Using Hillary Clinton's Presidential Campaign for Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Working the Democracy: the Long Fight for the Ballot from Ida to Stacey

Social Education 84(4), p. 214–218 ©2020 National Council for the Social Studies Working the Democracy: The Long Fight for the Ballot from Ida to Stacey Jennifer Sdunzik and Chrystal S. Johnson After a 72-year struggle, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted whose interests should be represented, American women the right to vote in 1920. Coupled with the Fifteenth Amendment, and ultimately what policies will be which extended voting rights to African American men, the ratification of the implemented at the local and national Nineteenth Amendment transformed the power and potency of the American electorate. levels. At a quick glance, childhoods par- Yet for those on the periphery—be Given the dearth of Black women’s tially spent in Mississippi might be the they people of color, women, the poor, voices in the historical memory of the only common denominator of these two and working class—the quest to exer- long civil rights struggle, we explore the women, as they were born in drastically cise civic rights through the ballot box stories of two African American women different times and seemed to fight dras- has remained contested to this day. In who harnessed the discourse of democ- tically different battles. Whereas Wells- the late nineteenth century and into the racy and patriotism to argue for equality Barnett is best known for her crusade twentieth, white fear of a new electorate and justice. Both women formed coali- against lynchings in the South and her of formerly enslaved Black men spurred tions that challenged the patriarchal work in documenting the racial vio- public officials to implement policies boundaries limiting who can be elected, lence of the 1890s in publications such that essentially nullified the Fifteenth as Southern Horrors and A Red Record,1 Amendment for African Americans in she was also instrumental in paving the the South. -

The Book Thief

Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection Becoming By Michelle Obama First published in 2018 Genre & subject Biography Michelle Obama President’s spouses Synopsis An intimate, powerful, and inspiring memoir by the former First Lady of the United States In a life filled with meaning and accomplishment, Michelle Obama has emerged as one of the most iconic and compelling women of our era. As First Lady of the United States of America- the first African-American to serve in that role-she helped create the most welcoming and inclusive White House in history, while also establishing herself as a powerful advocate for women and girls in the U.S. and around the world, dramatically changing the ways that families pursue healthier and more active lives, and standing with her husband as he led America through some of its most harrowing moments. Along the way, she showed us a few dance moves, crushed Carpool Karaoke, and raised two down-to-earth daughters under an unforgiving media glare. In her memoir, a work of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Michelle Obama invites readers into her world, chronicling the experiences that have shaped her-from her childhood on the South Side of Chicago to her years as an executive balancing the demands of motherhood and work, to her time spent at the world's most famous address. With unerring honesty and lively wit, she describes her triumphs and her disappointments, both public and private, telling her full story as she has lived it-in her own words and on her own terms. Warm, wise, and revelatory, Becoming is the deeply personal reckoning of a woman of soul and substance who has steadily defied expectations-and whose story inspires us to do the same. -

In the Media, a Woman's Place

Symposium In the Media, A Woman's Place OR WOMEN AND THE MEDIA, 1992 was a year of sometimes painful change-the aftermath of the Anita Hill PClarence Thomas hearings; the public spectacle of a vice presi dent's squabble with a fictional TV character; Hillary Rodham Clinton's attempt to redefine the role of the political wife; election of women to Congress and to state offices in unprecedented numbers. Whether the "Year of the Woman" was just glib media hype or truly represented a sea change for women likely will remain subject to debate for years to come. It is undeniable, however, that questions of gender and media performance became tightly interwoven, perhaps inextricably, in 1992. What do the developments of 1992 portend for media and women? What lessons should the media have learned? What changes can be predicted? We invited 15 women and men from both inside and outside the media for their views on those and related issues affecting the state of the media and women in 1993 and beyond. The result is a kind of sy~posium of praise, warnings and criticism for the press from jour nahsts and news sources alike, reflecting on changes in ' media treat ment of women, and in what changes women themselves have wrought on the press and the society. LINDA ELLERBEE Three women have forced people to rethink their attitudes toward women and, perhaps more importantly, caused women to rethink 49 Symposium-In the Media, A Womans how we see ourselves. Two of those women-Anita Hill and Clinton-are real. -

{Download PDF} the Audacity of Hope Thoughts on Reclaiming The

THE AUDACITY OF HOPE THOUGHTS ON RECLAIMING THE AMERICAN DREAM 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Barack Obama | 9780307455871 | | | | | The Audacity of Hope Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream 1st edition PDF Book About the Book. He fascinated millions of people all The book, divided into nine chapters, outlines Obama's political and spiritual beliefs, as well as his opinions on different aspects of American culture. As you might anticipate from a former civil lawyer and a university lecturer on constitutional law, Obama writes convincingly about race as well as the lofty place the Constitution holds in American life As for his book, however, I found it frilly, subtly self-righteous, and, ironically, pretty mundane. Medicare may not be perfect, but God save us from the US system! More filters. The situation for most blacks and Latinos is still terrible. And he grapples with the role that faith plays in a democracy—where it is vital and where it must never intrude. Barack Obama was the 44th president of the United States, elected in November and holding office for two terms. Read full review. Condition: Very Good. Common ground at its best, on a topic that I usually find utterly alienating. Wow, this man is really going to be our President? This chapter is the reason I docked this book a star. Sampson in Richmond, Virginia , in the late s, on the G. Available From More Booksellers. Some had well-developed theories to explain the loss of manufacturing jobs or the high cost of health care. If two guys were standing on a corner, I would cross the street to hand them campaign literature. -

Celebrating Black History Month – February 2014

Celebrating Black History Month – February 2014 Black History Month remains an important moment for America to celebrate the achievements and contributions black Americans have played in U.S. history. Arising out of "Negro History Week," which first began in the 1920s, February has since been designated as Black History Month by every U.S. president since 1976. Below is a list of 30 inspirational quotes from some of the most influential black personalities of all time: 1. "Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave. I rise. I rise. I rise." - Maya Angelou 2. "We should emphasize not Negro history, but the Negro in history. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice." - Carter Woodson 3. "Do not call for black power or green power. Call for brain power." - Barbara Jordan 4. "Hate is too great a burden to bear. It injures the hater more than it injures the hated." - Coretta Scott King 5. "Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that." - Martin Luther King, Jr. 6. "I am where I am because of the bridges that I crossed. Sojourner Truth was a bridge. Harriet Tubman was a bridge. Ida B. Wells was a bridge. Madame C. J. Walker was a bridge. Fannie Lou Hamer was a bridge." - Oprah Winfrey 7. "Whatever we believe about ourselves and our ability comes true for us." - Susan L. -

Web Site Brochure.Indd

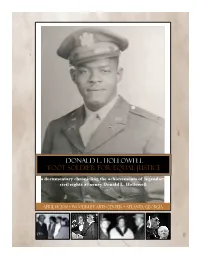

Donald L. Hollowell Foot Soldier for Equal Justice a documentary chronicling the achievements of legendary civil rights attorney Donald L. Hollowell April 15, 2010 * Woodruff Arts Center * Atlanta, Georgia [ Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Esq. Maurice C. Daniels, Dean and Professor Endowment Committee Chairman University of Georgia School of Social Work I finished law school the first I have been a member of the Friday in June 1960. The Monday faculty of the University of morning after I graduated, I went Georgia for more than 25 to work for Donald Hollowell for years. My tenure here was made $35 a week. I was his law clerk possible because of the courage, and researcher, and I carried his commitment, and brilliance of briefcase and I was his right-hand Donald Hollowell. Therefore, I man. He taught me how to be am personally and professionally a lawyer, a leader, how to fight committed to continuing Mr. injustice. Whatever I have become Hollowell’s legacy as a champion in the years, I owe it to him in for the cause of social justice. large measure. — Maurice C. Daniels — Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. Dear Colleagues and Friends, To commemorate and continue the legacy of Donald L. Hollowell, one of our nation’s greatest advocates for social justice, the University of Georgia approved the establishment of the Donald L. Hollowell Professorship of Social Justice and Civil Rights Studies in the School of Social Work. Donald L. Hollowell was the leading civil rights lawyer in Georgia during the 1950s and 1960s. He was the chief architect of the legal work that won the landmark Holmes v. -

Religion and the Arts in America

Religion and the Arts in America CAMILLE PAGLIA At this moment in America, religion and pol- itics are at a flash point. Conservative Christians deplore the left-wing bias of the mainstream media and the saturation of popular culture by sex and violence and are promoting strate- gies such as faith-based home-schooling to protect children from the chaotic moral relativism of a secular society. Liberals in turn condemn the meddling by Christian fundamentalists in politics, notably in regard to abortion and gay civil rights or the Mideast, where biblical assumptions, it is claimed, have shaped us policy. There is vicious mutual recrimination, with believers caricatured as paranoid, apocalyptic crusaders who view America’s global mission as divinely inspired, while lib- erals are portrayed as narcissistic hedonists and godless elit- ists, relics of the unpatriotic, permissive 1960s. A primary arena for the conservative-liberal wars has been the arts. While leading conservative voices defend the tradi- tional Anglo-American literary canon, which has been under challenge and in flux for forty years, American conservatives on the whole, outside of the New Criterion magazine, have shown little interest in the arts, except to promulgate a didac- tic theory of art as moral improvement that was discarded with the Victorian era at the birth of modernism. Liberals, on the other hand, have been too content with the high visibility of the arts in metropolitan centers, which comprise only a fraction of America. Furthermore, liberals have been compla- cent about the viability of secular humanism as a sustaining A lecture delivered on 6 February 2007 as the 2007 Cornerstone Arts Lecture at Colorado College. -

Camille Paglia on Freethought, Feminism, and Iconoclasm Conducted by Timothy J

force. Questions both ancient and new are freethought, particularly the criticism of new freedom, but also by a new severi- being raised—do women think differently religious dogmas, has played in bringing ty. For it will be enforced by the realities of associated life as they are disclosed about increasing equality for women. than men? How relevant are biological to careful and systematic inquiry, and and social determinants? Is equality As Dewey pointed out, in a paper writ- not by a combination of convention and among the sexes possible, and, if so, what ten in 1931, an exhausted legal system with senti- mean? The following arti- mentality. does this really The growing freedom of women can cles detail the current debates being raised hardly have any other outcome than the about these issues in feminist circles. In production of more realistic and more The significance of this new freedom is addition, they show the important role that human morals. It will be marked by a explored in the following pages. • FI Interview Camille Paglia on Freethought, Feminism, and Iconoclasm conducted by Timothy J. Madigan One does not really interview Camille Paglia—author of the best-selling works Sexual Personae; Sex, Art, and American Culture; and Vamps and Tramps—one gives her a forum to express her free-wheeling opinions in machine-gun delivery style on whatever issues she wants to address. What follows is a prime example of what might be called her "in-your-face feminism."—Ens. REE INQUIRY: You're one of the few America. Fpublic intellectuals whose work is FI: In Vamps and Tramps, you state discussed both on college campuses and that "the silencing of authentic debate in working-class bars. -

What Happened Hillary Rodham Clinton This Reading Group Guide

What Happened Hillary Rodham Clinton This reading group guide for What Happened includes an introduction, discussion questions, and ideas for enhancing your book club. The suggested questions are intended to help your reading group find new and interesting angles and topics for your discussion. We hope that these ideas will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book. Introduction Hillary Rodham Clinton is the first woman in US history to become the presidential nominee of a major political party. She served as the 67th Secretary of State—from January 21, 2009, until February 1, 2013 —after nearly four decades in public service advocating on behalf of children and families as an attorney, First Lady, and Senator. She is a wife, mother, and grandmother. In What Happened Hillary Clinton reveals, for the first time, what she was thinking and feeling during one of the most controversial and unpredictable presidential elections in history. Now free from the constraints of running, Hillary takes you inside the intense personal experience of becoming the first woman nominated for president by a major party in an election marked by rage, sexism, exhilarating highs and infuriating lows, stranger-than-fiction twists, Russian interference, and an opponent who broke all the rules. This is her most personal memoir yet. Topics & Questions for Discussion 1. In the Introduction to What Happened, Hillary Clinton begins with this statement: “In the past, for reasons I try to explain, I’ve often felt I had to be careful in public, like I was up on a wire without a net. -

From Here to Queer: Radical Feminism, Postmodernism, and The

From Here to Queer: Radical Feminism, Postmodernism, and the Lesbian Menace (Or, Why Can't a Woman Be More like a Fag?) Author(s): Suzanna Danuta Walters Source: Signs, Vol. 21, No. 4, Feminist Theory and Practice (Summer, 1996), pp. 830-869 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3175026 . Accessed: 24/06/2014 17:21 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 199.79.170.81 on Tue, 24 Jun 2014 17:21:49 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions FromHere to Queer: Radical Feminism,Postmodernism, and the Lesbian Menace (Or, WhyCan't a Woman Be More Like a Fag?) Suzanna Danuta Walters Queer defined (NOT!) A LREADY, IN THIS OPENING, I am treadingon thin ice: how to definethat which exclaims-with postmodern cool-its absoluteundefinability? We maybe here(and we may be queer and not going shopping),but we are certainlynot transparentor easily available to anyone outside the realm of homo cognoscenti.Yet definitions,even of the tentativesort, are importantif we are to push forwardthis new discourseand debate meaningfullyits parameters.