Legacy Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

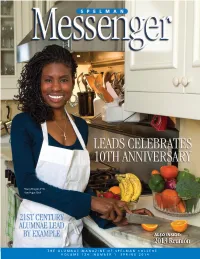

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Working the Democracy: the Long Fight for the Ballot from Ida to Stacey

Social Education 84(4), p. 214–218 ©2020 National Council for the Social Studies Working the Democracy: The Long Fight for the Ballot from Ida to Stacey Jennifer Sdunzik and Chrystal S. Johnson After a 72-year struggle, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted whose interests should be represented, American women the right to vote in 1920. Coupled with the Fifteenth Amendment, and ultimately what policies will be which extended voting rights to African American men, the ratification of the implemented at the local and national Nineteenth Amendment transformed the power and potency of the American electorate. levels. At a quick glance, childhoods par- Yet for those on the periphery—be Given the dearth of Black women’s tially spent in Mississippi might be the they people of color, women, the poor, voices in the historical memory of the only common denominator of these two and working class—the quest to exer- long civil rights struggle, we explore the women, as they were born in drastically cise civic rights through the ballot box stories of two African American women different times and seemed to fight dras- has remained contested to this day. In who harnessed the discourse of democ- tically different battles. Whereas Wells- the late nineteenth century and into the racy and patriotism to argue for equality Barnett is best known for her crusade twentieth, white fear of a new electorate and justice. Both women formed coali- against lynchings in the South and her of formerly enslaved Black men spurred tions that challenged the patriarchal work in documenting the racial vio- public officials to implement policies boundaries limiting who can be elected, lence of the 1890s in publications such that essentially nullified the Fifteenth as Southern Horrors and A Red Record,1 Amendment for African Americans in she was also instrumental in paving the the South. -

Celebrating Black History Month – February 2014

Celebrating Black History Month – February 2014 Black History Month remains an important moment for America to celebrate the achievements and contributions black Americans have played in U.S. history. Arising out of "Negro History Week," which first began in the 1920s, February has since been designated as Black History Month by every U.S. president since 1976. Below is a list of 30 inspirational quotes from some of the most influential black personalities of all time: 1. "Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave. I rise. I rise. I rise." - Maya Angelou 2. "We should emphasize not Negro history, but the Negro in history. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice." - Carter Woodson 3. "Do not call for black power or green power. Call for brain power." - Barbara Jordan 4. "Hate is too great a burden to bear. It injures the hater more than it injures the hated." - Coretta Scott King 5. "Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that." - Martin Luther King, Jr. 6. "I am where I am because of the bridges that I crossed. Sojourner Truth was a bridge. Harriet Tubman was a bridge. Ida B. Wells was a bridge. Madame C. J. Walker was a bridge. Fannie Lou Hamer was a bridge." - Oprah Winfrey 7. "Whatever we believe about ourselves and our ability comes true for us." - Susan L. -

Web Site Brochure.Indd

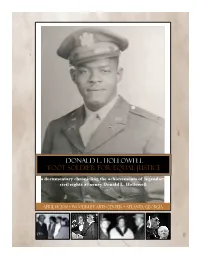

Donald L. Hollowell Foot Soldier for Equal Justice a documentary chronicling the achievements of legendary civil rights attorney Donald L. Hollowell April 15, 2010 * Woodruff Arts Center * Atlanta, Georgia [ Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Esq. Maurice C. Daniels, Dean and Professor Endowment Committee Chairman University of Georgia School of Social Work I finished law school the first I have been a member of the Friday in June 1960. The Monday faculty of the University of morning after I graduated, I went Georgia for more than 25 to work for Donald Hollowell for years. My tenure here was made $35 a week. I was his law clerk possible because of the courage, and researcher, and I carried his commitment, and brilliance of briefcase and I was his right-hand Donald Hollowell. Therefore, I man. He taught me how to be am personally and professionally a lawyer, a leader, how to fight committed to continuing Mr. injustice. Whatever I have become Hollowell’s legacy as a champion in the years, I owe it to him in for the cause of social justice. large measure. — Maurice C. Daniels — Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. Dear Colleagues and Friends, To commemorate and continue the legacy of Donald L. Hollowell, one of our nation’s greatest advocates for social justice, the University of Georgia approved the establishment of the Donald L. Hollowell Professorship of Social Justice and Civil Rights Studies in the School of Social Work. Donald L. Hollowell was the leading civil rights lawyer in Georgia during the 1950s and 1960s. He was the chief architect of the legal work that won the landmark Holmes v. -

Lee & Low Books Dear Mrs. Parks Teacher's Guide P. 1

Lee & Low Books Dear Mrs. Parks Teacher’s Guide p. 1 Classroom Guide for DEAR MRS. PARKS A Dialogue with Today’s Youth by Rosa Parks with Gregory J. Reed Reading Level Interest Level: Grades 1-5 Reading Level: Grades 2-3 (Reading level based on the Spache Readability Formula) Accelerated Reader® Level/Points: 4.7/2.0 Lexile Measure®: 850 Scholastic Reading Counts!™:5.4 Themes: Self-Esteem/Indentity, Civil Rights, Family, History, African Americans, Discrimination, Religion/Spiritual, Nonfiction, Remarkable Women, Young Adult Synopsis In this book Rosa Parks shares some of the many thousands of letters she receives from young people around the world. The letters not only ask about Mrs. Parks’ life and experiences, but they reflect the timeless concerns that youth face about personal and societal issues. In her careful and heartfelt responses, Rosa Parks displays the same authority and dignity she showed the world in 1955 when she refused to give up her seat to a white man on a racially segregated city bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Her message is one of compassion and hope. Says Parks, “It is my prayer that my legacy . will be a source of inspiration and strength to all who receive it.” Dear Mrs. Parks has won many accolades including the NAACP Image Award, Teachers’ Choices Award, Notable Children’s Trade Book in the Field of Social Studies, and Blackboard Book of the Year in Children’s Literature. Background Rosa Parks was born on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Alabama. She made history when in December 1955, she refused to give up her seat to a white Lee & Low Books Dear Mrs. -

Funeral for Dr. Dorothy Irene Height

in thanksgiving for and in celebration of the life of Dr. Dorothy Irene Height march 24, 1912 – april 20, 2010 thursday, april 29, 2010 ten o’clock in the morning the cathedral church of st. peter & st. paul in the city & episcopal diocese of washington carillon prelude Dr. Edward M. Nassor Carillonneur, Washington National Cathedral Swing low, sweet chariot Traditional Spiritual, arr. Milford Myhre Precious Lord, take my hand Take My Hand, Precious Lord, arr. Joanne Droppers I come to the garden alone In the Garden, arr. Sally Slade Warner We shall overcome Traditional Spiritual, arr. M. Myhre O beautiful, for spacious skies Materna, arr. M. Myhre Mine eyes have seen the glory Battle Hymn of the Republic, arr. Leen ‘t Hart Lift every voice and sing Lift Every Voice, arr. Edward M. Nassor organ prelude Jeremy Filsell Artist in Residence, Washington National Cathedral Allegro Risoluto, from Deuxième Symphonie, Op. 20 Louis Vierne (1870–1937) Variations on a shape-note hymn (Wondrous Love), Op. 34 Samuel Barber (1910–1981) Prelude and Fugue in E flat, BWV 552 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14 (transcribed by Nigel Potts) Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943) choral prelude The Howard University Choir Dr. J. Weldon Norris, Conductor Mass in G Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Kyrie Agnus Dei Glory Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) Listen to the Lambs R. Nathaniel Dett (1882–1943) Precious Lord Thomas A. Dorsey (1899–1993) Lord, I don’ Done J. Weldon Norris The people stand, as they are able, at the tolling of the Bourdon Bell. resurrection anthem in procession Dr. -

ECHO-LDPP Wellness Bulletin June 15, 2020 Greetings from Dr. Allison Fuligni What’S Going on with Time?

ECHO-LDPP Wellness Bulletin June 15, 2020 Greetings from Dr. Allison Fuligni What’s going on with time? Have you noticed time seems to be moving in funny ways these days? My last day in the classroom on campus seems like ages ago, but I also find myself thinking “it’s June already?” Days seem to last forever but weeks fly by as we maintain our social distance. When I was in high school, I became enamored with the phrase “time marches on.” It meant to me that I Care and Am Willing to Serve if I was going through a difficult time, there would come © by Marian Wright Edelman a day when it was past and I would be able to look back and recognize that I was not in that tough time anymore. Lord I cannot preach like Martin Luther King, Jr. or turn It also meant that a great day or a precious moment a poetic phrase like Maya Angelou would also not last, and reminded me to make note of it, but I care and am willing to serve. remember it. I do not have Fred Shuttlesworth’s and Harriet More recently, a similar idea emerged as I Tubman’s courage or Franklin Roosevelt’s political skills learned about mindfulness practices. Mindful meditation but I care and am willing to serve. teachers encourage us to be present in this current I cannot sing like Fannie Lou Hamer or organize like Ella moment, not stuck in the past or worrying about the Baker and Bayard Rustin future. -

Sisters of Freedom

SISTERS OF FREEDOM African American Women Moving Us Forward Drawing from its remarkable archive and additional sources, Syracuse Cultural Workers curated this in- spirational and educational exhibit on African American women from the 1800’s to present. While by no means exhaustive, “Sisters of Freedom” provides a dramatic glimpse of the power and passion of 41 women who have transformed their lives, their culture and their country. Ideal for colleges, schools, religious groups, unions, professional organizations, conferences, special events, and many other venues Sisters of Freedom consists of six tri-fold panels (folds down to 3’ x 4’). Lightweight and portable, it is meant to be displayed on six 6’ tables and can be set up in 30 minutes. PANEL A (1 OF 6) PANEL D (4 of 6) PANEL F (6 of 6) *Sojourner Truth, The National Fannie Lou Hamer, Dorothy *Audre Lorde, Homage to Kitch- Women’s History Project, Height, Dorothy Cotton, en Table Press, Barbara Smith, *Harriet Tubman, *Lucy Parsons Marian Wright Edelman, African American Women..., Maya Angelou, Bernice Johnson Anita Hill, Lateefah Simon, PANEL B (2 OF 6) Reagon, *Nina Simone *Ellen Blalock, Cheryl Contee, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, *Sarah Kimberly Freeman Brown, Loguen Fraser, Mary McLeod PANEL E (5 of 6) Majora Carter, Imani Perry Bethune, Zora Neale Hurston, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Unita Pauli Murray, Ella J. Baker Blackwell, Daisy Bates, Gloria *related products available St. Clair Hayes Richardson, Alice see back page PANEL C (3 of 6) Walker, Coretta Scott King, Septima P. Clark, Odetta, *Rosa Angela Davis, Shirley Chisholm, Parks, *Claudette Colvin, 1961 Cynthia McKinney, *Barbara Lee Freedom Riders, Diane Nash SoF Info Guide 5/13 cialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists who were op- SISTERS OF FREEDOM PROFILES posed to the policies of the American Federation of Labor. -

Pauli Murray: Eleanor Roosevelt's Beloved Radical

Pauli Murray: Eleanor Roosevelt's Beloved Radical The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mack, Kenneth W. 2016. Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt's Beloved Radical. Review of "The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice," Patricia Bell-Scott, Boston Review, February 29, 2016. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:38824934 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt's Beloved Radical KENNETH W. MACK BOSTON REVIEW, February 29, 2016 The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice Patricia Bell-Scott Alfred A. Knopf, $30 (cloth) During her long and contentious life that spanned much of the twentieth century, Pauli Murray (1910–1985) involved herself in nearly every progressive cause she could find. Yet the contributions of this black woman writer, activist, civil rights lawyer, feminist theorist, and Episcopal priest have 1 largely escaped public attention. Murray earned a reputation as an idealist who saw the world differently from many of the activists who surrounded her. She also walked away from several important organizations and movements when they were at the height of their influence. At the same time, her actions have seemed prescient to those involved in many of the social movements that have subsequently claimed a piece of her legacy. -

Choosing to Participate and the Re-Release of This Book Which Has Been Developed to Give Educators a Tool to Explore the Role of Citizenship in Democracy

R evised E Praise for dition FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES PUBLICATION C We are well aware of the forces beyond our control—the attitudes, modes of H behavior, and unexamined assumptions that often, sadly, govern the larger OOSING society, and that undermine the school communities we seek to build. It is to this end that we find Facing History so powerful. From both discussions with teachers and observations of student interaction, it is clear that Facing TO History and Ourselves is a tremendously effective vehicle for engaging P ARTICI students in the critical dialogues essential for a tolerant and just society. Dan Isaacs P Former Assistant Superintendent ATE of the Los Angeles Unified School District • A Facing History and Facing History and Ourselves has become a standard for ambitious and CHOOSING TO courageous educational programming…. At a time when more and more of our population is ignorant about history, and when the media challenge PARTICIPA T E the distinction between truth and fiction—indeed, the very existence of REVISED EDITION truth—it is clear that you must continue to be the standard. Howard Gardner O Professor of Education, Harvard Graduate School of Education urselves Publication Teaching kids to fight intolerance and participate responsibly in their world is the most important work we can do. Matt Damon, Actor, Board of Trustees Member & Former Facing History and Ourselves Student Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445 (617) 232-1595 www.facinghistory.com Visit choosingtoparticipate.org for additional resources, inspiring stories, ways to share your story, and a 3D immersive environment of the exhibition for use in the classroom and beyond. -

Celebrating Black History Month and Marian Wright Edelman's Work

Social Studies and the Young Learner 24 (2), pp. 18–22 ©2011 National Council for the Social Studies Young Children as Activists: Celebrating Black History Month and Marian Wright Edelman’s Work Brigitte Emmanuelle Dubois ood schools for everyone!” “Safe homes for kids!” grade levels and became a tradition that students and teachers The righteous and robust voices of 15 five- and six- looked forward to each year. This article details our explora- “G year-olds filled the cold air as we marched across tion of the life of Marian Wright Edelman as it unfolded in a the brick paths of Lafayette Park in Washington, DC, directly kindergarten classroom. across the street from the White House. We were following in the footsteps of generations of activists and demonstrators who Beginnings gathered at this very spot to declare their passionate belief in a Born in South Carolina in 1939, Marian Wright Edelman was cause and to advocate for change. As the line of kindergarteners raised with a firm belief in personal responsibility, service to wound its way around historic statues and monuments, one others, and spiritual faith. At Spelman College, a historically boy exclaimed, “Maybe the president will see us!” All eyes black college in Atlanta, she was a student of the noted pro- turned toward the windows of the White House. President gressive historian Howard Zinn. She came of age in the 1960s Obama’s inauguration had taken place one month before, just and emerged as a young leader in the Civil Rights Movement, two miles away, and the children had absorbed the excitement graduated from Yale Law School, and was the first black woman that gripped the city in the wake of his historic election.