. Medieval Nuns 83 5. Beguines and Mystics 105 PART 3 WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP SINCE THE REFORMATION 6. Women Preachers in America 125 7. Social Justice Activists 145 vii Leanne Dzubinski & Anneke Stasson, Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by permission. _DzubinskiStasson_WomenMissionChurch_JH_wo.indd 7 1/27/21 3:29 PM viii Contents 8. Denominational Missionaries and Bible Women 161 9. Faith Missionaries, Evangelists, and Church Founders 183 Conclusion: Women’s Leadership in the Church 203 Bibliography 215 Index 233 Leanne Dzubinski & Anneke Stasson, Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by permission. _DzubinskiStasson_WomenMissionChurch_JH_wo.indd 8 1/27/21 3:29 PM INTRODUCTION Women in Ministry Is Not a Twentieth- Century Phenomenon (Anneke) am sitting in a guesthouse at a monastery in Michigan. -

In the Heart of the Desert: the Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers

World Wisdom In the Heart of the Desert: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers In the Heart of the Desert: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers, by Rev. Dr. John Chryssavgis, brings to life the timeless message of the founders of Christian Monasticism. Seeking God through silence and prayer, these fourth and fifth century Christian ascetics still have much to teach us about the nature of the human soul. The words of spiritual counsel (Apophthegmata, from the original Greek), reflect the imprint of eternity and with the insightful commentary of Rev. John Chryssavgis, the ancient teachings of these early Fathers and Mothers are drawn into sharp focus and made more relevant for the contemporary reader. In the Heart of the Desert portrays several key figures of the early Christian monastic communities in the stark deserts of Egypt and Syria. This book, unlike many earlier studies, also includes one of the Desert Mothers, Amma Syncletica. In addition, for the first time in English, Rev. Dr. Chryssavgis offers a translation of the fifth-century text, the Reflections of Abba Zosimas, which played an important part in the development of the sayings of the Desert Fathers. The words of these early Christian monks have influenced the lives of numerous people over many centuries, from Saint Augustine to Thomas Merton, and continue to offer their compelling stories and ideas to people today. What is being said about In the Heart of the Desert? “A beautiful and sensitive account of the lives and spirituality of the early Christian desert monastics. Chryssavgis’ treatment of these strange, compelling figures is marked by an uncommon depth of understanding; under his discerning gaze, the world of the desert monastics comes alive for the reader. -

PREFACE “We Are Coming out of the Desert” — St

PREFACE “We are Coming Out of the Desert” — St. Anthony of Beaconsfield In one sense this present book is a complement to my previous title The Tumbler of God: Chesterton as Mystic.1 In that book I attempted to demonstrate that one of the main sources of G.K. Chesterton’s sense of joy and wonder was a genuine mystical grace that enabled him to experience everything coming forth at every moment from the creative hand of God. For those not very familiar with Chesterton, or who have a rather superficial knowledge of his writings, they could have the impression that he didn’t see any evil in the world. However, to correct such a notion, I want to emphasize in this book his belief in, and pugnacious battle with, the devil. Of course, he also believed in the evil present in the human heart, and in the “problem of evil” which philosophers try to explain. These last two have been treated in Mark Knight’s Chesterton and Evil,2 and we will be considering some of his insights below. My emphasis is explicitly on Satan. In my research for this book I have often found that treatment of the devil in major works about Chesterton often lacking. For 1 In Canada, The Tumbler of God (Justin Press: Ottawa, Ontario, 2012). Outside Canada (Angelico Press: Brooklyn, New York, 2013). 2 Mark Knight, Chesterton and Evil (Fordham University Press: New York, 2004). xvii xviii Jousting with the Devil example, we have all profited very much from Aidan Nichols’ G.K. Chesterton, Theologian;3 and an increasing number of people will delight in Ian Ker’s recent biography, G.K. -

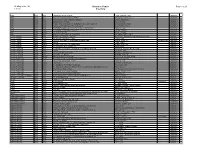

Excel Catalogue

Saint John the Evangelist Parish Library Catalogue AUTHOR TITLE Call Number Biography Abbott, Faith Acts of Faith: a memoir Abbott, Faith Abrams, Bill Traditions of Christmas J Abrams Abrams, Richard I. Illustrated Life of Jesus 704.9 AB Accattoli, Luigi When a Pope ask forgiveness 232.2 AC Accorsi, William Friendship's First Thanksgiving J Accorsi Biography More, Thomas, Ackroyd, Peter Life of Thomas More Sir, Saint Adair, John Pilgrim's Way 914.1 AD Cry of the Deer: meditations on the hymn Adam, David of St. Patrick 242 AD Adoff, Arnold Touch the Poem J 811 AD Aesop Aesop for Children J 398.2 AE Parish Author Ahearn, Anita Andreini Copper Range Chronicle 977.499 AH Curse of the Coins: Adventures with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Pope no. Ahern Dianne 3 J Ahern Secrets of Siena: Adventures with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Pope no. Ahern Dianne 4 J Ahern Break-In at the Basilica: Adventrues with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Ahern, Dianne Pope no.2 J Ahern Lost in Peter's Tomb: Adventures with Sister Philomena, Special Agent to the Ahern, Dianne Pope no. 1 J Ahern Ahern, Dianne Today I Made My First Communion J 265.3 AH Ahern, Dianne Today I Made My First Reconciliation J 265.6 AH Ahern, Dianne Today I was Baptized J 264.02 AH Ahern, Dianne Today Someone I Loved Passed Away J 265.85 AH Ahern, Dianne Today we Became Engaged 241 AH YA Biography Ahmedi, Farah Story of My Life Ahmedi Aikman, David Great Souls 920 AK Akapan, Uwem Say You're one of the Them Fiction Akpan Biography Gruner, Alban, Francis Fatima Priest Nicholas Albom, Mitch Five people you meet in Heaven Fiction Albom Albom, Mitch Tuesdays with Morrie 378 AL Albom,. -

ASCETICISM and WOMEN's FREEDOM in CHRISTIAN LATE ANTIQUITY: Some Aspects of Thecla Cults and Egeria's Journey

ASCETICISM AND WOMEN'S FREEDOM IN CHRISTIAN LATE ANTIQUITY: Some Aspects of Thecla Cults and Egeria's Journey Hiroaki ADACHI* How women involved with history? Recently, there have been many attempts to scrutinize the women's experiences in history. ln this article, I try to reconstruct the women's traditions in late antique Christian society in the Mediterranean World, by reading some written materials on women, especially about Saint Thecla and a woman pilgrim Egeria. First of all, I briefly summarize the new tide of the reinterpretations of the late antique female hagiographies. In spite of the strong misogynistic tendency of the Church Fathers, Christian societies in late antiquity left us a vast amount of the Lives of female saints. We can easily realize how some aristocratic women had great influence on the society through ascetic renunciation. However, we should bear in mind the text was distorted by male authors. On the account of the problem, I pick out the legendary heroine Thecla. She is the heroine of an apocryphal text called the Acts of Paul and Thecla. In the Acts, she is really independent. She abandons her fiance and her mother and follows Paul in the first part. On the second part, Paul disappears and she baptizes herself in the battle with wild beasts. At that time, crowd of women encourage her. Though there have been many disputations about the mythological Acts, all scholars agree with the "fact" that late antique women accepted the Thecla Acts as the story for themselves. In spite of serious condemnation of Tertullian, Thecla cults flourished throughout the late antique times and a woman pilgrim Egeria visited her shirine Hagia Thecla in Asia Minor. -

Contemplating Creation a Lenten Journey with the Mystics and Our Common Home

March 18–24, 2017 FOR THE DIOCESE OF BURLINGTON Contemplating Creation A Lenten Journey with the Mystics and Our Common Home While driving to an appointment recently, I decided to meander by taking a country road. As I rounded the bend, the snowcapped ridge of Mt. Mansfield revealed itself, illuminated by the morning light, radiating the beauty of creation. A lone hawk glided on the winds as I heard the call of the glistening white snow owl perched on a branch near the road. Breathless, I stopped to witness while offering a prayer of gratitude. God caught my attention on the journey in the daily. relationship with Jesus. As our Lenten scriptures remind us, “God looked at everything God had made, Christ went “into the dessert” to listen, witness and renew and found it very good.” his spirit. Christian Mystics, from the desert mothers and fathers to our present day saints, model this example, pointing — Gen 1:31 towards a profound and deep Mystery of relationship with God in and through all of creation. In “Care for Our Common Home” Pope Francis reminds You’re invited to join the 4 part series “Contemplating us of the sanctity of the earth. “The Spirit of God has Creation: A Lenten Journey with the Christian Mystics” in- filled the world with possibilities, and therefore, from the formed by Catholic teaching and the wisdom of Pope Francis’ very heart of things, something new can emerge. Nature is words in “Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home.” nothing other than a certain kind of art, namely God’s art, The series is offered at St. -

New Monasticism

A publication of the INTERCOMMUNITY PEACE & JUSTICE CENTER NO. 117 / WINTER 2018 New Monasticism The topic of this issue of A Matter of Spirit is the “New Monasticism.” What do you Living Monasticism think of when you hear the By Christine Valters Paintner journeying with others who are also strug- word “monastic?” Do you gling against busyness, debt and divisive- picture a solitary monk in a Over the last twenty years there has been ness. hermitage far from town? a great renewal of interest in the monastic The root of the word monk is monachos, Do you think of a medieval life, but this time from those who find them- which means single-hearted. To become a community reciting prayers in Latin? Or do you think of selves wanting to live outside the walls of the monk in the world means to keep one’s focus a group of millennials living cloister. It was this desire that led me fifteen on the love at the heart of everything. This is and working together today? years ago to become a Benedictine oblate. available to all of us, regardless of whether Each of these, and more, are Becoming an oblate means making a com- we live celibate and cloistered, partnered and expressions of the monastic mitment to live out the Benedictine charism raising a family or employed in business. impulse, a desire to connect in daily life, at work, in a marriage and fam- The three main sources I draw upon to deeply to a life of prayer and ily, and in all the other ways ordinary people sustain me in this path are the Rule of Bene- service in community with interact with the world on a daily basis. -

Angels Bible

ANGELS All About the Angels by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P. (E.D.M.) Angels and Devils by Joan Carroll Cruz Beyond Space, A Book About the Angels by Fr. Pascal P. Parente Opus Sanctorum Angelorum by Fr. Robert J. Fox St. Michael and the Angels by TAN books The Angels translated by Rev. Bede Dahmus What You Should Know About Angels by Charlene Altemose, MSC BIBLE A Catholic Guide to the Bible by Fr. Oscar Lukefahr A Catechism for Adults by William J. Cogan A Treasury of Bible Pictures edited by Masom & Alexander A New Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture edited by Fuller, Johnston & Kearns American Catholic Biblical Scholarship by Gerald P. Fogorty, S.J. Background to the Bible by Richard T.A. Murphy Bible Dictionary by James P. Boyd Bible History by Ignatius Schuster Christ in the Psalms by Patrick Henry Reardon Collegeville Bible Commentary Exodus by John F. Craghan Leviticus by Wayne A. Turner Numbers by Helen Kenik Mainelli Deuteronomy by Leslie J. Hoppe, OFM Joshua, Judges by John A. Grindel, CM First Samuel, Second Samuel by Paula T. Bowes First Kings, Second Kings by Alice L. Laffey, RSM First Chronicles, Second Chronicles by Alice L. Laffey, RSM Ezra, Nehemiah by Rita J. Burns First Maccabees, Second Maccabees by Alphonsel P. Spilley, CPPS Holy Bible, St. Joseph Textbook Edition Isaiah by John J. Collins Introduction to Wisdom, Literature, Proverbs by Laurance E. Bradle Job by Michael D. Guinan, OFM Psalms 1-72 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Psalms 73-150 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther by James A. -

Resource Center New 2012

St. Mary of the Hill Resource Center Page 1 of 24 5-11-05 Inventory Bible Adult Book Beginning Biblical Studies Frigge, Marielle, OSB Card/label Bible Adult Book How Do Catholics Read the Bible? Harrington, Daniel J S.J. Card/label Bible Adult Book Introduction to Old Testament Wisdom Cresko, Anthony R. Card/label Bible Adult Book Making Sense of Paul Wiles, Virgina Card/label Bible Adult Book People of the Covenant- An Invitation to the Old Testament Bergant, Dianne CSA Card/label Bible Adult Book Psalms and Readings for Every Season Kraus S.T.D., James Card/label Bible Adult Book The Bible Blueprint- A Catholic's Guide to God's Word Paprocki, Joe Card/label * Bible Adult Book The Gospel of Matthew- Volume 2 Barclay, William Card/label Bible Adult BOok The Letters of Paul Roetzel, Calvin Card/label Bible Adult Book Who is Jesus? Why is He Important Harrington, Daniel J S.J. Card/label Church History Adult Book A History of Christian Tradition McGonigle, Thomas D. and Quigley, James F. Card/label Church History Adult Book Archbishop Timothy M. Dolan Lucero, Sam Card/label Church History Adult Book Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe- includes map Mueller Media, Inc. includes map Card/label Church History Adult Book Sisters Fialka, John J. Card/label Church History Adult Video St. Mary of the Hill 75th Anniversary St Mary of the Hill Card/label Church History Adult Book The Forgotten Desert Mothers Swan, Laura Card/label Church Teaching Adult Book Immaculate Conception:Panorama of the Marian Doctrine Piacentini, Ernesto, O.F.M. -

Desert Fathers & Mothers

The Contemplative Society PO Box 23031 Cook St. RPO, Victoria BC V8V 4Z8 Canada 250.381.9650 [email protected] www.contemplative.org DESERT FATHERS & MOTHERS Teaching by Cynthia Bourgeault Recorded March 8-14, 2014 Redemptorist Renewal Center, Tucson Arizona 12 CD set (approx. 15 hours) As this is a LIVE recording you may notice some audio variability and background noise. Be prepared to discover in this set of teachings the original desert fathers and mothers in a whole new way – as Christian disciples and sages. Cynthia begins by exploring how the desert is a perfect setting both physically and metaphorically for the spiritual seeker. You are invited to recognize your own personal desert and to work within its constrictions as you walk your individual path toward the divine. Cynthia quickly dispels the common misconceptions about the early desert fathers and mothers as rejecting the body and engaging in self-harming practices. Instead, the desert tradition is revealed as a model for present-day wisdom schools. The early Christian desert dwellers are seen as being dedicated to becoming transformed humans in the way of Christ – balancing asceticism and temperance, solitude and community, right dominion and humility, equanimity and passion, vigilance and nonattachment. Their practices and teachings serve as a guide today for bridging the material realm and the intense realm of deep prayer and for participating in the unfolding of a new humanity. References for this recorded teaching: Texts directly used during the teaching sessions: Athanasius: The Life of Antony and the Letter to Marcellinus. Robert C. Gregg (trans.) Ward, Benedicta: The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetical Collection.