Spectacles of Illegality: Mapping Ethiopia's Show Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Findet Äthiopien Wege Aus Der Krise? Die Folgenden Quellen Wurden in Dem Heft Verwendet (Originale Teilweise Geringfügig Gekürzt)

DEUTSCH-ÄTHIOPISCHER VEREIN E.V. GERMAN ETHIOPIAN ASSOCIATION INFORMATIONSBLÄTTER 3/2017 Findet Äthiopien Wege aus der Krise? Die folgenden Quellen wurden in dem Heft verwendet (Originale teilweise geringfügig gekürzt) Political unrest simmering in Ethiopia ………………………………………………………… 1 Merga Yonas Bula, Deutsche Welle, 10.2.2017 Opposition parties to negotiate with EPRDF in unison ……………………………………. 3 Ethiopian News Agency ENA, 9.2.2017 Timely Ethiopian teachers’ warning against TPLF divisiveness …………………………. 3 Ethiopia Observatory, 9.2.2017 Public ultimate guarantor of nation’s peace and security ………………………………… 4 Ethiopian Reporter, Editorial, 4.2.2017 Ethiopia: A Gathering Political Storm ………………………………………………………… 5 Alem Mamo, Nazret.com 1.2.2017 Ethiopia claims success in quashing wave of anti-government unrest ………………… 6 John Aglionby, Financial Times in Addis Ababa, 1.2.2017 Ethiopia: The Slow Death of a Civilian Government and the Rise of a Military Might … 7 Addis Standard, 24.1.2017 A Wish List for Successful Opposition and Government Negotiations ……………….. 11 Solomon Gebreselassie, Ethiopian Observer, 22.1.2017 Salvaging Political Pluralism ………………………………………………………………….. 13 Asrat Seyoum, Ethiopian Reporter, 21.1.2017 Analysis: Inside the controversial EFFORT ………………………………………………. 14 Oman Uliah, Special to Addis Standard, 16.1.2017 Ethiopia: Justified Fears ………………………………………………………………………. 18 Desta Heliso, Nazret.com, 30.12.2016 Ethiopia in the eyes of a veteran scholar ………………………………………………….. 20 Ethiopian Reporter, 17.12.2016, Interview by Tibebeselassie Feeling the Pulse of the People ……………………………………………………………… 24 Ethiopian Reporter, Editorial, 10 Dec 2016, by Staff Reporter Ethiopia at a crossroads as it feels the strain of civil unrest ………………………….. 26 James Jeffrey, Irish Times, Addis Ababa, 9 December 2016 New television channels in Ethiopia may threaten state control ………………………. -

Ethiopia, the TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at WMU Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU International Conference on African Development Center for African Development Policy Research Archives 8-2001 Ethiopia, The TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive Part of the African Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Milkias, Paulos, "Ethiopia, The TPLF nda Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor" (2001). International Conference on African Development Archives. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive/4 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for African Development Policy Research at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on African Development Archives by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETHIOPIA, TPLF AND ROOTS OF THE 2001 * POLITICAL TREMOR ** Paulos Milkias Ph.D. ©2001 Marianopolis College/Concordia University he TPLF has its roots in Marxist oriented Tigray University Students' movement organized at Haile Selassie University in 1974 under the name “Mahber Gesgesti Behere Tigray,” [generally T known by its acronym – MAGEBT, which stands for ‘Progressive Tigray Peoples' Movement’.] 1 The founders claim that even though the movement was tactically designed to be nationalistic it was, strategically, pan-Ethiopian. 2 The primary structural document the movement produced in the late 70’s, however, shows it to be Tigrayan nationalist and not Ethiopian oriented in its content. -

Human Rights Violations in Ethiopia

/ w / %w '* v *')( /)( )% +6/& $FOUFSGPS*OUFSOBUJPOBM)VNBO3JHIUT-BX"EWPDBDZ 6OJWFSTJUZPG8ZPNJOH$PMMFHFPG-BX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by University of Wyoming College of Law students participating in the Fall 2017 Human Rights Practicum: Jennie Boulerice, Catherine Di Santo, Emily Madden, Brie Richardson, and Gabriela Sala. The students were supervised and the report was edited by Professor Noah Novogrodsky, Carl M. Williams Professor of Law and Ethics and Director the Center for Human Rights Law & Advocacy (CIHRLA), and Adam Severson, Robert J. Golten Fellow of International Human Rights. The team gives special thanks to Julia Brower and Mark Clifford of Covington & Burling LLP for drafting the section of the report addressing LGBT rights, and for their valuable comments and edits to other sections. We also thank human rights experts from Human Rights Watch, the United States Department of State, and the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office for sharing their time and expertise. Finally, we are grateful to Ethiopian human rights advocates inside and outside Ethiopia for sharing their knowledge and experience, and for the courage with which they continue to document and challenge human rights abuses in Ethiopia. 1 DIVIDE, DEVELOP, AND RULE: HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN ETHIOPIA CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW & ADVOCACY UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING COLLEGE OF LAW 1. PURPOSE, SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY 3 2. INTRODUCTION 3 3. POLITICAL DISSENTERS 7 3.1. CIVIC AND POLITICAL SPACE 7 3.1.1. Elections 8 3.1.2. Laws Targeting Dissent 14 3.1.2.1. Charities and Society Proclamation 14 3.1.2.2. Anti-Terrorism Proclamation 17 3.1.2.3. -

Dismantling Dissent Intensified Crackdown on Free Speech in Ethiopia

DISMANTLING DISSENT INTENSIFIED CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH IN ETHIOPIA Amnesty International Publications First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AFR 25/011/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. CONTENTS Summary ..........................................................................................................................5 -

Bibliographic Guide to Further Reading

BIBLIOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO FURTHER READING The historical, memoir, travel, and technical literature on Ethiopia is immense and continually growing. A complete bibliography would require a very thick volume. Included below are most of the major books cited in the text. Journal articles, pamphlets and monographs are not included. Many worthwhile books from my own collection not specifically referenced in the footnotes have been added. Books in languages other than English, German, French, Italian and Portu guese are not listed. Among the most valuable sources for research on Ethiopia are the proceedings of the triennial International Ethiopian Studies Conferences (IESC), the most recent of which were held in East Lansing, Michigan in September 1994 and in Kyoto,Japan in Decem ber 1997. The former produced 2,372 pages of papers published as New Trends in Ethiopian Studies (2 vols. Red Sea Press, No. 1994). The latter resulted in 2,345 pp. of papers published as Ethiopia in Broader Perspective (Shokado, Kyoto, 1997, 3vols). The 14th IESC is scheduled to take place in Addis Ababa in November 2000. Many other volumes of conference proceedings have been published in Ethiopia and elsewhere during the past three decades. With only a few except ions, these have not been listed below. HISTORY AND CULTURE, GENERAL Berhanou Abebe, Historie de lithiopie d'Axoum ala revolution, Maison neuve et Larose, Paris, 1998. E. A. Wallis Budge, History ofEthiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, Methuen, London, 192R David Buxton, The Abyssinians, Thames & Hudson, London, 1970. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski, Ethiopia sAccess to the Sea, EJ. Brill, Leiden, 1985. Jean Doresse, Ethiopia, Elee, London, 1959. -

Democracy Under Threat in Ethiopia Hearing Committee

DEMOCRACY UNDER THREAT IN ETHIOPIA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 9, 2017 Serial No. 115–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–585PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:13 Apr 20, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\030917\24585 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. -

CONFLITOS, ATORES, AGENDAS E AMEAÇAS

SÉRIE AFRICANA CONFLITOS, ATORES, AGENDAS e AMEAÇAS © Nilton César Fernandes Cardoso 1ª edição: 2020 Direitos reservados desta edição: CEBRAFRICA – UFRGS [email protected] | ufrgs.br/cebrafrica Revisão: Paulo Fagundes Visentini Projeto Gráfico: Walter Diehl e João Corrêa Capa: Walter Diehl Diagramação: Walter Diehl e Luana Margarete Geiger Impressão: Gráfica UFRGS Apoio: Reitoria UFRGS e Editora UFRGS Série Africana Conselho editorial: Analúcia Danilevicz Pereira (UFRGS) - coordenadora do CEBRAFRICA Paulo Fagundes Visentini (UFRGS) - coordenador do NERINT José Carlos dos Anjos (UFRGS - UniCV) Luiz Dario Teixeira Ribeiro (UFRGS) Marco Cepik (UFRGS) Alfa Diallo (UFDG) Pio Penna Filho (UnB) Mamoudou Gazibo (Univ. de Montréal - Canada) Gladys Lechini (U.N. Rosário - Argentina) Gerhard Seibert (UFBA) Hilário Cau (ISRI - Maputo, Moçambique) Loft Kaabi (ITES - Cartago, Tunísia) Chris Landsberg (Univ. de Joanesburgo - África do Sul) [T]he peace of Africa is to be assured by the exertions of Africans themselves. The idea of a “Pax Africana” is the specifically military aspect of the principle of continental jurisdiction. ALI A. MAZRUI SUMÁRIO PREFÁCIO 11 INTRODUÇÃO 15 [ 1 ] ÁFRICA NO SISTEMA INTERNACIONAL: ESTRUTURA, AGÊNCIA E ‘DEPENDÊNCIA’ 23 1.1 Estabelecimento do Sistema de Relações Interafricanas (1946–1970) 26 1.2 Reordenamento, Crises e Tensões (1970–1990) 39 1.3 Vazio Estratégico, Marginalização e Crise dos Estados (1991–2000) 47 1.4 Renascimento e Reafirmação da África (2000–2017) 55 [ 2 ] CONSTRUÇÃO DE ESTADO E FORMAÇÃO DO CHIFRE DA -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Addis, Amsalu K.; Asongu, Simplice; Zhu, Zuping; Addis, Hailu Kendie; Shifaw, Eshetu Working Paper The recent political situation in Ethiopia and rapprochement with Eritrea AGDI Working Paper, No. WP/20/036 Provided in Cooperation with: African Governance and Development Institute (AGDI), Yaoundé, Cameroon Suggested Citation: Addis, Amsalu K.; Asongu, Simplice; Zhu, Zuping; Addis, Hailu Kendie; Shifaw, Eshetu (2020) : The recent political situation in Ethiopia and rapprochement with Eritrea, AGDI Working Paper, No. WP/20/036, African Governance and Development Institute (AGDI), Yaoundé This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/228008 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu A G D I Working Paper WP/20/036 The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea 1 Forthcoming: African Security Review Amsalu K. -

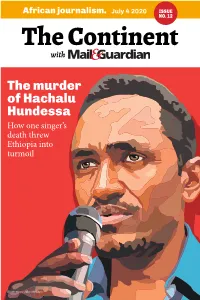

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side). -

Ethiopia Eritrea Somalia Djibouti

COUNTRY REPORT Ethiopia Eritrea Somalia Djibouti 2nd quarter 1996 The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent Street, London SW1Y 4LR United Kingdom The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For over 40 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The EIU delivers its information in four ways: through subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through specific research reports, whether for general release or for particular clients; through electronic publishing; and by organising conferences and roundtables. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York Hong Kong The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent Street The Economist Building 25/F, Dah Sing Financial Centre London 111 West 57th Street 108 Gloucester Road SW1Y 4LR New York Wanchai United Kingdom NY 10019, USA Hong Kong Tel: (44.171) 830 1000 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Tel: (852) 2802 7288 Fax: (44.171) 499 9767 Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 Electronic delivery EIU Electronic Publishing New York: Lou Celi or Lisa Hennessey Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248 London: Moya Veitch Tel: (44.171) 830 1007 Fax: (44.171) 830 1023 This publication is available on the following electronic and other media: Online databases CD-ROM Microfilm FT Profile (UK) Knight-Ridder Information World Microfilms Publications (UK) Tel: (44.171) 825 8000 Inc (USA) Tel: (44.171) 266 2202 DIALOG (USA) SilverPlatter (USA) Tel: (1.415) 254 7000 LEXIS-NEXIS (USA) Tel: (1.800) 227 4908 M.A.I.D/Profound (UK) Tel: (44.171) 930 6900 Copyright © 1996 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. -

The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea Addis, Amsalu and Asongu, Simplice and Zuping, Zhu and Addis, Hailu Kendie and Shifaw, Eshetu January 2020 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/107090/ MPRA Paper No. 107090, posted 10 Apr 2021 14:14 UTC A G D I Working Paper WP/20/036 The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea 1 Forthcoming: African Security Review Amsalu K. Addis School of Economics and Management Fuzhou University, Fuzhou, China P.O.Box: 2 Xueyuan Road, Minhou, Fujian, Fuzhou,350116, CN E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +86– 152 8007 6673 Simplice Asongu African Governance and Development Institute, P.O. Box 8413, Yaoundé, Cameroon E-mails: [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +32473613172 Zhu Zuping School of Economics and Management Fuzhou University, Fuzhou, China E-mails: [email protected] Tel: +86-137 0697 6655 Hailu Kendie Addis Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute, Bahir Dar –Ethiopia E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +251-918 711082 Eshetu Shifaw Wollo University, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Wollo – Ethiopia E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +251-912777193 1 This working paper also appears in the Development Bank of Nigeria Working Paper Series. 1 2020 African Governance and Development Institute WP/20/036 Research Department The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea Amsalu K. Addis, Simplice Asongu, Zhu Zuping, Hailu Kendie Addis & Eshetu Shifaw January 2020 Abstract The aim of this article is designed to provide an overview of the historical and contemporary relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea as well as to examine the recent geopolitical situation and the perception of local people in Ethiopia.