Musical Traditions KS4 Music - Television Teacher's Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kevin Burke and Cal Scott

WWhhaatt TThheeyy’’rree SSaayyiinngg aabboouutt KKeevviinn BBuurrkkee THE NEW YORK TIMES THE WASHINGTON POST A Big Wide World KEVIN BURKE & CAL SCOTT of Music "Across the Black River" Loftus Friday, May 11, 2007; Page WE09 By JON PARELES Published: June 29, KEVIN BURKE IS ONE of the greatest Irish 2007 fiddlers of the past half-century, but he has lived in Jack Vartoogian/ FrontRowPhotos Ireland for only five of his 57 years. He was raised in London by parents from County Sligo, and he has What follows is a lived in Portland, Ore., since 1979. He is thus a selection of some of the perfect exemplar for the far-flung Irish diaspora and most notable world weaves the multinational strands of today's "Irish" music CDs released over music into his impressive new album, "Across the the last year. Black River," a collaboration with Portland film composer Cal Scott. KEVIN BURKE AND CAL SCOTT "Across the Black River" (Loftus) Scott composed three of the instrumental album's tunes, including the spellbinding "The Lighthouse Born in England to Irish parents and now living in Keeper's Waltz," and plays graceful guitar, mandolin Portland, Ore., Kevin Burke is one of the great and bouzouki throughout. But the dominant voice is living Celtic fiddlers. His first album on his own that of Burke's violin, which never wavers in pitch or label is a collaboration with the self-effacing guitarist timbre but sings out with a confidence that allows the Cal Scott and various guests that's cozy and mature, listener to relax. -

Irish Music If You Are a Student, Faculty Member Or Graduate of Wake and Would Like to Play Irish Music This May Be for You

Irish Music If you are a student, faculty member or graduate of Wake and would like to play Irish music this may be for you. Do you know the difference between a slip jig and a slide? What was the historic connection between Captain O’Neill of Chicago and Irish music? Who was Patsy Touhey and was he American or Irish? What are Uilleann pipes? What is sean-nós singing and is there a connection with Irish poetry? For the answers, join this Irish Music association. GOALS: to have a load of fun playing Irish music and in the process: Create a forum for a dynamic musical interaction recognizing and promoting Irish music Provide an opportunity for musicians to study, learn, and play together in the vibrant Irish folk tradition Promote co-operation between outside music/fine arts departments in Winston-Salem Enhance a community awareness of Irish music, song and culture Expose interested music, and other fine arts, students to an international dimension of folk music based on the Irish tradition as a model Explore the vocal and song traditions in Ireland in the English and Gaelic languages Learn about the history of Irish folk music in America HOW THIS WILL BE DONE: Meet every two weeks and play with a Gaelic-speaking piper and whistler from Ireland, define goals, share pieces, develop a repertoire; organize educational and academic demonstrations/projects; hear historic shellac, vinyl and cylinder recordings of famous pipers, fiddlers, and singers. Play more music. WHAT THIS IS: Irish, pure 100%..... to learn not only common dance music forms including double jigs, reels, hornpipes, polkas but also less common tune forms such as sets, mazurkas, song airs and lullabies etc WHAT THIS IS NOT: Respecting our Celtic brethren, this is NOT Celtic, Scottish, Welsh, Breton, Galician or Canadian/Cape Breton music which is already very well represented by some fine players here in North Carolina. -

Traditional Irish Music Presentation

Traditional Irish Music Topics Covered: 1. Traditional Irish Music Instruments 2 Traditional Irish tunes 3. Music notation & Theory Related to Traditional Irish Music Trad Irish Instruments ● Fiddle ● Bodhrán ● Irish Flute ● Button Accordian ● Tin/Penny Whistle ● Guitar ● Uilleann Pipes ● Mandolin ● Harp ● Bouzouki Fiddle ● A fiddle is the same as a violin. For Irish music, it is tuned the same, low to high string: G, D, A, E. ● The medieval fiddle originated in Europe in ● The term “fiddle” is used the 10th century, which when referring to was relatively square traditional or folk music. shaped and held in the ● The fiddle is one of the arms. primarily used instruments for traditional Irish music and has been used for over 200 years in Ireland. Fiddle (cont.) ● The violin in its current form was first created in the early 16th century (early 1500s) in Northern Italy. ● When fiddlers play traditional Irish music, they ornament the music with slides, cuts (upper grace note), taps (lower grace note), rolls, drones (also known as a double stop), accents, staccato and sometimes trills. ● Irish fiddlers tend to make little use of vibrato, except for slow airs and waltzes, which is also used sparingly. Irish Flute ● Flutes have been played in Ireland for over a thousand years. ● There are two types of flutes: Irish flute and classical flute. ● Irish flute is typically used ● This flute originated when playing Irish music. in England by flautist ● Irish flutes are made of wood Charles Nicholson and have a conical bore, for concert players, giving it an airy tone that is but was adapted by softer than classical flute and Irish flautists as tin whistle. -

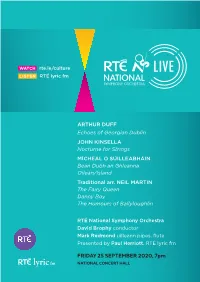

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1996

TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES: It is my pleasure to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year 1996. One measure of a great nation is the vitality of its culture, the dedication of its people to nurturing a climate where creativity can flourish. By support ing our museums and theaters, our dance companies and symphony orches tras, our writers and our artists, the National Endowment for the Arts provides such a climate. Look through this report and you will find many reasons to be proud of our Nation’s cultural life at the end of the 20th century and what it portends for Americans and the world in the years ahead. Despite cutbacks in its budget, the Endowment was able to fund thou sands of projects all across America -- a museum in Sitka, Alaska, a dance company in Miami, Florida, a production of Eugene O’Neill in New York City, a Whisder exhibition in Chicago, and artists in the schools in all 50 states. Millions of Americans were able to see plays, hear concerts, and participate in the arts in their hometowns, thanks to the work of this small agency. As we set priorities for the coming years, let’s not forget the vita! role of the National Endowment for the Arts must continue to play in our national life. The Endowment shows the world that we take pride in American culture here and abroad. It is a beacon, not only of creativity, but of free dom. And let us keep that lamp brightly burning now and for all time. -

Cs June 2010.Pdf

ISSN 1352-3848 June 2010 VOLUME 27 NO 1 THE JOURNAL OF THE LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS’ SOCIETY Jock Agnew and Martin Lowe launch ‘The Wind in the Bellows’ IN THIS ISSUE From the Archive(4): New Tune Book(5): Music Resources(6): John Armstrong’s Sword(7): Tutor Launch(9): Melrose(11): LBPS Annual Competition(13): Stock Imagery(18): Piper Gould(24): Revival or Survival?(26): Event Reports(35): Nate Banton Interview(41): Coming Events(48): Reviews(51): Back Lill(55) 1 President Julian Goodacre Minute Sec. Jeannie Campbell Chairman: Jim Buchanan Newsletter Helen Ross Treasurer Iain Wells Membership Pete Stewart Secretary Judy Barker Editor CS Pete Stewart THE JOURNAL OF THE LOWLAND AND BORDER PIPERS’ SOCIETY EDITORIAL ol 25 no 1 is the 47th issue of some from far-flung parts of the world; Common Stock [issues were there were lowland pipers in America, in V rather erratic in the early years], Australia, in Germany and the Nether- but it is the first I have supervised as lands, in India and in Oman, it seemed, editor. It is extraordinary to find that I and they were all keen to become part of am only the third person to hold this this new organization and share their privileged position. It is indeed a privi- enthusiasm. lege to take over a publication which has And because they did, I am now given recorded the trajectory of bellows piping the honour of editing the journal they from the days nearly thirty years ago first produced in Dec 1983. when various enthusiasts around the This revisiting of the early days has world began to discover that they were been largely the result of the work that not alone in their interest and that there has been done recently on preparing the was demand for an organization which Society’s records for deposit in the Na- would represent it. -

2016-Program-Booklet-Final.Pdf

CONTENTS Page Background on the Workshop 4 “Antique (SSP) Archæology” - Ralph R. Loomis Tips for a New Scottish Smallpipe Owner 8 Chris Pinchbeck The William Davidson (Glenesk) Pipes 12 Ian Kinnear Meet Your Maker - Kim Bull 15 Richard Shuttleworth Goodacre’s Razor A CUT BELOW THE OTHERS. 17 Julian Goodacre How dos Wood choice afect the Tone of Bagpipes? 18 And a number of refections on Pipe Making and Tone - Nate Banton A New Perspective on Old Technique, Scales and Embellishments 21 Barry Shears Biographies 21 Dan Foster 22 Barry Shears 21 Laura MacKenzie 23 Brian McNamara 22 Chris Gray 23 Benedict Kœhler 22 Owen Marshall 23 Bill Wakefeld 22 Iain MacInnes 23 Will Woodson Music 24 The Wisdom House Gathering (music) - Bob Cameron 25 The Lichtfeld Hills (music) - Bob Cameron 26 Didn’t We Meet in Lichtfeld? (music) - Bob Cameron Dear Piping Friends, Welcome to the 2016 Pipers’ Gathering. We’re thrilled to offer you a stellar line- up of instructors - we work hard to bring you a consistently interesting mix of folks from North American and across the pond. You’ll hear a lot at this year’s Gathering about sustainability, applied in many different ways. Attending events like ours and playing in your communities sustains a small piping tradition: • We welcome attendees of all ages who are new to bellows-blown piping. Hopefully this event will inspire you to stick with them, and do your part to sustain the traditional music community in your area in your own unique way! • We welcome those who are taking a risk and trying something new at any age! Whether you already play one type of “alt” pipes, and are giving another type a try, or are push- ing yourself a little outside your comfort zone with new tunes and techniques, you are sustaining the tradition as well. -

Jordi Savall and Carlos Núñez and Friends Thursday, May 10, 2018 at 8:00Pm This Is the 834Thconcert in Koerner Hall

Jordi Savall and Carlos Núñez and Friends Thursday, May 10, 2018 at 8:00pm This is the 834thconcert in Koerner Hall Carlos Núñez, Galician bagpipes, pastoral pipes (Baroque ancestor of the Irish Uilleann pipes) & whistles Pancho Álvarez, Viola Caipira (Brazilian guitar of Baroque origin) Xurxo Núñez, percussions, tambourins & Galician pandeiros Andrew Lawrence-King, Irish harp & psalterium Frank McGuire, bodhran Jordi Savall, treble viol (by Nicholas Chapuis, Paris c. 1750) lyra-viol (bass viol by Pelegrino Zanetti, Venice 1553) & direction PROGRAM – CELTIC UNIVERSE Introduction: Air for the Bagpipes The Caledonia Set Traditional Irish: Archibald MacDonald of Keppoch Traditional Irish: The Musical Priest / Scotch Mary Captain Simon Fraser (1816 Collection): Caledonia's Wail for Niel Gow Traditional Irish: Sackow's Jig Celtic Universe in Galicia Alalá En Querer Maruxiña Diferencias sobre la Gayta The Lord Moira Set Dan R. MacDonald: Abergeldie Castle Strathspey Traditional Scottish: Regents Rant - Lord Moira Ryan’s Mammoth Collection (Boston, 1883): Lord Moira's Hornpipe Flowers of Edinburg Charlie Hunter: The Hills of Lorne Reel: The Flowers of Edinburg Niel Gow: Lament for the Death of his Second Wife Fisher’s Hornpipe Tomas Anderson: Peter’s Peerie Boat INTERMISSION The Donegal Set Traditional Irish: The Tuttle’s Reel Traditional Scottish: Lady Mary Hay’s Scots Measure Turlough O’Carolan: Carolan’s Farewell Donegal tradition: Gusty’s Frolics Jimmy Holme’s Favorite Carolan’s Harp Anonymous Irish: Try if it is in Tune: Feeghan Geleash -

Planet Earth R Eco.R Din Gs

$4.95 (U.S.), $5.95 (CAN.), £3.95 (U.K.) IN THE NEWS ******** 3 -DIGIT 908 1B)WCCVR 0685 000 New Gallup Charts Tap 1GEE4EM740M09907411 002 BI MAR 2396 1 03 MON1 Y GREENLY U.K. Indie Dealers ELM AVE APT A 3740 PAGE LONG BEACH, CA 90807 -3402 8 Gangsta Lyric Ratings Discussed At Senate Hearing On Rap PAGE 10 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT MARCH 5, 1994 ADVERTISEMENTS MVG's Clawfinger Grammy Nominations Spur Publicity Blitz Digs Into Europe Labels Get Aggressive With Pre Award Ads BY THOM DUFFY BY DEBORAH RUSSELL Clapton, and k.d. lang experienced draw some visibility to your artists." major sales surges following Gram- A &M launched a major television STOCKHOLM -The musical LOS ANGELES -As the impact of my wins, but labels aren't waiting for advertising campaign in late Febru- rage of Clawfinger, a rock-rap the Grammys on record sales has be- the trophies anymore. Several compa- ary to promote Sting's "Ten Sum- band hailing from Sweden, has come more evident nies have kicked off aggressive ad- moner's Tales," (Continued on page 88) in recent years, vertising and promotional campaigns which first ap- nominations, as touting their nominees for the March peared on The Bill- well as victories, 1 awards. board 200 nearly a have become valu- Says A &M senior VP of sales and year ago. Sting is able marketing distribution Richie Gallo, "It would the top- nominated evil oplriin tools for record seem that people are being more ag- artist in the 36th companies. -

Davy Spillane Pipedreams Mp3, Flac, Wma

Davy Spillane Pipedreams mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Pipedreams Country: Canada Style: Celtic MP3 version RAR size: 1383 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1118 mb WMA version RAR size: 1688 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 270 Other Formats: APE AHX MMF DTS ADX RA FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Shifting Sands 1 4:48 Written-By – A. Drennan*, D. Spillane* Undertow 2 3:14 Written-By – D. Spillane* Shorelines 3 5:00 Written-By – A. Drennan*, D. Spillane* Call Across The Canyon 4 4:44 Written-By – D. Spillane*, L. McCormick*, T. Boland* Midnight Walker 5 4:45 Written-By – D. Spillane* Mistral 6 5:00 Written-By – A. Drennan*, D. Spillane* Rainmaker 7 4:40 Written-By – D. Spillane* Stepping In Silence 8 3:30 Written-By – D. Spillane* Morning Wings 9 4:22 Written-By – D. Spillane* Corcomroe 10 3:53 Written-By – D. Spillane* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tara Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Tara Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Tara Music Company Ltd. Published By – Sony Music Publishing Published By – Sony Music Published By – Copyright Control Credits Arranged By [Additional] – James Delaney (tracks: 2, 9), Paul Moran (tracks: 2, 9), Tony Molloy (tracks: 2, 9) Bagpipes [Uilleann], Low Whistle – Davy Spillane Bass Guitar – Joe Marcus (tracks: 4), Tony Molloy Bodhrán, Percussion – Tommy Hayes Didgeridoo, Horn [Dord Árd] – Simon O'Dwyer (tracks: 4) Drums, Cymbal, Percussion – Paul Moran Electric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Keyboards [Additional] – Anthony Drennan Electric Guitar, Percussion – Tim Boland (tracks: -

Vallelyn Phd2018.Pdf

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Beyond the tune: new Irish music Author(s) Vallely, Niall Publication date 2018 Original citation Vallely, N. 2018. Beyond the tune: new Irish music. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2018, Niall Vallely. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information Not applicable Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/7021 from Downloaded on 2021-10-10T08:36:19Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork Beyond the Tune: New Irish Music Thesis presented by Niall Vallely For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork School of Music and Theatre Head of School: Prof. Jools Gilson Supervisor: John Godfrey 2018 2 Table of Contents Declaration 4 List of accompanying musical scores and CD 5 Acknowledgements 6 Preface 7 Chapter 1 Introduction and Background 8 Education 9 Performance 12 Impact of cross-cultural music 14 Chapter 2 Context and Influences 17 Seán Ó Riada 17 Shaun Davey 18 Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin 19 Other Composers 21 Beyond Genre 23 Chapter 3 Artistic Statement 26 Compositions 27 The Red Tree 28 Sondas 35 Ó Riada Room 37 Time Flying 38 throughother 42 Nothing Else 44 Connolly’s Chair 46 Concertina Concerto 47 Conclusion 50 Appendix 1 List of compositions used in PhD 51 Appendix 2 Complete list of compositions to date 54 Discography 75 3 Bibliography 79 4 Declaration I, Niall Vallely, declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work, except as acknowledged by appropriate reference in the text. -

IMDA Septmeber 2013 Newsletter

September1 Irish Music & 2013 Meán Fómhair Dance Association 31th Year, Issue No. 9 The mission of the Irish Music and Dance Association is to support, coordinate, encourage and promote high quality activities and programs in Irish music, dance, and other cultural traditions within the community and to insure the continuation of those traditions. Mike Wallace Receives Irish Fair’s Inside this issue: 2013 Curtin-Conway Award Tune of the Month 2 Gaelic Corner 3 The Curtin-Conway Award honors Leah Curtin and Roger Conway, two of the IMDA Grant Winner 4 original organizers of the festival. The honor is presented annually to someone who September Calendar 8-9 has a long history of service or support to the Irish cultural community in the Twin Cities and/or Minnesota. The award includes a $1,000 donation by the Irish Fair to Northwoods Songs 10 the Irish cultural charity of the recipient's choice and the name of the honoree is Ceili Corner 14 placed on a plaque that is on public display at Irish On Grand. Smidirini 15 This year the Irish Fair surprised Mike Wallace before his performance on the Main Stage, and presented him with the 2013 Curtin-Conway award. In fact, he was so busy getting ready to play that he didn’t hear the announcement. Mike, a native of County Limerick, moved to Saint Paul in the mid 70’s after his band, The Irish Brigade, was invited to play a show by the Irish community. The show was a success, and after being invited back again, Mike decided to make this area his permanent home.