'The Bastard Child of Nobody'?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

The Inspector General of Government and the Question of Political Corruption in Uganda

Frustrated Or Frustrating S AND P T EA H C IG E R C E N N A T M E U R H H URIPEC FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA Daniel Ronald Ruhweza HURIPEC WORKING PAPER NO. 20 November, 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA Daniel R. Ruhweza HURIPEC WORKING PAPER No. 20 NOVEMBER, 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA aniel R. Ruhweza Copyright© Human Rights & Peace Centre, 2008 ISBN 9970-511-24-8 HURIPEC Working Paper No. 20 NOVEMBER 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...................................................................................... i LIST OF ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS......................………..………............ ii LIST OF LEGISLATION & INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS….......… iii LIST OF CASES …………………………………………………….. .......… iv SUMMARY OF THE REPORT AND MAIN RECOMMENDATIONS……...... v I: INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………........ 1 1.1 Working Definitions….………………............................................................... 5 1.1.1 The Phenomenon of Corruption ……………………………………....... 5 1.1.2 Corruption in Uganda……………………………………………….... 6 II: RATIONALE FOR THE CREATION OF THE INSPECTORATE … .... 9 2.1 Historical Context …………………………………………………............ 9 2.2 Original Mandate of the Inspectorate.………………………….…….......... 9 2.3 -

Start Journal Issue No 001 Oct

start A Critical Art Journal Issue No. 001 | October - December 2007 1 Foreword Dear art lovers and art lovers to be, I am very pleased to have been asked by the Kampala Arts Trust, representing Ugandan artists, to introduce the first edition of the Journal St.ART. As German Ambassador to Uganda it is a privilege for me to promote cultural exchange between Uganda and Germany. I am delighted to see the Ugandan art scene so pluralistic and active. I discovered impressive Ugandan paintings and sculptures, music and dance performances in different styles, traditional as well as modern. It seems that Ugandans can draw on unlimited artistic sources. This makes cultural exchange very easy, because in Germany, too, art scene is very alive. Art lives from being seen and admired. This seems to be the biggest challenge that the Ugandan painters and sculptors have to face. Too few Ugandans get a chance to see the works and performances of artists and hence do not get an emotional and intellectual access to them. The Ugandan painters and sculptors have developed innovating ideas to change this situation. In May 2007, backed by the Ugandan German Cultural Society (UGCS), they organized a street festival in Kamwokya. There, not only they presented a huge variety of artistic activities, but visitors were invited to take an active part and create pieces of art together with artists. You can learn more on this festival in this issue of “St. ART”. I welcome the courage of the editors of “START” to start this magazine for art lovers. -

2000 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 23, 2001

Uganda Page 1 of 21 Uganda Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2000 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 23, 2001 President Yoweri Museveni, elected to a 5-year term in 1996 under the 1995 Constitution, continued to dominate the Government. He has ruled since 1986 through the National Resistance Movement, legislatively reorganized and renamed as "The Movement" in 1995. The Constitution provides for a 281-member unicameral parliament and an autonomous, independently elected president. The 1996 presidential and parliamentary elections were peaceful and orderly, but election conditions, including restrictions on political party activities, led to a flawed election process. The Constitution formally extended the one-party movement form of government for 5 years and severely restricted political activities. In June a national referendum on the role of political parties resulted in the indefinite extension of the Movement form of government. The referendum process was flawed by restrictions on political party activities and unequal funding. The Parliament acted with continued independence and assertiveness during the year, although Movement supporters remained in control of the legislative branch. Parliamentarians were elected to 5-year terms in 1996. The judiciary generally is independent, but is understaffed and weak; the President has extensive legal powers. The Uganda People's Defense Force (UPDF) is the key security force. The Constitution provides for civilian control of the UPDF, with the President designated as commander in chief. The UPDF remained active due to the continued instability in the north and west and because of the country's involvement in the conflict in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Country Advice Uganda – UGA36312 – Central Civic Education Committee

Country Advice Uganda Uganda – UGA36312 – Central Civic Education Committee – Democratic Party – Uganda Young Democrats – Popular Resistance Against Life Presidency – Buganda Youth Movement 9 March 2010 Please provide information on the following: 1. Leadership, office bearers of the Central Civic Education Committee (CVEC or CCEC) since 1996. The acronym used in sources for the Central Civic Education Committee‟s is CCEC. As of 10 January 2008, the CCEC was initially headed by Daudi Mpanga who was the Minister for Research for the south central region of Buganda according to Uganda Link.1 On 1 September 2009 the Buganda Post reported that the committee was headed by Betty Nambooze Bakireke.2 She is commonly referred to as Betty Nambooze. Nambooze was Democratic Party spokeswoman.3 The aforementioned September 2009 Buganda Post article alleged that Nambooze had been kidnapped and tortured by the Central Government for three days. She had apparently been released due to international pressure and, according to the Buganda Kingdom‟s website, the CCEC had resumed its duties.4 In a November 2009 report, the Uganda Record states that Nambooze had subsequently been arrested, this time in connection with the September 2009 riots in Kampala.3 The CCEC was created by the Kabaka (King) of Buganda in late 2007 or early 2008 according to a 9 January 2008 article from The Monitor. The CCEC was set up with the aim to “sensitise” the people of Buganda region to proposed land reforms.5 The previously mentioned Buganda Post article provides some background on the CCEC: The committee, which was personally appointed by Ssabasajja Kabaka Muwenda Mutebi, is credited for awakening Baganda to the reality that Mr. -

Reasons for the Rise of Plastic Pollution on the Streets of Kampala and the Existing Measures That Have Been Taken by Kampala City Council (KCCA)

Reasons for the rise of plastic pollution on the streets of Kampala and the existing measures that have been taken by Kampala City Council (KCCA). Ssenyonjo Edrine, Muwesi Patrick Daniel, Kasaga Derick, Opollo Canowira Emmanuel, Mr. Muteganda Amon (supervisor). Group 46, Bachelors of Software Engineering, Department of Networks, College of computing and Information Science, Makerere University. Abstract Plastic waste management is one of the major environmental problems facing city municipalities today. In Kampala City, like other urban centers in Uganda, this important service is based on the local government's centralized collection, transportation and disposal strategy. Currently this approach has proved to be inefficient due to the heavy financial requirements involved. There is an urgent need to provide for the safe disposal of the plastic waste generated by urban residents and businesses. The increase in urban, economic and industrial activities, as well as the resultant population increase have led to an increase in the quantity of plastic waste generated. One method employed in collecting data included field trips to dump sites which are used by the Kampala City Council Authority (KCC). Monitoring of collection points both in the Central Business areas and in residential areas was also used. Interviews were conducted on personnel, both in the Kampala City Council Authority (KCCA) and on residents in high, medium and low density residential areas. The results of the study indicate that alternative means to plastic disposal need to be developed with population growth and economic development in mind. This study is an attempt to analyze the management options that the KCC has and how effective our Automated Plastic Disposal system will be. -

Republic of Uganda Facts and Data (June 2011)

KAS Office Uganda www.kas.de/uganda/en/ Republic of Uganda Facts and Data (June 2011) © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Capital Kampala Form of government Presidential Republic President / Head of State Yoweri Kaguta Museveni Official Language Swahili and English Administration 112 districts in 4 regions (Eastern, Western, Northern and Central Region) Geographical borders Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, (South)Sudan Area 241,038 sq km1 Popoulation 34.612.250 Ugandans, thereof: Baganda 16.9%, Banyakole 9.5%, Basoga 8.4%, Bakiga 6.9%, Iteso 6.4%, Langi 6.1%, Acholi 4.7%, Bagisu 4.6%, Lugbara 4.2%, Bunyoro 2.7%, other 29.6% Population density 113 inhabitants per km² Population growth 3.576% Human Development Index 0.422 (rank 143 out of 169)2 Gross Domestic Product 17.12 billion US$ (GDP) GDP per capita (PPP) 1.200 US$ Currency 1 USD = 2.408,127 Uganda-Schilling (UGX)3 Independence 9th October 1962 Religion Roman Catholic 41.9%, Protestant 42% (Anglican 35.9%, Pentecostal 4.6%, Seventh Day Adventist 1.5%), Muslim 12.1%, other 3.1%, none 0.9% 1 CIA Factbook; last update 17.05.2011 (applies for all following data) https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html 2 UNDP http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/UGA.html 3 Exchange rate from 18.04.2011 http://www.bankenverband.de/waehrungsrechner/ 1 Table of contents History .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Before colonialism ................................................................................................................................... -

2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003

Uganda Page 1 of 26 Uganda Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003 President Yoweri Museveni continued to dominate the Government after he was reelected to a second 5-year term in March 2001. He has ruled since 1986 through the dominant political party, The Movement. The Constitution provides for an autonomous, independently elected President and a 295-member unicameral Parliament whose members were elected to 5-year terms. The Parliament was weak compared to the Executive, although it occasionally displayed independence and assertiveness. In the June 2001 parliamentary elections, more than 50 percent of those elected were new legislators; however, Movement supporters remained in control of the legislative branch. Observers believed that the 2001 presidential and parliamentary elections generally reflected the will of the population; however, both were marred by serious irregularities, particularly in the period leading up to the elections, such as restrictions on political party activities, incidents of violence, voter intimidation, and fraud. A 2000 national referendum on the role of political parties formally extended the Movement form of government indefinitely and severely restricted political activities. The Constitutional Review Commission (CRC) continued to work to amend the 1995 Constitution during the year. The judiciary generally was independent but was understaffed and weak; the President had extensive legal powers. The Uganda People's Defense Force (UPDF) was the key security force. The Constitution provides for civilian control of the UPDF, with the President designated as Commander in Chief; a civilian served as Minister of Defense. -

Adjusting to Life As a Politician's Spouse Bukenya Rejects Court

New Vision U G A N D A ’ S L E A D I N G D A I L Y Tuesday, June 7, 2011 Vol.26 No.112 Price: USH 1,200200 (KSH(KSHKSKSHSH 80,8080, TZSHTZSH 1,200,1 RF 650) Bukenya rejects Adjusting to life as a court summons politician’s spouse Ex Vice-President accused of abuse of office, p4 Find the tips and much more in HER Vision MUSEVENI WARNS NEW MINISTERS PHOTO BY KENNEDY ORYEMA President Museveni (centre in yellow tie) posing for a photo with the new ministers after they were sworn in at the State House in Entebbe yesterday. See story on P3 and pictures on P5 Seya refuses to Makerere to train 4 UPDF soldiers killed in Somalia surrender house graduates for free By JOSHUA KATO around Bondhere district on Saturday. By ANDREW SSENYONGA By FRANCIS KAGOLO Four UPDF peacekeepers, Tibihwa is the highest including Lt. Col Patrick ranking UPDF officer to be Former Kampala mayor Makerere University has Tibihwa, have been killed killed in Mogadishu. Nasser Sebaggala has invited its graduates who in the volatile Somali capital He hails from Nyamahunza handed over office to the failed to get jobs to go back for Mogadishu. village, Mukunyu sub-county Lord mayor, Erias Lukwago. free vocational training. Tibihwa, who was the in Kasese district. However, Sebaggala vowed The programme, which the commanding officer of the In a statement, army not to vacate the town clerk’s vice-chancellor, Prof. 23 battalion, was hit by a spokesperson Maj. Felix stray bullet as he inspected CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 Sebaggala CONTINUED ON PAGE 3 Prof. -

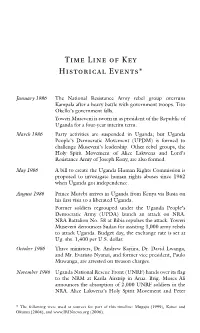

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

Downloads/2014/05/UGMP-Opinion-Poll-Report-May-2014.Pdf

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/127926 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Electoral coalition-building among opposition parties in Zimbabwe, Zambia and Uganda from 2000 to 2017 Nicole Anne Beardsworth Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Politics in the Department of Politics and International Studies (PAIS) at the University of Warwick. June 2018 78 241 words Contents List of Figures and Tables 3 Acknowledgements 5 Declaration and Inclusion of Published Work 7 Abstract 8 Abbreviations 9 1. Introduction 11 1.1 The Puzzle 11 1.1.1 Research Questions 12 1.1.2 Opposition Pre-Electoral Coalitions in Africa 13 1.1.3 The Argument 38 1.2 Design and Methods 42 1.2.1 Case Studies and Process Tracing 42 1.2.2 Case Selection 46 1.2.3 Data 49 1.3 Organisation of the Thesis 57 2. Consistent Coalition Formation in Uganda 59 2.1 Introduction 59 2.1.1 Political Parties and the Logic of Coalition Formation in Uganda 61 2.2 Coalitions Under the Movement System (1996-2005) 76 2.2.1 The 1996 Election and the IPFC Coalition 76 2.2.2 Kizza Besigye and the 2001 Alliance 79 2.3 Multi-Party Coalitions (2006-2016) 82 2.3.1 The 2006 G6 82 2.3.2 The 2011 Inter-Party Cooperation (IPC) 91 2.3.3 The 2016 Democratic Alliance (TDA) Coalition 103 2.4 Constant Coalition Formation, Constant Fragmentation 119 3. -

UGANDA: NOT a LEVEL PLAYING FIELD Government Violations in the Lead-Up to the Election

UGANDA: NOT A LEVEL PLAYING FIELD Government Violations in the Lead-Up to the Election I’m not ready to hand over power to people or groups of people who have no ability to manage a nation ….Why should I sentence Ugandans to suicide by handing over power to people we fought and defeated? It’s dangerous despite the fact that the constitution allows them to run against me…. At times the constitution may not be the best tool to direct us politically for it allows wrong and doubtful people to contest for power. President Yoweri Museveni, addressing a rally in western Uganda. East African, February 12, 2001. I. Summary.............................................................................................................................................2 II. Recommendations ...............................................................................................................................3 To the Ugandan Government:...............................................................................................................3 To the Electoral Commission:...............................................................................................................4 To all Presidential Candidates:..............................................................................................................4 To the International Community: ..........................................................................................................4 To the Commonwealth Secretariat: .......................................................................................................4