The Black River Lower Morass: a Threatened Wetland in Jamaica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black River Pilot Project

Final Project report for the ‘Mitigating the Threat of Invasive Alien Species (IAS) in the Insular Caribbean project: Black River IAS Pilot Project’ Prepared and submitted by Dr Kurt McLaren (Principal investigator [PI]/Project manager) 1 1. Introduction The Black River morass is the largest freshwater wetland ecosystem in Jamaica and the second largest in the Caribbean. It is a biologically diverse and extremely complex natural wetland ecosystem that supports a large number of plants, animals and natural communities. The Morass support high levels of endemic species which are severely threatened by anthropogenic disturbance owing to their relatively small size and accessibility to human encroachment. In recognition of its value as a reservoir of endemic biodiversity, and its contribution to the livelihoods of local communities, the Black River morass will be designated as a protected area in 2015. It was also designated as a Ramsar site in 1997, signifying that it is a wetland ecosystem of international importance. The Ramsar designation should provide both the impetus for national action and the framework for international cooperation geared towards the conservation and sustainable use of this important wetland. To date however, the threats to the Black River morass remain unchecked (selective removal of trees, burning, the cultivation of marijuana and habitat encroachment), resulting in the continued loss or degradation of various habitat types. Conservation of the swamp forest is challenged by on-going human impacts (e.g., tree cutting, fires) and is compounded by the establishment of two exotic plant species that are at different stages of invasion. Although it may be possible to eradicate the more recently introduced invasive, Melaleuca quinquenervia, the other invasive, Alpinia allughas, is now firmly established. -

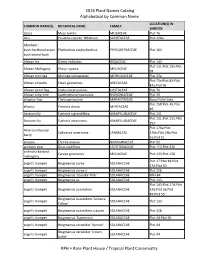

2016 Plant Names Catalog Alphabetical by Common Name

2016 Plant Names Catalog Alphabetical by Common Name LOCATION(S) IN COMMON NAME(S) BOTANICAL NAME FAMILY GARDEN abaca Musa textilis MUSACEAE Plot 76 abiu Pouteria caimito 'Whitman' SAPOTACEAE Plot 128a Abraham- bush:hardhead:scipio- Phyllanthus epiphyllanthus PHYLLANTHACEAE Plot 164 bush:sword-bush African iris Dietes iridioides IRIDACEAE Plot 143 Plot 131:Plot 19a:Plot African Mahogany Khaya nyasica MELIACEAE 58 African moringa Moringa stenopetala MORINGACEAE Plot 32a Plot 71a:Plot 83:Plot African oil palm Elaeis guineensis ARECACEAE 84a:Plot 96 African spiral flag Costus lucanusianus COSTACEAE Plot 76 African tulip-tree Spathodea campanulata BIGNONIACEAE Plot 29 alligator flag Thalia geniculata MARANTACEAE Royal Palm Lake Plot 158:Plot 45:Plot allspice Pimenta dioica MYRTACEAE 46 Amazon lily Eucharis x grandiflora AMARYLLIDACEAE Plot 131 Plot 131:Plot 151:Plot Amazon-lily Eucharis amazonica AMARYLLIDACEAE 152 Plot 176a:Plot American beauty Callicarpa americana LAMIACEAE 176b:Plot 19b:Plot berry 3a:Plot 51 anaqua Ehretia anacua BORAGINACEAE Plot 52 anchovy pear Grias cauliflora LECYTHIDACEAE Plot 112:Plot 32b andiroba:bastard Carapa guianensis MELIACEAE Plot 133:Plot 158 mahogany Plot 17:Plot 18:Plot angel's trumpet Brugmansia aurea SOLANACEAE 27d:Plot 50 angel's trumpet Brugmansia aurea x SOLANACEAE Plot 32b angel's trumpet Brugmansia 'Ecuador Pink' SOLANACEAE RPH-B4 angel's trumpet Brugmansia sp. SOLANACEAE Plot 133 Plot 143:Plot 27d:Plot angel's trumpet Brugmansia suaveolens SOLANACEAE 32b:Plot 3a:Plot 49:Plot 50 Brugmansia suaveolens -

Hort Pro Version V List For

HORTICOPIA® Professional Woody Plus Refresh Library Plant List Name Name Abelia 'Mardi Gras' Acalypha wilkesiana 'Petticoat' Abelia x grandiflora 'John Creech' Acer buergerianum 'Goshiki kaede' Abelia x grandiflora 'Sunshine Daydream' Acer campestre 'Carnival' Abelia schumannii 'Bumblebee' Acer campestre 'Evelyn (Queen Elizabeth™)' Abies concolor 'Compacta' Acer campestre 'Postelense' Abies concolor 'Violacea' Acer campestre 'Tauricum' Abies holophylla Acer campestre var. austriacum Abies koreana 'Compact Dwarf' Acer cissifolium ssp. henryi Abies koreana 'Prostrate Beauty' Acer davidii ssp. grosseri Abies koreana 'Silberlocke' Acer elegantulum Abies nordmanniana 'Lowry' Acer x freemanii 'Armstrong II' Abies nordmanniana 'Tortifolia' Acer x freemanii 'Celzam' Abies pindrow Acer x freemanii 'Landsburg (Firedance®)' Abies pinsapo 'Glauca' Acer x freemanii 'Marmo' Abies sachalinensis Acer x freemanii 'Morgan' Abutilon pictum 'Aureo-maculatum' Acer x freemanii 'Scarlet Sentenial™' Acacia albida Acer heldreichii Acacia cavenia Acer hyrcanum Acacia coriacea Acer mandschuricum Acacia erioloba Acer maximowiczianum Acacia estrophiolata Acer miyabei 'Morton (State Street®)' Acacia floribunda Acer mono Acacia galpinii Acer mono f. dissectum Acacia gerrardii Acer mono ssp. okamotoanum Acacia graffiana Acer monspessulanum Acacia karroo Acer monspessulanum var. ibericum Acacia nigricans Acer negundo 'Aureo-marginata' Acacia nilotica Acer negundo 'Sensation' Acacia peuce Acer negundo 'Variegatum' Acacia polyacantha Acer oliverianum Acacia pubescens Acer -

National Ballast Water Status Assessment and Economic Assessment JAMAICA

UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES MONA CAMPUS CENTRE FOR MARINE SCIENCES National Ballast Water Status Assessment and Economic Assessment JAMAICA October, 2016 This Technical Report was prepared by the Centre for Marine Sciences, University of the West Indies, Mona for the Maritime Authority of Jamaica and the GEF-UNDP-IMO GloBallast Partnerships Programme The main author was Dr Dayne Buddo, with significant inputs from Miss Denise Chin, Miss Achsah Mitchell and Mr Stephan Moonsammy Reviewed by Mr Vassilis Tsigourakos (RAC/REMPEITC) and Mr Antoine Blonce (GloBallast) 1 Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ..........................................................................................................................3 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1.0: SHIPPING ..............................................................................................................6 1.1 THE ROLE OF SHIPPING ON THE NATIONAL ECONOMY ..............................................6 1.2 PORTS AND HARBOURS .................................................................................................... 13 1.2.1 THE PORT OF KINGSTON ............................................................................................................. 13 1.2.2 PORT RHOADES ........................................................................................................................... 18 1.2.3 MONTEGO BAY .......................................................................................................................... -

1 Palm Tree Susceptibility to Hemi-Epiphytic Parasitism By

PALM TREE SUSCEPTIBILITY TO HEMI-EPIPHYTIC PARASITISM BY FICUS BY GREGORY KRAMER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Gregory Kramer 2 To my parents for always supporting my curiosity for the sciences and allowing me to follow that curiosity through education 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to sincerely thank my entire supervisory committee, Dr. Kimberly Moore, Dr. George E. Fitzpatrick, and Dr. Wagner Vendrame for making my learning experience at UF an exceptional one. A special acknowledgment to Dr. Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my degree, and, and for being a constant source of guidance throughout my studies. I would also like to thank the staff of Montgomery Botanical Center for allowing me to use the facility to conduct my research, in particular, Dr. Patrick Griffith, Executive Director; Arantza A. Strader, Database Supervisor; and Vickie Murphy, Nursery Curator. And finally to my entire family, who have supported my curiosity for the sciences from a young age, in particular, Dave, Nancy and Emil. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ 6 LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................... -

Raphides in Palm Embryos and Their Systematic Distribution

Annals of Botany 93: 415±421, 2004 doi:10.1093/aob/mch060, available online at www.aob.oupjournals.org Raphides in Palm Embryos and their Systematic Distribution SCOTT ZONA* Fairchild Tropical Garden, 11935 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables (Miami), FL 33156-4242, USA Received: 25 July 2003 Returned for revision: 25 November 2003 Accepted: 18 December 2003 Published electronically: 23 February 2004 d Background and Aims Raphides are ubiquitous in the palms (Arecaceae), where they are found in roots, stems, leaves, ¯owers and fruits. Their occasional presence in embryos, ®rst noticed over 100 years ago, has gone lar- gely unexamined. d Methods Embryos from 148 taxa of palms, the largest survey of palm embryos to date, were examined using light microscopy of squashed preparations under non-polarized and crossed polarized light. d Key Results Raphides were found in embryos of species from the three subfamilies Coryphoideae, Ceroxyloideae and Arecoideae. Raphides were not observed in the embryos of species of Calamoideae or Phytelephantoideae. The remaining subfamily, the monospeci®c Nypoideae, was not available for study. d Conclusions Within the Coryphoideae and Ceroxyloideae, embryos with raphides were rare, but within the Arecoideae, they were a common feature of the tribes Areceae and Caryoteae. ã 2004 Annals of Botany Company Key words: Anatomy, Arecaceae, calcium oxalate, embryology, embryos, Palmae, raphides. INTRODUCTION lineages within the palm family. The purpose of this survey Raphides, bundles of needle-shaped crystals of calcium was to determine if raphides are con®ned to certain lineages and if they could be used as additional evidence of oxalate monohydrate in specialized cells, are found phylogenetic relationships. -

Germination of Palm Seed

134 PRINCIPES [Vo]. l5 Germination of Palm Seed JAcr< I(osnpnNx Key West, Florid.a One question often asked of me is: Astrocaryum aculeatum r044 "How long does it take a palm seed to A.up' 65 germinate?" This is one question I do A. Standleyanum (l) 68,47 & 96 not know how to answer. Is there an A. uulgare (I') 4I3 & 334 answer? Can you answer it? Bactris Gasipaes 69 For several years I have kept careful B. major lBB germination records. I now submit them B. rhaphidacantha 197 to The Palm Society in hopes that they B. sp. (Nloore# 9529') 150 may help someone,someday, to find the Bentinckianicobarica (I) 85,82&74 answer. Here are my data: Borassussp. (f) 283"265 & 273 Brassiophoenix d,rymophloeoiiles 245 Butia capitata t49 No. of Name of palm* days B. capitata var. capitata 161 B. eriospatha (.I') 673 & 230 (2) Acrocomia mexicana 440 Calamussp. (1) 107 & 408 A. scleracarpa(3) oro Calyptr ocalyx spicatus I9 Actinorhytis Calapparia 7l Carpentaria acuminttta 78 Aiphanesacanthophylla (1) 9I,43 & 95 Caryota Cumingii (I) 142& 114 A. caryotaelolia(I) 7I, 60 & 61 C. mitis r49 A. erosa (I) 58& rr0 C, urens 198 carrupestre(I) 62 & 62 Allagoptera Chamaerlor ea cataract(rrunl 82 ArchontophoenixCunninghamiana 90 C. costa"ricana 4T 53 a. "p. C. elatior II8 Aliciae 4I Areca C. erumpens(l) 235 & r94 A. (I) 55,25 & 30 Catechu C. glaucilolia 244 (I) 42&6I A. concinna C. rnetallica 197 A. Langloisiana 114 C. microspadix (.I) 105,98 & 65 A. 3I "p. C. monostachys 148 A. -

Ancient Polyploidy and Genome Evolution in Palms

Faculty & Staff Scholarship 2019 Ancient Polyploidy and Genome Evolution in Palms Craig F. Barrett Michael R. McKain Brandon T. Sinn Xue Jun Ge Yuqu Zhang See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Biology Commons Authors Craig F. Barrett, Michael R. McKain, Brandon T. Sinn, Xue Jun Ge, Yuqu Zhang, Alexandre Antonelli, and Christine D. Bacon GBE Ancient Polyploidy and Genome Evolution in Palms Craig F. Barrett1,*, Michael R. McKain2, Brandon T. Sinn1, Xue-Jun Ge3, Yuqu Zhang3, Alexandre Antonelli4,5,6, and Christine D. Bacon4,5 1Department of Biology, West Virginia University 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama 3Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, PR China Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/gbe/article-abstract/11/5/1501/5481000 by guest on 05 May 2020 4Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Sweden 5Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre, Go¨ teborg, Sweden 6Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted: April 19, 2019 Data deposition: This project has been deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the accession BioProject (PRJNA313089). Abstract Mechanisms of genome evolution are fundamental to our understanding of adaptation and the generation and maintenance of biodiversity, yet genome dynamics are still poorly characterized in many clades. Strong correlations between variation in genomic attributes and species diversity across the plant tree of life suggest that polyploidy or other mechanisms of genome size change confer selective advantages due to the introduction of genomic novelty. -

Towards a Phylogenetic Nomenclature of Tracheophyta

TAXON 56 (3) • August 2007: E–E44 Cantino & al. • Phylogenetic nomenclature of Tracheophyta PHYLOGENEtic noMEncLAturE Towards a phylogenetic nomenclature of Tracheophyta Philip D. Cantino2, James A. Doyle1,3, Sean W. Graham1,4, Walter S. Judd1,5, Richard G. Olmstead1,6, Douglas E. Soltis1,5, Pamela S. Soltis1,7 & Michael J. Donoghue8 Authors are listed alphabetically, except for the first and last authors. 2 Department of Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence) 3 Section of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, U.S.A. 4 UBC Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research, 6804 SW Marine Drive, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z4 5 Department of Botany, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-8526, U.S.A. 6 Department of Biology, P.O. Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195-5325, U.S.A. 7 Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, U.S.A. 8 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208106, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8106, U.S.A. Phylogenetic definitions are provided for the names of 53 clades of vascular plants. Emphasis has been placed on well-supported clades that are widely known to non-specialists and/or have a deep origin within Tracheophyta or Angiospermae. These treatments follow the draft PhyloCode and illustrate the applica- tion of phylogenetic nomenclature in a variety of nomenclatural and phylogenetic contexts. Phylogenetic nomenclature promotes precision in distinguishing crown, apomorphy-based, and total clades, thereby improving communication about character evolution and divergence times. -

Graham, S. W., J. M. Zgurski, M. A

Allen Press x DTPro System GALLEY 3 File # 01ee Name /alis/22_101 12/16/2005 01:24PM Plate # 0-Composite pg 3 # 1 Aliso, 22(1), pp. 3±20 q 2006, by The Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA 91711-3157 ROBUST INFERENCE OF MONOCOT DEEP PHYLOGENY USING AN EXPANDED MULTIGENE PLASTID DATA SET SEAN W. G RAHAM,1,6 JESSIE M. ZGURSKI,2 MARC A. MCPHERSON,2,7 DONNA M. CHERNIAWSKY,2,8 JEFFERY M. SAARELA,1 ELVIRA S. C. HORNE,2 SELENA Y. S MITH,2 WINSON A. WONG,2 HEATH E. O'BRIEN,2,9 VINCENT L. BIRON,2,10 J. CHRIS PIRES,3 RICHARD G. OLMSTEAD,4 MARK W. C HASE,5 AND HARDEEP S. RAI1 1UBC Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research, University of British Columbia, 6804 SW Marine Drive, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada; 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E9, Canada; 3Department of Agronomy, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA; 4Department of Biology, Box 351800, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA; 5Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, UK 6Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT We use multiple photosynthetic, chlororespiratory, and plastid translation apparatus loci and their associated noncoding regions (ca. 16 kb per taxon, prior to alignment) to make strongly supported inferences of the deep internal branches of monocot phylogeny. Most monocot relationships are robust (an average of ca. 91% bootstrap support per branch examined), including those poorly supported or unresolved in other studies. Our data strongly support a sister-group relationship between Asparagales and the commelinid monocots, the inclusion of the orchids in Asparagales, and the status of Petro- saviaceae as the sister group of all monocots except Acorus and Alismatales. -

Ancient Polyploidy and Genome Evolution in Palms

GBE Ancient Polyploidy and Genome Evolution in Palms Craig F. Barrett1,*, Michael R. McKain2, Brandon T. Sinn1, Xue-Jun Ge3, Yuqu Zhang3, Alexandre Antonelli4,5,6, and Christine D. Bacon4,5 1Department of Biology, West Virginia University 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama 3Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, PR China 4Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Sweden 5Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre, Go¨ teborg, Sweden 6Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted: April 19, 2019 Data deposition: This project has been deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the accession BioProject (PRJNA313089). Abstract Mechanisms of genome evolution are fundamental to our understanding of adaptation and the generation and maintenance of biodiversity, yet genome dynamics are still poorly characterized in many clades. Strong correlations between variation in genomic attributes and species diversity across the plant tree of life suggest that polyploidy or other mechanisms of genome size change confer selective advantages due to the introduction of genomic novelty. Palms (order Arecales, family Arecaceae) are diverse, widespread, and dominant in tropical ecosystems, yet little is known about genome evolution in this ecologically and economically important clade. Here, we take a phylogenetic comparative approach to investigate palm genome dynamics using genomic and transcriptomic data in combination with a recent, densely sampled, phylogenetic tree. We find conclusive evidence of a paleopolyploid event shared by the ancestor of palms but not with the sister clade, Dasypogonales. We find evidence of incremental chromosome number change in the palms as opposed to one of recurrent polyploidy. -

Introducing Aquatic Palms

International Waterlily and Water Gardening Society Spring, 2005 Volume 20, Number 1 Page 2 The Water Garden Journal Vol. 20, No. 1 In This Issue President’s Comments Page 2 President’s Comments by Wayne Davis by Wayne Davis, Jr. Page 3 Executive Director’s Comments It is hard to believe that Spring is only two weeks away, given the fact that the temperature outside today is in the by Paula Biles teens. Having just returned from a swing through Texas Page 3 IWGS Committee Chairs where the temperature was 50 degrees higher and lilies are in bloom we are very anxious for warm weather here. Page 4 The Grower’s Corner Visiting with Ken Landon in San Angelo we were by John Loggins hopeful that we would get to see the new ponds being Page 5 Aquatic Palms built there for one of our IWGS Certified Collections. Unfortunately, due to weather delays the ponds were not by Jorge Monteverde yet completed. Ken hopes to have them operational by Page 12 The 10% Solution the middle of April. What we were able to see looks by Dick Schuck extremely exciting and should be quite spectacular. If you are anywhere close to San Angelo this season it Page 13 Affiliate Societies would be well worth your time to visit this facility. by Tom Frost Hopefully, if you have not already done so, you are Page 14 Water Gardens on Tour planning to contribute to our Memorial Fund which will by Suzan Phillips be used to recognize eminent individuals from within our Page 14 Extreme Pond Plants industry who have passed on.