PREFACE “We Are Coming out of the Desert” — St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

BULLETIN IS Jan

ST. ELIJAH ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN CHURCH 15000 N. May, Oklahoma City, OK 73134 Church Office: 755-7804 Church Website: www.stelijahokc.com Church Email: [email protected] JANUARY 17, 2021 Issue 33 Number 3 Venerable and God-bearing Father Anthony the Great & TwelFth Sunday oF Luke; Saints of the Day: Anthony the New, the ascetic of Berrea in Macedonia; New-Martyr George of Ionnina DIRECTORY WELCOME V. Rev. Fr. John Salem Parish Priest 410-9399 We welcome all our visitors. It is an honor to have you worshipping with us. You may find the worship of the Rev. Fr. Elias Khouri Ancient Church very different. We welcome your questions. Assistant Priest 640-3016 Please join us for our Reception held in the Church Hall V. Rev. Fr. Constantine Nasr immediately following the Divine Liturgy. Emeritus We understand Holy Communion to be an act of our unity in Rev. Dn. Ezra Ham faith. While we work toward the unity of all Christians, it Administrator 602-9914 regrettably does not now exist. Therefore, only baptized Rev. Fr. Ambrose Perry Orthodox Christians (who have properly prepared) are Attached permitted to participate in Holy Communion. However, everyone is welcome to partake of the blessed bread that is Anthony Ruggerio 847-721-5192 distributed at the end of the service. We look forward to Youth Director meeting you during the Reception that follows the service. Mom’s Day Out & Pre-K NEW ORTHROS & LITURGY BOOK Sara Cortez – Director 639-2679 • Orthros: p. 4 Email: [email protected] Facebook: “St Elijah Mom’s Day Out” • The Divine Liturgy p. -

Bulgakov Handbook

October 21 G.† Our Ven. Father Hilarion the Great He was born in Palestine, near Gaza City, studied the sciences and was baptized in Alexandria. When he was 15 years old, Hilarion heard about Ven. Anthony the Great and admiring "Anthony's spiritually divine, virtuous way of life" went to him. Having returned home with a blessing from Ven. Anthony, Hilarion found that his parents died and, "despising all worldly pleasures", distributed all his remaining inherited estate to the poor and in a certain deserted place was devoted entirely to prayer and abstinence. St. Hilarion struggled a lot with unclean thoughts, who confused his mind and inflamed his body; but he exhausted his body with work and drove away these thoughts by prayer and meditation on God. The holy hermit suffered much from demons and more than once while standing in prayer heard the crying of children, sobbing of women, roaring of lions and other wild animals, awful noises and confusion presented by the demons. But he did not fear the "demonic traps" and through fervent prayer conquered the "gloomy enemy powers". Once, robbers set upon the holy ascetic, but he by the power of his word convinced them to leave their vice and to lead a good life. Soon all of Palestine heard about the holy hermit's life and many began to come to him for healing of body and soul, but others wished to save their soul under his direction. With his blessing many monasteries were built in Palestine, and going from one monastery to another, he established a strict ascetic paradigm of life in them, having become the same kind of trainer for those seeking salvation in Palestine as Ven. -

Russian Orthodoxy and Women's Spirituality In

RUSSIAN ORTHODOXY AND WOMEN’S SPIRITUALITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA* Christine D. Worobec On 8 November 1885, the feast day of Archangel Michael, the Abbess Taisiia had a mystical experience in the midst of a church service dedicated to the tonsuring of sisters at Leushino. The women’s religious community of Leushino had recently been ele vated to the status of a monastery.1 Conducting an all-women’s choir on that special day, the abbess became exhilarated by the beautiful refrain of the Cherubikon hymn, “Let us lay aside all earthly cares,” and envisioned Christ surrounded by angels above the iconostasis. She later wrote, “Something was happening, but what it was I am unable to tell, although I saw and heard every thing. It was not something of this world. From the beginning of the vision, I seemed to fall into ecstatic rapture Tears were stream ing down my face. I realized that everyone was looking at me in astonishment, and even fear....”2 Five years later, a newspaper columnistwitnessedasceneinachurch in the Smolensk village of Egor'-Bunakovo in which a woman began to scream in the midst of the singing of the Cherubikon. He described “a horrible in *This book chapter is dedicated to the memory of Brenda Meehan, who pioneered the study of Russian Orthodox women religious in the modern period. 1 The Russian language does not have a separate word such as “convent” or nunnery” to distinguish women’s from men’s monastic institutions. 2 Abbess Thaisia, 194; quoted in Meehan, Holy Women o f Russia, 126. Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture. -

Mediterranean Festival—2018

1 The Messenger October 2018 Vol. 31 Issue 10 Mediterranean Festival—2018 2 Orthodox Trivia Quiz 1. Who is the 1st Christian martyr? 7. As Orthodox Christians, we believe “God is the a. Peter b. Stephen Trinity: three ________, one God.” c. David d. Mary Magdalene a. Spirits b. Persons c. Gods d. Angels 2. When did Christianity become legal in the Roman Empire? 8. Which prophet is commonly ascribed as the a. 33 AD b. 70 AD author of the Book of Psalms from the Old Testament? c. 313 AD d. 1054 AD a. David b. Solomon c. Moses d. Abraham 3. Who is referred to as the “new Adam” in some liturgical texts within the Orthodox Church? a. John the Baptist 9. Which city is NOT considered to be one of the b. Jesus Christ first five patriarchates (important centers) of c. Emperor Constantine the Great Christianity? d. Prophet Moses a. Rome b. Bethlehem c. Jerusalem d. Alexandria 4. Who is the first called of the 12 Apostles of Christ? 10. What Great Feast in the Life of the Church is a. Peter c. Matthew celebrated on November 21st (New Calendar)? c. Andrew d. Judas a. Transfiguration of our Lord b. Entrance of our Lord into the Temple 5. What was Peter’s occupation before becoming c. Nativity of the Theotokos a “follower of Christ?” d. Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple a. tent-maker b. carpenter c. farmer d. fisherman 6. Why do Orthodox Christians gather on Sundays to worship during Liturgy and celebrate the Eucharist OR what do we commemorate every Sunday throughout the year? a. -

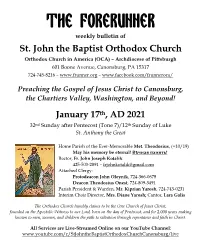

The Forerunner

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

St. Anthony the Great Orthodox Church

St. Anthony the Great Orthodox Church Metropolitan JOSEPH, Archbishop A parish of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America Bishop BASIL of Wichita Church Office Tuesday-Friday: 9:00am - 4:00pm Office is Closed on Mondays (281) 251-6000 [email protected] www.StAnthonyTheGreat.org WELCOME TO OUR VISITORS & GUESTS It is a joy to have you with us this morning! Please feel free to complete the Welcome Card or sign the Guest Book in the narthex. Thank you for worshipping with us! RECEIVING COMMUNION While the Orthodox Church continues to pray for the unity of all, Holy Communion is only served to Orthodox Christians who have prepared themselves through prayer, fasting and confession. ELECTRONIC DEVICES Upon entering the church, we ask that you silence your cell phone and refrain from using electronic devices during the service. PRAYER REQUESTS To be included on the prayer list, or to join the parish prayer chain, please contact the church office at [email protected]. TODAY’S ANNOUNCEMENTS ~ August 23, 2020 BREAD OF OBLATION is offered by Vasiliki Domati. SCHEDULE OF THIS WEEK’S DIVINE SERVICES Saturday, August 29 4:30 p Confession (or by appointment w/Fr. Anthony) 5:00 p Great Vespers Sunday, August 30 9:00 AM Orthros 10:00 AM Divine Liturgy Sunday Divine Liturgy live-streamed on our Facebook Page https://www.facebook.com/stanthonyspringtx/ UPCOMING ONLINE MEETINGS AND ACTIVITIES SEEKERS, ENQUIRERS & CATECHUMENS CLASS via ZOOM continues this Wednesday, August 26th at 6:30p. The class will discuss “Church Etiquette” and all are welcome to join! ARE YOU 55 OR OLDER? Join Fr. -

Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a Division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by Permission

WO M E N I N T H E MISSION OF THE CHURCH Their Opportunities and Obstacles throughout Christian History Leanne M. Dzubinski and Anneke H. Stasson K Leanne Dzubinski & Anneke Stasson, Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by permission. _DzubinskiStasson_WomenMissionChurch_JH_wo.indd 3 1/27/21 3:29 PM CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction: Women in Ministry Is Not a Twentieth- Century Phenomenon 1 PART 1 WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN THE EARLY CHURCH 1. Patrons, Missionaries, Apostles, Widows, and Martyrs 13 2. Virgins, Scholars, Desert Mothers, and Deacons 35 PART 2 WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND THE MIDDLE AGES 3. Mothers, Sisters, Empresses, and Queens 59 4. Medieval Nuns 83 5. Beguines and Mystics 105 PART 3 WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP SINCE THE REFORMATION 6. Women Preachers in America 125 7. Social Justice Activists 145 vii Leanne Dzubinski & Anneke Stasson, Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by permission. _DzubinskiStasson_WomenMissionChurch_JH_wo.indd 7 1/27/21 3:29 PM viii Contents 8. Denominational Missionaries and Bible Women 161 9. Faith Missionaries, Evangelists, and Church Founders 183 Conclusion: Women’s Leadership in the Church 203 Bibliography 215 Index 233 Leanne Dzubinski & Anneke Stasson, Women in the Mission of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 Used by permission. _DzubinskiStasson_WomenMissionChurch_JH_wo.indd 8 1/27/21 3:29 PM INTRODUCTION Women in Ministry Is Not a Twentieth- Century Phenomenon (Anneke) am sitting in a guesthouse at a monastery in Michigan. -

Saint Anthony Orthodox Church

SAINT ANTHONY ORTHODOX CHURCH Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese www.orthodoxbutler.org ADDRESS: 400 S. Sixth Avenue, Butler, PA 16001 RECTOR: Rev. Bogdan Gabriel Bucur CONTACT: 724.287.6983 (church); 412.390.8208 (priest); [email protected] FOURTEENTH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST 6 September 2015 TONE 5—Commemoration of the Miracle of the Archangel Michael at Colossæ. Martyrs Eudoxius, Zeno, and Macarius (311-312). St. Archippus of Herapolis. Martyr Romulus (107-115). Hieromartyr Cyril, Bishop of Gortyna (3rd-4th c.). Martyrs Cyriacus, Faustus the Presbyter, Abibas the Deacon, and 11 others, at Alexandria (ca. 250). St. David of Hermopolis in Egypt (4th c.). Hieromartyr Maksym Sandowicz of Carpatho-Rus’ (1914). FIRST ANTIPHON It is good to give praise unto the Lord, and to chant unto Thy Name, O Most High! Refrain: Through the intercessions of the Theotokos, O Savior, save us! To proclaim in the morning Thy mercy, and Thy truth by night! (R.:) Upright is the Lord our God and there is no unrighteousness in Him (R.:) Glory… Now and ever… (R.:) SECOND ANTIPHON The Lord is King, He is clothed with majesty; the Lord is clothed with strength and hath girt Himself! (R.:) O Son of God, Who art risen from the dead: save us who sing to Thee, “Alleluia”! For He established the world which shall not be shaken! (R.:) Holiness befits Thy house, O Lord, unto length of days! (R.:) Glory… Now and ever… (Only begotten Son and Word of God …) LITTLE ENTRANCE Come, let us worship and fall down before Christ! O Son of God, Who art risen from the dead, save us who sing to Thee: “Alleluia”! TROPARION OF THE RESURRECTION (Tone 5): Let us believers praise and worship the Word; coeternal with the Father and the Spirit, born of the Virgin for our salvation. -

Immoveable Feasts

Immoveable Feasts There are numerous feasts which always fall on the same day of the month every year. These are called the immoveable feasts. For example, the Nativity of our Lord (Christmas) always falls on December 25, and the Dormition of the Mother of God always falls on August 15. The cycle of immoveable feasts begins on September 1, the beginning of the Church Year, and ends on August 31. While the centre of the moveable feasts is Pascha (Easter), the centre of the immoveable feasts is the Nativity of our Lord (Christmas). Sometimes, the cycle of immoveable feasts is called the Christmas Cycle. Below is a listing of the more important feast days through the Church Year. For a complete listing for every day of the year, please refer to the Church Calendar. September 1 Beginning of the Indiction, that is, the New Year; Commemoration of Our Holy Father Symeon the Stylite (459) and His Mother Martha; and the Synaxis of the Most Holy Mother of God of Miasenes 8 The Nativity of Our Most Holy Lady, the Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary 13 Commemoration of the Dedication of the Holy Church of the Resurrection of Christ Our God (335); the Forefeast of the Exaltation of the Precious and Life-Giving Cross; the Holy Priest-Martyr Cornelius the Centurion 14 The Universal Exaltation of the Precious and Life-Giving Cross 23 The Conception of the Honorable and Glorious Prophet, Forerunner and Baptist John 26 The Passing of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian 28 Our Venerable Father and Confessor Chariton (Pronounced “Káriton”) -

Bulletin January 19

Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church 950 North Grace Street, Lombard, IL 60148 Tel: 630-932-9640 / Fax: 630-932-9463 www.ollchicago.org Church Clergy Father Pierre ElKhoury, M.L.M., Pastor Deacon John Sfire Subdeacon Thomas Podraza Subdeacon George Romanos Mass Schedule Sundays : 9:30 am (English) & 11:30 am (English & Arabic) Confession Contact the priest or the church office to arrange your confession during the week. Baptism Please call the Church office for arrangements one month prior to the celebration of the Sacrament. Marriage Please allow at least six months of preparation time. Date arrangements are made after the initial meet with pastor before any other commitments are made. Ministry of the Sick If any parishioner is seriously ill at home or in a hospital, please call the pastor or the Church office to arrange for Communion, Confession or Anointing of the Sick. Maronite Catholic Education Catechism Classes for children are on Sundays from 10:20 am – 11:20 am. Page 1 of 8 Glorious Epiphany Feast of Saint Anthony, The Great JANUARY 19, 2019 Sayings by Saint Anthony the Great A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him, saying, "You are mad; you are not like us." Anthony said, ‘I saw evil spreads out over the world, and I said, “What can help us against such thing?” Then I heard a voice saying to me, “Humility.” A brother said to St Anthony, “Pray for me.” And he replied, “My prayer will bring you no mercy from God, if you yourself do not make the effort to pray.” “If a man loves God with all his heart, he will gain the fear of God; and the fear of God will produce tears, and tears will produce strength; then the soul will bear all kinds of fruits.” Page 2 of 8 We pray for all the sick in our Parish “Heal me, O Lord, and I will be healed; save me and I will be saved, for you are the one I praise” Jeremiah 17:14 Mass Intentions for NEXT SUNDAY JANUARY 26, 2019 09:30 AM Abdo Daou and Jeanette Mattar (Dr. -

Jan 17Th, 2021

Holy Trinity Orthodox Church Sun, January 17, 2021 - T he Young Rich Ruler 32ND SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST — Tone 7. Venerable and Godbearing Father Anthony the Great (356). Epistle Reading - Colossians 1:12-18 giving thanks to the Father who has qualified us to be partakers of the inheritance of the saints in the light. He has delivered us from the power of darkness and conveyed us into the kingdom of the Son of His love, in whom we have redemption through His blood, the forgiveness of sins. He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. For by Him all things were created that are in heaven and that are on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or powers. All things were created through Him and for Him. And He is before all things, and in Him all things consist. And He is the head of the body, the church, who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, that in all things He may have the preeminence. Hymns for Today Gospel Reading - Luke 18:18-27 By Thy Cross Thou didst destroy death. To the thief Thou Now a certain ruler asked Him, saying, “Good Teacher, didst open Paradise. For the Myrrhbearers Thou didst what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” So Jesus said to change weeping into joy, and Thou didst command Thy him, “Why do you call Me good? No one is good but One, disciples, O Christ God, to proclaim that Thou art risen, that is, God.