Remembering the Bad Old Days. Human Rights, Economic Conditions, and Democratic Performance in Transitional Regimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

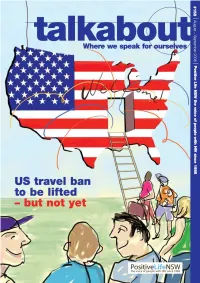

US Travel Ban to Be Lifted

US travel ban to be lifted - ••ut not yet '2 <: 2 ;j :) ~ ...J L1 < :a > no.158 August - September 2008 res 2 Editorial 3 US ban to be lifted 4 Happy Birthday HIV 6 When less is more 7 Too far gone? 8 Behind the land of smiles: Thailand 12 A warm welcome: Kate from Poz Het 14 Prevention beyond condoms: Cover Artwork: Microbicides James Gilmour www.jamespgilmour.com 16 Coming from the space of true love Contributors: James Gilmour, Lance Feeney, Neal Drinnan, 18 Need to talk to someone? Greg Page, Rob Sutherland, Kate Reakes, Kathy Triffit, Kerry Saloner, Trevor Morris, Garry Wotherspoon, Leslie, Kane Matthews, Counselling at ACON John Douglas, Ingrid Cullen, Tim Alderman 20 Dry mouth and HIV 22 It's all in the mind? Mental health 24 Olga's Personals 26 Keeping on being positive: friendships through 729 27 Fear is high, trust is low: Positive sex workers 28 Buenos Aires 30 Working out at home: Health and fitness 32 Comfort food: So can you cook? Talkabout 1 PositiveL t .. NSW the voiceof people with HIV since 1 ~ In this issue CURRENT BOARD President Jason Appleby Vice President Richard Kennedy Treasurer Bernard Kealey Secretary Russell Westacott Directors Rob Lake, Malcolm Leech, Scott Berry, David Riddell, Alan Creighton Staff Representative Hedimo Santana Our cover highlights the welcome news Changes to the time out room Chief Executive Officer (Ex Officio) about changes in the US government's Positive Life NSW has been running the Rob take attitude to HIV positive visitors. We're not CURRENT STAFF time out room at the Mardi Gras (and quite there yet but, as the article on page Chief Executive Officer Rob take usually the Sleaze) Parties for about a three shows, the US is getting closer to a Manager Organisation and Team decade and a half now. -

Association Sunday 2009 Worship Resources

ASSOCIATION SUNDAY 2009 GROWING OUR DIVERSITY ~ WORSHIP RESOURCES ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS Checklist for Organizing Your Service..................................................... 2 Hymns in Singing the Living Tradition and Singing the Journey .............. 3 Opening Words/Call to Worship .............................................................. 4 Chalice Lighting ...................................................................................... 6 Readings .................................................................................................. 8 Prayers & Meditations ........................................................................... 17 Stories for All Ages ............................................................................... 20 Books for Stories for All Ages ............................................................... 23 Sermons ................................................................................................. 25 Words for the Offering ........................................................................... 39 Closing Words/Benedictions .................................................................. 41 Original Music by UU Composers ......................................................... 43 Links to Other Resources ....................................................................... 58 CHECKLIST FOR ORGANIZING YOUR SERVICE □ Put up the Association Sunday Posters. □ Consider doing a pulpit exchange with neighboring congregations. □ Organize the service to include lay participation. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society ABCD Springer.Com

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society ABCD springer.com Highlights in Springer’s eBook Collection of the American Mathematical Society August 2009 Volume 56, Number 7 Guido Castelnuovo and Francesco Severi: NEW NEW NEW Two Personalities, Two The objective of this textbook is the Blackjack is among the most popular This second edition of Alexander Soifer’s Letters construction, analysis, and interpreta- casino table games, one where astute How Does One Cut a Triangle? tion of mathematical models to help us choices of playing strategy can create demonstrates how different areas of page 800 understand the world we live in. an advantage for the player. Risk and mathematics can be juxtaposed in the Students and researchers interested in Reward analyzes the game in depth, solution of a given problem. The author mathematical modelling in math- pinpointing not just its optimal employs geometry, algebra, trigono- ematics, physics, engineering and the strategies but also its financial metry, linear algebra, and rings to The Dixmier–Douady applied sciences will find this text useful. performance, in terms of both expected develop a miniature model of cash flow and associated risk. mathematical research. Invariant for Dummies 2009. Approx. 480 p. (Texts in Applied Mathematics, Vol. 56) Hardcover 2009. Approx. 140 p. 23 illus. Hardcover 2nd ed. 2009. XXX, 174 p. 80 illus. Softcover page 809 ISBN 978-0-387-87749-5 7 $69.95 ISBN 978-1-4419-0252-8 7 $49.95 ISBN 978-0-387-74650-0 7 approx. $24.95 For access check with your librarian Waco Meeting page 879 A Primer on Scientific Data Mining in Agriculture Explorations in Monte Programming with Python A. -

Pre-Owned 1970S Sheet Music

Pre-owned 1970s Sheet Music 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deterioration Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside.Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year Year of print.Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS?You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even Wings or “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. 1970s TITLE WRITER & COMPOSER CONDITION PHOTO YEAR $7,000 and you Hugo & Luigi/George David Weiss ex The Stylistics 1977 ABBA – greatest hits Album of 19 songs from ex Abba © 1992 B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus After midnight John J.Cale ex Eric Clapton 1970 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Again and again Richard Parfitt/Jackie Lynton/Andy good Status Quo 1978 Bown Ain‟t no love John Carter/Gill Shakespeare ex Tom Jones 1975 Airport Andy McMaster ex The Motors 1976 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a ©1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and Johnny -

The High Costs of Electricity Deregulation by FOHREST WILDER JUNE 30, 2006 Thetexas Observer Dialogue

JUNE 30, 2006 $2.25 OPENING THE EYES OF TEXAS FOR FIFTY ONE YEARS lifikiktnie1111111H111 The High Costs of Electricity Deregulation by FOHREST WILDER JUNE 30, 2006 TheTexas Observer Dialogue FEATURES FEAR AND LOATHING The fear and loathing in San Antonio article ["Fear and Loathing in San Antonio: OVERRATED 6 Republicans get riled up over immigration and taxes at their state convention," Deregulation was supposed to lower June 16] appeared to originate more from the author of the article, rather than Texans' electric bills. Instead, rates are from those Americans about whom he wrote, who are interested in seeing the through the roof laws of the United States and the laws of Texas upheld. I thought we had all the by Forrest Wilder left-wing wackos out here on the left coast. I'm encouraged to know that there's diversity in Texas. Yee Haw! THE FIGHT FOR RELEVANCE 10 Len Turner Democrats look for signs of hope at San Jose, CA their state convention. by Dave Mann FRAGMENTS OF ENGLISH 18 DEPARTMENT OF BACK - PATTING Texas has never been monolingual, and it never will be. We're proud to announce that Dave Mann's September 23, 2005, story about by Michael Erard nursing home abuse, "A Death in McAllen," was awarded the first prize for Investigative Reporting by the Association of Alternative Newsweeldies at the AAN annual convention earlier this month. Dave also received an DEPARTMENTS Honorable Mention in the category "News Story Long Form" for his March 18, 2005, story "Getting Plucked" about the poultry farm business. DIALOGUE 2 Contributing writer Andrew Wheat received third place for political columns EDITORIAL 3 ("A Homeowner Nails Bob Perry," May 13, 2005; "Muckraker Katrina;' Ah - ha! October 7, 2005; and "Delay's Beautiful Laundrette;' October 21, 2005). -

Spring 2007 Newsletter

Forest News Georgia ForestWatch Quarterly Newsletter Spring 2007 Hope for the Page 4 Hemlocks Inside This Issue From the Director ....................... 2 An Evening Under the “Green Does Restoration Forestry Roof” ........................................ 6 Have To Pay? ..............................15 Georgia ForestWatch History, Part 3: Developing a Unique President Bush and His Forest Whitewater Drops Case For Identity ....................................... 3 Legacy ....................................... 7 Now ...........................................16 Hope for the Hemlocks: UGA New Member Welcome ........... 12 Upper Chattooga Likely to Opens Predator Beetle Lab ......... 4 Suffer From Boating ...................17 Marie Mellinger (1914-2006) .. 14 Bigger, Better Native Plant Sale .. 5 Chattooga River District Report ..19 From The Director The mountain hiking cure Wayne Jenkins Executive Director You know how it is. The past few weeks have been really onto these escarpments must rise, cool and then drop more busy, stressful even. You’re staring down the barrel of another rain (between 80 to 100 inches annually) than that falling on week busier than the two you just survived. A little cranky, the adjoining lower valleys, creating a kind of lush peak island sluggish. You’re grumpy and just not feeling too well. Maybe affect. Deep black soils support some fine recovering second the flu is coming on. What to do? growth hardwood forests and one area in particular drew my attention. The largest contiguous block of old growth forest Over 50 now, I’ve been here often enough to know what yet located on the Chattahoochee lies to the south of Grassy I need. What works for me to recharge the batteries, and Mountain and wraps around to west and then north of the gain a most-necessary attitude adjustment. -

1969 May 3 – UK Top 50

Wk 18 – 1969 may 3 – UK Top 50 1 1 2 GET BACK Beatles 2 3 5 GOODBYE Mary Hopkin 3 2 7 ISRAELITES Desmond Dekker & Aces 4 4 7 PINBALL WIZARD Who 5 8 6 COME BACK AND SHAKE ME Clodagh Rodgers 6 13 5 CUPID Johnny Nash 7 11 8 HARLEM SHUFFLE Bob & Earl 8 9 10 THE WINDMILLS OF YOUR MIND Noel Harrison 9 6 12 I HEARD IT THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE Marvin Gaye 10 7 8 BOOM BANG-A-BANG Lulu 11 21 3 MAN OF THE WORLD Fleetwood Mac 12 5 13 GENTLE ON MY MIND Dean Martin 13 16 5 ROAD RUNNER Junior Walker & All-Stars 14 10 8 IN THE BAD OLD DAYS Foundations 15 27 2 MY SENTIMENTAL FRIEND Herman's Hermits 16 17 5 MY WAY Frank Sinatra 17 14 7 I DON'T KNOW WHY / MY CHERIE AMOUR Stevie Wonder 18 12 10 I CAN HEAR MUSIC Beach Boys 19 15 9 GAMES PEOPLE PLAY Joe South 20 29 3 BEHIND A PAINTED SMILE Isley Brothers 21 22 10 PASSING STRANGERS Sarah Vaughan & Billy Eckstine 22 19 7 HELLO WORLD Tremeloes 23 34 4 COLOUR OF MY LOVE Jefferson 24 44 3 DIZZY Tommy Roe 25 - 1 THE BOXER Simon & Garfunkel 26 24 5 MICHAEL AND THE SLIPPER TREE Equals 27 18 9 SORRY SUZANNE Hollies 28 20 4 BADGE Cream 29 32 2 I'M LIVIN' IN SHAME Diana Ross & Supremes 30 23 12 MONSIEUR DUPONT Sandie Shaw 31 25 10 GOOD TIMES (BETTER TIMES) Cliff Richard 32 37 3 PLASTIC MAN Kinks 33 45 3 BLUER THAN BLUE Rolf Harris 34 30 13 WHERE DO YOU GO TO (MY LOVELY) Peter Sarstedt 35 35 2 AQUARIUS / LET THE SUNSHINE IN 5th Dimension 36 26 9 GET READY Temptations 37 - 1 RAGAMUFFIN MAN Manfred Mann 38 28 6 THE WALLS FELL DOWN Marbles 39 - 19 PLEASE DON'T GO Donald Peers 40 31 10 IF I CAN DREAM Elvis Presley 41 - 4 WITH PEN IN HAND Vikki Carr 42 41 2 SURROUND YOURSELF WITH SORROW Cilla Black 43 - 1 MY FRIEND Roy Orbison 44 - 1 YOU'VE MADE ME SO VERY HAPPY Blood Sweat & Tears 45 43 9 DON JUAN Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick And Tich 46 38 3 CROSSTOWN TRAFFIC Jimi Hendrix 47 42 11 NOWHERE TO RUN Martha & Vandellas 48 33 11 FIRST OF MAY Bee Gees 49 40 13 THE WAY IT USED TO BE Engelbert Humperdinck 50 46 5 EVERYDAY PEOPLE Sly & Family Stone . -

Previous Eurovision Winners and UK Entries

YEAR LOCATION/Venue WINNING ENTRY U.K. ENTRY Date Presenter(s) COUNTRY SONG TITLE PERFORMER(S) SONG TITLE PERFORMER(S) PLACED 1956 LUGANO SWITZERLAND Refrain Lys Assia - no entry - May 24 Teatro Kursaal Lohengrin Filipello 1957 FRANKFURT-AM-MAIN NETHERLANDS Net als toen Corry Brokken All Patricia Bredin 7th March 3 Großen Sendesaal des Hessischen Rundfunks Anaïd Iplikjan 1958 HILVERSUM FRANCE Dors mon amour André Claveau - no entry - March Avro Studios 12 Hannie Lips 1959 CANNES NETHERLANDS Een beetje Teddy Scholten Sing little birdie Pearl Carr and Teddy 2nd March Palais des Festivals Johnson 11 Jacqueline Joubert 1960 LONDON FRANCE Tom Pillibi Jacqueline Boyer Looking high, high, high Bryan Johnson 2nd March Royal Festival Hall 29 Catherine Boyle 1961 CANNES LUXEMBOURG Nous les amoureux Jean-Claude Pascal Are you sure? The Allisons 2nd March Palais des Festivals 18 Jacqueline Joubert 1962 LUXEMBOURG FRANCE Un premier amour Isabelle Aubret Ring-a-ding girl Ronnie Carroll 4th March Villa Louvigny 18 Mireille Delannoy 1963 LONDON DENMARK Dansevise Grethe and Jørgen Say wonderful things Ronnie Carroll 4th March BBC Television Centre Ingmann 23 Catherine Boyle 1964 COPENHAGEN ITALY Non ho l’età Gigliola Cinquetti I love the little things Matt Monro 2nd March Tivoli Gardens Concert Hall 21 Lotte Wæver 1965 NAPLES LUXEMBOURG Poupée de cire, poupée France Gall I belong Kathy Kirby 2nd March RAI Concert Hall de son 20 Renata Mauro 1966 LUXEMBOURG AUSTRIA Merci Chérie Udo Jürgens A man without love Kenneth McKellar 9th March 5 CLT Studios, Villa Louvigny Josiane Shen 1967 VIENNA UNITED KINGDOM Puppet on a string Sandie Shaw Puppet on a string Sandie Shaw 1st April 8 Wiener Hofburg Erica Vaal 1968 LONDON SPAIN La la la Massiel Congratulations Cliff Richard 2nd April 6 Royal Albert Hall Katie Boyle 1969 MADRID SPAIN Vivo cantando Salomé Boom bang-a-bang Lulu 1st March Teatro Real UNITED KINGDOM Boom bang-a-bang Lulu 29 Laurita Valenzuela NETHERLANDS De Troubadour Lennie Kuhr FRANCE Un jour, un enfant Frida Boccara YEAR LOCATION/Venue WINNING ENTRY U.K. -

SURVIVAL of the STREETS - Snake Plissken, the Cro-Mags, and The

SURVIVAL OF THE STREETS - Snake Plissken, the Cro-Mags, and the... http://www.viceland.com/int/v16n9/htdocs/survival-of-the-streets-137.... HOME DOs & DON'Ts Magazine MUSIC FASHION PHOTOS VBS.TV CONTESTS Current issue Archive Subscribe Newsletter MAGAZINE NEWSLETTER SURVIVAL OF THE STREETS DOS & DON'TS Snake Plissken, the Cro-Mags, and the Persistence of Megatoilet Nostalgia BY SAM MCPHEETERS, ILLUSTRATIONS BY CHRISTY KARACAS “Its actually awesome that Aunt Ruth kicked me out of the house ‘cause now I get to wear whatever I want, whenever I want.” Enlarge/Comments DOs & DON'Ts You can tell you've picked the wrong borough to live in when even the homeless can't stop themselves from shitting on it. Enlarge/Comments DOs & DON'Ts 1 av 5 2011-10-02 19:18 SURVIVAL OF THE STREETS - Snake Plissken, the Cro-Mags, and the... http://www.viceland.com/int/v16n9/htdocs/survival-of-the-streets-137.... ALSO BY SAM MCPHEETERS MODERN-DAY FASHION BUM-OUTS Today’s Trends Are Tomorrow’s Giggles THE CORPSE Home Cryonics in the Smirk Age THE DESSERT PSYCHO Punk Drummer Transforms Into World-Class ... GLENN DANZIG Most performers have to span a gap betwee... See all articles by this contributor New York City’s comeback has been an odd thing to watch from afar. When I moved out of Manhattan in 1990, the city was every inch the pee-smelling woe zone I’d known since childhood. When I returned this spring, I couldn’t even find key graffiti on subway windows. Taxi rides are like something from a science-fiction movie now—not because New York cabs have televisions in them, but because these televisions actually work. -

Sturgis Rider Daily 4 of 8 Tonight’S Headliner: Tuesday Aug

® FREE STURGIS RIDER DAILY 4 OF 8 TONIGHT’S HEADLINER: TUESDAY AUG. 9, 2016 INSIDE HALL OF FAME Page 4 EASYRIDERS AUCTION Page 11 Fast and erce racing fury … SPORTSTER SHOWDOWN Page 13 THE MOTO STAMPEDE! STURGIS WEATHER Tues 8/9 Wed 8/10 91/73 91/63 Mostly Sunny Partly Cloudy Courtesy of weather.com STURGIS BUFFALO CHIP’S WOLFMAN JACK STAGE TONIGHT Roving Reporter Roady Loner has been around the 10 PM block and that’s no lie. As a seasoned road-dog, he’s seen CHEAP TRICK it all — or just about. So we put him on the case of the 8:30 PM Moto Stampede. It’s just the thing to snap old Roady back to racing’s heyday — when men were men and TEXAS HIPPIE women were okay with it. COALITION Super Hooligan Racing is hard scrabble, bar-to-bar action that’s electrifying to watch and addicting to do. t goes without saying that rock music and motor- Be in the Buffalo Chip amphitheater tomorrow, Wednesday, August 10, and you’ll agree. 7 PM cycles go together like pinstripes and metal ake. THE GRIZZLED MIGHTY Even before the days of all these 300-watt ste- with Mothership at Bikini Beach follow. Ireos on two wheels, the spirit behind a good groove at’s just the set-up, though. Because throw- TOMORROW was playing in your head while you roared down the ing down all day Wednesday in the Bu alo Chip 10:30 PM blacktop, mile after mile. Or was that just a ash- Amphitheater, the Moto Stampede brings the misty back? red fury of smoky, dirty racing right into your lap. -

Texas Lesbian Conference

MANY KINDS OF POWER THE" 6TH ANNUAL TEXAS LESBIAN CONFERENCE MAY 21 - 23,1993 STOUFFER PRESIDENTE HOTEL HOUSTON POINSETIIA I ,I AZALEA, I I WOMEN MEN I I I -JI.- JUSTIN'S RESTAURANT & LOUNGE ELEVATOR AUDIO VISUAL ESCALATORS GREENWAY II >- III T III -' .-.:' FOYER s ::; ----------------------1 o Z aa:.. 0 :to (fJ ~ GREENWAY I CENTURY II CONCOURSE LEVEL Welcome to Houston,Texasand the TexasLesbian Conference 19931 We are so glad that you decided to join us. Thisyear's conference is in memory and honor of the poet and essayist Audre Lorde. Our theme, "Many Kinds of Power" ,was taken from her essay" Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power." Using the erotic as a metaphor of the lifeforce of womyn and our creative energy, Lorde encourages us to reclaim language, history, dancing, loving, work and lives, and in doing so, to reclaim ourselves. To be in touch with our power isto move beyond fear. To be in touch with our power isto connect with others, to connect with our deepest knowledge, and to connect with ourselves. As Audre Lorde wrote, "recognizing such power within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world." The Planning Committee hopes that this weekend will offer you many opportunities to touch your power and in doing so, to celebrate yourself. • news • feature articles • advice column • poetry • book reviews • humoristNancy Ford • and much. much morel $2 Sample Copy $12 Six Month Subscription $24 Twelve Month Subscription P.O. Box 856 Lubbock, TX 79408 (806) 797-9647 3 SCHEDULE Friday, May 21st 5:00pm -

BY Kathleen Stansberry, Janna Anderson and Lee Rainie

FOR RELEASE OCTOBER 28, 2019 BY Kathleen Stansberry, Janna Anderson and Lee Rainie FOR MEDIA OR OTHER INQUIRIES: Lee Rainie, Director, Internet and Technology Research Kathleen Stansberry, Elon’s Imagining the Internet Center Shawnee Cohn, Communications Manager 202.419.4372 www.pewresearch.org RECOMMENDED CITATION Pew Research Center, October 2019, “Experts Optimistic About the Next 50 Years of Digital Life” 1 PEW RESEARCH CENTER About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. It does not take policy positions. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis and other data-driven social science research. The Center studies U.S. politics and policy; journalism and media; internet, science and technology; religion and public life; Hispanic trends; global attitudes and trends; and U.S. social and demographic trends. All of the center’s reports are available at www.pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. For this project, Pew Research Center worked with Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center, which helped conceive the research and collect and analyze the data. © Pew Research Center 2019 www.pewresearch.org 2 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Experts Are Optimistic About the Next 50 Years of Life Online The year 1969 was a pivot point in culture, science and technology. On Jan. 30, the Beatles played their last show. On July 20, the world watched in awe as Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin become the first humans to walk on the moon.